Instagram is usually a glut of images: selfies, foods, exotic locales, cute dogs. But Johnathan Rice’s feed is mostly filled with snarky words. Not many words, mind you—his specialization is the haiku, a Japanese poetry form occurring in five-seven-five syllable verses, just three lines total. Brevity is the soul of wit, after all, and people have short attention spans these days. Rice appreciates the ease with which he can summarize world events in real time on the internet, too: “So much of our culture today is a rush to immediate consensus,” he tells me. “Instagram allows me to react in the moment to anything—if one of the Jenners has a baby, I can get a poem out there within minutes.”

As for why he’s taken his poems to Instagram’s traditionally visual platform instead of someplace wordier like Twitter, Rice explains his intent is adding more playful #content to your selfie-cluttered ’Gram feed. “I was a reluctant hold-out to Instagram before I became a hopeless addict,” he admits. “I was too self-conscious for the selfie and I don’t get any pleasure from photographing myself. But then I started thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be funny to write what I now call dystopian haikus from the perspective of someone who’s trapped inside of a smartphone and can’t get out?’”

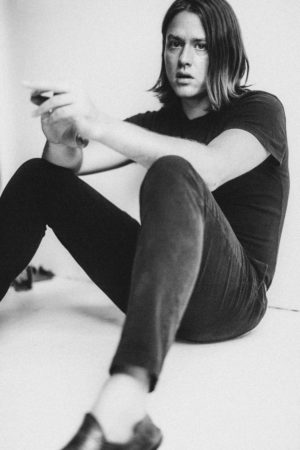

As a solo artist, the singer-songwriter has released three records and toured with R.E.M., Ray LaMontagne, and Pavement. The 2017 publication of his book of poetry, Farewell, My Dudes: 69 Dystopian Haikus, led to Rice’s newfound title as “the beat poet of the Instagram generation” according to W Magazine. He’s also known for his twelve-year relationship with songstress Jenny Lewis and their collaborations as Jenny and Johnny. This year, he released The Long Game via Mano Walker Records, his first solo full-length in six years. It’s a breakup album—he and Lewis split in 2015, and he began writing these songs circa 2014—but it’s not a total bummer record, either. The songs are alternatingly sad, funny, and hopeful.

Rice’s haikus are light-hearted but also rife with millennial anxieties. Themes include Twitter outrage, cancel culture, Trump and the dismemberment of American politics, technology’s encroachment on our inner lives, and the vanity of social media. A previously unpublished Rice haiku entitled “Millennials Nowadays,” for example, captures the modern importance placed on personal branding and promoting yourself online, as though a cohesive color scheme on Instagram can somehow stand in for a complex identity:

Rice’s haikus are light-hearted but also rife with millennial anxieties. Themes include Twitter outrage, cancel culture, Trump and the dismemberment of American politics, technology’s encroachment on our inner lives, and the vanity of social media. A previously unpublished Rice haiku entitled “Millennials Nowadays,” for example, captures the modern importance placed on personal branding and promoting yourself online, as though a cohesive color scheme on Instagram can somehow stand in for a complex identity:

Son, your mom and I

Are proud of the aesthetic

You have curated

Initially, Rice solicited some friends, a few who happened to be celebrities and influencers, to do dramatic readings of his poems for posts on Instagram; but more people began sending in clips, and now everyone from Anne Hathaway to Mandy Moore to Busy Philipps has participated. Rice praises Kat Dennings’ submission in particular, a video he calls “really high production value.” So far, the poem readers have all been female (“no men have sent me any. I’m gonna probably catch some hell for this, but I think men are less self-effacing?” Rice ponders of the gender disparity).

“So much of our culture today is a rush to immediate consensus. Instagram allows me to react in the moment to anything—if one of the Jenners has a baby, I can get a poem out there within minutes.”

Rice enjoys writing about the dystopian elements of the present day with a playful tone because of how somberly authors like Margaret Atwood or Ray Bradbury have always introduced dystopian futures—as something we’re forced into by an authoritarian government. “I don’t think any of those authors quite predicted that it would be totally voluntary, and we’d do it with gusto,” Rice says with a chuckle. “We gladly give away all of our personal information and privacy for free. Our reputations are similar to our chastity.”

But it’s not all bad news: Rice recently inked a deal with a major network for a TV show directly related to his poetry, and it’ll be his first foray into television. All he can reveal now is that he’ll be in the series, and “it will be an exploration of the new digital existence that runs parallel to our physical existence.”

Some of the lyrics on The Long Game mimic Rice’s satirical haiku persona (“I like you, you’re a lot like me” he sings on “Another Cold One”), but most are far more earnest and less tongue-in-cheek. The record was produced by Tony Berg, who told Rice he wanted to preserve the feeling of aloneness he’d heard in the songs. To hear Rice describe it, the process of writing the record coincided with an extremely difficult period in his life. But in listening to the whole thing, you’ll hear various stages of grief, with Rice ultimately coming out the other side more world-weary, but with renewed optimism (on album closer “Friends,” it’s apparent that he’s met someone new). Of the album’s themes, he recently told American Songwriter, “I have gained a newfound respect for lizards and sea cucumbers—animals that can regenerate after a major loss.”

Some of the lyrics on The Long Game mimic Rice’s satirical haiku persona (“I like you, you’re a lot like me” he sings on “Another Cold One”), but most are far more earnest and less tongue-in-cheek. The record was produced by Tony Berg, who told Rice he wanted to preserve the feeling of aloneness he’d heard in the songs. To hear Rice describe it, the process of writing the record coincided with an extremely difficult period in his life. But in listening to the whole thing, you’ll hear various stages of grief, with Rice ultimately coming out the other side more world-weary, but with renewed optimism (on album closer “Friends,” it’s apparent that he’s met someone new). Of the album’s themes, he recently told American Songwriter, “I have gained a newfound respect for lizards and sea cucumbers—animals that can regenerate after a major loss.”

“It’s the most alone I’ve ever been in terms of capturing performances in the studio,” Rice says of The Long Game. For a while now, he’s wanted to make a record he could tour by himself with an acoustic guitar—but he’s never had a collection of songs he felt were strong enough to flourish exclusively in that format. Until now.

“For years, I thought in order to be a singer-songwriter you had to have your hair in your face and be sad and project this withered archetype—but I’m kind of a goofball.”

The tracks are austere, Rice’s baritone sparse and unprotected. When he performs, he brings his haikus out on stage as well, periodically putting down his guitar and taking out a book of poems, a gesture he claims elicits looks of terror and hunts for the fire exits from his audience—until they realize he’s only reading haikus, which are quick.

“For years, I thought in order to be a singer-songwriter you had to have your hair in your face and be sad and project this withered archetype—but I’m kind of a goofball,” he says of the tonal distinction between his songs and his poems. “I’m not just one thing. I see myself as a writer, and above all, an entertainer. I think it was Bill Callahan, and I’m probably paraphrasing him, who said something to the effect of, ‘Once I realized I was an entertainer, everything got easier.’ I apply that to my own life. Once I realized that I get genuine joy and fulfillment out of entertaining others, everything opened up to me. I was the one restricting myself creatively. There’s nothing stopping any of us from doing exactly what we want to do. I can write jokes in the morning and sing sad songs at night.” FL

This article appears in FLOOD’s Passion Issue #2, powered by Toyota Corolla. Click to read or download the full issue below.