By now, Black Midi is as close to a household name as a band not named King Crimson or King Gizzard can get while playing skronky fusion math rock. Before 2019, Geordie Greep (vocals, guitar), Morgan Simpson (drums), Cameron Picton (bass, vocals), and Matt Kwasniewski-Kelvin (guitar) were virtually unknown outside the UK, where their taut yet free-flowing live shows convinced a new generation of Brits that dudes can still occasionally rock. Their first streamable single went online that March, but by then they’d already played SXSW, signed to Rough Trade, and cut a vinyl-only LP with Dan Carey, whose track record includes work with Franz Ferdinand and Lily Allen.

This level of attention led cynics to rush to conclusions. The words “industry plant” slipped from poison pens—most of them stateside, as the band was quick to point out when I asked them for their thoughts on the charge. “Because it’s not on the internet, because it’s not in front of your eyes as an American, it didn’t exist until five minutes ago,” bassist Cameron Picton said, not without a trace of bitterness. But the initial wave of skepticism faded upon the release of Schlagenheim, the 43-minute dynamo of a debut they dropped that summer.

Less than two years later, they’re back with Cavalcade, a follow-up that leaves their first album in the dust. Where Schlagenheim was fast and loose, their sophomore record is carefully plotted. It retains all the bombast and unmitigated energy of its predecessor, but backs it up with compositions as virtuosic as their performers. Kwasniwski-Kelvin, on mental health leave from the band’s intense schedule, didn’t feature on the new album, and his towering guitar playing is missed, but the melee of instruments—horns, keys, organs, bouzoukis, and many more—in its place make for a more than satisfactory substitute. The mystique surrounding Black Midi’s dark magic still remains, but their foremost position at rock’s avant garde is no longer in dispute.

When I spoke with Cameron, Morgan, and Geordie earlier this month, they were in high spirits. Though they were all shacked up at their respective parents’ homes—they’re barely out of their teens, after all—there was new life in the air. Spring was springing in the soggy London streets, the COVID-19 pandemic was showing signs of retreat, and Black Midi was weeks away from releasing a strong album of the year contender.

The popular narrative is that you came out of the BRIT School fully formed, but there’s obviously more to it than that. What kind of music were you all making before you met?

Morgan Simpson: I grew up around music 24/7. My parents both play and teach as well. And I grew up playing in church, so every Sunday for me, from the age of five, was playing together with other musicians. The church I went to was Pentecostal. It wasn’t full-on massive gospel choirs, but you’re thrown into the deep end a lot of times. You really have to think on your feet, which is not that common in the secular world, where music is a profession, so you’re given a chance to prepare for things.

Geordie, you played in church too, right?

Geordie Greep: In secondary school, a guy a few years older who I played with asked me, “Do you wanna do this kind of stuff in church?” And I said, “Why not? A gig’s a gig.” I did that for most of my teenage years. There’s nothing quite like it. You have to play music that fits the substance of what the preacher is saying. You can’t play something too frivolous or showy. The music is a thing in and of itself; it’s not a business. It’s a really pure thing because you’re doing it for God, or whatever. That’s what music’s about: giving people joy.

“We used to say Talking Heads, Deerhoof, and Danny Brown were our three main reference points. But we were listening to very different kinds of music from what we were making at the time. So it was weird when we started hearing ourselves compared to bands we didn’t like or had never heard of.” —Cameron Picton

Cameron, how did you start playing?

Cameron Picton: We had a neighbor who was a guitar teacher, and my mom was a Spanish teacher. He had a daughter my age, so it was basically childcare: My mom would teach his daughter Spanish and he would teach me guitar. At school there were people who were good at instruments but weren’t into music, and there were people who were into music but weren’t good at instruments. I was making loads of recordings at home, but I wanted to play with other people, so that’s where BRIT came in.

What bands did you all bond over early on?

MS: One of our first conversations was about Mahavishnu Orchestra and Return to Forever—all that fusion stuff. I’d listened to some before that, but on the train journey home that night, I listened to The Inner Mounting Flame, and I was like, “What the fuck? This is so sick.”

CP: We used to say Talking Heads, Deerhoof, and Danny Brown were our three main reference points. But we were all listening to very different kinds of music from what we were making at the time. So it was weird when we started hearing ourselves compared to bands we didn’t like or had never heard of.

