In a corner of an ornate green room at Highland Park’s Lodge Room, Penny Van Hazelberg and Lee Nania fidget as they contemplate the moment they became comfortable as a band. It’s the second time that their Australian-based but online-bred act Surfing is headlining the venue this year, but imposter syndrome is hard to kick. Despite a cult following that shows up to their sets in homemade merch and turn their records into bonafide Discogs collectibles, Van Hazelberg is still grappling with the fact that he’s a singer in a band. “I think the vocals have become clearer as I’ve become more accustomed to being a lead singer,” he tells me later via email. “It’s not really something I wanted to be, but maybe I’m growing into it? I don’t know!”

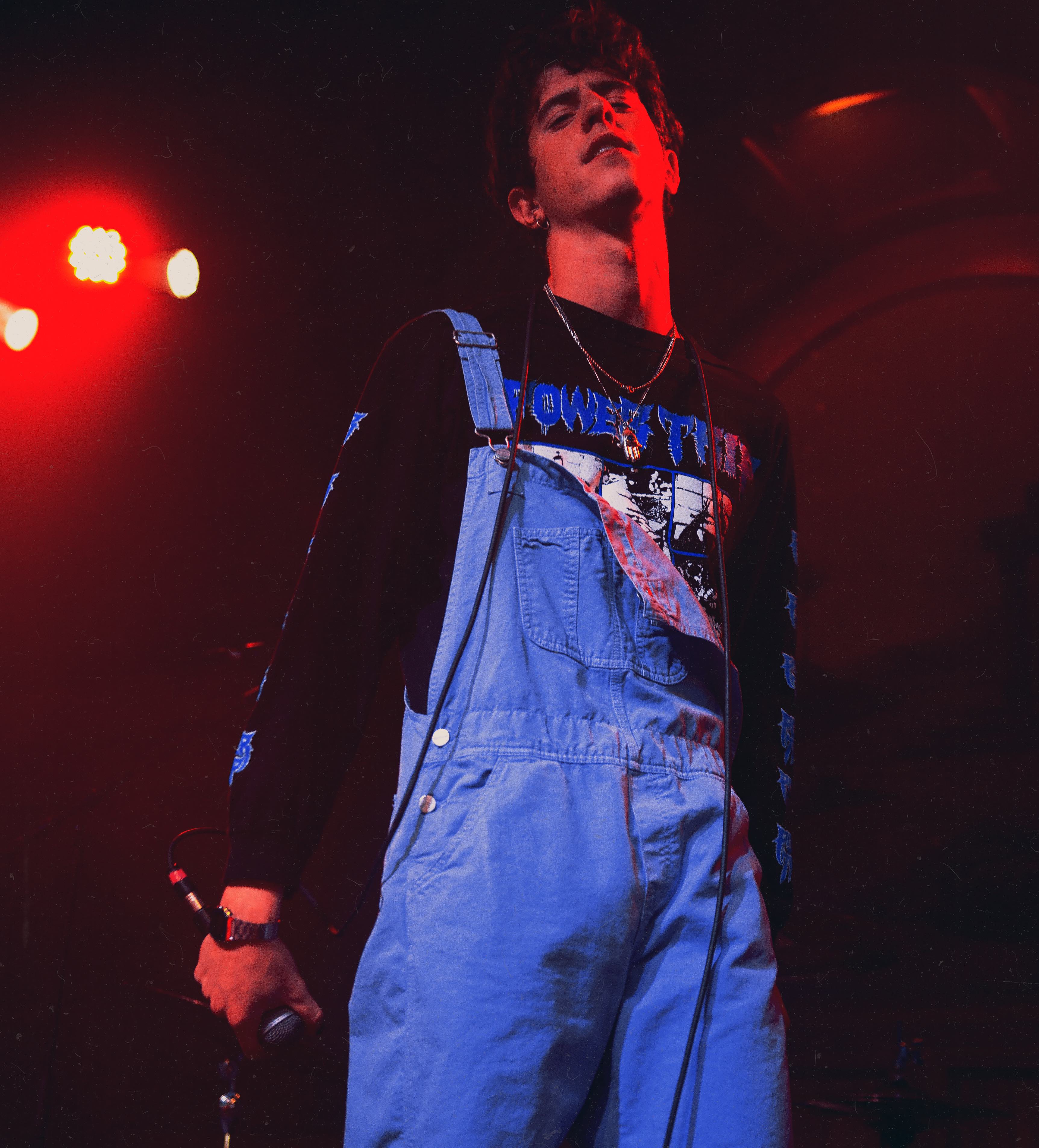

They eventually emerge on a blue backlit stage, never materializing beyond hazy silhouettes as the venue’s fog machine works overtime. Despite releasing their new record, Emotion, the night before, Van Hazelberg and Nania run through a handful of tracks from Deep Fantasy, their viral debut that some consider a demarcation line between chillwave and its infinitely more Online cousin, vaporwave.

