This article appears in FLOOD 10. You can purchase the magazine here.

Philippe Cousteau Jr. and Michael Muller have known each other for years, first crossing paths when their nautical passions coincided: Emmy-nominated TV host and producer Cousteau and renowned undersea photographer Muller both spend a majority of their time in the ocean, and when forced to walk on land they’re attempting to educate new generations about environmental conservation and stir cranky adults into long-delayed action.

Initially famed for his intimate portraits of elite actors, musicians, and athletes, Muller fell in love with sharks (a creature he was previously terrified of) and began building a portfolio of underwater shark photography—gorgeous and ferocious in equal measure—with the intent of dispelling preconceived notions about how dangerous the animals are and aiding in shark protection. Cousteau is the grandson of none other than Jacques-Yves Cousteau, co-inventor of the Aqua-Lung and of modern scuba diving, and Philippe carries on Jacques’ legacy with fervor: Along with his wife and collaborator Ashlan, he stars on Travel Channel’s Caribbean Pirate Treasure, a series in which the pair uncover maritime mysteries like pirates and lost treasure; he’s the host of Fox/Hulu syndicated series Xploration Awesome Planet, another earth science exploration of our planet; and he additionally leads EarthEcho International, a foundation dedicated to the education of youth in regard to environmental challenges and solutions.

Both Muller and Cousteau have made recent forays into virtual reality—Cousteau with a new film that premiered at Tribeca, focused on the plastic pollution crisis plaguing our oceans, and Muller with a multi-part series of VR films to be released soon, featuring all manner of undersea creatures filmed all over the globe. Both are terrifically excited about the birth of this new medium, one they hope can inspire people to care about climate change, man-made contamination, and the health and safety of a secret blue world that for so long has remained unknown, but can now be experienced up-close.

So how exactly do you know each other?

So how exactly do you know each other?

Michael Muller: My wife Kimberly and I made a book—well, my wife did, and I supplied the photos—called Last Night I Swam with a Mermaid. She wanted to find an organization to partner with that focused on education and kids, and we found Philippe’s group, EarthEcho. I obviously knew who he was, and had huge respect for his family heritage.

Philippe Cousteau: Yeah, we had drinks at the Chateau Marmont with my wife Ashlan. It was love at first sight. Then we started scheming and dreaming all sorts of things.

Philippe, tell us about your new project, Drop in the Ocean.

Cousteau: Ashlan and I are co-narrators and co-producers on this virtual reality experience, which just premiered at Tribeca Immersive. We asked the question: How can you allow people to experience a critical part of the ocean, but a part that most people don’t even know about—and certainly few, if any, have ever seen? That’s microplankton and plankton. Just to see both phytoplankton and zooplankton, which form the basis of oceanic food chains, and then also provide the majority of our oxygen on earth…arguably, that’s pretty critical. Two out of every three breaths is generated by phytoplankton in the ocean. It doesn’t come from the rainforest—there is a lot of oxygen contributed by that, but the majority of our oxygen comes from the ocean. We wanted to find a way to expose people to that world.

“By the middle of this century, we could have more plastic by volume than animals in the ocean. What do you define an area that is mostly trash as? A dump.” — Philippe Cousteau Jr.

That’s what is wonderful about VR—it gives you an immersive experience. It’s designed in a curated space, and you’re shrunk down to about the size of a thumb, then you float through the ocean. As you slowly ascend up toward the surface, you’re startled to see all of these things floating there—plastics and microplastics. People are familiar with buoys and nets and flip-flops and straws and all these other things that we see on television. But they don’t biodegrade. They photodegrade, so with exposure to sunlight, they break up into small pieces that never go away.

One of the things that we are able to see through Drop in the Ocean, by shrinking people down to this size, is the microplastics that are now insidious and permeate every square kilometer of oceans on earth. Those microplastics are getting into the food chain, because small planktonic animals mistake them for food, in the same way that seabirds have been known to swallow bottle caps. They are bioaccumulating as they work their way up the food chain, as the larger plankton eat the smaller bits of microplastic, then the even larger plankton eat those, and the fish eat those, on and on until it gets to human beings. There’s a real concern that by the middle of this century, we could have more plastic by volume than animals in the ocean. What do you define an area that is mostly trash as? A dump.

Ashlan and Philippe Cousteau Jr. / photo courtesy of Voyacy Ventures

What is it about a VR experience, specifically, that you think might make people care more about the ocean?

Muller: The majority of people don’t go scuba diving. They’ll see it on TV, Blue Planet or whatever, and there’s obviously a lot of people that dive, but even divers don’t necessarily see great white sharks and whales. Watching it on a one-dimensional plane on a TV…it’s just completely different when you put on a headset. I’ve been with very high net-worth individuals in the middle of a restaurant in their three-piece suits, and they put the VR goggles on, and they try to reach out and touch the whale swimming by. You’re like, “Dude, you’re in a restaurant.” But they forget.