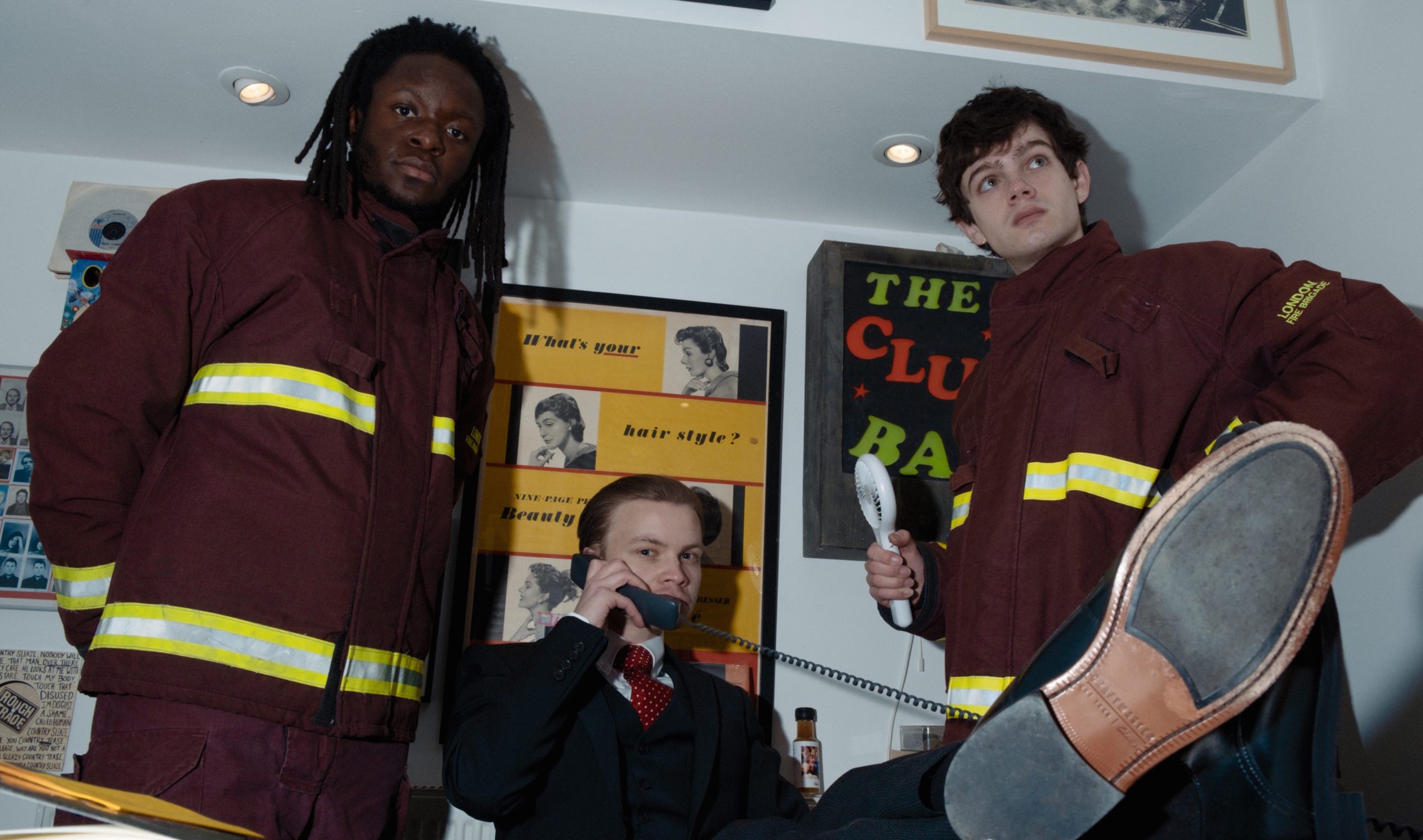

image courtesy of Anthrox Studio

The songs on Cavalcade are clearly more composed than the ones on Schlagenheim, which I understand came mostly from jam sessions. Can you walk me through the evolution in your process between the two albums?

GG: We were doing rehearsals for a long time where we’d all try to work out a song. We did that for the majority of the first album, and we were doing that for a long time to work on new stuff. But touring wears you down, and the material we got from these sessions was getting more and more bland. We’d leave the rehearsal room with an idea, but nothing else, really. That went on for like a year until eventually we started bringing in complete songs and learning to play them together. It became a more interesting way of doing things.

MS: The notion that the whole first record was improvised…I don’t know how that came about, but it’s not true. It’s just that the creative process of the songs that were on that record involved more improvisation than this time around. It was a natural progression.

