Tamara Saviano was supposed to be doing interviews like this one last year. She was supposed to head down to Austin, Texas for SXSW, where she would be premiering the film she co-directed, co-wrote, and co-produced, Without Getting Killed or Caught, a documentary based on the book she wrote about the late, great Guy Clark. Instead, as we’ve been reminded nearly every day for the past year, we all went home—movie theaters were shuttered, festivals were canceled, and the tragedy of the next year would clarify just how wrong the priorities of so many could be. After SXSW 2020 was cancelled, Saviano and her team (her husband, Paul Whitfield, co-directed the film) decided to postpone the film by an entire year, which, for Saviano, was a gut-punch, but the right way to honor Clark’s life.

Saviano is a Guy Clark expert, to put it mildly. The author, music producer, and filmmaker first fell in love with Clark’s music at the age of fourteen when she heard the opening chords of “Rita Ballou,” the first track from Clark’s sterling debut album, Old No. 1. In Texas, and in country circles everywhere, Clark is rightly celebrated as a legend. But Saviano has spent much of her adult life trying to tell as many people as possible about Clark’s genius ability as a songwriter and singer. As she says during our interview, “I don’t get how everyone in the world isn’t obsessed with him.”

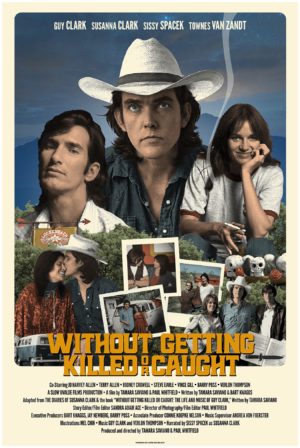

After writing Without Getting Killed or Caught, Saviano decided to adapt it into a documentary, using archival footage, photos, and a clever blend of mixed media to tell the story of Clark’s adult life. The narrative is told through the POV of Susanna Clark, Guy’s charming wife and a brilliant songwriter in her own right. Every time Guy and Susanna would gather with Townes Van Zandt, she’d bring out her tape recorder, and many of those conversations helped propel the story in Killed or Caught. The film’s momentum is sustained by talking-head interviews with Terry and Jo Harvey Allen, Steve Earle, and others. The film is a testament to the genius of Clark, and the passion of Saviano. Together, they tell quite a story.

The film was supposed to premiere at SXSW 2020. What was it like having to step back and wait for the right moment to put it out?

It turned out to be OK in the long run, as we didn’t finish the film until January of 2020, and we were set to world premiere on March 13. At the end of January we were doing our final audio mixing. So we were really in the trenches and I had been in the trenches on the Guy Clark story for many years because I did a tribute album, and then I wrote a book, and then the film. It was crushing, of course, when South By cancelled―not only for our film but for everything.

But having this year gave me a chance to catch my breath, and that has definitely been a silver lining. We decided pretty quickly not to go forward in 2020 and do anything else after South By, and then the other festivals we were going to do were cancelled in succession. We didn’t know how long the pandemic was going to last, or what was going to happen in the crazy election year. I just said, “Let’s just wait. Let’s just sit on it and wait.” I’m really happy that we did that, that we didn’t try to put it out last year.

“I didn’t care if this was neat and tidy, I wanted it to be honest. It was allowed to be honest because Guy opened up his entire life to me. I was over at his house digging through drawers and looking under the bed at his insistence.”

It’s probably disappointing not being able to premiere it at the theater, walk the red carpet, all that stuff. Have you adjusted your expectations and gotten used to the idea that it’ll be streamed from homes?

Yes, I have. Last year we had all these big parties planned, and I went shopping and bought all the outfits. But yes, I have adjusted my expectations. I love South by Southwest and this will be my 25th year, but just as an attendee. Immediately after South By we’re going to roll out six of our own virtual screenings with special guests at a $25 ticket price. Then we’re going to do something in-person outside in Austin, in May, and we’re going to do a theater tour later this year.

Because you’re so close to Guy’s story and that entire world, did you feel any pressure having to honor his story in the right way on film?

I didn’t feel any pressure in that regard because Guy was so open and honest about who he was. He was a flawed human being—and we all are—but some people like to make it more neat and tidy. I didn’t care if this was neat and tidy, I wanted it to be honest. It was allowed to be honest because Guy opened up his entire life to me. I was over at his house digging through drawers and looking under the bed at his insistence, “Go through everything in the house, do whatever you want to do.”

I felt like I had his permission to tell whatever story I felt was compelling. A lot of it is compelling, but what I found most compelling was Susanna and her take on everything, and the relationship between the three of them, Susanna, Guy, and Townes. That’s the direction I decided to go. I made the film I wanted to make, so let the chips fall where they may, I’m thrilled with the work we did.

I love the community of people you get to speak in the film. How early on did you know that this was the group of voices and artists that you wanted to get involved in the film?

Oh, pretty much from the start. The first work of [editor] Sandra Adair’s that I saw was her film that she directed, The Secret Life of Lance Letscher. And then I found out that she did [Richard] Linklater films. It’s a real gift that we got Sandra because she’s so busy with Linklater. But we met and talked about the film a couple of times. Terry and Jo Harvey Allen were amazing people to get, too.

