America’s independent music clubs and theaters are at death’s door. Right now, there are no fewer than three bills in front of Congress, all of which could help the live music industry survive the catastrophic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Congress’s last day in session is August 7. The session could theoretically be extended, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has stated he will not do that.

The bills are designated as RESTART, Save Our Stages (a.k.a. “SOS”), and ENCORES (Entertainment New Credit Opportunity for Relief & Economic Sustainability). If none of them—or no Frankensteined combination or permutation—passes, is there another way that independent American music clubs can stay alive? A plan B?

That’s the question put to Dayna Frank of the Minneapolis venue First Avenue. She was on the phone last week, speaking not just for her own club but for nearly two thousand independent venues across the nation. Frank heads up a network of American clubs and theaters called the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA). It was formed in the wake of the massive March COVID-19-spawned shutdown. Its goal is to lobby Congress to find a way that would allow clubs to stay solvent as they generate exactly zero business now and for the foreseeable future.

Frank pauses before answering. “There are no other plans. We looked at it, we brainstormed and tried to come up with a plan B, C, or D, but no. There are ways to save individual venues, but this is a ten-billion-dollar problem and the only way to save the industry and ecosystem as a whole is through the federal government.”

Austin’s Barracuda, which shut down in June / photo by Daniel Cavazos

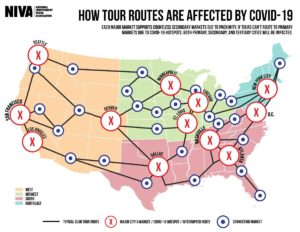

Look at it this way: Even if there is an effective and widespread vaccine available early next year—and audiences feel comfortable enough to mix and mingle in public—tours have to be planned and those bands need to have places to play. Yes, the clubs owned and/or booked by deep-pocketed promoting giants Live Nation and AEG may survive, but for the myriad clubs and theaters that aren’t part of those chains, if they’re shuttered, there’s no place for many of those bands to play, a catch-22.

Audrey Fix Schaefer, Communications Director for the 9:30 Club in Washington, and also a NIVA spokesperson, adds, “Like all other venues, we’re in a truly dire situation. Zero revenue and enormous overhead. There’s only so long we can hang on. No business is prepared for this no matter how successful you’ve been in the past. Without assistance we’re all going to fold. And this is why we’re fighting so hard.”

If none of these bills pass, says Christine Karayan, of LA’s fabled Troubadour, “We’re not going down without a dramatic fight. You will see bombs exploding.”

“We were doing well,” says J.J. Gonson, self-described “proprietrix” of the Somerville, MA club ONCE. “We’ve been closed four months and I’m afraid. I lie awake at night. What am I gonna do? Live Nation and AEG have the money to wait it out and all we’re gonna have is Live Nation and AEG. The world turned upside down and everything got handed to the bad guys. We’ve been inclusive and cooperative and caring of our community. Are we going to end up with nothing but corporate hands-off booking?”

It’s a situation that affects not just the venues, of course, but all those connected: the touring musicians, the crew, the staff, the caterers, the agents, the promoters, the communities in which the clubs are located, and those ancillary businesses. People who go to clubs also go to nearby restaurants.

“We’re a magnet for other economic activities,” says Schaefer. “People who come to a show have dinner before, or drinks afterwards. For every dollar spent on a ticket in a small venue, twelve dollars of economic activity is generated, considering the caterers for the act, other restaurants, transportation, and other things. The federal government assisting us is an investment—not just in keeping our industry from folding, but other businesses as well.”

“There are ways to save individual venues, but this is a ten-billion-dollar problem and the only way to save the industry and ecosystem as a whole is through the federal government.” —Dayna Frank, head of NIVA

“A million plus emails were sent to Congress,” she adds. “Hopefully, they’re taking note. It’s not a red or blue issue, but a green issue—helping business on main street USA. It is a fight for survival right now. No sugarcoating it, we are on the precipice if we don’t get this help.”

Cracker guitarist/singer Johnny Hickman has spent the better part of the last thirty-plus years of his life on the road, with his main band and in various other setups. “I’ve long gotten used to adjusting to change,” he says, “but we as an industry have never dealt with this ‘The parking brake is pulled, everything is at a standstill for the foreseeable future’ scenario. Buildings being sold, venues being torn down to make room for a freeway, a beloved club owner passing away or retiring, clubs being absorbed by big-gun entertainment conglomerates, these changes we know.

“Musicians, booking agencies, managers, and the fans themselves are all now faced with a mutual dilemma. The positive takeaway is that we all know this. If live music is going to survive COVID-19, we have to look out for one another and fight to acquire some help for the little guys. Though also adversely affected, the acts that play stadium-sized venues and those venues themselves have a better chance at long term survival. It’s the hundred-and-fifty to twelve hundred capacity small- and medium-sized clubs and the artists that rely on them that are the most vulnerable here. The passing of some of these proposed bills and grants is crucial.”

