It struck me watching the A&E doc Biography: I Want My MTV that while this is my nostalgia—an examination of a certain game-changing period for pop music—for many of you, this may be the ancient and somewhat unknown musical history of how rock videos changed the pop music world before the internet took over. This film, airing September 8 at 9 p.m. PST, premiered at Tribeca Film Festival in 2019 and was slated for SXSW this year. Then, you know, COVID-19…

The 90-minute documentary—directed by Tyler Measom and Patrick Waldrop—is a pretty deep dive into the early years. To wit: The radical idea of playing music videos 24/7 with VJ hosts, the challenge of getting the multiple local cable systems to add the channel to its mix, and the mid-’80s boom and massive influence on the mainstream tastes—as Sting says, “It made us stars, virtually overnight.” And then, when Warner-Amex sold it to Viacom in 1987, a short coda ruminating on the passing of the torch and/or the passing of an era.

Whatever MTV and its splinter channels are doing now, the MTV Awards still exist and Lady Gaga seems to be the Madonna of our time.

But what MTV did for pop music in the ’80s and ’90s, can’t be understated. It changed the paradigm of how pop got sold and consumed. How it got styled. Who got hot. Where the power lay. And it didn’t just change music: The quick-cutting oft-used in videos influenced commercials and movies as well—think Footloose and Top Gun.

MTV used free footage of the 1968 moon launch to kick off its programming, August 1, 1981 followed by the obvious first choice, The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star.” But then the cable transmission sputtered after that song—in effect, a deliciously ironic failure to launch—before resuming with VJ Mark Goodman.

Thing is, even if it had gone spectacularly, there were very few people who would or could have seen it. MTV had a product—a handful of rock videos, a few VJs, and a skeleton crew—but a very tenuous connection to its product being seen. John Lack, MTV co-founder, and his small crew had to head to a New Jersey bar to see the first broadcast; MTV was not even viewable in New York until a year and a half later. The same went for many other major cities.

It was, however, available on smaller cable systems across the country. Lack: “We brought pop culture to places that didn’t have pop culture.”

That struggle to get on cable, in fact, is where “I want my MTV!” comes in. It was a sly spinoff of the old TV ad where celebrities cried “I want my Maypo!” (a hot cereal for kids) and MTV’s version was created by the one of the guys on that team. There’s an engaging bit in the film about senior executive VP Les Garland flying to London trying to convince Mick Jagger to do it. Jagger wanted to get paid. He was offered a dollar. He took it. Once, the big guys signed on so did everybody else. The ad was aired on other networks, the pitch intended to convince young music fans to lobby cable companies to get the station on their lineup.

It worked. “They made the idea of MTV go viral before anybody really knew what viral was,” said rock writer Rob Tannenbaum.

In 2011, Craig Marks and Tannenbaum, veteran rock writers, published the highly regarded I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution. The two are frequent commentators in this film and the narrative hews pretty closely to their book.

There’s some good pre-history here, including the idea that The Beatles’ “A Hard Day’s Night” was really the first rock video and The Monkees’ TV show was, in effect, a series of rock videos. Mike Nesmith, in fact, is interviewed and talks about an earlier rock video show he created called PopClips for Nickelodeon, produced by Norman Lear. (PopClips aired Blondie’s “Dreaming.”) Nesmith was an early advisor to Lack, but declined the opportunity to join the venture. “I don’t want to be a television executive,” he said. “I don’t know where I fit in in all this, so I watched from the sideline.”

Lack was enthused about the concept, and brought in his programming friend Bob Pittman and later Garland, John Sykes, Gale Sparrow and Judy McGrath. “We had about 120 videos,” Sparrow said. “We would play anything that came through that door.” Even, yes, the Charlie Daniels Band.

The first five VJs—Goodman, Nina Blackwood, Martha Quinn, J.J. Jackson, and Alan Hunter—became stars, of a sort, themselves, and their scripted readings, flubs, and unscripted antics are featured here. But the most interesting part of I Want My MTV has a lot of behind-the-scenes stuff from the execs who ran the show back in the day.

