Seen alongside her famously controversial family portraits in the Getty Museum’s A Thousand Crossings retrospective, Sally Mann’s landscapes feel at first almost disappointing in their comparative banality—or, alternately, their experimental imprecision. But if they lack the arresting, at times carnal intimacy of the Immediate Family series, they offer a different, more challenging form of insight into Mann’s personal history and its inseparability from the wider history of the American South. Paradoxically, as Mann opens herself up, she becomes increasingly harder to read, buried beneath layers of constructed narrative and memory; still, gratification is available to those willing to follow on her journey through paradise and back.

Shot in beautiful large format black and white throughout the ’80s and early ’90s, Immediate Family was Mann’s ode to her three children, capturing with calculating precision—often through painstakingly staged reconstructions—various incarnations of their youthful innocence and experience at the family home in rural Virginia. In “Gorjus” (1989), Mann’s older daughter Jessie applies makeup to the younger, Virginia, the two barefoot next to a beat up truck, the feminine act conspicuously incongruous with their ages (eight and four) and distinctly wild surroundings. Various beauty trappings (mirror, hairbrush, makeup pallet) are strewn artfully at their feet. “Easter Dress” (1986) has, even more, the feel of a tableau, with Jessie showing off a new white dress as various figures move in perfect formation around her—a “carefully staged” scene requiring numerous retakes, according to Mann. By contrast, a rare color work like “Bloody Nose” (1991), which shows her son Emmett coated in a shock of red blood from nose to torso, is a simple matter of having been in the right place at the right moment to capture a natural childhood occurrence, at once ordinary and alarmingly visceral.

“Easter Dress,” 1986

Part tribute to the romanticism of the rural idyll as a backdrop to childhood, part testament to the premature parental projection of maturity and its accompanying dangers, the series encapsulates contradictory impulses to control and protect one’s offspring while also letting them learn from experience; to stop time while accepting the inevitability of its passage. The works expressed, too, another unspoken presence: “Even though I take pictures of my children, they’re still about here,” Mann has said, referring to the area around Lexington, Virginia where both she and her children grew up. “The slow, wet air of southern Virginia in July and August exerts a hold on me that I can’t define.”

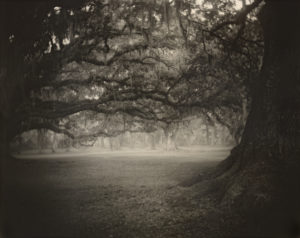

The languid rivers and dense marshlands and trees draped thick with Spanish moss are all illuminated by what Mann reverently called “the radical light of the American South.”

That irrevocable “hold” of the original “here” explains, in part, Mann’s sense—following the publication of Immediate Family—of being “ambushed by [her] backgrounds” when she tried to return to her earlier work. These backgrounds consisted of the Southern landscapes that had surrounded her for the vast majority of her life, the languid rivers and dense marshlands and trees draped thick with Spanish moss, all illuminated by what she reverently called “the radical light of the American South.” And there were other “backgrounds,” too, that rose to the fore of her consciousness as she began to move away from her characteristic portraits (or as she would say, they began to move away from her): in particular, the skeletons beneath the surrounding landscapes belying ugly regional histories, her own family’s Southern roots, her relationship with her husband, and her relationship with herself—all background elements in her earlier works, either present at the peripheries or so deeply embedded as to be near-invisible. Out of each of these elements were born new, concurrent, and more conceptually permeable series, collectively expanding Mann’s existing definition of the “family picture” and the artistic style associated with it.

“Bloody Nose,” 1991

A room at the Getty titled “Family”—which, by Mann’s definition, might apply to any of the other rooms, as well—opens the Getty’s A Thousand Crossings exhibition, combining a selection of familiar works from the Immediate Family series with a number of never-been-seen prints, each more luminous and allegorical than the last. With the works’ narrow intensity, it seems only natural that Mann’s long-term self-exploration through the rich domain of motherhood would inevitably evolve as her primary subjects were in the process of leaving childhood behind, leaving in its stead a compulsion to self-define on new terms. Nevertheless, the difficulty of dissociating her from these famed early works at first presents something of a challenge for viewers approaching the quieter, less recognizable series that make up her later work and the next four rooms of the exhibition.

