The last time I saw Gaspard Augé, he was behind the turntables in the basement of a hundred-year-old factory-turned-venue on the Brooklyn-Queens border, packed wall-to-wall with the coolest people in New York City who’d all been invited out to Frank Ocean’s soon-to-be-notorious retro club-culture tribute party PrEP+. He was spinning a peak-hour set alongside Xavier de Rosnay, his partner in the era-defining electronic duo Justice, and it was everything you’d want a Justice gig to be: dark, loud, sexy, and delicately balanced on the brink of chaos without quite tipping over. It was, he and I agree, the last good party before the world shut down.

Today, Augé, shaggy behind sunglasses and dressed in a retro military button-up with shoulder epaulets, is parked in front of a laptop in his apartment in the 18th arrondissement, which houses a large, keenly curated collection of cool-but-kitschy cultural artifacts from the ’70s: French sci-fi zines and cheesy Eurodisco vinyl, not to mention cheesy, sci-fi-themed Eurodisco vinyl. He’s promoting an album that was already in the works when I last saw him, but feels far more suited to life on the other side of the pandemic.

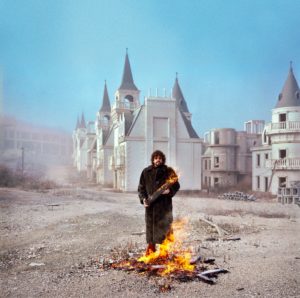

Escapades is his first major musical venture without de Rosnay, and a world away from the black-leather electro-headbangers the pair built their name on. As the title suggests, the album is pure escapism, wafting with exoticism and rococo classic gestures, piled high with ostentatious melodies and high-gloss disco drums, and overstuffed with references to the ambitious art-pop of vintage movie soundtracks and U.K. library music. Leaving behind much of Justice’s taut, nocturnal energy, its scale is panoramic and its mood euphoric—a work of art swept away by its own sense of possibility. It’s unabashedly too-much, which, after this strange year of scarcity and loss, feels absolutely necessary.

“Everyone’s life has been a bit restricted,” Augé says. As he sees it, things were already this way before COVID. Pop culture no longer aspires to match the haute grandeur of classical European art. Pop music has lost its symphonic ambitions, and with them, a lot of their ability to move a listener. “I guess somehow we lost a bit of that vocabulary, you know, like that emotional vocabulary shrank with the music.”

“Something I really like about Fellini’s movies is that you can feel this direct stream of subconsciousness, you know, like there is something very linked to dreams.”

Escapades is Augé’s attempt at correcting this deficiency. From its cover art—a tribute to the serene surrealism of legendary ’70s-era album designers Hipgnosis—on down, it’s an album from another time. Using Justice’s Grammy-winning (for their quasi-“live” album Woman Worldwide) but underappreciated recent prog phase as its launchpad, its 12 instrumental compositions are a cosmic tour of a bygone era of excess and experimentation that once manifested across genres in the post-acid-rock ’70s, from prog rock to krautrock, Eurodisco to psychedelic jazz.

“Force Majeure” conjures up the starry-eyed synthesizer bombast of prog-pop icons Yes, redolent of airbrushed party vans. “Europa” replicates the ominous chamber-music vibe of an Italian psychological horror soundtrack, while also channeling the eccentric experimentation of library music, the commercially produced stock recordings that in the ’70s acted as laboratories for British composers like Brian Bennett and Alan Hawkshaw to experiment with everything from musique concrete to funk. The album is as much a product of curation as creation. And like Augé’s retro design collection, it exists in the blurry space where “good” and “bad” taste overlap, with his expert taste maintaining the proper balance. “Belladone,” the most overtly Justice-sounding track on the album—and one of the few that wouldn’t feel out of place filed under dance music—sounds like it was made for a Xanadu-meets-Emmanuelle sci-fi roller disco Europorn movie that never was.

