If you’ve been in the game long enough, there comes a point as an artist where you want to do things on your own terms. You don’t want to deal with jumping through hoops, talking to absent-minded execs or anyone who’ll try to influence your approach. You just want to put in your best effort toward the next project and see what comes of it. Despite joining up with Universal Music’s Canadian imprint, Toronto dance-punk act Death From Above 1979 got to push their compelling sound forward in their own way with their first release on the major label, Is 4 Lovers. This is also the first time they got to handle the production on their own music.

With their fourth album—and third since returning from a decade-long absence—out tomorrow, we sat down with drummer/vocalist Sebastien Grainger and bassist/pianist Jesse F. Keeler to talk about their personal attachment to the album, bringing more synths to the forefront, and their growth both as musicians and as people.

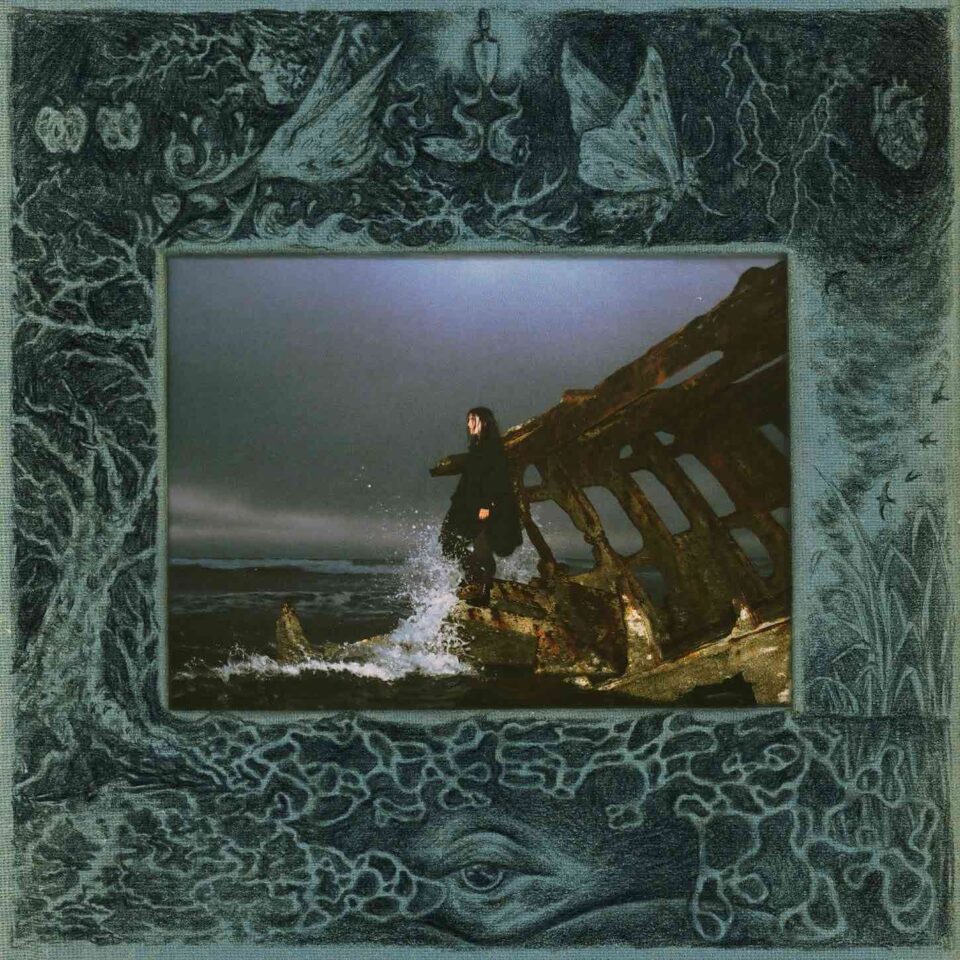

The cover for Is 4 Lovers is a vintage photo of an old couple embracing—is that a photo of either of your grandparents?

Sebastien Grainger: It’s a photo of my great aunt and uncle. My aunt passed away during the recording and writing of this record. I went to Chicago to go bury her and settle her affairs with my mom, and when we were in the house we found all of these incredible photos and love letters that my uncle wrote to my aunt. All that stuff had a very idyllic feel to it. Their marriage wasn’t perfect, yet the artifacts you can find of them indicate this kind of perfect life.

You don’t go through life without getting dirty, so for me it’s this perfect image of a couple in love. Under the surface there’s the regular complication of being a human operating in the world. It’s a personal statement, and the record, for me, both conceptually and lyrically, is a personal record, and I want it to reflect that. When Jesse and I first started playing together we played in a band called Femme Fatale which was essentially a solo project that he got a bunch of people to come play in. The record covers for that project were these very personal photos, so it’s kind of a throwback to that as well, where his personal history was part of the aesthetic.

What did you both want to do differently with this record? There seems to be more electronic elements at play in this one, were you trying to go for more of a dancy vibe?

