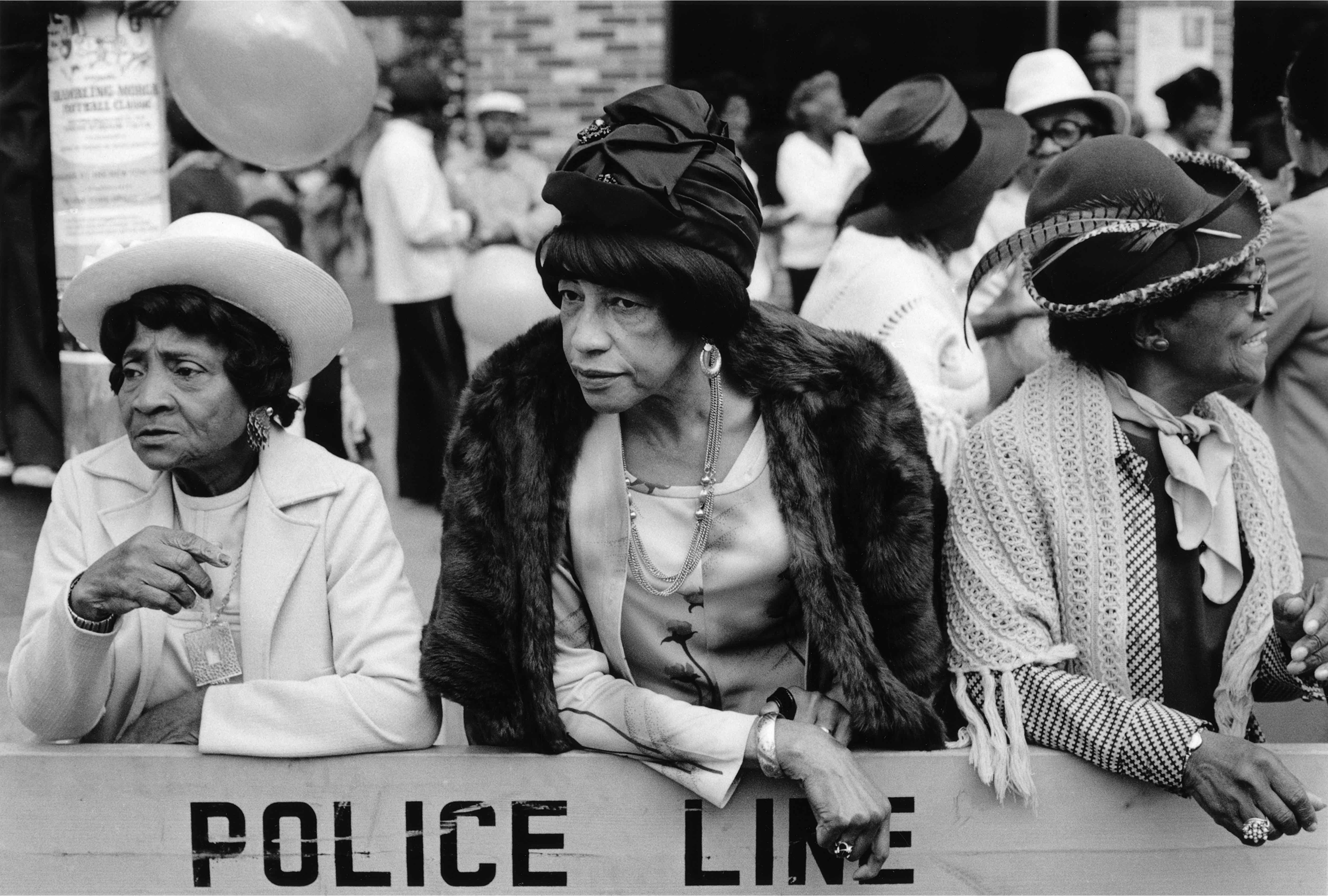

Producing contemporary photography is a delicate negotiation between aesthetic intuition and questions of autonomy. The medium is a chess game of vision and ethics—a game Dawoud Bey seems to have mastered. The Chicago-based photographer, originally from Queens, New York, was a 2017 recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship award (colloquially known as a “Genius Grant”) for his prolific body of portraits of the black community. Spanning back to his now-iconic series Harlem USA (1975-1979), Bey’s images of black life are noted for their commitment to illuminating a multitude of subjective truths behind a complex web of sociopolitical narratives that have dominated the study of black photography from the civil rights era onward.

It’s common for talented photographers to be praised for their ability to see and reveal the souls of their subjects. Multilayered interior states and lived experiences are palpable within the composition of Bey’s images: They’re captivating. But Bey is clear that the camera is a not a tool of metaphysics—it has limitations and biases, and can be used as an accomplice to questionable power dynamics for photographers who neglect to actively subvert that potential. Bey’s mode of subversion is primarily one of principled collaboration. Through his every interaction with individual subjects and broader communities, the images he constructs are uniquely attentive to the weight of specificity. They tell stories, but not ones concerned with tidiness. Their power lies in narrative left lingering—thoughts of what remains outside the frame.