To give people that experience—like they’re actually swimming or becoming plankton— is great for empathy. It’s a really powerful tool. Especially for this next generation—I know Philippe is in the same boat I’m in, which is that I don’t put a lot of worth on what we’re doing. It’s this next generation that is inheriting the dump. My goal is to inspire, to get that one kid who sees it, to plant the seed, and he changes our world in ten years.

Michael, you’re working on a VR series too?

Muller: Yeah, I’ve been shooting primarily focused on sharks and changing people’s perceptions around them and raising awareness about the 100 million plus sharks that are being slaughtered every year. I’m doing that with my photography, I did some TV shows, I did clothing lines. But then VR came along, and I said, “Wait, this gives me an opportunity to take you underwater and see these things I’m seeing?” How many times do you get to see the birth of a new medium? I’ve never seen it happen, so I really jumped on it. You have to completely rewire how you shoot. You have to learn it all over again, how you capture, how you edit, how you tell the story.

“VR came along, and I said, ‘Wait, this gives me an opportunity to take you underwater and see these things I’m seeing?’ How many times do you get to see the birth of a new medium?” — Michael Muller

When Philippe talks about our ocean becoming a dump, he sees it. He’s out in the ocean regularly, as am I, and you see these plastics, or you see fewer and fewer fish. You see all these things happening, the coral being bleached. It’s like you just want to grab people by their necks and say, “Look what we’re doing to our planet.” That’s our life support system. No one would go into a hospital where your father’s on life support and just start unplugging plugs. We would do everything to keep that life support system, to keep that person alive. Yet we are destroying our life support system, and everyone knows it, but we’re all sort of like, “Yeah, well, okay, climate change is real, but…” What does it take for our government to say that it’s real, and we have to do something about it?

photo by Michael Muller

Cousteau: Let me give you an example on land: What if you wanted to catch rabbits, and you bulldozed an entire forest and killed all the birds, deer, squirrels, foxes, anything you could think of in order to catch those rabbits? You piled up everything else in a mountain of dead stuff—trees, bushes—and then you had a couple rabbits, and you walked away? People would lose their minds. That’s exactly what bottom trawling does for shrimp. It’s the number one killer of sea turtles and dolphins in the Gulf of Mexico, because they get trapped in these nets and drown. That would never be allowed on land. It’s just another example of what Michael was saying where we look out on the ocean, we kind of know it’s around, and we kind of choose to ignore the reality. Everybody says, “But I love shrimp cocktail.” Okay, and that’s a reason to just completely destroy the ocean? It sounds like nonsense to me. But, that’s why Kimberly [Muller] and Michael and Ashlan and myself are so focused on education. That’s what’s exciting and hopeful. Kids are definitely engaged and fired up in ways that our generation and previous generations weren’t.

Muller: I grew up watching his grandfather as a kid. That’s what got me first, what planted those seeds. So we’re taking that torch, and passing it on.

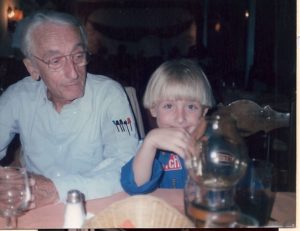

Philippe, what memories do you have of your grandfather?

Cousteau: One of my favorite stories is actually very relevant to VR and why I’m so interested in it as technology. I think I was about nine years old, so it was 1989. I remember we went into New York City to visit with him for dinner, and halfway through, my grandfather looked at me and said, “What do you think about this new Game Boy?” It’s coming up on Christmas and my grandfather was seventy-nine at the time. How many people in their seventies and eighties are constantly embracing new technology? But he was. In his wonderful French accent, he started talking about Game Boy, how he had one, and it played Tetris and Super Mario. He loved these new gadgets and tools. He said to me, “I know you want one for Christmas, and I know you’re very excited about it. But as you grow up and become a storyteller yourself, these are the kinds of tools that we need to be embracing—because games are not just a wonderful tool for entertainment. They’re a wonderful tool for education.” I never forgot that.

My grandfather was making The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and so many of his films and documentaries between the ’50s and the ’70s. There were six channels on television then, so your audience came to you. Now, there’s a thousand channels, the internet, social media, streaming, all these different things. It’s more important than ever that you go to your audience. I think that’s a fundamental shift in storytelling from forty years ago. We need to be on television, in books, in classrooms, on radio, and we need to be embracing new technologies like VR in order to empower a whole new generation. Where my grandfather could have a television show on Sunday nights, and thirty million people would tune in—now, that’s not the case.

