Devendra Banhart loves my shirt so much that he asks to take a picture of it. “I’m listening to Ned. I’m hearing Ned’s advice through his lyrics and he’s making me feel good. He’s bringing the sunshine in,” he explains. “Then I sit down here with you, and you’re wearing a Ned Doheny t-shirt. If there’s anything we can share with the world, it’s that that’s amazing.”

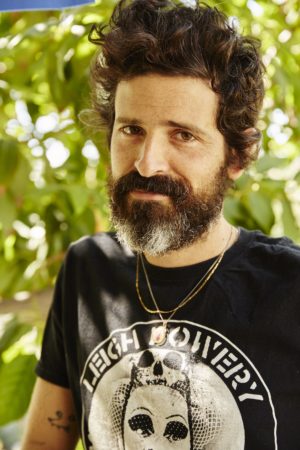

At a café in Echo Park, Banhart speaks with an enlightened ease, a sort of neo-hippie positivism that’s entirely unsurprising, given his roots in the so-called freak folk scene. The Los Angeles–based multi-hyphenate—songwriter, singer, guitarist, poet, and visual artist, among other endeavors—has just returned from a trip to Japan and is profusely, unnecessarily apologetic about his jet lag. I’d never have known he’d gotten so little sleep the night before, given his sunny demeanor and sustained expression of gratitude for our mutual love of an unheralded ’70s soft rock musician.

While in Japan, Banhart says he visited a record store that has a designated “quiet corner,” splashed with mellower offerings. “It had a bunch of Ned,” he explains. “His records are so beautiful. The covers are fabulous, and his early work is really folky and beautiful.” For ten minutes we gush over the shared interest, discussing what we know of Doheny’s backstory and his quotes in an essential music book, The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-On Collision of Rock and Commerce. “He has a very particular style, doing a mellow funk thing on acoustic guitar. It’s very rare,” he concludes.

It takes us a long while to get to the reason for this interview: Banhart’s excellent new record, Ma. If there’s anything to know, it’s that he’s more than OK with this sort of diversion, that he’d rather mark a cosmic musical occurrence between two strangers than spout on about himself. This extends to an advertisement we both notice for rising Los Angeles–based musician Cuco towering over Sunset Boulevard. “He’s a young guy just starting out—and wow, he’s on a billboard. It’s beautiful,” Banhart says.

It takes us a long while to get to the reason for this interview: Banhart’s excellent new record, Ma. If there’s anything to know, it’s that he’s more than OK with this sort of diversion, that he’d rather mark a cosmic musical occurrence between two strangers than spout on about himself. This extends to an advertisement we both notice for rising Los Angeles–based musician Cuco towering over Sunset Boulevard. “He’s a young guy just starting out—and wow, he’s on a billboard. It’s beautiful,” Banhart says.

It’s no surprise that Banhart’s a fan of both Doheny and Cuco. The pan-cultural, era-straddling essence and underlying groove of Ma embodies each of these musicians’ works. Far from Banhart’s origins in acoustic guitar-and-voice, Ma is a layered, lush, and lightly funky statement with strings, horns, and keys—one that draws from a deep well of ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s influences, but with the whimsy we’ve come to expect from perhaps the most earnest of absurdists since the Mael brothers of Sparks.

“People can be jaded about this idea that we need to elevate and celebrate the matriarchy. But in 90 percent of the world, femininity is incredibly suppressed.”

Take the video for album standout “Kantori Ongaku,” a sax-laced, Lou Reed–indebted light groove that pays homage to Japanese pop music and Venezuela, where Banhart’s family is from. It opens with a pony pissing on the floor, and ends with model Emily Labowe spewing fake yellow vomit into Banhart’s face. In between, he dons a yellow, blue, and red unitard (the colors of the Venezuelan flag), a teal one-sleeve dress, a white towel, and a red-and-white custom suit by LA designer Canvas By Giraffe, all while caressing a mysterious brunette Rapunzel braid.

But kaleidoscopic and jam-packed as the video is, its concept is simple. “Haruomi Hosono has a song that’s all in Japanese, but in the chorus he says ‘country music’ in English, so I thought it would be cool to reverse that,” Banhart explains. It’s the reason he sings the title phrase in Japanese, one that loosely means “country music,” and the rest of the song in English.

True to many of his previous records, Banhart sings some songs in Spanish, and one in Portuguese. It’s a decision he says isn’t conscious, but comes with the flow of the words. “I’d actually like to write a song in every language, that would be fun,” he considers. It seems natural given Banhart’s extensive travel, but in an increasingly anti-immigrant American political climate, such global celebration also translates as a gentle form of protest—one that doesn’t hit the listener over the head, but promotes diversity and inclusion simply by existing. “Some people might be karmically more attracted to something a little more intense, and sometimes that’s needed,” he says. “But this is something that’s open to interpretation, something that can be applicable to quite a few different circumstances.”

True to many of his previous records, Banhart sings some songs in Spanish, and one in Portuguese. It’s a decision he says isn’t conscious, but comes with the flow of the words. “I’d actually like to write a song in every language, that would be fun,” he considers. It seems natural given Banhart’s extensive travel, but in an increasingly anti-immigrant American political climate, such global celebration also translates as a gentle form of protest—one that doesn’t hit the listener over the head, but promotes diversity and inclusion simply by existing. “Some people might be karmically more attracted to something a little more intense, and sometimes that’s needed,” he says. “But this is something that’s open to interpretation, something that can be applicable to quite a few different circumstances.”

Banhart reveals that in the album there are references to the crisis in Venezuela, without saying as much. “There’s imagery about a supermarket covered in blood, a museum that’s been bombed out, lines of people waiting to eat, people being kidnapped,” he says. “This is happening all over the world. I wanted something that could apply to injustices happening in other countries, too.”

The intent ultimately becomes clear through Banhart’s actions. The “Kantoro Ongaku” video solicits charitable donations for Venezuela at the 1:30 mark, and Banhart’s donating $1 from each concert ticket sold to World Central Kitchen, a not-for-profit that provides meals in the wake of natural disasters. The album’s title, too, defends a feminine energy currently under siege. “People can be jaded about this idea that we need to elevate and celebrate the matriarchy,” he says. “But in 90 percent of the world, femininity is incredibly suppressed. And I’m like, ‘Wow, you live in such a bubble that you think this isn’t a problem? You’ve probably never left your house.’”

Amid his concerns, Banhart finds room to chuckle, a necessary coping mechanism between barrages of bad news. “Can I just say, Ned Doheny to you,” he deadpans at the end of our conversation. “May you have a Ned Doheny day.” FL