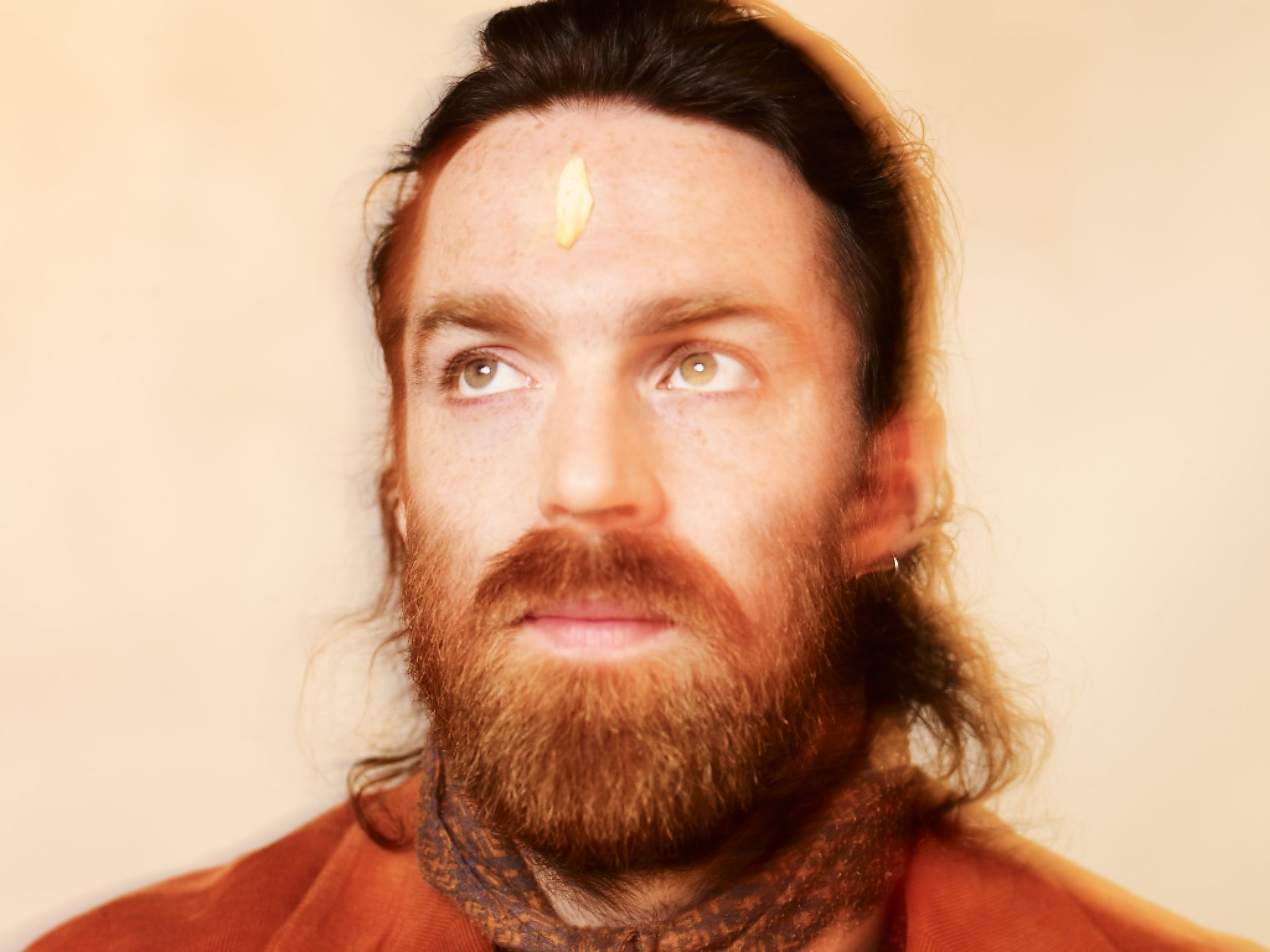

Casual observation of Nick Murphy would peg him as an introvert. The artist formerly known as Chet Faker doesn’t interact or make eye contact with the intimate audience he is playing to during a private rooftop performance at Los Angeles’ NeueHouse. Any banter, as it were, is little more than a mumble. His attire looks like he might have picked it off his bedroom floor, where it lies because it didn’t quite make it to the hamper.

But then, the next day, you realize you’ve got the thirty-year-old Australian expatriate all wrong. There is no introduction to a conversation with him, as Murphy is so loose and comfortable he’s already mid-chat. He is charming, offering a selection of fresh-pressed juices from his shoulder cooler bag. He speaks openly, jumping from topic to topic so fast, he doesn’t always finish what he starts. He smiles so much the freckles on his cheeks threaten to spill into his eyes.

And then Murphy bursts his own bubble by saying, “I was introverted to begin with, and once I realized that I was a musician and this was my life, I developed this shell reaction. Touring all the time brought these really unhealthy inward tendencies.”

As Chet Faker, Murphy’s 2014 album Built on Glass was a stratospheric success, helped along by the super-sexy, can’t-look-away roller-skating video for “Gold.” It wasn’t until 2017 that he released his first music as Nick Murphy, his most self-identifying work—the flawless but criminally overlooked Missing Link EP.

