“I’ve never felt that, as artists, we should submit to the idea of, ‘Well, this is what you’ve done that’s working, so do more of that,’ or ‘This is what you’re known for, so do more of that,’” says Amon Tobin. “I think it should come from a place of, ‘This is what I’m interested in, and hopefully other people will be into it as well.’”

For about a decade now, the acclaimed Brazil-born, England-raised electronic composer has been slowly and studiously concocting multiple musical alter-egos, including the bass-driven Two Fingers and the punky, post-rockish Only Child Tyrant—both of which have released albums on Tobin’s Nomark label, which is also home to Tobin’s most recent recordings under his own name.

“It’s a bit of a mad idea, developing them all in parallel, but I’m taking it really seriously,” Tobin explains. “It’s not like they’re all little vanity projects. They’re all things that I’ve kind of touched on through various stages in my career, but have never fully explored; they feel very related, but they explore different avenues of sound that I’m really passionate about. I’ve sort of set the groundwork now, where I’ve got an album for each of these aliases, and I’ll continue to write for each alias as time goes on.”

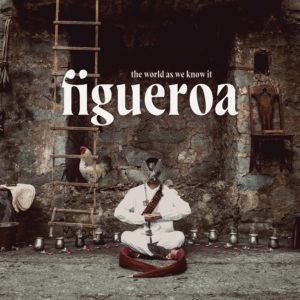

The latest addition to the Nomark roster (which also includes Stone Giants and Paperboy, two Tobin projects that have yet to be fully vetted for public consumption) is Figueroa, which might be Tobin’s most unusual and unexpected project to date. The World As We Know It, Figueroa’s debut album, is an intoxicating collection of dreamy psych-folk, whose eight songs all feature double-tracked, half-whispered vocals from Tobin himself.

While the album’s mellifluous vocal tracks were recently recorded by Sylvia Massy (Tool, Johnny Cash, Life of Agony) at Capitol Records in Hollywood, The World As We Know It was primarily recorded solo by Tobin nearly a decade ago in a secluded cabin in the woods of Nicasio, California. Though such a scenario typically conjures up images of a singer-songwriter strumming chords into a cassette recorder on an old acoustic guitar—and though songs like “Weather Girl,” “Put Me Under,” and the six-minute epic “Back to the Stars” all sound very guitar-driven indeed—the record is actually entirely guitar-free.

“It’s all programmed,” says Tobin. “I did everything with computers, so none of it is real, in terms of actual instruments. I’d done it all with MIDI, so I kind of made these really elaborately programmed picking phrases and chords. It would have been so much easier to learn how to play guitar, I’m sure of it [laughs]. But for some reason, I was like, ‘No, I’m an electronic musician—I’m going to do this electronically!’ It was innovation born out of necessity. I didn’t have the ability to play guitar, so I had to make do with what I did know how to do.”

In our chat, Tobin reveals the process behind the making of The World As We Know It, along with some of the elements (musical and otherwise) that influenced its creation.

The World As We Know It is certainly very different from anything you’ve done before—and the process of creating it seems to have been very different for you, as well.

Yeah, it was. I normally make instrumental music, and never really had any aspirations to any sort of vocal music. I mean, I’m certainly not qualified to do that, anyway, and certainly not guitar music…

I was living up in Northern California when I made the record. I was listening to a lot of Mexican radio and just driving around, listening to the sort of vocal harmonies that they were making, and trying to understand it a little bit. I was sort of exploring that in a really personal way with these recordings, and I really didn’t think about releasing them, ever. It was sort of a little experiment just for me.

It was kind of a weird time for me, as well. I was very isolated. I was drinking a lot of tequila [laughs]. Nothing was normal; it was not my normal set of circumstances or set of interests, or anything. All very different for me.

What motivated you to actually do something with these tracks?

I’d just kind of kept it in sketch form for years, in the background. And then I was going through hard drives and trying to organize things, and I found it again. My initial thought was, “These are good songs, and if they could be performed properly by someone who could play guitar and sing, they could be great! Maybe I could get someone to do this!”