“This time around, we were all very clear that we wanted to have more colors and tones, a broader palette of sounds. The first record was claustrophobic, and the music lent itself to that, but it didn’t make sense to go that same direction this time.” —Morgan Simpson

Dan Carey, who produced Schlagenheim, has a very different discography than that of John Murphy, who you worked with on Cavalcade. How was working with each producer different, and why did each of them make sense for where you were at when you recorded the two albums?

MS: When we went into the studio with Dan, we were at a point where we played the songs a certain way because we’d played them live so many times that year. It was impossible to get out of that routine and shape the songs in a different way. Dan was able to be the outside voice and make final calls. We didn’t have a good idea of what we wanted to do in the studio, so we needed someone like that to collect all of our ideas and make decisions for us. But this time around, we were all very clear that we wanted to have more colors and tones, a broader palette of sounds. The first record was claustrophobic, and the music lent itself to that, but it didn’t make sense to go that same direction this time. That’s a big pillar of our band: to always keep things moving and fresh. On Cavalcade, we’re credited as co-producers. We had one or two days of post-production after we tracked everything. We’d thrown everything onto the canvas, and we used that time to strip it all away and form the songs into what they are now.

There were lots of new musicians on Cavalcade who weren’t on Schlagenheim. Was that always the plan, or was it partly due to Matt leaving the band?

GG: The material just warranted it. These are melodic songs, expansive songs, dynamic songs, songs with difficult parts and crazy chords. Usually we can have a go at playing the piano, or some other funny instrument. But we wanted real virtuosos this time. It means that once we get back to doing the live shows, the task of replicating this album exactly will be impossible. It’s gonna be a fun challenge, and it’s good for the audience: They won’t have to go to a live show that’s exactly the same as the recording.

Geordie, looking at the album credits, you still ended up playing about 10 different instruments on most tracks. Did you have all of your gear in mind when you wrote the songs, or did a lot of it come from messing around with what was in the studio?

GG: On some songs, when we were doing them at home, I was adding guitars, slide guitars, accordions. But when we got in the studio, whenever we had an idea, we’d just set it up and record. I’d never played an organ before, really, but they had one there, so we used it. Cameron played an upright bass on a few tracks. The philosophy was that if it sounds good in your head, it’ll probably sound good in real life. And if it doesn’t, nothing to lose.

“Once we get back to doing the live shows, the task of replicating this album exactly will be impossible. It’s gonna be a fun challenge, and it’s good for the audience: They won’t have to go to a live show that’s exactly the same as the recording.” —Geordie Greep

Morgan, you used some pretty unorthodox objects as percussion on this album. What were some of your most exciting finds in the studio that made it onto the record?

MS: Definitely the wok [laughs]. And there was also a salt shaker that absolutely blew my mind; it sounded sick.

Cameron, what’s a Marxophone?

CP: It’s a zither type of instrument that was at the London studio. It has a cool sound, but it wasn’t one of the main instruments we used. A lot of the extra ones that we’re playing ended up just being textural. The other ones I liked were the two bouzoukis we used on a couple tracks.

I understand each track on the album is supposed to represent one of a “cavalcade” of characters. The first two, “John L” and “Marlene Dietrich,” are pretty straightforward. Can you introduce some of the other characters on the record?

CP: “Slow” is about a young, idealistic revolutionary who gets shot in the head after a counter-revolution, and “Diamond Stuff” is someone who dies and goes through the process of becoming a diamond, and then they get mined at the end.

GG: “Hogwash and Balderdash,” that’s two funny guys—in the vein of Asterix and Obelix or Bouvard and Pécuchet or The Defiant Ones—getting up to mischief. “Dethroned” is about someone who’s just done something unspeakable. And the last track, “Ascending Forth,” is one man’s journey to be reborn.

Up to that last track, the sequencing feels very intentional. Did you spend a lot of time on it?

GG: It took, like, five minutes, if I remember. The harder thing was deciding which tracks would go on the album and which wouldn’t. There were a couple, like that track “Despair,” that didn’t make it. But I think we ended up making the right decisions. You can’t really start off with “Ascending Forth,” can you? And you can’t really have a track like “John L” in the middle or right at the end.

“Ascending Forth” does feel pretty removed from the rest of the album. It starts off very slow and dramatic and silly, with the repetition of “Everyone loves ascending fourths.” Do ascending fourths have a special meaning to you? Are they your favorite intervals?

GG: It’s just one of those things that’s in all music. It’s cheesy stuff, and you can be that guy who doesn’t do the clichés, but you know what? They’re clichés for a reason, buddy. Sometimes you’ve gotta just jump on and ride the train to Cliché Canyon. FL