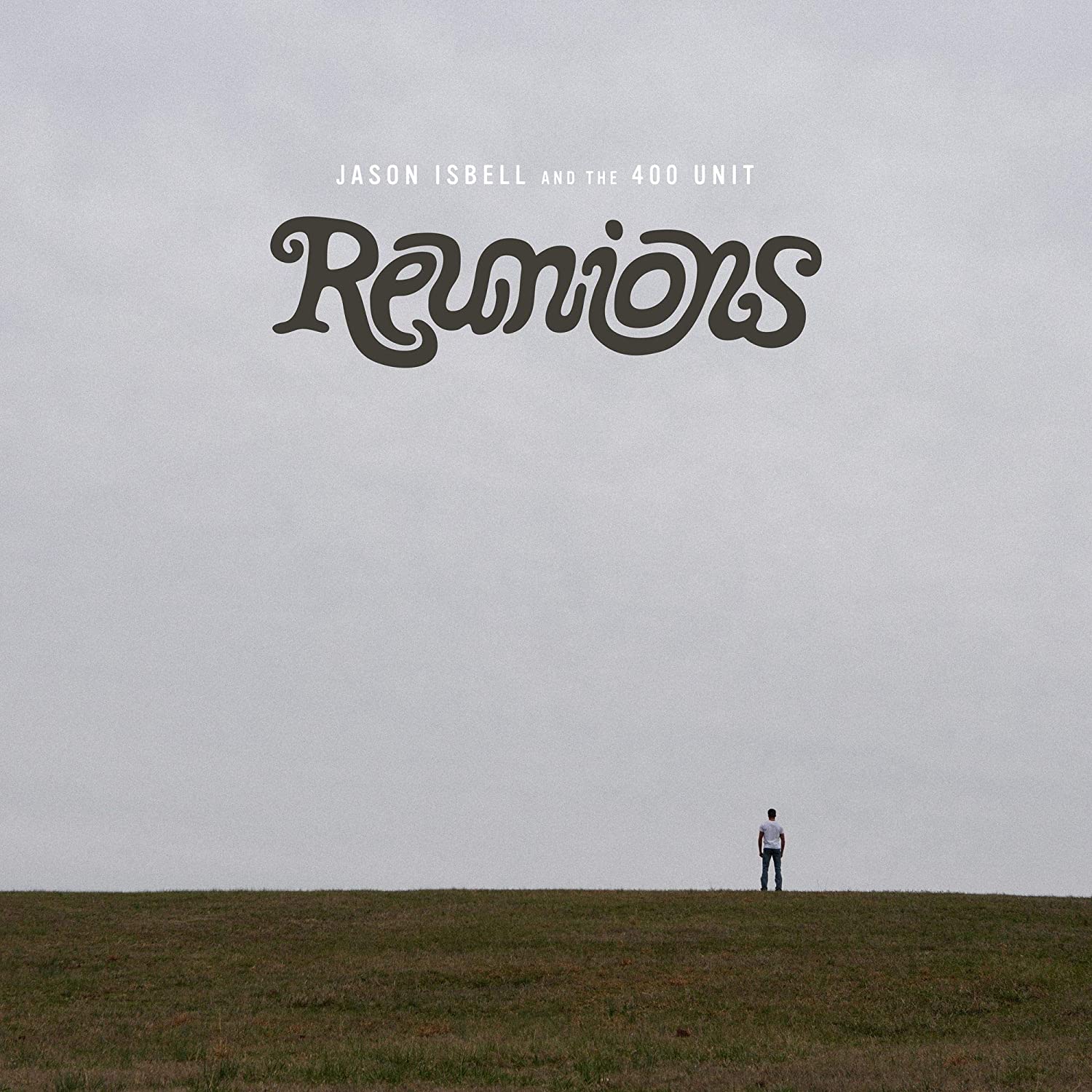

Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit

Reunions

SOUTHEASTERN

7/10

Jason Isbell is a star. It’s a weird thing to say, but it’s true—at least in so much as a country-tinged rock-and-roller can be a star in today’s day and age. When exactly that star was born is hard to say, but the process has been chugging along for some time. There’s plenty of evidence of his ascent—from his recent profiles in The New York Times and GQ, to his chief songwriting credit on A Star Is Born’s “Maybe It’s Time,” to, yes, his instigation of Twitter’s briefly popular feral hogs meme—but there’s no single moment.

Regardless of the when, the “how” lies in his unique ability to tell a story, both his own and those of his many tangled protagonists. But what happens when the teller becomes as noteworthy as the telling, and how does that shift our relationship with the stories themselves? Isbell’s new album Reunions may be his most personal yet, and while this can yield some of the record’s most hauntingly intimate moments, it can slip a little too far into preoccupied, essayistic memoir to be among Isbell’s best work.

This is brought out most starkly on the record’s topical songs, where theme and intention are far too apparent. There’s the protest song—the disappointingly trite “Be Afraid”—where a thesis of do-what-you’re-afraid-of isn’t so much nuanced dissertation as it is kitchen dressing kitsch. “What’ve I Done To Help” takes a similarly thin approach to guilt, the repetitive chorus only losing steam as the song progresses. Even songs that touch on such personal topics as Isbell’s relationship with his young daughter or much-discussed issues with alcoholism, while imbued with all the naked honesty and songwriting savvy we’ve come to expect, begin to feel overly obligatory.

Reunions works better when it exists in the vagaries, where the lines of fact and fiction mix and everything feels a little less predetermined. Take “Overseas,” a burner of a song, where specifics are blended so inseparably from obscurity that the point becomes moot. Whether it's one story or a collage of several is insignificant, all the explanation we need lies in the yearning slowly dripping from Isbell’s lead guitar. Even when his subjects become more precise, like on the nostalgia-laced one-two punch of “Dreamsicle” and “Only Children,” the obscured scope adds a layer of viscera where direct biographical facts could not.

This is not to say biography should be excised completely—how could I when the most arresting song on the record is so rooted in such moments of distinction? “St. Peter’s Autograph” is an understated song with a finger-picking style that’s just as much Bert Jansch as John Prine. Inspired by the death of a close friend of Amanda Shires—Isbell’s wife and collaborator—it’s prickly specificity is beautifully rendered, capturing a man at a loss but who reminds his lover, “I got arms and I got ears,” and desperately hopes that's enough. It’s a lullaby to a loved one whose features are fuzzy behind the film of a grief that’s impossible to share. It’s not quite like anything else in Isbell’s catalogue, or anyone else’s for that matter, and has far more staying power than anything more grand or pointed. In short, it’s what makes Isbell a star, and what will always keep us coming back.