Seen in the context of the Immediate Family work—as they perhaps inevitably always will be—Mann’s other featured series all have, to an extent, the feel of backgrounds. Many exchange punctum for process, their subjects obscured, indistinct. Though quietly powerful in their own right, the works give pause for their positioning within the show as follow-ups to Immediate Family, and their comparative lack of immediacy when set against those formally and tonally exquisite black and white quasi-documentary works. (There are a handful of lesser-known color works also included in the first section of the exhibition, including “Bloody Nose,” but for all their startling vividness, they struggle to compete.) “It’s not that they are easy, to take or look at,” Mann admitted of her landscapes in a 1994 letter to the now-editor-in-chief of Aperture, “Compared to the family pictures, which had the natural magnetism of portraiture, these are uncompelling.”

“The Turn,” 2005

Yet these works could afford to be uncompelling, precisely because of how compelling the family pictures already were. By enacting a dramatic shift in style from Immediate Family, a near-complete recasting of her aesthetic—if not conceptual—identity, while insisting upon there being continuity between the different series, Mann demands an unexpectedly active role on the part of the viewer. Across her experimental works on Civil War battlefields and more conventional images of other Southern landscapes throbbing with obscured significance, one zealously seeks Mann’s familiar interplay of pastoral purity and lurking danger, sensuous grace and untethered grotesqueness, held in perfect tension by immaculate formal control. If these qualities are absent, one is inclined to project them anyway. For better and worse, Mann is defined by her early work, and has consciously positioned it as a backdrop to her subsequent series, where in the absence of strong formal elements, anything can take on symbolic status.

In her 1998 series tracking sites in Mississippi related to Emmett Till’s murder—reportedly a preoccupation of hers since childhood—there is almost eerily little to see, and certainly no visual markers of the brutality carried out in the name of civilian justice.

In her 1998 series tracking sites in Mississippi related to Emmett Till’s murder—reportedly a preoccupation of hers since childhood—there is almost eerily little to see, and certainly no visual markers of the brutality carried out in the name of civilian justice. The photographs themselves reject traditional rules of aesthetics, often neglecting to offer a distinct focal point or sense of formal balance. The Bridge on Tallahatchie from which Till’s body was said to have been thrown, seen in “Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie),” is painfully nondescript, while the natural world appears to be in the process of discreetly swallowing it whole. Nature here is not inherently menacing, but the viewer’s knowledge of the significance of the scene makes it so; a rogue branch in the foreground becomes an ominous, claw-like hand, invading the middle of the frame as if attempting to further obscure the subject matter behind it. If many of the South’s increasingly contentious historical monuments remain points of local pride, then the anti-monumentality of these landscapes might be seen as offering a channel for the acknowledgment of guilt or regret. Mann contends with her own accountability at both a personal and historical level in this way, with the photographic medium offering a meeting point between the two for exploring past wrongs. Her images are haunted by historical moments of such magnitude as The Battle of Antietam and the lynching of Emmett Till, and those as small but potent as the unspoken “rules” her much-loved black nanny Virginia (Gee-Gee) was forced to contend with while Mann was growing up, like eating her meals in the car when traveling with the family; or the danger a young Mann once subjected a local black man to by unthinkingly offering him a ride home.

“Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie),” 1998

There is a certain irony to the mute unyieldingness of Mann’s work on Till, given that the his 1955 murder became a catalyst for the civil rights movement precisely because of its visibility: the public was notably shaken by the published images of his mutilated body and the open casket funeral, during which his deliberately un-embalmed body was displayed for four days. Other discreet undercurrents from Mann’s family pictures also run through these works, particularly her interest in youth and the boundaries of childhood; that the fourteen-year-old Till was lynched for allegedly flirting with a white woman in her family’s shop fits with Mann’s earlier exploration of the shadow of adult desire and awareness lurking within the contours of childhood, particularly in adults’ premature projection of adulthood onto children, with all its accompanying uncertainties and responsibilities. In this way, Mann’s family portraits become a useful backdrop against which to examine the problematic and ongoing sexualization and adultification of black youth.