It’s also a tribute to a different approach to making music than today’s pop. It recalls a time during the music boom of the ’70s where labels were willing to not only indulge ambition and virtuosity, but reward it with massive recording budgets, using mega-selling singer-songwriters and arena rockers to subsidize more avant-garde explorations. It was a brief utopian moment where daring creativity was fetishized, and maximalism—manifested through sprawling concept albums, gatefold LP sleeves, and 11-minute-long Moog solos—reigned supreme. A moment where classically trained keyboardists with cocaine-inflamed egos and Kubrick-sized imaginations could conceivably stake a claim on the record-buying public’s attention.

Escapades has a widescreen cinematic vision that would have fit right in. Augé is a cinema fiend on top of being a (very chic) record geek, especially when it comes to the auteur directors of the ’60s and ’70s, who were able to build idiosyncratic and highly personal visions on an epic scale. “Something I really like about Fellini’s movies,” he says, “is that you can feel this direct stream of subconsciousness, you know, like there is something very linked to dreams.”

“What I like about the ’70s is that there was something very naive and genuine about it. There was something very utopian in a way, with all this fascination with space, and this kind of vogue for possible utopias on another planet or whatever. There’s almost like a childlike innocence.”

Much of Escapades was, in fact, literally dreamt up. “When I was thinking about melodies,” Augé recounts, “you know, you wake up in some kind of half-asleep state and you have this whole orchestra in your head, and then you try to record something the next morning and it doesn’t make any sense. But some of it still makes sense. So I kept those parts and worked on them.” Collaborating with composer Victor le Masne and engineer Michael Declerck, Augé holed up in a pair of Parisian studios for two months to build his sketches out into full compositions, using an array of vintage and modern instruments, live takes that give the album a welcome human touch, and the easygoing energy of an artist with nothing to prove to anyone, creating for creativity’s sake.

“I guess what I like about [the ’70s] is that there was something very naive and genuine [about it],” he continues. “You know, there was something very utopian in a way, like with all this fascination with space, and this kind of vogue for possible utopias on another planet or whatever. There’s almost like a childlike innocence.” Times—and the music business—have changed since then. “There’s really no room left for instrumental music on the radio,” Augé explains. “There’s some kind of, like, dictatorship of the pop song, you know?”

Music really has become a lot more tyrannical since the golden age Augé’s trying to resurrect. Shrinking royalties and a new generation of exploitative practices by the labels have made life even more financially precarious than before for artists below the superstar level. Audiences with shrinking attention spans and growing TikTok habits demand a steady supply of instantly accessible hooks to feed a nonstop content machine where songs are consumed as a never-ending torrent of seconds-long snippets.

For artists within the wide realm of pop music, being a professional musician these days looks a lot like life in any of the other, less glamorous parts of the gig economy: highly demanding, highly precarious, and brutally uncaring. Keeping your head above water means cranking out a constant stream of work at a rapid pace, sacrificing creativity for efficiency as they desperately try to activate pleasure centers that have already been burnt out on a diet of constant novelty. That’s one of the reasons why minimalism has dominated pop for the past decade: it’s fast and easy, a copy-paste aesthetic perfectly suited to austerity and mass-production.

“Especially today when you have so much visual stimulation, it’s important to have these moments where you can just get really deep or even daydream. Moments like this are getting more and more rare.”

For ears that have become overly used to pop music’s post-trap minimalism, Escapades’ maximalism is such a welcome change that it’s almost a relief, like standing in front of a massive oil painting in a museum after spending all day staring at Instagram. Compared to the lean, two-chords-and-no-changes songwriting that’s come to rule the day, a track like “Hey!”—with its swelling melody, flamboyant orchestral-synth-disco arrangement, and sheer panoramic scale—is deliciously, irresistibly complex. It’s bigness. It’s delirious joy. It’s an aesthetic experience that asks nothing of you more than simply letting yourself get lost in it, which in our current moment can feel like an unimaginable luxury. This, more than anything, is what Augé hopes his work can offer.

“Especially today when you have so much, like, visual stimulation,” he says, it’s important “to have these moments where you can just get really deep or even daydream. Moments like this are getting more and more rare. When you can’t really travel, it’s a way of being able to travel a bit in your own head, you know?” FL