When it began, of course, there were very few rock videos—who knew?—and bands that did have them, like Devo, benefited greatly. Singer Mark Mothersbaugh said the record company wanted to use promo money to make cardboard cutouts of the band for record stores. He said; “How about if we take the money and do videos?”

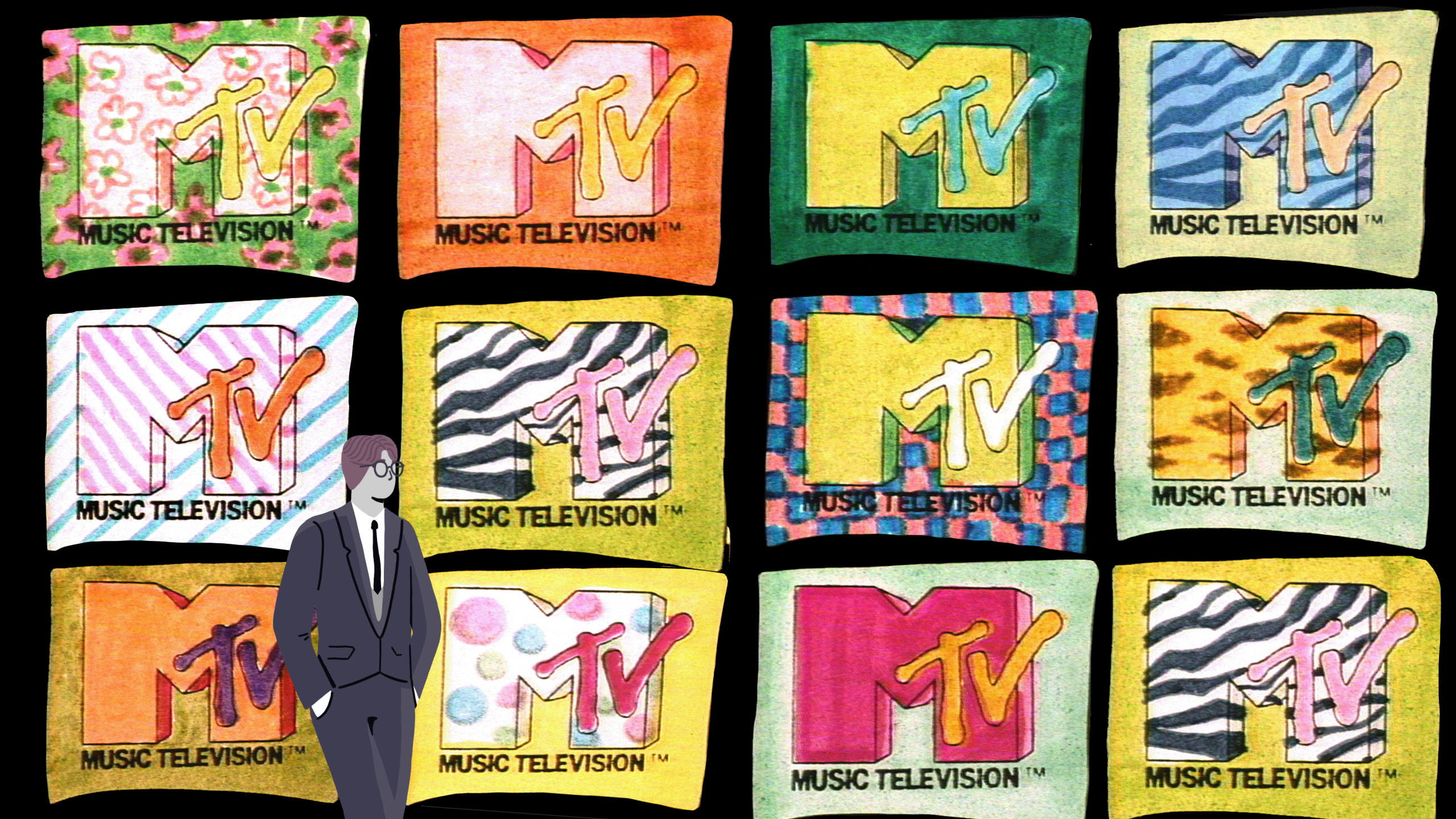

MTV staff circa-early-’80s

English new wave bands got a big bump, too. Rock on TV had been a staple in England for years, what with Top of the Pops and other shows. “We brought that punk attitude into MTV. We’d grown up with visual imagery being a part of music,” Billy Idol noted in the doc. “It was very much a second British Invasion spearheaded through MTV.” In short order bands like Culture Club, The Cure, Adam and the Ants, Bananarama, Duran Duran, and Eurythmics provided stylish, sexy, and, for the time, outré music videos. It wasn’t just enhanced performance clips; mini-narratives, often surreal, became part of the package.

“A lot of the British acts were making quirky, odd videos,” said Eurythmics guitarist Dave Stewart. “It was a portal or a platform into people’s living rooms,” added singer-partner Annie Lennox.

Inside the asylum, it was loads of fun. “We wanted to come to work,” said Lack. “There were parties, there was drugs, there was sex, there was rock ’n’ roll.” And paychecks to boot.

MTV’s initial programming idea was based on the concept of AOR (album-oriented rock) radio and, as such, was pretty much rock ’n’ roll made by white people for white people. (As MTV developed clout, AOR started taking its cues from the video channel.)

This whiteness did not go un-noticed in the culture at large, and it’s dealt with here. There’s a clip of Rick James saying, “We’re being sat in the back of the bus television style.” Fab 5 Freddy, later the first host of Yo! MTV Raps in 1987 said, “America was a country based on racist principles. It was kind of like television apartheid.” Lack called it “an early and disturbing chapter in MTV’s history.”