Muller: As a kid, watching Jacques Cousteau, I think what stuck out to me—and I have this experience with my crew when we go out—is the camaraderie that would happen on board. His grandfather would be at the table with wine and the crew, and they would all talk. That’s what it’s like when you’re out to sea. It’s like you detach, you get off the grid. There’s no phones. It’s a bonding experience, and you’re connecting with nature in a way that I haven’t really found elsewhere.

Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Philippe Cousteau Jr. / photo courtesy of Voyacy Ventures

How has social media helped or hurt conservation efforts and education?

Muller: Listen, I think it’s great, because it’s a big bullhorn. It’s opened the gates. But if there was a button right here, and I could hit it and go back to 1999 and turn the internet off, I would. Because I don’t think the pluses outweigh the minuses. I think this has disconnected people. I go out to restaurants, I see a couple, and they’re both on their phones. You go to concerts, and everyone’s taping it.

Cousteau: This is a controversial statement, but I can’t think of anything that’s as pervasive in society—that has such a huge impact on our culture, in some cases our economy, our politics, our democracy—as Facebook. Yet if you switched it off tomorrow, I think you’d get a collective shrug in the world, except for maybe the investors. Although since it’s here, I think it does provide an opportunity to reach people directly. It’s very exciting for me to be able to do an Instagram video or something live when I’m on an expedition.

This year is the 75th anniversary of the Aqua-Lung, my grandfather’s co-invention—so it’s only been seventy-five years since we’ve really been exploring the ocean. Prior to that, all we knew about the ocean was what we pulled out in seafood, and what we dumped in. In the early days, the late ’40s and ’50s, my grandfather was a tinkerer. He broke his back in a car accident, and was told to swim in the Mediterranean to rebuild his strength, and was given a mask and goggles by his captain. He was in the French Navy at the time. He became frustrated that he couldn’t hold his breath longer, so he talked with an engineer, and they invented the valve that could allow people to swim like fish.

But that wasn’t enough, because he always loved filmmaking. So they tinkered more and basically took cameras and put them in a box, figured out how to waterproof it with a little button. There was no viewfinder, there was no focus. You had eleven minutes of film. You took it underwater, you pressed the button, you pointed it at stuff, and then you went up to the surface and swapped out the camera and did it over and over again. That was filmmaking just fifty or sixty years ago, in the early days of diving. At the end of the day, being able to film and photograph stuff and reach people in real time, right now, is amazing. This is just like VR: it’s the birth of a new thing, and as a society, we have to learn to balance it like anything else. I think we’ve been abusing [social media] lately. Hopefully, it will level itself out.

photo by Michael Muller

So how do we get people to recognize the horrors of what we’re doing to our oceans and actively respond?

Muller: It’s tough. When I was making my series, I chose to try and give people hope and make them fall in love with the ocean. I do believe people really protect what they love. I know personally, when I see these documentaries that show you the truth, you feel like you’re getting hit in the stomach. I think people watch it and say, “Well, what the hell can I do about it?” So then they’re like, “I don’t want to hear about it, because I feel so horrible.”

Cousteau: There’s enough doom and gloom out there. People know, generally, that there are problems. Beating them over the head with that is a short-term motivator. It’s been employed to great effect to get people to write a check and make a donation in the environmental movement, but in terms of long-term change, fear and negative reinforcement is not the way. You train dolphins, dogs, and human beings with positive reinforcement. Once you get people to take action, they’re much more likely to continue, have ownership, and raise awareness that lasts.

Are there any urgent policy measures people should know about?

Cousteau: I will not make a comment about anything else, because it’s not my lane, but from an environmental perspective, this administration is a disaster. All the changes in the EPA—there’s a coal lobbyist who’s in charge! How does that make any sense at all? But you know, we’re so focused on our federal elections that we ignore local elections. There are different issues all over the country that are important around renewable energy adoption, plastics, things like that. There’s lots of ballot measures that come up in various states—so get engaged in those kinds of things.

photo by Michael Muller

We need Republicans and Democrats. We need differing perspectives and viewpoints. But when one party really stands for the destruction of the environment, and one party stands for the support of the environment, that’s dangerous and scary and awful, and young people need to demand that both parties get back on the bandwagon. I always remind people that it was Richard Nixon who created the EPA. He passed the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the list goes on. The Republican of Republicans, and he was very pro-environment. It was a bipartisan issue back then. It wasn’t really until Reagan that it started to shift for various reasons; it was Reagan who dismantled the solar panels on the roof of the White House that Jimmy Carter had installed. But yeah—it’s a shame that we are in the political situation that we are right now. Some things should be universal, like putting the health of our children and the health of our communities first and foremost. FL