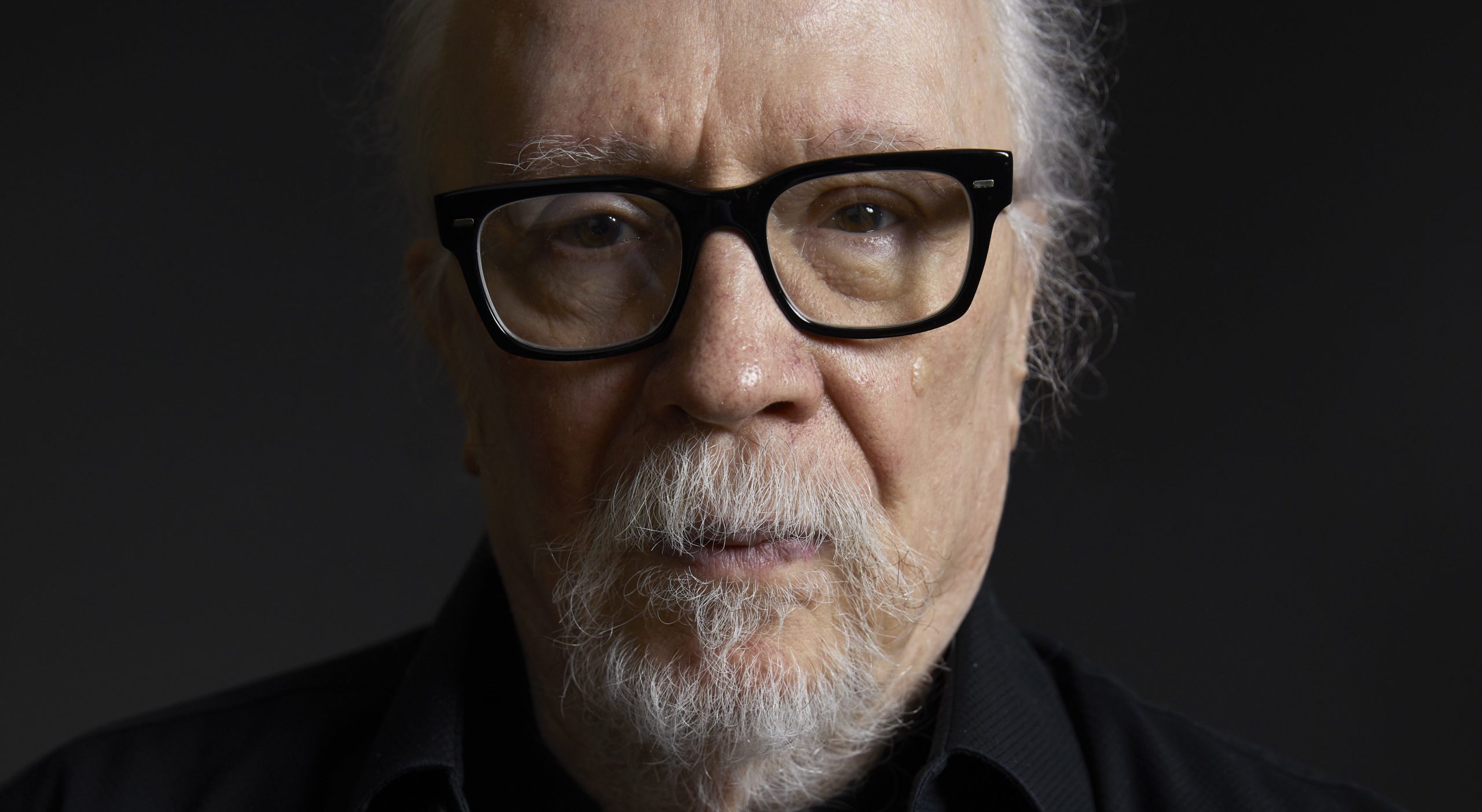

When John Carpenter answers his phone, it’s a late morning where he is, in “beautiful Hollywood, California,” as he puts it, just hours before the 2021-22 NBA season kicks off. Both of his favorite teams, the Golden State Warriors and Milwaukee Bucks, are playing tonight. He’s looking forward to the games rather than back at the recent theatrical and streaming release of Halloween Kills, the long-awaited middle section in David Gordon Green’s trilogy reboot of the series. Carpenter talks blissfully, his voice ringing in with a type of chill softness earned from decades of working relentlessly. The specter of that work still follows him—in film as well as in music.

My earliest film memory involves being way too young—maybe six or seven years old—and watching some cut-up, censored syndication of Halloween on late-night cable with my father. The film came out when he was a teenager, and has since become steadfast in my yearly October viewing rituals. This is a kinship I share with so many other fans of horror: owing so much of my taste to Carpenter’s artistry, to the mythology of on-screen killing he instituted—and I tell him so, to which I’m met with a gentle “thank you.” Those two words are more than enough to quench the dreams of my younger self, who most certainly was petrified of the imaginary, cinematic beats I conjured in the dark, empty hallway of my boyhood home, of Michael Myers—or “The Shape,” as he was originally called—and of the hollow, electronic score that swells and explodes throughout the 1978 film. It’s a simple tune—built from the skeleton of a piano in 5/4 time, which Carpenter learned to play after his father taught him a similar melody on a set of bongo drums—that has withstood numerous periods of aesthetic reconfigurations in the horror genre.

