In the early 2000s, Wire cultivated a creative process that can never be repeated. Though this era is bookmarked by the end of the iconoclastic U.K. post-punk band’s original incarnation, it includes a series of releases that are unique to their discography, drawing on the quartet’s contemporary interests in dance music, industrial, and metal. A new compilation, the double 10-inch P456 Deluxe, collects the definitive version of Wire’s output from 2001-2003, making several titles available in full on vinyl for the first time.

Following their electronica-speckled 1990 album Manscape, Wire’s members shifted their focus toward individual pursuits. Singer/guitarist Colin Newman and his wife Malka Spigel of Israeli post-punk group Minimal Compact launched the label swim~, drifting into the uncharted waters of ambient music and techno. Bassist Graham Lewis moved to Uppsala, Sweden and worked on various projects as he explored the Scandinavian metal scene. For several years, drummer Robert “Gotobed” Grey left music behind altogether. Yet guitarist Bruce Gilbert’s work during this era is likely the most experimental, with guises including DJ Beekeeper—a project that found him performing in a garden shed while blindly selecting tracks from CDs spray painted black.

When Wire reunited for a performance at London’s Royal Festival Hall in the year 2000, alongside an American tour and an appearance at All Tomorrow’s Parties, it ended a nearly decade-long hiatus. “I was very, very nervous,” Gilbert remembers with a pained laugh. “I suppose the rehearsals were quite fun, but I was completely shattered by the actual shows. It was mostly because I was so nervous about having to relearn how to play the guitar, which I was never much good at anyway.”

As they returned home for a residency at London venue The Garage, Newman began recording Wire’s sets. Using one of their most beloved songs from the late 1970s as a building block, he transformed “12XU” into a pair of experimental remixes, imagining “what it would sound like if Fatboy Slim made punk rock records.” Beyond giving the other three members a hearty laugh, this sampling and resequencing approach became the basis for a new form of composition. With Grey’s drums already recorded, and Lewis sending over his bass parts while remaining in Sweden, Newman and Gilbert became the band’s primary architects.

“During that period, Bruce came over to my home studio two or three times a week,” Newman explains. “The process was nebulous, but I realized early on that we had hit on something. Even though we had something in common as guitarists, we didn’t necessarily get on with each other. Working together in this way, we discovered that we had complementary skills and were capable of giving each other the space to get along with what we needed to do. Going into it with zero expectations helped us, too.”

“What I’ve learned over the years is that it doesn’t pay to over-interpret Bruce. Taking things completely literally is a style of comedy we enjoy that also has a certain beauty to it.” — Colin Newman

Since their groundbreaking 1977 debut album Pink Flag, Wire have maintained a steadfast belief that less is more. A formative manifesto written by the group in that year includes various rules such as “no solos,” “no rocking out,” and “when the words run out, it stops.” This minimalist modus operandi was carried into the early aughts with “In the Art of Stopping,” the song that opens both 2002’s Read & Burn 01 EP and the new compilation. When it came time for Newman to add lyrics, he reached for a note left in the studio by Gilbert that simply read “trust me, believe me, it’s all in the art of stopping.” In a trademark example of the singer’s slyly absurdist humor, these 11 words were stretched across the song’s entire 3:35 duration.

“That note could be a rather bleak commentary on Wire, or Bruce’s relationship with the band,” Newman laughs. “Or it could just be the fact that the song has a lot of stops. What I’ve learned over the years is that it doesn’t pay to over-interpret Bruce. Taking things completely literally is a style of comedy we enjoy that also has a certain beauty to it.”

As P456 Deluxe unfolds across four sides of 10-inch vinyl, the guitars grind and churn with an industrial abrasion, while Grey’s heavily processed drums keep time with robotic punk precision. “Comet” barrels forward at a frenetic pace as the lyrics written by Gilbert once again become a self-conscious meta-commentary: “And the chorus goes / B-b-b-b-bang / Then a whimper.” Elsewhere, Newman’s pissed-off sloganeering is reminiscent of Dutch anarcho-punks The Ex, while his shout-rap delivery on “Spent” sounds like a precursor to Sleaford Mods. The laundry list of clipped, rhyming phrases that propel “Raft Ants” (“Tim Roth, Tiger Moth, altar cloth, dot.com froth”) take a similar lyrical approach to Wire’s 1988 pop hit “Kidney Bingos,” but could also be mistaken for a piss-take on Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start The Fire.”