There’s a great interview clip with David Bowie from 1983—which was never aired—where he challenged Goodman about why MTV played so few Black artists. According to this doc, that was a pivotal point, and then along came Michael Jackson with “Billie Jean,” “Beat It,” and most spectacularly the long-form “The Making of ‘Thriller,’” which MTV sank money into (bending its stated policy of not funding videos, by saying it was making a doc about “Thriller”).

And, of course, there was the mega rap/rock breakthrough of Run-DMC. They’d done it on their own with three songs, but the cross-cultural clincher came with the duet with Aerosmith on “Walk This Way.”

In 1984, MTV debuted its Music Video Awards, featuring Madonna, singing “Like a Virgin,” crawling across the stage, wearing a bridal bustier, a wedding veil ensemble, and a Boy Toy belt. Yahoo music editor Lyndsey Parker called it “like our Beatles-on-Ed Sullivan moment.”

She also noted that the pre-MTV generation of artists woke up to the realities of the new video age. People like Billy Joel, Phil Collins, and ZZ Top who “couldn’t have been any less-MTV looking.” In fact, ZZ Top did a startling image revamp and became even bigger stars.

MTV did not wither after the sale to Viacom—not in my world. Some of the animated shows (Beavis and Butt-head, of course, but also Aeon Flux) were fantastic, and the two-hour Sunday night block of punk/new wave/alternative programming called 120 Minutes, hosted by Dave Kendall and Matt Pinfield, among others, was must-see TV. Of course, then came the cheesy reality shows like The Real World and Jersey Shore and when those kicked in, I left the premises. (Although The Osbournes was genius.)

I’m sure I was not missed by those charting the demographics. MTV always intended to skew young, and if this is what youth wanted to watch, so be it.

Whether it’s a nostalgia trip or a through-the-looking-glass revelation, I Want My MTV hits its marks. It was the upstart network that—for better or for worse—became the mainstream, changing the way pop music was played, presented, and consumed. FL