“It’s like going around the side door to someone’s unconscious,” muses keyboardist John Carroll Kirby. “When I go see a movie, people will say, ‘What do you think of the soundtrack?’ And 90 percent of the time, I’m like, ‘Shoot, I didn’t notice.’ If you hit people over the head with the big pop songs, that’s awesome, and I strive to do that at some point. But it’s also quite cool—maybe they don’t even know they’re listening to music.”

He’s reflecting on the concept of “background music,” a term that, given his jazz training and focus on tranquil instrumental textures, often prompts an “adverse reaction.” But he admits that some songs offer a specific, built-in functionality that a composer might not envision. “With my last full album, Tuscany, a lot of people tell me, ‘I’ve been putting it on first thing in the morning every morning,’ or, ‘I put it on at night when I’m trying to relax,’ or, ‘I put it on for my kids to help them relax.’ I find it very interesting that it could work its way into someone’s ritual.”

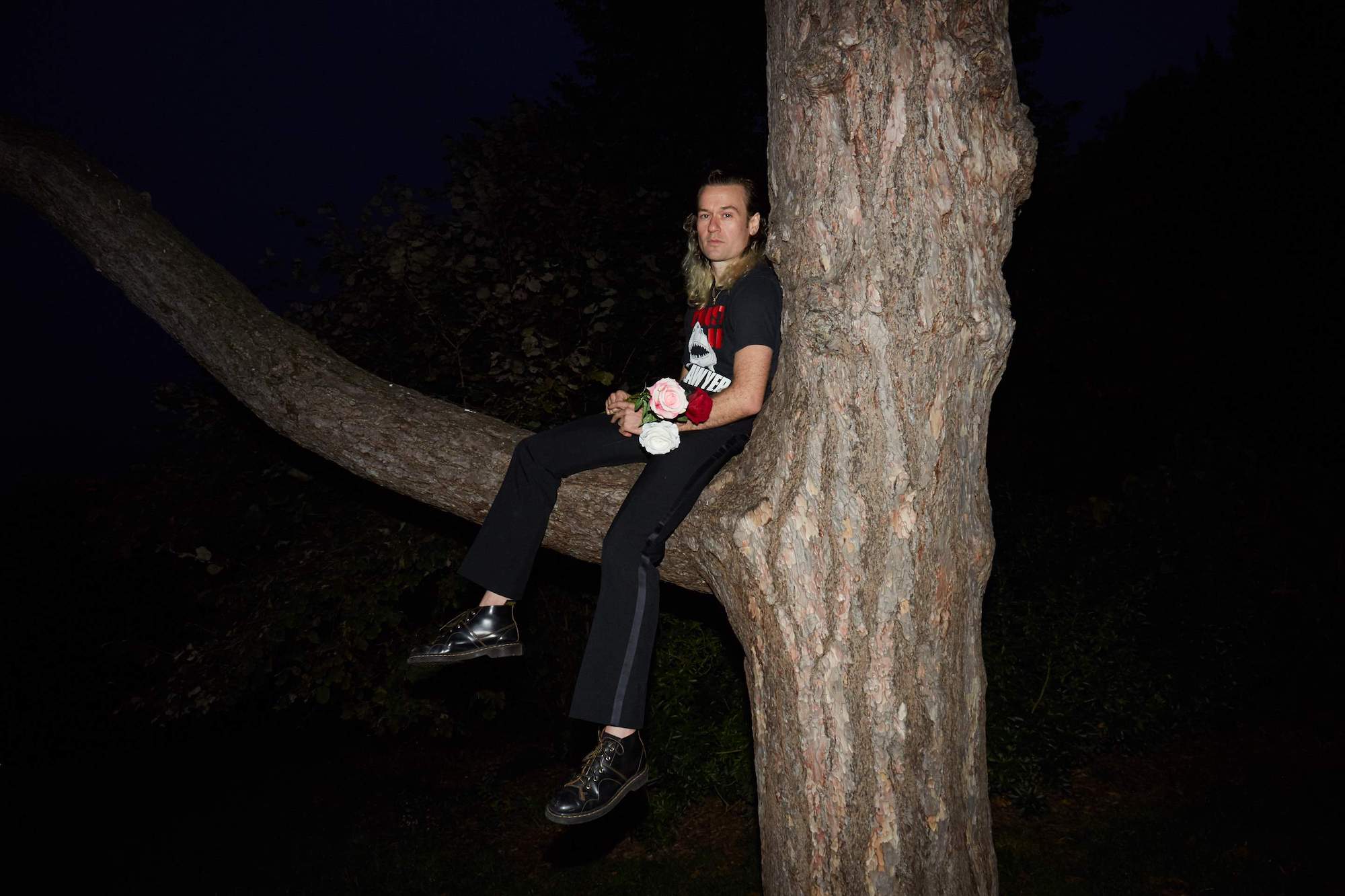

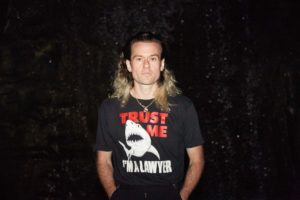

Kirby’s latest LP, My Garden—arriving just three weeks after his surprise-issued piano collection, Conflict—feels completely ritualistic. With its hybrid of soothing jazz-funk groove and futuristic new-age ambiance, it’s easy to picture these sounds billowing up like incense in meditation rooms and yoga studios. The album title even conjures a physical garden, where Kirby beckons you to breathe in the fresh air and wade through the flowers.