Meanwhile, from the back bar, George Clanton and Lindsey French finally find a spare moment to watch their first success story as label owners play out.

It’s not in their folksy nature to admit it, but the co-heads of the label 100% Electronica are inarguably the most recognizable people in the room. French’s own music as Negative Gemini capitalized early on this generation’s shuffled sense of eclecticism, sliding from techno pop and drum and bass to lo-fi slacker rock with playlistable ease. Clanton, meanwhile, took a bookish devotion to new wave and the irony-free positivity of alt-reggae titans 311 in his pursuit of creating arena-sized anthems for outsiders.

Still, popularity isn’t particularly interesting to either artist if they’re not sharing the wealth. “I’m crazy about increasing my reach and I want to work with people who want to be heard,” Clanton insists the following afternoon. “You don’t have to show your face. You can wear a ghost outfit on stage and be invisible to everybody. That’s fine.”

In under five years, 100% Electronica have bolstered the once-insular vaporwave community with a catalog of highly sought-after releases, the first festival devoted to the genre, and a sense of IRL community—even as popular online opinion deemed vaporwave extinct.

If anything, its touchstones of sampling tape-warbled muzak, pitched-down soul singers, and Japanese lettering on its covers have given way to a new crop of creators operating outside its once-rigid guidelines. The metal-leaning vocals of Fire-Toolz acceptably falls under the vaporwave umbrella as comfortably as the self-proclaimed “knightrock” of Equip, pop deconstructionism of death’s dynamic shroud.wmv, or future funk rebirth in Skylar Spence.

Some would go so far as to claim vaporwave as the vanguard of anti-capitalist punk; but to others, it remains the soundtrack for the internet’s endless shitposting, nostalgia porn, and, at worst, violent ideologies. In reality, the state of vaporwave is…well, kind of a long story, but Clanton and French have positioned themselves somewhere close to the center of it, encouraging the scene along with a movement of radical positivity and letting the genre be whatever it needs to.

![]() In a sleepy neighborhood in Atwater Village the morning after Surfing’s show, Clanton and French’s mini-compound is remarkably quiet despite its current state as a hostel for transient musicians. George and Lindsay give a sheepish tour of their house and garage shipping space, peppering in regular apologies for the state of post-tour disarray. They both hunker down in their living room as if they haven’t sat down in weeks—which, given the months of planning that went into the debut Electronicon festival just the weekend before, is entirely plausible.

In a sleepy neighborhood in Atwater Village the morning after Surfing’s show, Clanton and French’s mini-compound is remarkably quiet despite its current state as a hostel for transient musicians. George and Lindsay give a sheepish tour of their house and garage shipping space, peppering in regular apologies for the state of post-tour disarray. They both hunker down in their living room as if they haven’t sat down in weeks—which, given the months of planning that went into the debut Electronicon festival just the weekend before, is entirely plausible.

Still, a flair for grandiose gestures has become an expected and defining trait for the couple, dating all the way back to the first night they played a show together in 2011.

“The electronic music scene is kinda small in Virginia where we were both living at the time, [but] he said to my brother, ‘Alex, I’m going to marry your sister,” French recalls. “We’re not married, but…”

“Practically,” Clanton interrupts. “Just too busy.”

“Anyone interested in releasing my music…I might as well just do it myself, be in full control, and get 100 percent of the revenue. It was an easy call for me to make at that point.”

— Negative Gemini

French was seeing someone else at the time, so the two remained friendly acquaintances. In late 2013, Clanton posted online asking for a travel buddy to a New York show he was co-headlining under his late Mirror Kisses moniker. French reached out, partially just to see some friends in the city. “We were friends, I guess?” she says, looking to Clanton.