On the occasion of the release of a career-spanning book of his work, Seeing Deeply, Bey reflects on the nuances of his practice and the stakes that underpin the resulting photographs.

“Woman at a Luncheonette,” New York, NY, 1980

Did you think up the title of the book? I’d love to hear about the methodology of “seeing deeply” within your work.

Yes, the title is mine. It’s what I try to do in each project and each individual photograph: to both see the physical surface, but to always look more deeply, to see more than what the mere surface reveals. With the individual, that means to see beyond the social context in which they are situated and to get at that deeper and more complex psychological representation that connects all of us as human beings, trying to find and secure our place in the world, wherever that may be.

A camera as a mechanical and optical device can only visualize the surface. As the artist making the work, it’s incumbent upon me to establish a relationship with the subject that is based on trust, and that then allows the interior person to momentarily come to the surface. “Seeing deeply” to me implies not just describing the obvious surface, but to somehow see and think more deeply about what one is seeing.

I want to borrow what was perhaps a rhetorical question from art historian Sarah Lewis, who contributed a lovely essay to the monograph. “When is the negotiation of being seen in front of the lens a civic act?” Can you speak to the way in which you feel making images of black bodies is inherently political?

“I want to create an expansive representation of the black subject one person at a time, and to have that add up to a broader statement about the fundamental humanity of black people.”

Well, being black is an inherently political state, so the making of representations of the black subject takes place inside of that politicized context. For me, what is important is to give each person a sense of individual presence and psychological nuance—not to consider them as sociological “types,” which often happens in the discourse around the black subject. I want to create an expansive representation of the black subject one person at a time, and to have that add up to a broader statement about the fundamental humanity of black people. And I want to add something to the long history of how black people have been visualized within the medium of photography.

You’ve named various projects after their sites (Harlem USA, The Birmingham Project, etc). Maybe that’s just meant to be practical, but I think it’s also somewhat romantic. Can you speak to the immense presence “site” plays as an additional subject in your work?

When I do an extended project about a place—a particular site—it is an examination of that particular place, whether that is the landscape of the place, its history, or the people who inhabit it. The project titles give the work a specificity: that it is about this place and time.

“A Young Woman and a Girl,” Amityville, NY, 1988

I hear you have roots as a musician. Does an appreciation for melody and rhythm influence the way you take photographs? I imagine a sort of informal choreography goes into making images in a public space.

I began my creative and expressive life as a drummer. I think what I take from that background, having studied and played jazz, is the confidence of being able to go into a situation and freely improvise—to feel comfortable not knowing, but having the understanding of the form you are working inside of, and the full confidence of knowing your instrument, or camera, to such an extent that you can work with it without having to think about it too consciously.

And there’s also the sense of understanding what coherent and resonant form is. In music there’s a certain number of bars, a time signature, the interplay of melody and rhythm. With the photograph there’s the rectangular space of the picture and the opticality of the lens, and how one manipulates that. Being completely fluid with one’s tools allows you to say and do what you need to do freely when you’re in the place where you are making your work.

“Being able to give the black subjects that I was photographing a print was important to me in being able to disrupt the hierarchy of privilege that traditionally exists when only the photographer is in possession of someone’s image.”

Many of the images in the book were shot with a 35mm camera. Although, of course, your choice of equipment will frequently be situational, what’s your favorite set-up? What influenced your foray into Polaroids?

Over the forty-plus years that I’ve been making photographs, I’ve used a range of different cameras, depending on the kind of photographs I was making. Early on I used a 35mm camera with a 35mm lens. It conforms more to the field of vision of the human eye. I stopped using the 35mm camera in the late 1980s and began working with a 4×5 camera on a tripod. Portraits made with a large-format camera are more deliberate, and also require the active consent of the subject, since it’s a much slower process—unlike working with the small handheld 35mm camera, which allows one to work more quickly and, if needed, unobtrusively.

Along with the 4×5 camera, I started using Polaroid film, putting a Polaroid back on the camera and using a film that produced both an instant print and an instant reusable negative. I would give the subjects the instant print and later make exhibition prints from the negatives. Being able to give the black subjects that I was photographing a print was important to me in being able to disrupt the hierarchy of privilege that traditionally exists when only the photographer is in possession of someone’s image, as they were able to immediately confirm the way in which they were being seen and represented.

“A Couple,” New York, NY, 1980

We are in a moment, much like that of the civil rights era, where we see a proliferation of images of black life that largely revolve around the state of American politics and protest. While these images are important in their own right, I find myself more and more coveting images of black joy. Is it important to you to capture joy in your work?

What I covet is black complexity. I want the subjects in my work to exist in a rich psychological space that is more complex than joy or a set of various pathologies or sociology; a complex humanity that belongs to the black subject as much as anyone else. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 9. You can subscribe to the magazine here.