The Biosah family has been through a lot. The trouble started in the early aughts, when Emekwanem Ibemakanam Ogugua Biosah Sr. went to jail for a credit card scam. Watching the police raid his childhood home and take his father away in handcuffs shattered Emekwanem Jr.’s world. The Biosahs, who’d been living a middle-class life in the Houston suburbs since the mid ’90s, were dragged back into poverty and forced to relocate to the inner city, where they moved in with Emekwanem Jr.’s grandmother. It was during these early adolescent years that he became Maxo Kream—following in the footsteps of his older brother Ju, he joined the 52 Hoover Gangster Crips and started selling drugs, causing his grandma to kick him out of the house at age 15.

Maxo rapped a little in high school but didn’t start to take music seriously until after he graduated. His 2011 cover of Kendrick Lamar’s “Rigamortis” went viral and his career gathered steam slowly over the next few years, his clout growing with the versatility of his deep-south drawl as he dropped mixtape after mixtape. He was still a Crip, but Kream Clicc—a close-knit entourage of family and friends—was now his core crew. In 2016, he was arrested and charged with conspiracy to launder money. He beat the case and self-released his first studio album, Punken, in 2018, repurposing his prodigious storytelling talent—previously reserved for street scenes and crime chronicles—to detail complex family dramas. Punken’s tracks illustrated the cost of poverty and the horrors of Hurricane Harvey—themes Maxo built on with Brandon Banks, which he put out just two months after signing with RCA in July 2019.

The deal didn’t end the Biosah family’s hardships. Maxo’s younger brother, Money Madu, was shot and killed on March 12, 2020, leaving behind a newborn daughter. Maxo had just returned from a European tour as COVID-19 was beginning to shut down the nation, and there was no way of knowing how soon he’d be able to go out and earn for his family again. But lockdown gave him time to focus on his next project, Weight of the World, which arrives today.

When we spoke with Maxo in September, he was anxiously awaiting a different drop: the birth of his first child, Mackenzie Adaeze Rae Biosah. We talked about family dynamics, crooked prosecutors, walking on water, and Björk (sort of).

A lot of rappers talk about “family over everything,” but you actually put us there in the room with your family and show us what’s going on. Why do you think it’s important to paint them so vividly?

A lot of people who hop up here and tell these stories, they be cappin’ as hell. I’ve really got my family, you can ask them. They tell me, “Don’t show everything!” The shit gets deeper, but everything I say is real. Ask my mama, ask my uncle, ask my granny.

“I’ve been focusing all the attention toward the kids so they can grow up different from how we did, see different shit. They ain’t gonna see no Uncle Maxo smoking rocks or anything like that.”

I’ve heard you say in other interviews that your mom got mad when she heard you putting her business out there in your songs, but that she eventually came around. How do your other relatives feel?

Some support, some be mad, I don’t give a fuck. I make my money off my life. My dad was mad about Brandon Banks—he’s on the cover. The truth hurts, but the truth also sells—you’ve gotta kick that money back to your folks. I’ve really just been working on getting myself right for my family. That’d be selfish, not getting right for my daughter, and I’ve got my niece too. I’ve been focusing all the attention toward the kids so they can grow up different from how we did, see different shit. They ain’t gonna see no Uncle Maxo smoking rocks or anything like that. Maybe a bong, maybe a Backwood [laughs].

As with your family life, you’re very explicit about past illegal activities in your music. It’s become standard practice for prosecutors to use rappers’ lyrics against them. Did that happen to you when you were arrested in 2016?

Hell yeah, man. They hit me up about a video I shot like three months before, like, “Yo, what’s up? You’re saying you sold the most pounds in Houston,” trying to work it into my RICO case. They’re really on my dick like that. HPD, state police, the FBI—they’re the biggest fans, bro. They’re gonna jam you up, try to analyze everything you say. They’re gonna take the picture you paint and try to turn it into a Picasso.

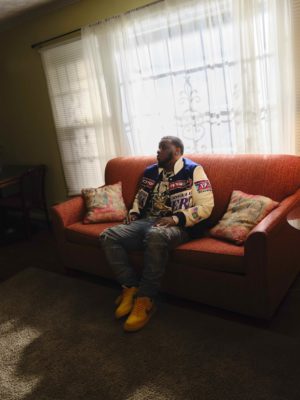

photo by Gem Hale

Do you think the level of authenticity in your music has made you more vulnerable to that?

Not really. I know what to talk about and what not to talk about. Fuck the prosecution, this is freedom of speech. I can say what the fuck I want. Shit, I make money off the English language. What the fuck they want from me? I’m signed to a major label, I’m a taxpaying citizen, they can suck my dick.