The relentless thump of “Half Eaten” features a melody that bizarrely recalls “The Name Game,” yet its lyrics are far more bleak than anything Shirley Ellis could have turned into a fe-fi-fo-nana nursery rhyme. In under two minutes, Gilbert’s ominously slurred vocals describe a state of environmental devastation where even God can’t save us: “The temperature is rising / It isn’t surprising / The fires are everywhere / There won’t be any water.” “I’m pretty disappointed in the human race, so that’s bound to come out in my lyrics,” Gilbert says. “Of course there has to be humor as well. Having that makes the pessimism even more exaggerated and poignant.”

Throughout the course of a singular career, few bands have evolved as rapidly and radically as Wire. In the span of their first three albums alone, the quartet showcased the pipeline from punk to post-punk, before transitioning into left-field synth-pop in the 1980s, then burgeoning forms of big beat electronica in the ’90s. Needless to say, after their first quarter-century of musical metamorposis leading up to the period documented on P456 Deluxe, Wire were keen to continue swimming against the tide. “Rock devalued itself in the ’90s,” says Newman. “With the rise of Britpop, indie bands became mainstream. It wasn’t just something you read about in music magazines; you could read about it in normal magazines. People from Blur and Oasis were famous. None of it seemed very interesting to me.

“People seem to discover things for the first time after 20 years. In the end, we just decided that these recordings deserved to be heard. I’m quite proud of them, but that’s not always a good sign!” — Bruce Gilbert

“What was great about dance music in that era was that it was kind of faceless,” he continues. “You didn’t know what anyone looked like, or whether they were even Black or white. That was an area where Bruce and I could hit it off because he’s never been driven by fame. We enjoyed the fact that we were using elements of dance music and rock music to create a new hybrid that didn’t exist.”

Newman acknowledges that Wire weren’t alone in their electronic fusions of the early 2000s, but is quick to mention his distaste for the band’s peers. “There were other artists using guitars and beats back then, but that was more like indie trip-hop,” he says. “It was mainly just horrible.” Even within Wire itself, the singer has never shared bassist Lewis’s interest in metal, or believed it impacted their sound in this era. “Dance music with pummeling tempos could draw some comparisons to metal, but I don’t like it personally,” Newman shrugs. “Heavy metal is for 14-year-olds, as far as I’m concerned. It’s the most safe, conformist style of music you can get.”

These kinds of creative disagreements, coupled with feelings of exhaustion, led to Gilbert’s departure from the band in 2004. “I got very fed up with touring and just needed a rest,” he says. “Things like festivals were a nightmare in the end. We would turn up in the morning for a sound check and then have to stooge around until midnight or even later until we got on stage. Of course that meant avoiding drinking and not being relaxed enough to enjoy reading a book.”

“What was great about dance music in that era was that it was kind of faceless. You didn’t know what anyone looked like, or whether they were even Black or white. That was an area where Bruce and I could hit it off because he’s never been driven by fame.” — Colin Newman

Wire have continued without Gilbert—first replacing him with Liz Phair guitarist Margaret Fiedler McGinnis and more recently Matthew Simms—but this final period of studio collaboration is a fitting culmination of the band’s founding line-up. Gilbert’s buzzsaw riffs and bitter lyrical fixations are featured heavily throughout the songs of P456 Deluxe, immortalizing a late-period apex from two decades ago. “People seem to discover things for the first time after 20 years,” says Gilbert. “In the end, we just decided that these recordings deserved to be heard. I’m quite proud of them, but that’s not always a good sign!”

Newman agrees that this era of Wire has been unfairly overlooked. With their inability to tour during the pandemic, the time became ripe for an archival release. He shares a few gripes about Record Store Day, but is thankful for the opportunity to support brick and mortar music shops, while exposing new listeners to the band’s rewired rock sound of the early 2000s.

