Gordon Gano isn’t big on anniversaries, but the Violent Femmes frontman is willing to make an exception for the band’s 40th birthday. It’s hard to believe their self-titled debut was released in 1983, since songs such as “Add It Up” and “Gone Daddy Gone” are still indie staples that combine elements of folk and punk rock into a unique amalgam that still hasn’t been replicated. Then there’s the album opener “Blister in the Sun,” a song that was never intended to be a single yet has taken on a life of its own over the past four decades.

To celebrate, the band is revealing an animated video today for the song, which celebrates the track in all of its demented glory. In addition to the new video, the band recently reissued their long out-of-print greatest hits collection Add It Up (1981-1993) through Craft Recordings, although good luck finding one of the limited colored vinyl editions as those sold out instantly.

We caught up with Gano on the eve of this anniversary to discuss why time is just a construct, the genesis of “Blister in the Sun,” and what it was like singing karaoke to his own band. We also talked about the unique space that the Violent Femmes exist in and what it’s like being in a band that everyone knows, yet few people may actually recognize on the street. As you’ll see from this interview, that’s just the way Gano likes it.

At this point, “Blister in the Sun” is such a big part of the cultural fabric. Why did you think the band’s 40th anniversary was the right time to release a video for the song?

It makes sense to have a special release for it because one thing that would surprise most people is that it was never a single from the album. It wasn’t the track that everyone was thinking “Oh, this is going to be this great song that everyone is going to love.” We felt strongly about it, we would start shows playing it and we put it first on the album, but it wasn’t picked to be a single or have a video for it, so it makes sense to address that—and people like anniversaries, especially ones that end in a zero or five.

Like you said, the song wasn’t an instant hit. Was there a moment when you realized “Blister in the Sun” was such a phenomenon?

There are a couple of things I can recall—I’m not sure the exact timing of them, but one was at a baseball game where it was played briefly. I had heard that it had happened, or I had heard it once on television, but to be in the stadium, to hear it, was certainly something I never would have imagined. It was also a little amusing that everyone was there for the baseball game and they were totally unimpressed and ignored that my song was just playing. [Laughs.] That was kind of funny, the apathy. I’ve heard about various sports teams who will play it in their arenas or warm up to it as part of their mix. Someone told me a story of an athlete who won medals skiing in the Olympics and told us that they always listened to one of our tunes before they started their run.

“‘Blister in the Sun’ was never even a single, there was no video done for it, and yet somehow it became this classic song that now generations have really liked, to the degree where people who didn’t know the name ‘Violent Femmes’ were familiar with the song.”

It also seemed like the song’s rise happened so organically and in a way that I’m not sure could happen today.

Absolutely, completely. Like I said, it was never even a single, there was no video done for it, and yet somehow it became this classic song that now generations have really liked, to the degree where people who didn’t know the name “Violent Femmes” [were familiar with the song]. I played in a band called Gordon Gano and the Ryan Brothers—we have one album out called Under the Sun—and one time someone requested it or something, so I sang “Blister in the Sun” with this other group and I heard someone say in this small club/bar setting, “I love this song, this guy sounds pretty good!”

As another little aside, there was one time where I did karaoke and I was so surprised to see that there were some Violent Femmes songs, so I did a couple of tunes and got a moderately warm response. [Laughs.] Nobody thought anything of it, but it was really strange and really fun—and now that I’ve don’t that, I don’t have to do it ever again.

We discussed that in some ways, anniversaries can be a construct, but 40 years is still a long time. What does it feel like at this stage in your life celebrating these songs you wrote as a teenager?

Well, it’s not what I would have expected, because the world isn’t what anyone expected with the pandemic and not doing any tours; I think it would be a whole different thing being on tour and engaging with it in that way. Time is a strange thing. It doesn’t feel that long, really, and yet it is quite a stretch. I’m personally disassociated from these things. Earlier this year when I saw something written about things being done to celebrate the 40th anniversary, my first reaction was “40th anniversary of what?” And then I thought,“Oh yeah, the band.”

Whenever we play, it’s really in that moment and so the songs never feel old. They always have a freshness because of this, and because of the audience and the response and the reactions and also because of our approach. We don’t try to have an ideal way in mind that we’re always trying to duplicate: The tempo will be slightly different, just being human beings. We don’t play locked into a certain time, so some days we might play it a little faster, some days it’s a little slower. We also always have this sense of constant improvisation, even if most of it would not be noticeable to somebody who isn’t actually a part of doing it in the moment. I’m aware of what I was thinking and feeling when I wrote a song, but it’s not like the song makes me think of that; it kind of is a fluid thing, songs and lyrics.

The Violent Femmes are unique in the fact that you have both commercial success as well as credibility. Someone who doesn’t really listen to music probably knows about the Violent Femmes. How does it feel to exist in such a unique space?

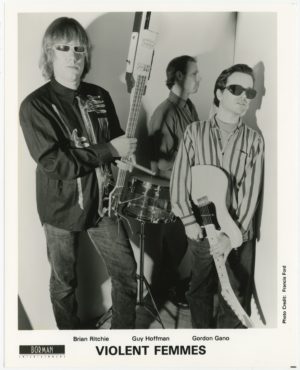

Well I agree with you that it’s unusual. There have been times where I’ve said we’re one of the world’s most popular unknown bands. I know from having discussions with [bassist Brian Ritchie] that we have a similar view in that we would have thought because the people we knew and liked were punk musicians like Richard Hell and Voidoids, Television, Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers, that had a certain level of success, we were striving for that. So we could play the little punk club in London or LA and have some records and that’s doing what we want to do. Or [on the other end of the spectrum] there’s The Beatles and The Stones and Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd.

“There have been times where I’ve said we’re one of the world’s most popular unknown bands.”

Now we have 40 years, basically, of being in some place between those extremes of very small but intense and loyal popularity or enormous and giant. So that’s interesting to me. It’s also interesting to me that when we started, anyone in the industry would tell us that we’re not good and wanted us to go away because it was different and it didn’t fit with anything. I believe that people probably sincerely didn’t like it and were sure that this would never be successful. I think there’s an aspect of the industry that would still be happier if we just went away, and I think there’s a quality of that that’s gone through our entire career.

That also maybe had an advantage in the sense that we’re never out of fashion or dated in a certain way because we were never the most popular thing of the time. Depending on people’s age I’ve heard them say, “You’re the ultimate ’80 band,” or, “You’re the ultimate ’90s band.” Well, it depends how old they are and when they got into our music. We were never on the cover of all the most popular magazines… I don’t know if we were ever on the cover of any magazine! [Laughs.] I’m sure there must be one. We don’t have hits; it’s not like, “here’s our song that’s #1 on the charts.” Our career hasn’t been like that—and I think that’s been a good thing in many ways. FL