“I was already interested from two years ago,” he deadpans. “But, y’know, I wasn’t worried about it. There was no chemistry or interest. She just wanted to go to New York.”

The show was one of the first at Brooklyn venue Baby’s All Right alongside fellow vaporwave producer Ryan DeRobertis. DeRobertis, better known as Saint Pepsi before and after his stint as Skylar Spence, would go on to be one of the first artists in the scene to parlay dorm room mixtapes chock full of unlicensed samples into a legitimate record deal.

“It was maybe a week into me releasing mixtapes on Bandcamp and George was one of the first people that friend requested me,” DeRobertis recounts in a separate conversation over the phone. “He sent me a message like, ‘Are you Saint Pepsi?’ I said yeah, and he said, ‘That’s cool, I have a secret vaporwave project too. We both sampled The Whispers, though, and that can’t happen again.’ Like, typical George humor.”

George Clanton and Negative Gemini

“We were kinda up-and-coming, trendy a little bit at that time,” Clanton adds. “He was getting written about, I was getting written about, both of us for the first time that year.”

“It sounds so silly to say, but we were nobodies,” DeRobertis interjects with a laugh. “When I heard George’s music, though, it was so authentically new wave, like the type of stuff we had bonded over in conversation. I was blown away. It was my everything, like I found my place in the world when I first heard [Mirror Kisses’ song] ‘Runaways.’”

The Baby’s All Right show became a key point in all three musicians’ timelines. It was the first time Clanton and DeRobertis ever got the green room treatment, complete with a bottle of CÎROC they considered pawning off for money. More importantly, it was the night they discovered their mutual ambition to do something greater within vaporwave, even if they couldn’t articulate what that was yet.

“For a lot of people who grew up listening to anachronistic music like George and I, vaporwave felt sort of vindicating,” says DeRobertis. “We pushed through the weird long enough that the weird became acceptable. As such, all we want to do is to continue to make the weird acceptable and get into the weirder and make that accessible.”

After that night, Mirror Kisses and Saint Pepsi’s online bantering transitioned into a trusted friendship as their success stories began taking a similar arc. And, although they still debate the exact timeline of events, Lindsey and George began dating shortly after their road trip.

![]() When French started courting offers for the next Negative Gemini album, and Clanton agreed to release a single with a small, Brooklyn-based label the following year, both were swiftly met with the harsh reality of bringing online music offline.

When French started courting offers for the next Negative Gemini album, and Clanton agreed to release a single with a small, Brooklyn-based label the following year, both were swiftly met with the harsh reality of bringing online music offline.

“They just put the song out and nothing happened,” Clanton says dismissively of his former label. “I never got paid and I still think they’re serving that song online from seven years ago.”

“I was in the same boat,” French adds. “Anyone interested in releasing my music [was] at a level that, y’know, I might as well just do it myself, be in full control, and get 100 percent of the revenue. It was an easy call for me to make at that point.”

“For a lot of people who grew up listening to anachronistic music like George and I, vaporwave felt sort of vindicating. We pushed through the weird long enough that the weird became acceptable. As such, all we want to do is to continue to make the weird acceptable and get into the weirder and make that accessible.”

— Saint Pepsi

The plan to start 100% Electronica began in earnest: Instead of trudging along unsigned, they would put down some money to print records and further their artistic legitimacy under the guise of a mysterious label. Using his straight-ahead vaporwave side project ESPRIT 空想 as 100% Electronica’s maiden release, Clanton took out a credit card with a two thousand dollar credit limit, maxed it out to print two hundred records, and sold them while slowly paying off the card. He repeated that cycle for the label’s first few releases.

“I feel like the birth of a record label is when people start telling you that you have a record label,” Clanton attests. “It took a little while until we were a serious force, but releasing that Surfing record that first time was big.”

Clanton found Surfing’s Deep Fantasy well after its 2012 release by letting YouTube’s then-nascent “recommended” algorithm run uninterrupted. While the album’s take on syrupy psych rock imbued with vaporwave’s sample-heavy nostalgia was already in high demand for a vinyl release, 100% Electronica had to do some convincing to press four hundred copies. Van Hazelberg and Nania were certain Clanton would be stuck with at least half of the records. The pressing sold out within six hours.

“We were just really successful in the first five or ten releases, so then the label had money to print more records and to take some risks,” says Clanton.