“Malka and I have barely been out of Brighton for the past 12 months, so the idea of the band getting together to do anything was very unlikely,” Newman concludes. “There are lots of annoying things about Record Store Day, but we decided to do a special project this year. If you want something that defines a Record Store Day release, forget your Bruce Springsteen on purple vinyl and get this instead.” FL

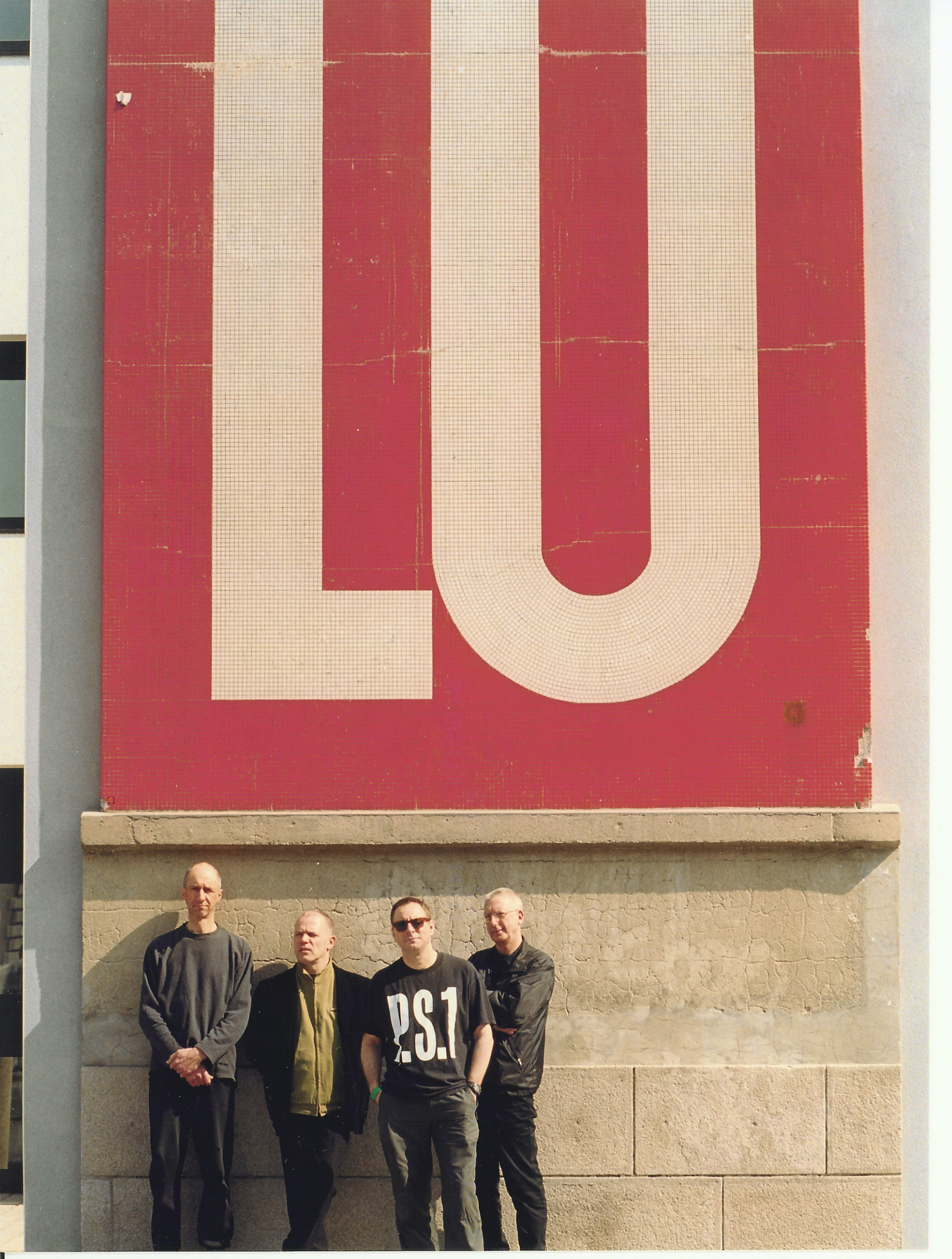

Photo by Phil Journe