This article appears in FLOOD 12: The Los Angeles Issue. You can purchase the magazine here.

For more on Edward Colver, visit his official site here.

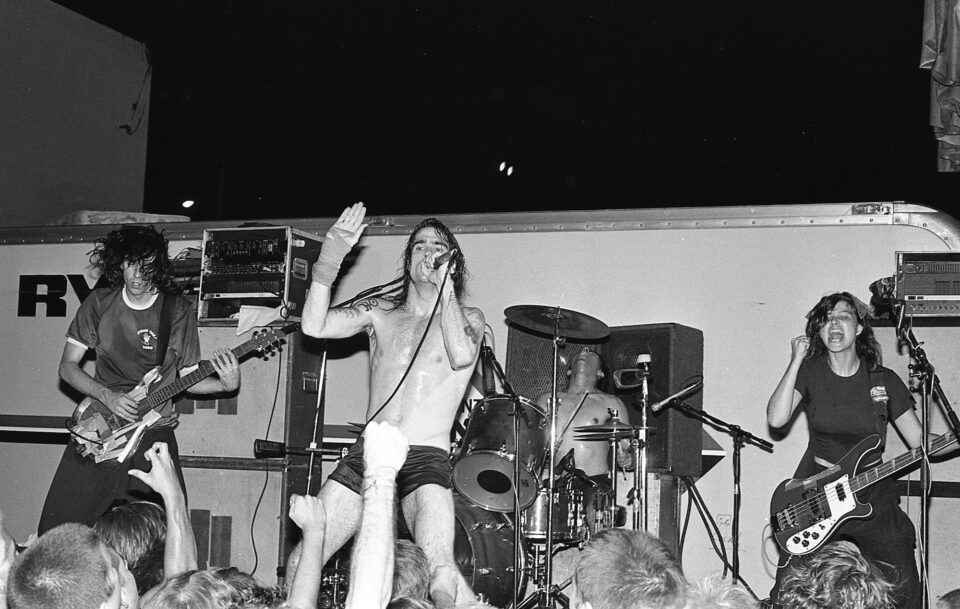

Black Flag, Circle Jerks, X, Germs, Fear. Edward Colver’s name might not be as familiar as these Los Angeles punk legends, but his work is just as crucial in defining the imagery and legacy of punk rock in Southern California and beyond. From 1978 to 1984, the photographer was out at LA-area shows nearly five nights a week, capturing the most dramatic, revealing, and profound photos of the era, which would leave a lasting influence on generations to follow.