Specifically, they wanted to see how far outside the bounds of vaporwave their label could go, starting with a release from Mac DeMarco–adjacent psych duo Tonstartssbandht and a repress of Clanton’s favorite record from the ’80s, Everybody Is Fantastic by Irish sofisti-pop act Microdisney.

“They’re super unknown stateside,” DeRobertis asserts of the latter. “Like, their claim to fame is that one half of the duo went on to form The High Llamas and do string arrangements for the big Stereolab albums. So when George repressed that album, to me, it was insane.”

“It was a misstep,” Clanton admits of both releases. “We printed up a bunch of records, we sold a hundred immediately, and then none…we realized that, OK, it’s not just about whatever weird music George Clanton thinks is good.”

“I feel like the birth of a record label is when people start telling you that you have a record label.”

— George Clanton

100% Electronica’s refocusing back toward vaporwave couldn’t have come at a more crucial moment. As a growing majority of online critics began treating vaporwave like a passing trend, the remaining scene saw a rise of alt-right supporters terraform their sound and aesthetics to better fit their belief system. The brief-but-damaging movement was named fashwave, the “fash” short for fascist.

Other than using white supremacist dog whistles as song titles and sampling speeches from Hitler and Trump, fashwave intentionally did little to differentiate itself from its source material, even creating fake accounts for prominent vaporwave artists like Clanton and French.

“We had one person make a Twitter account that was devoted to making both of us look like we were Trump supporters when, in fact, we are passionately not,” she recalls. “There was a fake Lindsey account saying ‘Bring your guns to the shows just in case any Muslims come,’” Clanton adds. “We’re not a political label, but it’s definitely important to be the good guys.”

Fashwave was undoubtedly the nadir of vaporwave, but a growing culture of gatekeeping, rigid sonic expectations, and scene in-fighting had already eroded much of the joy Clanton once saw in the community. In short, if 100% Electronica was to continue as a vaporwave label, it was going to represent the kind of scene Clanton and French fell in love with, not what it had become.

George Clanton

“Vaporwave, to me, is a positive movement of people making music online,” Clanton asserts. “I’m using this platform to spread this idea of, like, ‘Look what we can accomplish when we’re being the nice guys.’ You don’t have to be edgy to be interesting. Actually, edgy’s kind of played out. What’s new and exciting is being kind of anti-ironic, anti-disingenuous.”

In 2015, Clanton released 100% Electronica, his first album under his own name. With the off-kilter conviction of a lost new wave classic, 100% was Clanton at both his most accessible and alien, reaching for the stratosphere with his histrionic croon tied to pop choruses. The following year, Negative Gemini released Body Work, a kaleidoscopic mix of drum and bass, trance, and warped bubblegum pop for the post-club ride home. Arguably the furthest from vaporwave 100% Electronica had ventured, Body Work sounded like the work of an artist completely unburdened by genre distinction.

Still, French and Clanton continued to find acceptance under the thriving vaporwave tag on Bandcamp, proving to the genre’s old guard that a revival was not only possible, but something to be potentially excited for.

“If George’s solo music can be considered vaporwave, that doesn’t affect anybody negatively,” DeRobertis states. “It only shines a light onto the community and it shows that people are supportive of the music and the people behind it. If it’s good and your PR tactic is calling it vaporwave, who cares?”

“[George and Lindsey] aren’t making vaporwave in a strict sense, but they are cooking a large recipe where vaporwave is one of the main ingredients.” — Equip

While 100% Electronica’s first new era signees admittedly fit more comfortably within the classic vaporwave tradition, their attitudes aligned perfectly with the label’s newfound vision for the genre. The label signed off on Satin Sheets—their first and only signee by mailed-in submission—based on the strength of his prolific output and positive initial correspondence online. Clanton, meanwhile, was the one to DM Equip, a Chicago-based producer whose embrace of 16-bit video game soundtracks and dream pop is a case-in-point for the unexplored frontier still left in vaporwave.

“I’m always looking through the vapor-lens and seeing what new influences I can pull in here,” Equip’s Kevin Hein writes via email. “I like what George and Lindsey have done with the genre. They aren’t making vaporwave in a strict sense, but they are cooking a large recipe where vaporwave is one of the main ingredients.”

