The pre-eminent guitar hero of the post-punk era, Andy Gill hoovered up stray bits of Jimi Hendrix, Velvet Underground, Dr. Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson, and Stax Records’ funkier sides, and sprayed it all back out like a cannon blasting grapeshot.

Gill’s jagged, angular, tightly-coiled, feedback-laced approach to axe-strangling would have been incendiary enough in its own right. But fused with the cerebral socio-political commentary and lean art-funk-dub grooves of his band Gang of Four, it made for a spectacularly bracing concoction that profoundly influenced R.E.M. (who toured with Gang of Four in the early ’80s), Red Hot Chili Peppers (whose debut album was produced by Gill), Nirvana, Rage Against the Machine, Sleater-Kinney, Franz Ferdinand and hundreds of other artists.

Formed in 1976 in Leeds, England, following a trip to New York City where Gill and fellow Leeds University student Jon King rubbed shoulders with the leading lights of the CBGB’s-centered punk scene, Gang of Four would be justifiably legendary today even if they’d only released Entertainment!, their brilliant 1979 debut. But with the exception of two major hiatuses—one from 1983 to 1987, and the other from 1997 to 2004—Gill continued to boldly lead the band through a number of lineups, incarnations, and albums. He was even, according to the surviving members of their current lineup, “still listening to mixes for the upcoming record and planning the next tour” during his recent hospitalization for a severe respiratory illness. Sadly, those tour plans would be for naught; Gill passed away on February 1, at the far-too-young age of sixty-four.

I had the great pleasure of interviewing Andy Gill about five years ago, when he was in Los Angeles to do promo for What Happens Next, the band’s first album without Jon King on vocals. Though the interview was ostensibly for a short piece in a guitar magazine, we wound up talking for an hour about everything from Gang of Four’s unusual “egalitarian” musical formula to his ill-fated audition for Mick Jagger’s touring band. An absolute gentleman, Gill jovially answered every question I had for him, even though he was clearly feeling rather worse for wear when he arrived, about an hour late, for our chat.

“My flight was delayed, so I got in really late last night,” he apologized while ordering us a round of pints. “And then I came down here to the hotel bar and had a couple of martinis, and then these drunk English bankers came up to me. ‘You’re Andy Gill, aren’t you?’ ‘Yes, I am.’ ‘Let me buy you a drink!’ So a mojito appears… I crawled into bed at like three o’clock, and woke up at six with jet lag. So I’ve had no sleep, and I’m absolutely fucked.”

The new record is a bit of departure from previous Gang of Four. You’ve got Alison Mosshart singing on a couple of tracks, and a couple of other vocalists, as well. It really sounds like a new chapter for you.

Oh, absolutely. I think every Gang of Four record sounds different from the last one. The guitar playing, you can sort of tell it’s me—but there’s a different sound with every record. Entertainment! was one sound; it was that sort of dry, brittle, very crisp, you know. And then it completely changed for [1981’s] Solid Gold, which was much darker, with some effects, a little tremolo… And then, [1983’s] Songs of the Free had a lot of sustain-type of things… It always changes. I think the thing that’s always consistent is that obsession with rhythm and groove; that’s always there.

When you’ve gone through these changes, what usually dictates it? Is it because you fall in love with a new type of sound?

Yeah, yeah… To be honest, it’s hard to remember exactly what I was thinking when we did Solid Gold. [Laughs.] Entertainment! was done completely amateurishly, like totally… I was sort of the main producer and voice, and I didn’t know what I was doing. So it was like real primitive, amateur stuff, in a very weird studio. The room was a decent size, but it had carpet on all the walls to make it super-dead.

Very ’70s!

Very early ’70s, yeah. And that’s reflected in the sound. In a weird way, one of the reasons that Entertainment! has aged relatively well is because it doesn’t have a sound that pins it down to the time; it’s just an exciting, groovy, dry thing. But with [2011’s] Content, our last album from a few years ago—to be honest with you, I think it’s a much less-good record than this new one. Somewhere on some level, there was a feeling of “Let’s reach back and re-connect with Entertainment! and Solid Gold!” Which was kind of a mistake, I think.