Tobi Parks is the owner and talent buyer at xBk in Des Moines, Iowa, a two-hundred-and-fifty–capacity club that opened last September. The name of the club stands for ex-Brooklyn, where Parks hailed from. She sunk her life savings into it. “If there’s not some kind of package, RESTART or SOS, or some combination, we will not survive,” she says “The other proposals out there [in front of Congress] don’t work for our industry. We’re not like restaurants that pop up and reopen. This could be years. We are the only industry that literally has zero revenue. I have to pay my mortgage, and the electric bill comes every month.”

“We’re going through the nest egg. I’ve shut off everything I can, but I’m still cranking out X amount of dollars a month in rent and insurance.” —Christine Karayan of LA’s Troubadour

The Troubadour, run by Karayan and in her family since the early ’80s, admits that because of the market they’re in—and because of the club’s visibility and prominence—they’re not in as bad a shape as some others. Nevertheless, “We’re going through the nest egg. I’ve shut off everything I can, but I’m still cranking out X amount of dollars a month in rent and insurance. We’re probably OK ’til the end of the year. We’re not glitzy and shiny. We’re smelly and kind of old—what you see is what you get, and a lot of people appreciate it for the familiarity of it.

“If [one of the bills] gets through, then, yes, it will be beyond a sense of relief,” she says. “You could, at that point, start to breathe. Unfortunately, with the other loans currently available, the structure doesn’t work for our type of business. I don’t know what day I can open the doors or when I can get up and running. Can I take on more debt than I have in place and drown myself?”

Michael Dorf, the CEO of the City Winery chain of small clubs, says frankly, “Not being able to put on a show is death. And the live industry is one of the only avenues for musicians to earn a living, an incredibly valuable aspect that is at risk of extinction. The world goes nuts when a bald eagle’s nest is disrupted during a construction project and I agree that’s important, but we’re talking about live music culture and it isn’t getting the attention.”

Dorf’s right. If you’re a musician, unless you’re topping the streaming or sales world, you’re making your living by touring. How much of your income? 75 percent? 90 percent? The Dream Syndicate’s singer-guitarist Steve Wynn laughs sarcastically. “Are you kidding? I’d say about 99.9999 percent from touring and the rest from sales and streaming.”

“I do most of my touring over in Europe and there is considerable relief funding over there for independent clubs, musicians, and other artists right now,” he continues. “Over here, it’s a different story. I hate to think of all the great clubs that I’ve enjoyed as a fan and as a touring musician that won’t stand a chance over here if this goes on much longer without some kind of assistance. It’s sad. They obviously understand the concepts of a quality of life and a more enlightened society in the old country, don’t they?”

Stiff Little Fingers singer/guitarist Jake Burns began his life on the rock road back in Belfast, Northern Ireland in the late ’70s and has lived in Chicago for many years. Before the pandemic, Stiff Little Fingers was touring a lot and had eight to ten European festival dates ahead of them. While a spring 2021 tour is being planned, everything is, of course, speculative.

“This is my job. If I don’t work, I don’t get paid,” says Burns, who says his band is in danger of hitting its endpoint. “Bob Geldof said this years ago: ‘Musicians make two types of money, more than you can ever imagine or not as much as you think.’ And he’s right. Private islands or working stiffs. There are very few bands in the middle ground. Royalties aren’t there anymore.”

In June, more than six hundred artists—Dave Grohl, Billie Eilish, Brittany Howard, Willie Nelson, Lady Gaga, Neil Young, and Leon Bridges among them—signed a letter sent to Congress saying, in part, “Independent venues give artists their start, often as the first stage most of us have played on. These venues were the first to close and will be the last to reopen… If these independent venues close forever, cities and towns across America will not only lose their cultural and entertainment hearts, but they will lose the engine that would otherwise be a driver of economic renewal for all the businesses that surround them.”

NIVA has gotten some TV attention. Jimmy Kimmel guest host Joel McHale chatted it up and bluegrass guitarist Billy Strings played from Nashville’s The Station Inn. Jimmy Fallon also plugged NIVA before segueing to Jimmy Buffett.

How optimistic or pessimistic are the club owners and musicians? My research over the past week suggests that everyone is on a see-saw.

“This is my job. If I don’t work, I don’t get paid. Bob Geldof said this years ago: ‘Musicians make two types of money, more than you can ever imagine or not as much as you think.’ And he’s right. Private islands or working stiffs. There are very few bands in the middle ground. Royalties aren’t there anymore.” —Jake Burns of Stiff Little Fingers

“I’ve swung the entire spectrum from reasonably optimistic to totally pessimistic,” says Burns.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” says Austen Bailey, talent buyer for the Mohawk Austin club in Texas. “But we’ve gotta use the phrase ‘You can’t perform a transplant on a dead body.’”