I reached out to Sylvia Massy, and asked her, “Do you know anyone who might like to take these songs on?” Who knows—maybe some big star she knows would be into it, and I could help produce it or something? [Laughs.] But she got really excited about it, and kind of dragged me off to the studio at Capitol Records, and said, “Look, let’s just try and see where it goes.” She was very adamant about me giving it a go and trying to record it myself.

“Because I didn’t expect anybody to hear these songs, I was feeling very free to talk about whatever I wanted to talk about. I didn’t have the concern that it would make sense or mean anything in particular to anybody else.”

So I got more tequila [laughs], and she helped teach me things like how to stand, because I’d never sung into mics properly. She was like, “Don’t be hunching…this is how you breathe…” and just kind of gave me this crash course in recording vocals. I really don’t think I would have done it at all without her; she really gave me the confidence to try it.

Did you rewrite any of the lyrics for the final versions of the songs?

No, I didn’t, because I wanted an authentic representation of the songs. And I know a lot of it is nonsensical, and that a lot of the words aren’t very clear; but I want the feeling of the songs to be the priority, rather than the specific meaning. There’s something nice about ambiguity in music, anyway; people can contribute their own experiences to it, and not be too prescriptive about what it’s trying to say. I’m not trying to convey a message to anybody; I’m just trying to express things I feel.

Thinking about it now, I’m realizing that because I didn’t expect anybody to hear these songs, I was feeling very free to talk about whatever I wanted to talk about. I didn’t have the concern that it would make sense or mean anything in particular to anybody else. I was talking about very typical things—you know, love and death, the usual. But I think the songs ended up quite truthful, at least to me, about what I was feeling at that time. Heartbreak and paranoia, you know? Lots of dark thoughts that were fully explored just to see where they’d go. It was all done very freely, because I never imagined any of it going beyond my studio.

The name Figueroa—where does that come from?

It’s actually the street down the road from where I now live, which runs all the way through Los Angeles. But it also felt so Californian; it just tied in with the whole California experience for me. I was living up in Nicasio, which is pretty rural, and it felt like I was living in a Western most of the time.

“This music is like California through my own biased lens, very influenced by my probably not very accurate ideas about California, ones that had been constructed in my youth via road movies and all these popular culture tropes.”

Growing up in England, my references for California are all very cliched and romanticized—and I love that, you know? I love that these things sort of became real for me while I was here. So this music is like California through my own biased lens, very influenced by my probably not very accurate ideas about California, ones that had been constructed in my youth via road movies and all these popular culture tropes. But I don’t mind that. For me, it’s a very real experience, and it’s colored by all these references.

Were there any particular albums or movies that really implanted this romanticized idea of California in your brain?

Sure. I know half of Sergio Leone’s Westerns were shot in Italy, they still felt like California to me. And Byrds records, along with The Beach Boys, Mamas and Papas, and Jefferson Airplane—a lot of that sense of harmony and golden light, that golden edge to things that I felt all the way through this record. The Byrds, to me, are fantastic. Even just coming from a production background for me, I’m so enamored of the effortless production in those records, and the not trying hard aspect of it that’s just so disarming. I just feel like it sort of flows through you, that music, rather than accosts you.

I think a lot about how that kind of thing is achieved, and I always go back to imperfection and spontaneity. Coming from an electronic background, where everything is very contrived, you’re always shaping sounds and re-shaping them and considering every conceivable aspect of it and how it sits. And after [2011’s] ISAM—which was the record I’d made just before recording these songs—it felt so suffocating, almost, the competitive nature of that sort of production. You know, it has to cut through in a mix louder than everybody else, and every sound has to be the sound of the future; it has to be the most inventive and original thing…

There are songs on ISAM where people still don’t know how those sounds were made, and there is a sort of pride you take in making impossible noises and impossible combinations of sounds, where other producers are trying to work out how you did it. It’s really good, and it’s really interesting, but I don’t think that’s all there is to music. Making songs, the idea of doing guitar and vocal, just seemed so completely liberating. I’m not trying to reinvent the wheel; it’s just, “This is what I’m feeling right now.” And that’s what I needed to do at that moment. FL