It’s interesting to hear you say this, because Content sounded great when I first heard it, like, “Oh, they’re going back to that old sound!” But after two listens, I put Content away and went back to those original records.

Exactly! You’ve said it in one, there. But with this record, because there was a major upheaval—Jon’s gone, but I’m determined to do something great; if it isn’t great, I’m going to look really stupid. I think the first thought was, “I want to do some collaborations.” And I’ve wanted to do some collaborations for a long time, but that wasn’t something that really flew with Jon King.

And number two was, “I’m not going to have any rules about what you can and can’t do—I’m not going to look back and say, ‘What is the Gang of Four thing?’ I’m going to do whatever I please, and follow whatever it is.”

Every time I make a record, I feel like I’m basically starting from a blank slate. And I’m usually coming up with different answers because, you know, time moves on and we’re doing different things. Things change.

Hence the new album’s title.

Exactly. I think the reason that Entertainment! was an exciting record for people was because it came up with a fresh sort of language. It wasn’t something that was a re-hash, it wasn’t new wave, it wasn’t this or that. It wasn’t a genre; it was new. And I think Gang of Four is at its best when it’s reinventing the wheel.

“Entertainment! was an exciting record for people because it came up with a fresh sort of language. It wasn’t something that was a re-hash, it wasn’t new wave, it wasn’t this or that. It wasn’t a genre; it was new. And I think Gang of Four is at its best when it’s reinventing the wheel.”

When Jon left, how soon was it until you started thinking about making another Gang of Four album?

I think pretty much straightaway. I’d been expecting it for a bit; he’d given enough hints. We’d done two weeks in Australia, festivals and all that, and very shortly after that we did a gig in Brussels; and before the gig, he said, “You know, I’m out of here.” And at that point, I said, “Well, you understand that I’m carrying on with it, don’t you?” And he said, “Yeah, absolutely!” So it was pretty much instant.

Did Jon’s departure make you reconsider the role of your guitar in the band’s sound?

One of the signature things about all Gang of Four records is that the guitar is a part of the ensemble. There’s the drums, there’s the bass, there’s guitar and the voice, and they all have to inter-lock like a Swiss watch; if one bit’s off, it doesn’t work. And it’s the antithesis of the traditional structure, where you have the hierarchy where on top you’ve got the vocals—that’s the loudest things—and you go down from there with the guitar, keyboards, and at the bottom you’ve got bass and drums.

I remember listening to an Oasis record which very much follows that; it was almost like, “Are there drums on this record?” I mean, literally, I was turning it up, trying to hear if there were any drums at all. I wasn’t sure! [Laughs]. And that’s fine, you know. I’m not a big Oasis fan, but that’s the model that people have been using to make records since time immemorial.

But with Gang of Four, it was modeled more on the idea of egalitarian, communal activity, which was very much trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. [Laughs.] That’s always the way the band worked, from a musical standpoint. In fact, people from time to time say to me, “Oh, Andy, can you play the guitar part from—?” And I say, “There’s no point; it would sound like shit. It only makes sense when you’ve got drums and bass playing along with it.”

It’s funny you should say that—I used to play “I Found That Essence Rare” with my college band. But I picked up the guitar last night to play it, and it didn’t sound so hot by itself.

That’s one of the songs where you could do that, though. It’s one of the more conservative tracks on Entertainment!, in a way. “Essence Rare” was one of the earliest songs from that record; we were still looking over our shoulder a bit at punk rock. And it’s a cool track, people love it. But my favorite song on that record is “Not Great Men,” because that thing I was looking for—that marriage of spiky rock guitar with funky bass and funky drums—that one nailed it more than any other of the early songs. That was one of the last songs we wrote for that record; it finally arrived. We’d found it!

I know you’ve been using a Fender Stratocaster for decades, but was that what you used on Entertainment!?

The Strat’s been my main guitar since the late ’80s, and I had a Burns guitar earlier on… I used to do this stupid thing, like on the song “Anthrax” on Entertainment!, where I’d get all this feedback by banging the guitar on the amp. I destroyed so many good guitars just banging ’em around and dropping ’em on the floor and stamping on them. I think at a certain point, realizing that I’d destroyed so many fantastic guitars, I woke up one day and thought, “Uh, maybe I should just not do that anymore!” [Laughs]. It was kind of expensive. And so many guitars that I actually liked, but which were now beyond rescue.