In Mann’s series on her husband Larry, she tenderly traces the contours of his body, both before and following his diagnosis of muscular dystrophy.

Aware of her delicate position in relaying these uncomfortable histories, Mann never tries to claim undue authority in her role of observer. Her series Men (2006-2015) is comprised of portraits of black men, their identifying features hazily obscured through visual layering or fragmented into component parts, as if to acknowledge the distance of their own lived experiences from hers, the partiality of her understanding. In her memoir Hold Still, Mann describes having “always seen, but not seen, black men on the fringes of white life”; here she visualizes the limits of her understanding with another “background” being brought to the fore. Stylistically, these works are not unlike Mann’s series on her husband Larry, Proud Flesh, in which she tenderly traces the contours of his body, both before and following his diagnosis of muscular dystrophy. In both these series, she employs the same wet-plate collodion process used for her landscapes, yielding unpredictable results: imperfections in the images’ surface, pockmarks, stains. Her aim with Proud Flesh was not to explicitly represent the effects of the disease on Larry, but particular angles and accidents of process reveal both literal and symbolic glimpses to heartbreaking effect. There is suffering and degeneration that we can see, she seems to be saying, and that which we cannot; she is only there to record, so we must read the cracks in the surface ourselves.

“Hephaestus,” 2008

In Mann’s series Last Measure, capturing the sites of various Civil War battlefields, the distortions produced by her unconventional process are key to disrupting the possibility of a complacent reading of the images. This process involved shooting wet-collodion with an assortment of mismatched antique lenses, essentially employing the same technology that had been used in the mid-nineteenth century to actually document the Civil War, the first major conflict to be photographed extensively. Collodion, moreover, was used to bind wounds during the war; in this way, materiality and history collide, all the more through Mann’s coating of particular images with a hand-made varnish composed of diatomaceous earth from the sites pictured. Landscapes that would otherwise reveal no trace of their bloody pasts take on an air of the uncanny, suggesting a dark history calcified beneath layers of time and willful forgetting. Mann’s images of the site of the Battle of Antietam, the deadliest single day of fighting in all of American history, have a roiling, post-apocalyptic feel; in “Battlefields, Antietam (Black Sun),” a swollen black sun sets within a crumpled sky, while the warping effects of the lens in “Battlefields, Antietam (Trenches)” make the ground appear to be undulating, as though the tens of thousands of dead were at last rallying to the surface.

“Battle Fields, Antietam (Trenches),” 2001

Even those works with a distinctly traditional aesthetic offer their own quiet commentary. Images from her series The Land, like “On the Maury,” recall the Survey photography of the nineteenth century conducted by figures like Muybridge and O’Sullivan; but while they were engaged in a type of anticipatory territorial conquest of as-yet untouched land, Mann is practically doing the inverse—impelling viewers to project the unseen consequences of such past conquests onto deceptively serene landscapes. Throughout, the violent, half-acknowledged history of the South burns beneath the surface of hazy, humid landscapes, just as sexuality and self-consciousness simmers in the lithe, naked bodies and unflinching stares of Mann’s children.

Throughout the show, the timeless collides with the time-bound, as the South’s denial of time’s passage is presented against Mann’s own acceptance of time as a two-edged harbinger of personal growth and degeneration. The dreamy languor of works like “Deep South, Untitled (Fontainebleau),” with its dripping Spanish moss, come into unexpected correspondence with the equally timeless African American subjects of Men, whose shadowy presences continue to haunt the peripheries of the unpeopled landscapes. Underlying the historical themes of the exhibition is a fundamental tension between what we can control and what we cannot—in the face of mortality and loss, historical and personal wrongdoings, past ignorance, and time itself, experiments in form and method open up new possibilities for truth-telling. Accident and uncertainty are permitted, even embraced.