Despite collaborations with fellow countryman Flume and DFA Records’ Marcus Marr, Murphy is a solo operator when it comes to his music. That is, until recently, with his second full-length, Run Fast Sleep Naked. Still, when he started working on the album, it was just him on his own. He traveled to far-flung spots around the globe, choosing his destinations on intuition. He went a little mental in the Northern Sahara Desert in Morocco and spent time with Buddhist monks in temples of Koyasan, Japan. He recorded the vocals for Run Fast Sleep Naked on these trips, then came back to his adopted hometown of New York City and locked himself away in his home studio, keeping dating, romance, and intimacy at bay. Instead, he read about the artistic process in writings by Joseph Campbell, Wassily Kandinsky, Robert Henri, and wrote poetry.

“Campbell calls artists mythmakers, and Kandinsky calls them the spiritual guides of the masses,” says Murphy. “Being an artist is about documenting a spiritual path and being honest and raw with yourself. For me, music has always been about catharsis and honesty, clearing and creating a pathway to growing and moving forward and living a better life. This record embodies that whole journey to me.”

Piano is Murphy’s first instrument, the one he plays for hours without thinking, the one that helps him heal when he feels otherwise debilitated. He moved toward the guitar in his songwriting, mainly for practical purposes—it’s more portable. “The more guitar I play, the more I focus on lyrics,” he says. “With keys, it’s melody and harmony and the sound of the voice with the notes I hit. With guitar, because I strum, I can think more, so I’m telling more of a story.”

“For the last couple of years, I’ve been trying to have more women on the crew because that changes the whole energy … If you leave men alone, they just crumble into a burping and farting abyss.”

He tells stories like “Harry Takes Drugs on the Weekend” and “Novocaine and Coca Cola,” interesting choices for a guy who is approaching nine years of sobriety. The rawness of these tales is biographical, laying his personal experiences bare. The subject of mental state comes up more than once, including on the upbeat “Sanity,” which was written at Rick Rubin’s Shangri-La studio. Despite Murphy’s withdrawals from human contact, much of Run Fast Sleep Naked is about making connections, as illustrated on the aforementioned “Sanity,” and the intimate “Message You at Midnight.”

While Murphy is better known for his music than his paintings or photographs, he expresses himself through various mediums. He puts together sounds compositionally the way he would put together a painting. One of the requests for his tour rider is ink, so he can paint backstage. Another is fresh, local flowers. Most recently, he has been draping wool knits over the gear on stage.

“The stage is so harsh, I’m trying to make it softer,” he explains. “Spending so much time inside buses and not around nature, it’s really nice to smell a rose after you get off a plane or a bus and walk into a venue that smells like beer and piss. I’m on this mission to lessen the severity of touring. For the last couple of years, I’ve been trying to have more women on the crew because that changes the whole energy. Feminine energy goes missing on tour. If you leave men alone, they just crumble into a burping and farting abyss. Touring is a pressure cooker of social intricacies.”

Having ink on hand serves more than one purpose, as all Murphy’s creative expressions inform each other. Painting and photography used to be an escape from music for him. When his music took off, he shut down the other creative parts of himself, thinking he should be focused on one medium. It is only in the last year that he has returned to them. And they, in turn, have amped up his musical output.

Says Murphy, “It was a big lesson for me: just focusing on one thing can not only slow that one thing down, but all things down. You have to be open, and if you feel like drawing, you have to draw, even if you think you should be writing a hit song. This movement happening for me right now is about embracing any form of expression, whether or not it’s viable commercially.”

Not dissimilarly, Murphy opened himself up to people, allowing at least two peers to get involved with Run Fast Sleep Naked. This initially came out of sheer loneliness, after shutting himself away for so long. He reached out to Dave Harrington of Darkside, just to have someone to talk to about music. Harrington’s neo-jazz leanings and esoteric spirituality brought a new way of thinking to Murphy. For the first time, he was able to let go of trying to force a song to become what he wanted it to be, and let it be want it wanted to.

“It was a big lesson for me: just focusing on one thing can not only slow that one thing down, but all things down. You have to be open, and if you feel like drawing, you have to draw, even if you think you should be writing a hit song.”

Also for the first time, Murphy took the recording out of the home studio into Figure 8 Recording in Brooklyn, where he could get sonic space for his sound. Here, they hit the jackpot with engineer Phil Weinrobe. He and Harrington were able to pull out of Murphy what he needed to express.

“They’d look at me and say, ‘What are you trying to say? What are you trying to do?’” remembers Murphy. “I had no idea how to answer. It had always been in my head. I never had to say what I needed. Through learning that, I learned about myself. This amazing trust developed between us, which allowed me to relax into more vulnerable places, because I had people there to catch me. It wasn’t this self-damaging path I would be on if I were on my own.”

At the same time that Murphy had to verbalize where he was trying to go with his songs, he also had to get abstract and let them go, which he says is the most challenging and rewarding thing he’s done in music creation. This allowed him to show his insides on “Yeah I Care”—even if they’re surrounded by barbed rhythms that protect the true sentiments of the song—and on “Hear It Now,” where he speaks about his bleeding heart, an aspect of his persona to which he has reconciled himself.

“I moved to New York because I liked how aggressive it is,” he says. “I had hoped it would pull me out of my shell. I wanted to toughen up a little. It was a silly exercise because I am sensitive. That’s just who I am. It’s not something I need to fix.” FL