“It depends on what day of the week you’re asking me,” says the Troubadour’s Karayan.“Today, I’m a little more optimistic overall. This will end at some point. But there’s no way you can open at a quarter capacity and have it make any financial sense.”

On the one-to-ten scale—total pessimism a one and complete optimism a ten, Robert Mercurio, co-owner of New Orleans’ Tipitina, says, “My feelings of confidence go up and down. Today, I will say three. I watch the news and try to get a temperature of where Congress is at and it’s a real tossup.”

Mercurio is in a somewhat unique position, too: Not only does he co-own a club, he’s bassist for the funk-rock band Galactic. “We own the club and are stewards of this historic venue, one of the most storied venues in New Orleans and a big part in the history of our band. We’re a band so we’re doubly hit, struggling on both sides. It’s been extremely difficult. It’s not like we have another day job. We’re popular, but we can’t afford to take off that long.”

City Winery’s Dorf praises NIVA’s campaign—“extraordinary”—but “my opinion which is quite cynical right now, is I’m not that optimistic about our government. Fingers crossed, but I don’t see a magic program opening up in the next few weeks.”

“To be honest,” says Cracker’s Hickman, “my biggest fear is that as we’ve seen under the current administration, the ones at the top of the food chain, the one-percenters and the least vulnerable, will siphon off any and all of the proposed financial assistance. My hope is that the big-gun corporations who rely on alcohol and ticket sales will step in with some muscle and help us get these bills and grants green lighted before it’s too late. There’s my wounded, but unsinkable, optimism. I hope it’s as contagious as this horrible fucking virus.”

Then, Hickman addresses what might be the elephant in the room: Could there be negative sentiment that would kill these bills because right-wingers may hate entertainment “elites” and view rock clubs as such? That they, like President Donald Trump, consider art superfluous?

“Oh, absolutely,” Hickman says. “This is where the opposition will come from. The right wing traditionally operates from a place of fear or greed. If they can profit from it, they help. If not, fuck you, little club, little band. Fortunately, we have artists like Roger Waters and Taylor Swift on our side, calling out the filth and corruption of the soulless fascists currently at the helm.”

Frank differs, believing NIVA’s case is so strong it will transcend political bias. “It’s so blatantly obvious,” she says. “We are small intimate spaces where people sing and talk, and you have a virus that kills people in small intimate spaces primarily by singing and talking. You’d be hard-pressed to find an industry that needs aid more than we do, especially independents who have no ancillary revenue, no corporate parents, and no other ways of getting cash right now.”

If there’s a silver lining amidst these huge and hovering dark clouds, it’s been that NIVA has been able to organize all these disparate clubs into a network on short notice. While they were all dependent on each other to a degree—a band needs to route its tours by connecting with multiple venues—NIVA has put many of the players on the communicative playing field. Congressional action is on everyone’s mutual interest. Why has there never been an organization like this before? “We never had a need,” says Frank, “We’ve never been shut down on three-hour’s notice.”

“Instead of a loan—I hate to use the word ‘bailout,’ but it is going to be a lifeline. The government has provided similar support to other industries. Ours is a tiny drop in the bucket—we’re looking for ten billion dollars compared to hundreds of billions that were allocated to save banks and airlines.” —Tobi Parks of Des Moines’ xBk

The RESTART and ENCORES bills have been filed, and Save Our Stages, co-sponsored by Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) and Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), was introduced in the Senate last week, and was introduced on the House floor Monday, July 27, by Roger Williams (R-TX-15) and Peter Welch (D-VT-At large). For NIVA, it’s the preferred bill.

Schaefer explains RESTART as a loan program where a lot of it can be forgiven, with Save Our Stages being an out-and-out grant program. “Both have components that would fit our needs,” she says. “Congress negotiates what goes into the overall bill. This is when the sausage-making on the hill happens. I can’t predict what will happen, and people who’ve made law for the last twenty-five years cannot predict what will happen.”

“Save Our Stages is similar to RESTART in the way it identifies the business, but is more industry-specific,” says Parks of xBk. “Instead of a loan—I hate to use the word ‘bailout,’ but it is going to be a lifeline. The government has provided similar support to other industries. Ours is a tiny drop in the bucket—we’re looking for ten billion dollars compared to hundreds of billions that were allocated to save banks and airlines.”

I reached out via phone and email to various sponsors of the bills, hoping to probe their thoughts on the potential passing, only hearing back from U.S. Senator Michael Bennet (D-Colo.): “The forty-two Senators who have co-sponsored the RESTART Act demonstrates the overwhelming bipartisan support for the bill. Momentum continues to build with a wide cross-section of industries for this proposal as well—from concert venues to restaurants to hotels and manufacturing companies—because the hardest-hit businesses know it is tailored for their needs, and provides sustained support with flexible options for loan forgiveness and a reasonable amount of time to pay it back. If we want to prevent temporary job losses from turning in to permanent ones, and if we want to help the broader economy recover, we must include the RESTART Act in this next COVID-19 relief package.” FL