“Deep South, Untitled (Fontainebleau),” negative 1998; print 2017

The last room of the exhibition, titled “What Remains,” offers Mann’s experiments in form applied to herself and her family: a rare body of self-portraits taken while recovering from a riding accident are seen alongside the aforementioned works on her husband and a set of recent portraits of her children, this last group jarringly close-cropped and disambiguated, reminiscent of Victorian death photography (by coincidence, her son Emmett is pictured here in one of the last photos taken of him before his tragic death in 2006). Allowing more raw, private, artistically unconstrained incarnations of her own love and pain and fear to be made public, Mann relinquishes control over these most intimate aspects of her personal and professional life, and lets herself be looked at, too.

There is something almost Wordsworthian about Mann’s self-conscious straddling of the realms of innocence and experience coupled with her profound reverence for the natural world. As though a tribute to Mann’s Immediate Family work, all set in the eternal summer of her children’s youth, Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” begins:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore;—

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day.

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

Indeed, from the start, the purity of her vision is compromised by a foreknowledge of time’s undoings, the Immediate Family photographs like a fairytale depiction of an enchantment fated in due time to be lifted. A desire for control infuses these works, seen in Mann’s notoriously fastidious staging and re-staging of many of the scenes pictured; despite their candid feel, the images were often highly orchestrated, whether to perfectly recreate a moment past, or to enact a particular symbolic ritual or rehearsal for adulthood dreamt up by Mann. Yet by the time she arrives at the later series pictured in the room “What Remains,” her practice has evolved to align with Wordsworth’s sentiments in the Ode’s final stanza, empowered acceptance of the loss that accompanies knowledge:

What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now for ever taken from my sight,

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind

“Triptych,” 2004

Having artistically plumbed the realm of innocence—not only her children’s, but her own naiveté—and come out the other side of personal suffering and historical reckoning, Mann harnesses a new strength drawn not from that which has been lost but “what remains behind.” Personal loss, she finds, can be understood and represented, even depersonalized, through a larger historical conception and acceptance of loss as a permanent state: speaking as a Southerner, Mann states, “Our history of defeat and loss sets us apart from other Americans and because of that we embrace the Proustian concept that the only true paradise is a lost paradise.” The whole show might be seen as an elegy to life’s countless lost paradises; new experiences perpetually reveal old naiveties. Yet rather than lament paradise lost, at each stage, Mann resolutely seeks a new one born of knowledge.

Personal loss, Mann finds, can be understood and represented, even depersonalized, through a larger historical conception and acceptance of loss as a permanent state.

Though nowadays it is widely celebrated as one of the great photography books of our time, Immediate Family and the moral furor surrounding its original publication left Mann with a steadfast reputation as “the photographer who takes pictures of her children nude.” By setting this series against her later projects, many of which Mann claims were developed simultaneously “as an extension of the family pictures” rather than as a replacement, the Thousand Crossings retrospective brings profound new depth to those well-known family portraits, and in so doing, to Mann’s established artistic identity. In this wider context, the backgrounds of these early portraits swell with subtle meaning, as the different series come to feel like so many layers of the same body of work.

History folds in on itself; Emmett Till’s unhappy fate has an echo in that of Emmett Mann, Mann’s son so-named for the former figure, while two generations of Virginias, Mann’s black nanny and youngest daughter, come together in the American state of the same name, also Mann’s birthplace and longtime home. Mann is not only cast as mother, but child, historian, woman. Unyielding Civil War battlefields are made to speak through the use of Civil War-era photographic technology; is it experience or is it innocence-cum-ignorance that seems to reveal itself in the mutilated surfaces of the images? Just as innocence in retrospect might reveal itself to be as ugly as the oft-rued post-paradisal experience, so experience might be imbued with its own less radiant purity. Here, at last, Mann’s radical reconception of the family picture is presented as a kaleidoscopic study of her equally expansive identity and “philosophical mind,” all the wiser and more compassionate for its mortal awareness. As Wordsworth writes, “I love the Brooks which down their channels fret, / Even more than when I tripped lightly as they.” FL