“Being nice is a huge part of it. I feel like that’s what separates our corner of the genre versus what it was a few years ago,” Clanton reckons. “It took us a long time, but now it seems like we’re kind of driving the ship. [Our] message is coming across loud and clear because we’ve got a big fucking megaphone that the little grumblers don’t have. Whoever’s talking the loudest is telling the story and, right now it’s us, thankfully.”

![]() In late 2018, during a beach getaway in Miami, Clanton and French plotted their next move as new figureheads of a mostly online-bound music scene. Instead of continuing to live with French’s parents rent-free, the pair made the joint decision to uproot their lives and get to work on their most ambitious project yet in a city thousands of miles away from home.

In late 2018, during a beach getaway in Miami, Clanton and French plotted their next move as new figureheads of a mostly online-bound music scene. Instead of continuing to live with French’s parents rent-free, the pair made the joint decision to uproot their lives and get to work on their most ambitious project yet in a city thousands of miles away from home.

“The only reason not to was because our families are on the East Coast, so that was kind of a hard thing to shake,” French says. “I used to have a dog, Cody, and I was overly protective of him because he would run away. I would only let my mom and dad watch him. I kinda stayed close to them for that reason, so they could watch my dog.”

“Cody passed and then we took a trip to Miami for a week, like, the next day,” Clanton recalls. “We just had all of these points saved up because we hadn’t been able to travel for four years, so we took a points trip. While we were on the beach, we signed the lease to this place.”

In the weeks before relocating to Los Angeles, Clanton released Slide, a self-proclaimed “vaporwave opera” that took the euphoria of 100% Electronica and somehow amplified it further with higher production value, two of his biggest singles in “Make It Forever” and “Dumb,” and acid house flourishes throughout. The album landed praise from the likes of i-D, The Needle Drop, and Pitchfork, the last of which called Slide “the true introduction to George Clanton.”

To some, Slide was the true reintroduction of vaporwave, which Clanton sought to capitalize on with his biggest idea yet: Electronicon, the first festival dedicated to the genre.

“I think it’s kind of always been something that people have talked about,” he says, citing a failed attempt years before called Boogie at the HyperMall. “Years go by, no one else did it, and we just kept getting bigger and bigger. I got a booking agent and that was the tipping point.”

“You don’t have to be edgy to be interesting. Actually, edgy’s kind of played out. What’s new and exciting is being kind of anti-ironic, anti-disingenuous.” — Clanton

Still, planning Electronicon while running 100% Electronica and promoting a new album was already stretching the label thin before Clanton broke his leg on stage opening for Beach Fossils this past April. They took the injury in stride with new merch, but the need for new team members was undeniable. Around that time, an unlikely aid and friend arrived in local musician Aaron Shadrow.

“George and I had somewhat of a tumultuous history as fan and artist,” Shadrow recounts over the phone. “The first time I saw him live, he and Lindsay made fun of me to my face about something I said on the internet, so I really didn’t like them. Then, a few weeks before they moved to LA, I told them that they sounded like rednecks on an Instagram live stream and then they hated me.”

After a predictably uncomfortable in-person meeting, Clanton offered Shadrow a paid internship with the caveat that there weren’t any motives on his part toward getting a record deal for his project, Game Boi Adv. He agreed, subsequently getting something much better in return: a front row seat to 100% Electronica’s most chaotic year yet, culminating in the first Electronicon selling out within hours.

Aaron Shadrow

“I feel like it’s a new precedent in the vaporwave community,” Shadrow attests. “There are very few artists performing frequently and very few meetups, so the scope of going from nothing to a giant, sold out festival was absolutely unbelievable to see.”

Clanton, admittedly too distracted with securing vegan-friendly vendors and plotting how to prevent a day-long festival from combusting into Fyre Fest 2.0 to celebrate, never seemed to doubt the potential success of a festival. Even the idea of booking a dozen artists that rarely (if ever) perform wasn’t a logistical concern.

“There were a few hard sells and a lot of easy sells,” Clanton says. “Everybody always wanted to do something like this…[and] everyone that was there really put their all into it. They’re serious artists.”

Over one late August afternoon in Bushwick venue complex Elsewhere, the first Electronicon unfolded like a technicolor sensory overload. Between Equip haunting the stage in movie-grade demon makeup, Negative Gemini starting the only mass dance party of the day, and Clanton’s triumphant return post-leg break, Electronicon was a festival without hierarchy, as every act teemed with headliner-level theatrics. Still, the festival decisively had its own “Coachella moment” with the announced return of Saint Pepsi.