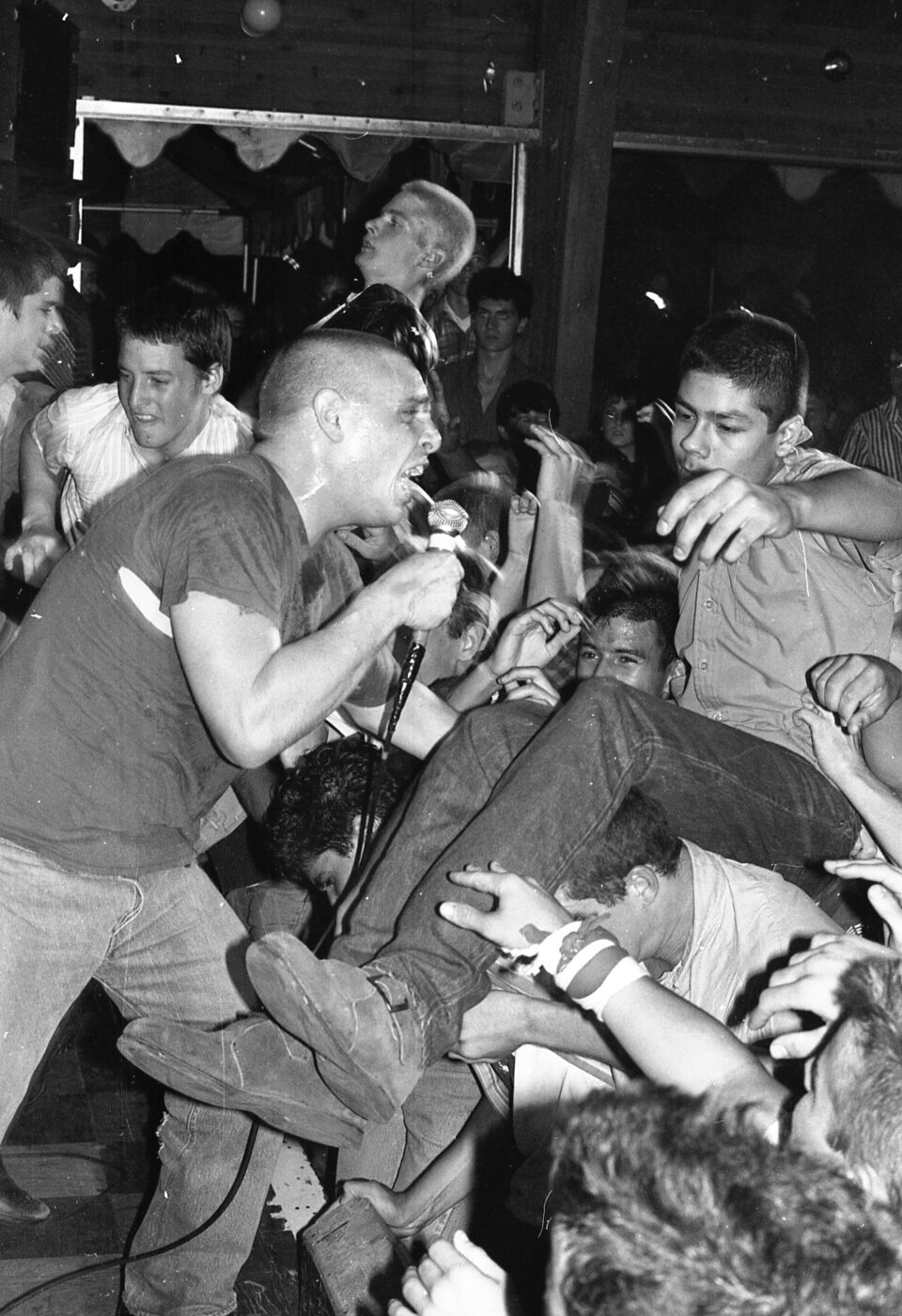