“You know, I did this audition with Mick Jagger once. I don’t talk about this very much, so you’re probably the first person I’ve ever told.”

So that’s the Burns on Entertainment!?

No… Somebody in the north of England who made guitars made me a Strat copy, and I think that’s what I used on that record. I also had an Ibanez copy of an SG, and I loved that—that sounded really, really good. But that went the way of the other guitars. Sheer stupidity! It’s such bravado: “Who needs possessions, anyway? It’s just wood and metal. Fuck it!”

So many guitarists play Strats or Strat copies and make them sound really dull. I think you have to have a special, distinct style or approach to make them sound good.

That’s right. God knows, you can have a nice guitar, but it doesn’t really affect what you do with it… You know, I did this audition with Mick Jagger once.

What? Really?

Do you know about this one? I don’t talk about this very much, so you’re probably the first person I’ve ever told. He did an album called She’s the Boss—do you know that one?

Yeah, from 1985?

I think so, yeah. And Gang of Four had sort of stopped at that point; it was one of many hiatuses where Jon King said, “I don’t want to do this anymore!” So, I got this call from his management, “You want to come and play with Mick?” I thought, “Well, this could be interesting!”

And you’re a Stones fan from way back, right?

I am a Stones fan! I am, totally, totally. So I went down there, and it’s Jeff Beck, Mick, Omar Hakim on drums, and I forget who’s playing bass. Jeff Beck was really kind of sneery at me… he gave me the total cold-fish handshake. He was in the middle of an argument with Jagger when I walked in; I think they were having a very big argument about his role in this Jagger solo project.

Anyway, they were supposed to be doing a world tour, and Jagger was looking for a guitarist. We did some tunes, and they went fine, and then Mick goes, “So, Andy—d’you know how to play ‘Miss You’?” “Nope!” “D minor, A minor, G flat diminished 7th”—he reeled off all these chords, and I’m like, “I’m gonna really, really fuck up here!”

So we went into it, and just in time I started playing “Da da da da da-da-da!” Like, how the fuck did I do that? I was literally flying by the seat of my pants. But because I remembered a few chords, I was starting to get quite excited. And then we got to the solo, and Beck sort of leans back, about to go into it—and I was just like, “Fuck him,” because he’d been a bit of a knob to me, and I got in first and started playing the solo. And Jeff Beck dropped his hands and looked at me like, “You fucker!” [Laughs].

Anyway, the whole tour was cancelled, and they didn’t do anything. Jagger eventually toured Japan about a year later with Joe Satriani. But I had some fun out of it. And then I got home that night, I got back to my East End flat; I picked up the album that Mick’s management had sent me, and this piece of paper wafted out of the sleeve. I picked it up, and it said, “Oh yeah—can you please learn ‘Miss You’?” [Laughs.] FL

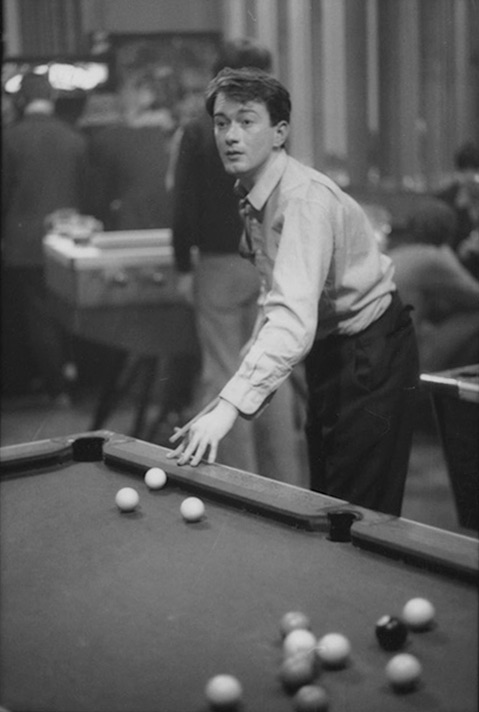

photo by Anton Corbijn