It’s interesting, Guy was really sick for a long time. He had a long, slow, painful death—it was awful. And during that time he was in the nursing home for many months, and even at home he was struggling. All of his friends gathered around him, and during that time we were constantly in touch with each other. We were either sitting with Guy together or we were on the phone, filling each other in on his treatments, talking about how we could manage his pain. So I got to be close with all of the people in the film during that time. And I had interviewed all of them for my book, of course. So when it came time to having them tell their story on camera, I already had this really intimate relationship with them. I think that that helped in the way they come across in the film because they were comfortable.

It wasn’t just an unknown journalist filmmaker coming in from somewhere to interview them. It was me, who they’d been around for all these years in this really intimate, painful situation. They were all really tender with their interviews, tender about their feelings for Guy, and I think that intimacy comes across. I’m grateful to all of them, everybody. This was a big group project, everybody was generous, wonderful, and forthcoming. We were very lucky that we had that.

“When it came time to having them tell their story on camera, I already had this really intimate relationship with them. I think that that helped in the way they come across in the film because they were comfortable.”

What was the working relationship with you and Paul? How did you divide the filmmaking responsibilities?

Well, Paul and I are married and we’re still married, so it worked out. No, it was great. Paul’s day job is the video engineer in charge on Bruce Springsteen’s tour. So Paul has a very long career and deep experience in the technical side. He’s an audio engineer, he’s a video engineer, he’s an editor, he understands all the tech stuff. So all of that was his domain, and then he and Sandra collaborated on the editing.

I handled all the early storytelling on paper, I wrote the script with my friend Bart Knaggs, who I recruited to help me. I was the one who was in the trenches, finding all the images, setting up the interviews, doing the budget, and all that producer work. When we were actually shooting things, some of our film we shot, a lot of it is archival, but the beginning, the opening of the film with the VW van on the Natchez Trace, that’s all Paul.

For the archival stuff, because of my book, I was so familiar with what we had. When we would talk about a piece of the film, I’d say, “Oh, I think that photo would be perfect.” And then Susanna’s audio diaries are also a character in the film. Paul and I spent the entire summer of 2017 listening to those tapes after supper every night. I would pour myself a glass of wine and we’d sit in the living room and he had his gear set up, and we would digitize the tape as we listened. We would just go, “Oh my God, wow,” and I would take notes and write down time code, things like that. It was very collaborative in a lot of different ways, much more collaborative than writing a book.

How did Sissy Spacek get involved as narrator?

I am not a woo-woo person. I’m a pretty practical, pragmatic woman, but this was one of those lightning bolt things that happened. Paul and I were having breakfast at our favorite little pancake place in Nashville, Christmas of 2018, and we already had another narrator set, and we weren’t discussing the film, we weren’t talking about narrators, nothing, but all of a sudden I had this image in my mind of Sissy and I yelled out loud, “Sissy Spacek is Susanna! Sissy is Susanna.” And we’re in this restaurant, Paul’s looking at me like, “What are you yelling about?” And I said, “I’m just telling you, I know it, it’s got to be Sissy.” I was a fan of hers, especially Coal Miner’s Daughter, because I’m a country music fan, and I love her work, but I didn’t know much about her. So that day I went and bought her autobiography and I started reading it. And in that book, I found out that Sissy grew up a hundred miles away from Susanna Clark.

Sissy was in Quitman, Texas, Susanna was in Atlanta, Texas, so they’re both Northeast Texas girls. And then in that book, I learned that after Sissy won her Oscar for Coal Miner’s Daughter, she came to Nashville to record an album. Rodney Crowell produced the album, and on that album―I called Rodney right away since I read that on that album, she recorded a Susanna Clark song.

There obviously isn’t a ton of old archival footage in the film. Did you guys have to utilize the animation and mixed media because you didn’t have access to a ton of film from the old days?

Exactly. Guy’s family and Susanna’s family, they didn’t have archival footage like that. Guy and Susanna didn’t take pictures, it wasn’t like they were documenting everything that happened in their life. Particularly the scenes that are animated, which are really important scenes, capture a period when there weren’t any photos. The animator is a man named Mel Chin, and he was friends with Guy and Townes when Mel was a student at Vanderbilt University in the early ’70s. He had drawn these illustrations—some of them ended up in my book—that Guy would show people when they came to the house. They were illustrations of Guy, Townes, and Susanna. Since that time, Mel became a world-renowned artist, but I called him and I said, “Look, would you be willing to go back to that time and draw these sketches for us in that same style that you did when you were young?”

What is it about Guy that has made you dedicate so much of your creative life to him?

I’m such a big fan of Guy’s songwriting, and I just don’t understand why everybody in the world isn’t. I learned about Guy when I was fourteen years old, when I first heard “Rita Ballou” on the first track on his first album. I think he’s one of America’s best songwriters ever, and I want everybody to know that about him and I want everybody to be a Guy Clark fan. It’s really just that simple. FL