“HPD, state police, the FBI—they’re the biggest fans, bro. They’re gonna jam you up, try to analyze everything you say. They’re gonna take the picture you paint and try to turn it into a Picasso.”

“Cripstian,” the first track on Weight of the World, picks up where Brandon Banks left off, calling back to the “carried by six before I’m judged by 12” line from “Meet Again.” Do you see your albums as chapters in a longer book?

Yeah, I can come back and do Brandon Banks II any time. But the older I get and the more in-depth I get with the music, I get more emotional and I open up more to my fans. There’s a lot of shockers on this tape if you pay attention. It took time to really build the cohesiveness of it, but fuck, I had the time. I had nothing going on with this pandemic. It’s not like Maxo ducked out—I was going to the grocery store with everyone else.

What do you think religion and gang life have in common?

Same shit. If you’re a gang member, you’re idolizing something, whether it’s the flag or the man. It’s the same goals, same practices, sacrifices, discipline. For some people, being a Crip is like being a hoodlum, a gangbanger. For other people, it’s a badge of honor, like being in the Navy.

The first half of “They Say” is sort of a self-dis track. What was it like to direct all that hate at yourself?

A lot of those criticisms were exaggerated. Nobody’s gonna play with my crippin’. I don’t know what they talk about behind my back, but I was just having fun with it. I was supposed to do that track with J. Cole, so when that beat came on and I was like “They say Maxo a bitch!,” everyone in the studio was like, “Yo, this is supposed to be a Cole track”—but it was hard, so we kept it. And then my producer teej—I don’t know what he has against me, but he loves to hear me talk shit about myself—was like, “This is dope, keep going!” It’s kind of a cap, don’t nobody play with me in these streets. I didn’t even wanna put that song on the tape because of that. I didn’t want nobody getting scared, like, “One day you play with Maxo, next day you’ll be a new weed strain” [laughs].

“It took time to really build the cohesiveness of it, but fuck, I had the time. I had nothing going on with this pandemic. It’s not like Maxo ducked out—I was going to the grocery store with everyone else.”

“Big Persona” is sort of the opposite of that song. It’s the biggest flex on the album, with the Tyler, the Creator feature and the lyrics that feel like throwbacks to your mixtape years. How has your persona changed over time?

First off, R.I.P. Fredo Santana. That’s where we got it from. My brother and I, we took that and put it on our backs like, “Fuck it, we Kream Clicc.” We’re getting older, so we’ve already settled into our persona, but now it’s the nice shit: owning property, the fancy cars, the jewelry, the lavish lifestyle. That’s what persona means to me: big time living for me and my folks.

Both “Worthless” and “Greener Knots” have really dreamy, lo-fi beats. It made me wonder what kind of music you like to listen to outside hip-hop.

I’ve got a wild span of music that I fuck with. I listen to hip-hop and drill—and I mean, to me, Durk and Future are R&B, but fuck, they call that shit rap so I guess I just jam rap [laughs]. I’m cool with EDM, though.

I’ve always wanted to ask you about the production on “Mob of Gods” from one of your first tapes, Quicc Strikes. It’s got a sample from “Jóga” by Björk that blew my mind when I first heard it. Are you a Björk fan?

Nah, man. I was doing the song with A$AP Ant, so I was like, “Bro, get a crazy video game sample on some evil shit.” That’s how I was comin’. I don’t know nothing about no York [laughs].

“Mama’s Purse,” to me, is the album’s climax. There’s that line, “You see them crackheads and them junkies / That’s my uncles and my aunties,” and later, “You see a pimp and prostitute / Well me, I see a happy couple.” Are those lyrics meant to be food for thought for your fans who don’t know what it’s like to grow up the way you did?

I was just looking at it like, “Shit, that’s how the hood looks at it.” I’m not really saying the crackheads on the streets are my aunties and uncles. But where you might think “Oh, that’s a crackhead,” I’m like, “You good, Unk? Need a dollar?” Some people look at a pimp and a prostitute and see social destruction, but from a real hood perspective, they just gettin’ money. A lot of rappers don’t think about that kind of thing because they just go to the clubs and back. They ain’t thinking about Pitchfork and festivals and really getting out there like I have. It’s made me think: “I’m really from that shit and I can shed a light on it for people who don’t know that world.” Don’t get me wrong: I’ve got all that shit in my family, but it’s not only my family, you feel me? A lot of us have “crackheads,” “meth heads,” “hookers” in our families, but it’s all just humans, bro. Whether you’re upper class, lower class, we all deal with the same bullshit. FL