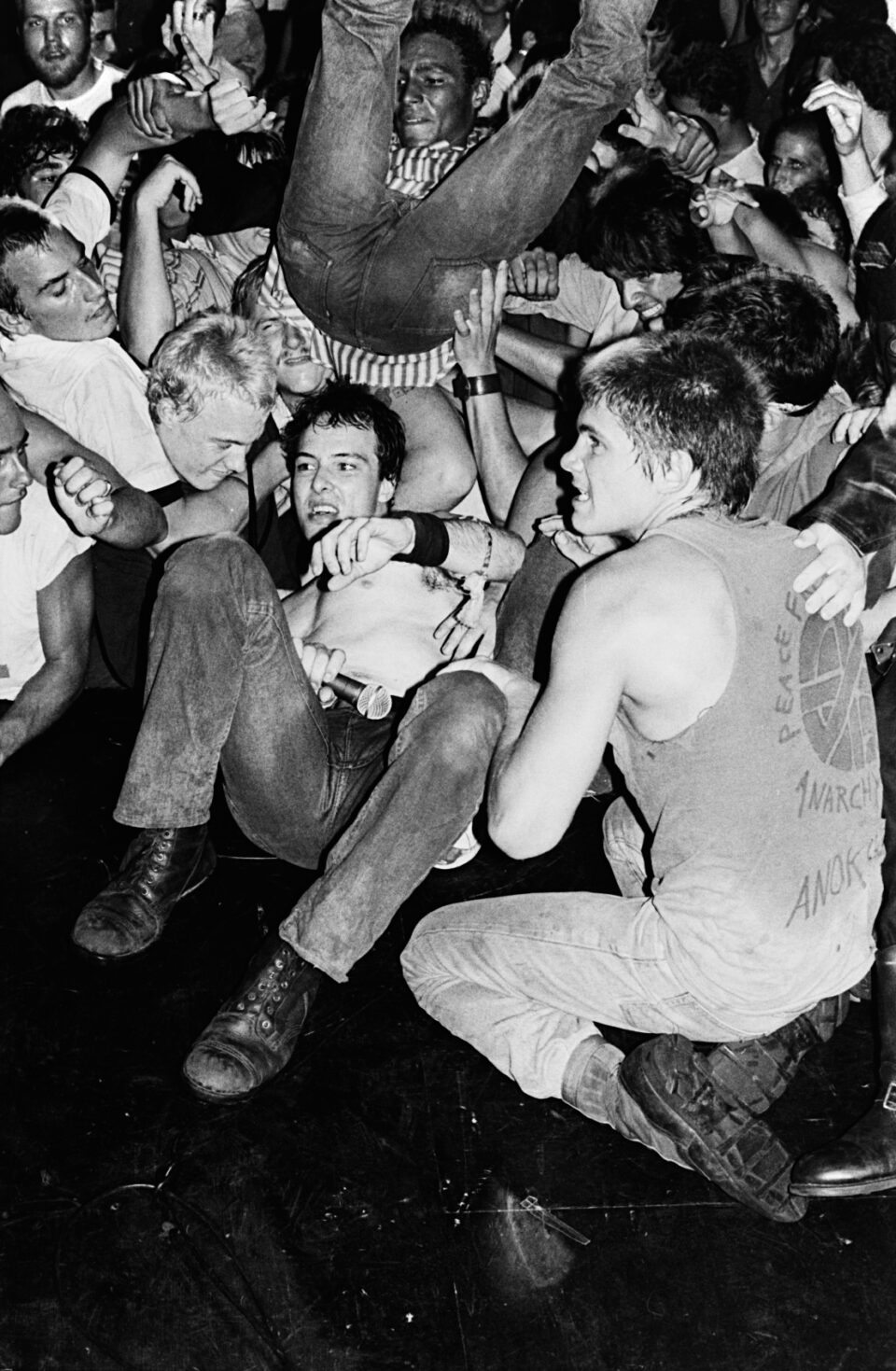

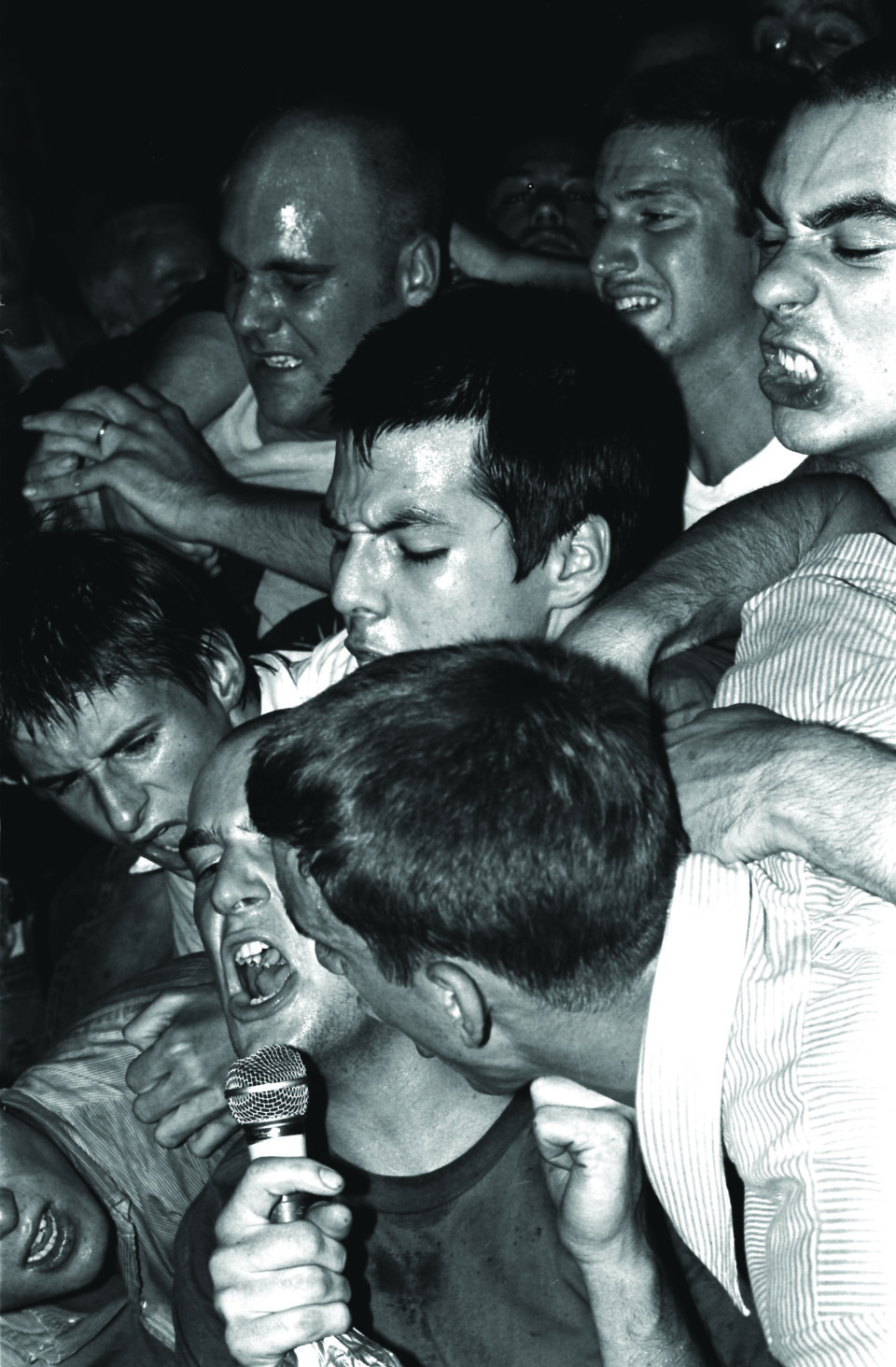