“When we started we were a bass and drums band, now we’re just a band. That’s the stuff that we’ve used mainly, but we’ve used whatever to make the songs—whatever’s in front of us, we’ll figure it out.” — Jesse Keeler

Jesse Keeler: We made the whole record together in a room, which is different than what we’ve previously done. For the last record we wrote a whole bunch of songs, and when we got together we let the producer choose which songs we should continue and finish. This time we got together for five weeks, pretty much wrote a thing every day, and then with the stuff that inspired Sebastien we saw it through with the lyrics while changing things around. I want him to do whatever he has to do to what I’ve made in order to make him inspired to see it and finish it. I hate saying this because I love AC/DC, but I also use them as an example of what not to do in my head. Granted they nailed it the first time, but I don’t want to keep on doing the same thing all the time. We don’t want to make a record where the title can essentially be “More Death From Above.”

SG: I’ll also say that every record has had synthesizers, even from the very first EP. We’ve never shied away from that—the bands we’ve played in previously were heavy on synthesizers. I think more so than the last two, we were just trying to push those things out so that they’re more obvious instead of a synthesizer being in the background. It has more songs where the synthesizer or piano has a major presence. Jesse writes amazing things on piano, so it’s like, why wouldn’t we have more piano stuff? On the last record we included “Freeze Me,” which gave us the ability to do it live.

JK: When we started we were a bass and drums band, now we’re just a band. That’s the stuff that we’ve used mainly, but we’ve used whatever to make the songs—whatever’s in front of us, we’ll figure it out. Maybe it’s more about what the musical output of Sebastien and I together is that’s not really bound by the form anymore.

photo by Norman Wong

Did COVID play a role in the making of the record at all, or was the album made before the pandemic hit and you’ve been waiting for it to get pressed?

SG: Yeah, pretty much [the latter]. I’m so glad that it wasn’t written, at least lyrically, [before] this time because I would hate to have said something about this era and have to look back. It would have been too topical. We wrote the music in February and March of 2019, and then I spent the better part of that year writing the vocals and lyrics while finishing the songs and mixing. Then, around this time last year, we finished it and Jesse mastered it and we had it ready to go, but it was just really a timing thing of whether or not we wanted to put out a record in this kind of vacuum.

Going from the independent label Last Gang to this release with Universal, has anything changed in the way you’re being managed, the people you’re talking to?

SG: Last Gang was independent, but we were always working with major labels kind of in the background. Even the first record was put out through Last Gang, but it was also released through Vice and Atlantic, and the last two were put out through Warner Bros. in the United States. The difference this time around is we don’t have a history with the label, and there’s no precedent to the way we work together. We actually have complete autonomy—not like Last Gang ever infringed on anything, but they heard stuff early. Because we were kind of in this transition between labels, and because they’re a new label for us, we just made the record in complete autonomy. No one heard anything except for us. Until it was done and mastered, we were just like, “Here you go.” I guess that’s the opposite of what you would expect, but they gave us complete freedom and stayed out of our hair.

“It’s just the nature of the band at this point. We’ll do it ourselves and the label doesn’t have to worry about it.” — Sebastien Grainger

JK: It’s also a function of the fact that they know we’ve been around for quite a while, and they signed us with some inkling of what they were getting into. If a label sunk a bunch of money into a band that doesn’t have any sort of track record, the impulse to micromanage everything is much greater.

You know when you first start dating someone and you both kind of pretend that neither of you ever fart or go to the bathroom? It’s very much like that. You just don’t know about those things, and eventually that goes away. We’re in the “hiding farts” part of our relationship with Universal.

The music video for “One + One” was mostly filmed in a big field. Where was it filmed, and did you choose the setting out of necessity for social distancing?

JK: That’s at my farm. I’m also a farmer.

Wow, I didn’t know that.

SG: My wife made the video. She’s made some incredible videos for us already, so we had some ideas of what we wanted to do. She had some ideas as well, and in all honesty I’d rather do stuff with two or three people—I don’t love it when there’s a million people involved in anything. It’s certainly fun sometimes to make a big video, but in this case it’s circumstantial for sure. The label wanted to send people and we said, “It’s OK, you don’t have to send anyone. We’ll take care of it.”

JK: They did get upset at us because we didn’t tell them when we were making the video. They were like, “So what’s up with the video?” We told them that we were filming it when they called and they yelled, “We don’t have time to send someone! Oh no!”

SG: It’s just the nature of the band at this point. We’ll do it ourselves and the label doesn’t have to worry about it.

With Is 4 Lovers being your third album since reuniting in 2011, what would you say has changed the most between the both of you since reforming the band?

JK: Imagine when you were in high school and you were asked to write an essay. It seems so daunting at first—you have to form an argument, you have to have these multiple paragraphs of information. But now I could write a ten-page essay without a thought. At this point, there’s so much that we know now that we didn’t know before about making songs, about recording this stuff, about how to make things sound good, and about how to work with each other.

SG: There was also a little bit of imposter syndrome for me personally when we first started, because it was the first band I had sung in. When we blew up a little bit I always felt like I wasn’t ready. I didn’t feel ready to be that guy, I wanted to get better at songwriting, playing, and singing. I always felt like the snapshot happened too early, in a sense. I don’t regret any of it at this point, but in the moment I felt like I had to catch up. Now music, composition, production, and all that stuff is so integrated into our lives that there’s no real second thought about it. I know the type of music I make without Jesse, and I know the type of music I make with him. I couldn’t make Death From Above without him, and he couldn’t make it without me. We’re both so integral to what it is that it’s a non-issue, we just make and do. FL