And Halloween has withstood, too. Now in its twelfth installment (or eleventh, if you don’t count the Michael Myers–less Halloween III: Season of the Witch), the franchise has lived through the craze of ’80s slasher flicks, the craze of self-aware mid-’90s killings, and the excessive gore of the early-’00s. In each film, Carpenter’s signature theme gets new legs, whether it’s a backing drum machine or high-pitched, nasally distortion. Despite four decades of nixing and rehashing timelines, screenplays, and bloated director’s cuts, Carpenter’s original score prevails, even when a different composer tweaks it. The Shape’s backing tracks are in the company of films like Jaws and Psycho—untouchable classics with scores that even non-horror fans can diagnose. And Carpenter’s explanation for where his signature sound comes from is short and sweet. “It’s just creativity, I suppose.”

“There’s an ease in getting to that creative space with Cody and Daniel. We get there pretty fast, though, because we all bring different things to the table.”

The Halloween theme is as menacing as it is stark, even in retrospect. Carpenter has said before that if you have an ear for music composition, you know from the jump that it’s a simple song. But even that simplicity endures, traveling unscathed through eras of bombastic horror film theme songs and scores. “Sounds have changed enormously since 1978—and synths especially have changed a great deal,” Carpenter says. But with the help of his son Cody and his godson Daniel Davies, Carpenter and company have revamped the classic tune for the new trilogy, bringing it into the modern age without losing the haunting minimalism that’s made it so famous. “Back then, I was working with synthesizers that you had to tune up every time you used it. It was just really primitive. But now, you can sound like an orchestra. That’s the big secret to all of this,” Carpenter adds, cheekily.

His interest in film music dates all the way back to 1956, to Fred M. Wilcox’s Forbidden Planet, a color sci-fi picture that made Robby the Robot famous in American popular culture. As a kid, classical Hollywood composers like Bernard Herrmann and Dimitri Tiomkin affected him greatly, but it was the influence of the fresh, all-electronic compositions in Forbidden Planet, done by Louis and Bebe Barron, that sent him orbiting. “The [Forbidden Planet] score changed my life,” says Carpenter. “It was stunning. I’d never heard anything like it before.”

Carpenter’s incredible decade of directing—Halloween, The Fog, Escape From New York, The Thing, Christine, Big Trouble in Little China, and They Live—was also an incredible decade of scoring (sans The Thing, which was scored by Ennio Morricone). And while he hasn’t been in the director’s chair since The Ward in 2010, Carpenter doesn’t regret staying away from it—instead preferring the privilege of going into a studio and improvising backing tracks for the screen. “Directing is hard work,” Carpenter adds. “I don’t want to work that hard. I’ve got things to do; I’ve got basketball games to watch. I don’t want to get up in the morning.”

“Directing is hard work. I don’t want to work that hard. I’ve got things to do; I’ve got basketball games to watch. I don’t want to get up in the morning.”

In Halloween Kills, most of Carpenter’s musical work occurs in the present, but there’s a 10-minute flashback to 1978, just minutes after Dr. Loomis shoots Michael six times in the chest (a statistical fact repeated over-and-over again at the beginning of the now-nixed timeline of Halloween II in 1981). Green does a wonderful job recreating the grain and texture of the world Carpenter and Debra Hill created so long ago in an effort to feed the audience exposition of what happened after Halloween in this new timeline. But period precision and plot fluff aside, the scenes feature a sharp return to the original music, revisited by Carpenter and mixed to fit the era. “That was the most important thing,” Carpenter mentions. “Those sounds back then, they were just a lot more primitive. That’s why that sequence feels so much like the original.”

Of course, Halloween Kills lives up to its title. There are gratuitous acts of carnage at every turn, and not even characters that Carpenter created in 1978 are able to survive Haddonfield’s town-wide act of vengeance against Michael Myers. I ask Carpenter what it’s like soundtracking the deaths of beloved characters he created, but whose deaths he didn’t write. “Killing beloved characters? I love it,” he responds, laughing, as if the answer was always obvious. But he’s quick to note that there’s one character he hopes makes it to the end. “As long as Lindsey [Kyle Richards] doesn’t die. She’s my girl.” Carpenter’s never soundtracked a more persistent, gorier flick, and that truth comes out in the ferocity of the sounds he layers over brutal quick cuts of Myers busting the brakes off of anyone who gets in his way. It’s not just synths anymore; it’s drum machines and chamber echoes. Real haunted soundscapes, each ferociously punctured with jagged instruments that thrash and sing evenly at once. “All of this is joyful for me,” Carpenter tells me in one of the most relaxed, content tones you’ll ever hear from someone whose day job is pairing music with murder.

Carpenter’s scores for both movies so far released in this current Halloween trilogy were done alongside Cody and Davies, and keeping the work within the family helps combat the challenge of producing new sounds every session. “It’s a wonderful job. It’s great to have a second career when you get old,” adds Carpenter. “There’s an ease in getting to that creative space [with Cody and Daniel]. We get there pretty fast, though, because we all bring different things to the table.” Carpenter himself brings experience, while Cody and Daniel bring virtuosic keyboard playing and sound mastering, respectively. Most of their work is improv, which entails the three of them crowding around each other and tracking soundscapes over a scene playing on a nearby monitor. “We interchange ideas and feelings, so all of it flows right along.”

Whether or not Michael’s story will finally come to a close with Carpenter’s score pulsating in the background of Halloween Ends remains to be seen. “That information’s too sensitive,” Carpenter chuckles. But when I ask if Michael is actually killable or not, the Master of Horror can only offer up one inch of confident insight: “No. Well, I don’t know. I suppose, in the right hands, he could be. I think Jamie Lee [Curtis] can do him in.” FL