“I never wanted Saint Pepsi to have to be revived,” DeRobertis admits earnestly.

“Our message is coming across loud and clear because we’ve got a big fucking megaphone that the little grumblers don’t have. Whoever’s talking the loudest is telling the story and, right now it’s us, thankfully.”

— Clanton

After signing to Carpark Records in 2014, DeRobertis received a cease-and-desist from Pepsi’s legal team, forcing him to bury his stage name. After rebranding as Skylar Spence and delivering a promising, pop-driven debut with Prom King in 2015, DeRobertis found himself in a creative rut after a string of festival appearances. While managing bouts of depression and thoughts of abandoning his music career, his label respectfully shelved a darker second Skylar record, encouraging him to aim for Prom King’s bubbly highs. When Clanton invited DeRobertis to headline Electronicon as Saint Pepsi, the plan was initially a lighthearted and much needed one-night revival.

“It all came together when George proposed the Electronicon mixtape, the cassette that everyone who bought a ticket got as they walked in,” DeRobertis recalls. “He asked every artist for a song for the mixtape. I misinterpreted that as him wanting new material, but I was also at a place where I jumped at the opportunity.”

DeRobertis used it as an exercise to cobble together a song like he used to as Saint Pepsi, turning over “Myself When I Am Real” in a matter of days. After sending it in, DeRobertis regretted the idea that only Electronicon attendees would hear the song and, on a whim, started digging through his hard drives for other lost work. He emerged with a new Saint Pepsi record, Mannequin Challenge, which he released the day before Electronicon with virtually no warning to his fans, the 100% Electronica crew, or even Carpark. “Mannequin Challenge was a race to the finish to put together a cohesive piece of work,” he says. “In the span of two days, I could do three, four, or five more songs.”

DeRobertis could’ve easily turned in a rush job compilation for fans, but Mannequin is both a proper burial for Saint Pepsi and the fulfillment of his plunderphonic pop promise before Big Soda broke up the party. The Saint Pepsi set at Electronicon had suddenly become a victory lap, spanning a career that DeRobertis assumed was near its end.

“I played a lot of real old, deep cut songs during my set and they come with a lot of baggage,” he admits. “They come with the disappointment that I brought home to my parents when I was dropping out of school because I was depressed and skipping class to make vaporwave. Whenever I would start any new song, it was like being at a Porter Robinson concert…it felt like I was back in 2013 having a dream about my ideal life and I could wake up at any moment.”

The truly unbelievable reality was that DeRobertis wasn’t alone in the dream. Comments on the festival’s live stream resembled the awe of a collective alien sighting or once-in-a-century meteor shower. Fellow artists on the roster learned each other’s real names that day and grabbed beers for the first time backstage. After a well-documented rooftop set against the New York skyline at sunset, anonymous producer t e l e p a t h reportedly told DeRobertis that he now understood the appeal of live performance after years of avoiding it.

Both French and Clanton lost count of how many people told them that Electronicon was the best day of their lives, which Clanton rationalizes in the only way he knows how: with a 311 quote.

“They’re kind of the inspiration to it all,” he attests. “At the end of their show, they say ‘Be positive and love your life’…what we saw at Electronicon, I want to breed that into the music scene. There’s no equivalent to it, the kindness, going to this show in fucking uptight New York and strangers are high-fiving each other for no reason.”

For now, greater hypothesizing about vaporwave’s future has to wait. The second Electronicon, this time in Los Angeles, is ramping up for October 19. Murmurs of upcoming collaborations and music are already bubbling out from the first Electronicon roster. Shortly after our conversation, Clanton himself fulfilled a longtime dream and released a pair of collaborative songs with his idol, 311 frontman Nick Hexum.

There’s always pressure, more plans to finalize, more things to do than hours in the day, but Clanton and French buzz about it like textbook workaholics. They’ve already pulled off a successful label, separate music careers, and a scene-encompassing festival. If Electronicon 2’s announcement video is meant to be taken as a literal mantra, the sky’s the limit—as long as 100% Electronica keep giving and being a reflection of their fans.

“That’s kinda my personality,” Clanton concludes. “I’m never gonna say no to a high five from a fan.” FL