“It’s an invitation: ‘Come into my little zone,’” he explains. “A friend of mine said, ‘It feels very physical, like I’m stepping into your space,’ without knowing the title or any other story behind the record. That makes me think of those old ’8os educational videos where they shrink themselves and dive inside the human body, or like Honey, I Shrunk the Kids or something.”

Kirby’s garden path began in Los Angeles, where he studied big-band arranging and orchestrating with jazz double-bassist John Clayton, a former member of the Count Basie Orchestra and a composer/arranger for artists like Natalie Cole and Whitney Houston. But his career took a detour after he moved to New York around 2011 and slowly wormed his way into a community of like-minded artists.

“It’s an invitation: ‘Come into my little zone.’ A friend of mine said, ‘It feels very physical, like I’m stepping into your space,’ without knowing the title or any other story behind the record.”

One was his friend Aaron Pfenning, formerly of indie-pop act Chairlift, who recruited a then-emerging Solange Knowles to collaborate with the band Rewards. Kirby immediately vibed with the singer’s shapeshifting neo-soul energy, and that connection proved vital: A few years later, he wound up playing some keyboards on her commercial breakout LP, 2016’s A Seat at the Table, building his résumé and leading to other sessions with artists like Frank Ocean, Blood Orange, Kali Uchis, Harry Styles, and Bat for Lashes.

The keyboardist also took on new responsibilities for Solange: He co-produced a sizable chunk of her follow-up record, 2019’s When I Get Home, sharing credits with giants like Pharrell Williams and Metro Boomin. But Solange’s own influence looms largest on Kirby’s own musical approach, inspiring him to experiment with unorthodox techniques.

“She has a very wise and omniscient approach in the studio,” he says. “Sometimes she’d be like, ‘What are you hearing on this?’ And I’d do my thing. And other [songs], like on When I Get Home, were just straight-up jams in the room. Sometimes she would even use a chance music element. Often it would be me, her, and John Key, the other writer-producer on the sessions, and she’d say, ‘After eight bars, you guys are gonna play a new chord, but you’re not gonna tell the other person what that new chord is gonna be.’ It’s guaranteed to be a clash because no one knows what’s coming. We were deliberately randomizing things. I found that to be a really cool process.”

Solange’s anything-goes recording style also influenced Kirby’s solo career, which officially launched in 2017 with his debut LP, Travel. Throughout his catalog, the keyboardist nimbly blends lo- and hi-fi sounds, incorporating everything from iPhone piano recordings to polished samples and beats. His instinct is to just capture whatever take feels best, regardless of technical fidelity—and he’s intrigued by the middle ground between these sonic worlds.

“The only thing that steers people wrong when they’re recording is the idea that it has to be done a certain way,” he says. “I don’t want to give away too many of Solange’s techniques, but a lot of her keeper vocals were cut on a cheap mic, sitting on the couch, in a room with the monitors blaring. She’s not in a booth. She’s not using a fancy microphone. What helps is she’s an amazing singer. Seeing people do their thing allowed me to think, ‘The piano doesn’t have to be mic’d with six mics. In fact, that can cause problems—especially with piano, which has the tendency to sound overly earnest or overly authentic. A lot of times in music I’m trying to play with the completely authentic and completely inauthentic, or AI. I love to play with those things.”

“I don’t want to give away too many of Solange’s techniques, but a lot of her keeper vocals were cut on a cheap mic, sitting on the couch, in a room with the monitors blaring. She’s not in a booth. She’s not using a fancy microphone.”

My Garden is half human/half machine, blurring the line between live playing and programming and sampling. The meditative “By the Sea” builds on a breezy piano pattern with thumping percussion and the manipulated sample of a traditional Indian flute; the funkier “Blueberry Beads” pairs jazz piano stabs with washy synths and a simple, clattering beat.

The latter track also draws on Kirby’s spiritual side. Its title is a reference to the Rudraksha prayer beads that symbolize the playfulness of his guru, Sri Dharma Mittra, whom he met while living in New York. “I had a chance to look at a lot of different techniques,” he says. “At the forefront of everything he teaches is compassion. It’s real simple teachings, and he’s cool with all of them. I grew up with my grandma being very religious, and my dad reacted vehemently against that, and toward the later part of his life became a Satanist. I find there’s a lot of good stuff in Christian teachings and Hindu teachings and Islamic teachings. [Mittra] would just say, ‘I’m just telling you what someone told me. If this doesn’t sit with you, just take what you can from it.’ That spoke to me. It’s nice to be able to take a look at some of those things without feeling like you’re a part of a cult, or even a group, really.”

And that brings the conversation back to functional music—and how certain sounds seep in via unexpected routes.

“One of my biggest influences in jazz is the pianist Ahmad Jamal, who influenced Miles Davis and others,” Kirby says. “He often got labeled a ‘cocktail pianist,’ which I find a funny insult. Oftentimes when people hear instrumental music, they instantly think ‘movie soundtrack,’ which is fine. But I feel like there’s a way to actively listen to instrumental music. I don’t know what it is now, but people are inundated in content, and it feels like there’s been a shift in the past few years where we’re ready for something that’s not full-on stimulus. It’s cool to think of a different way to reach people.” FL