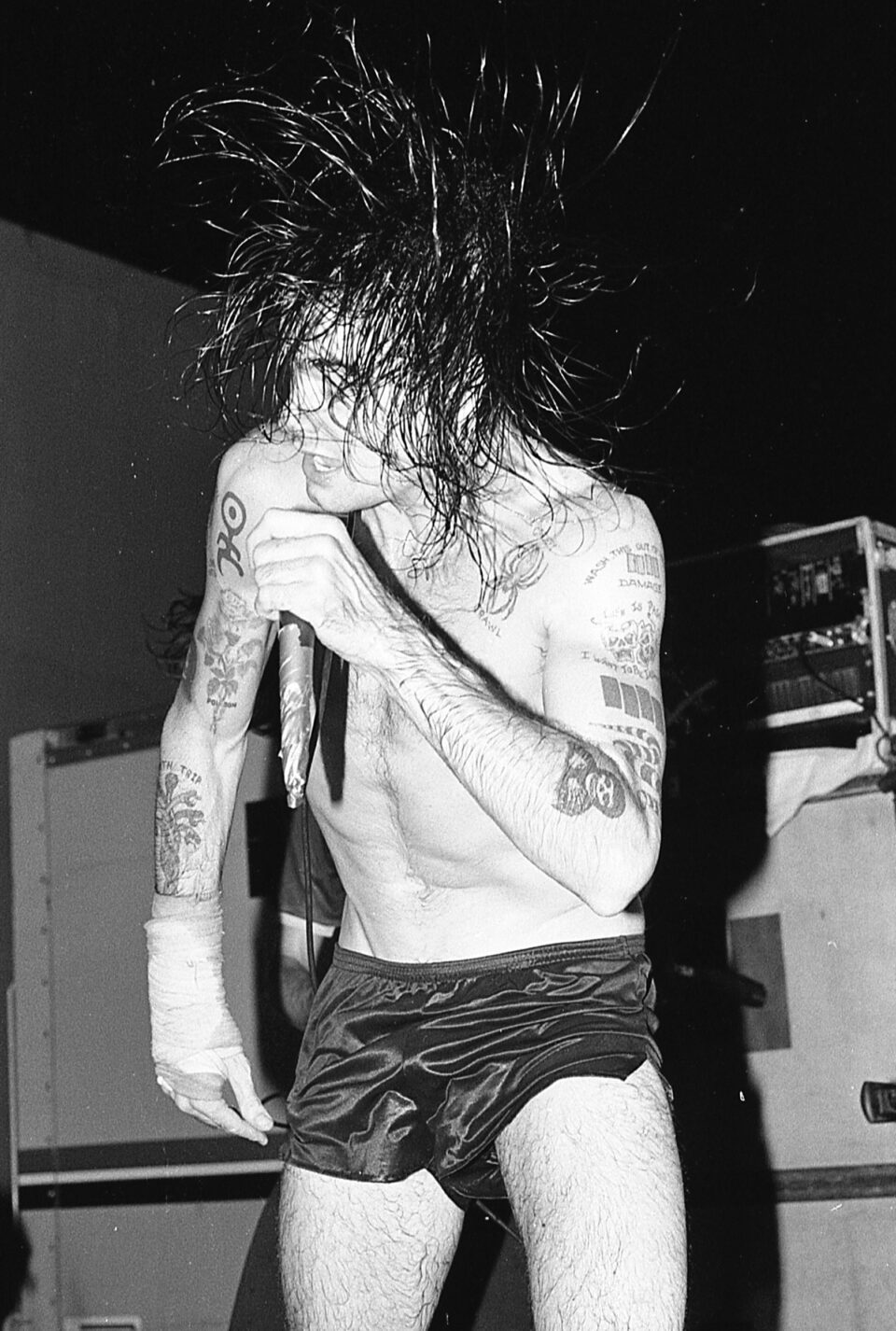

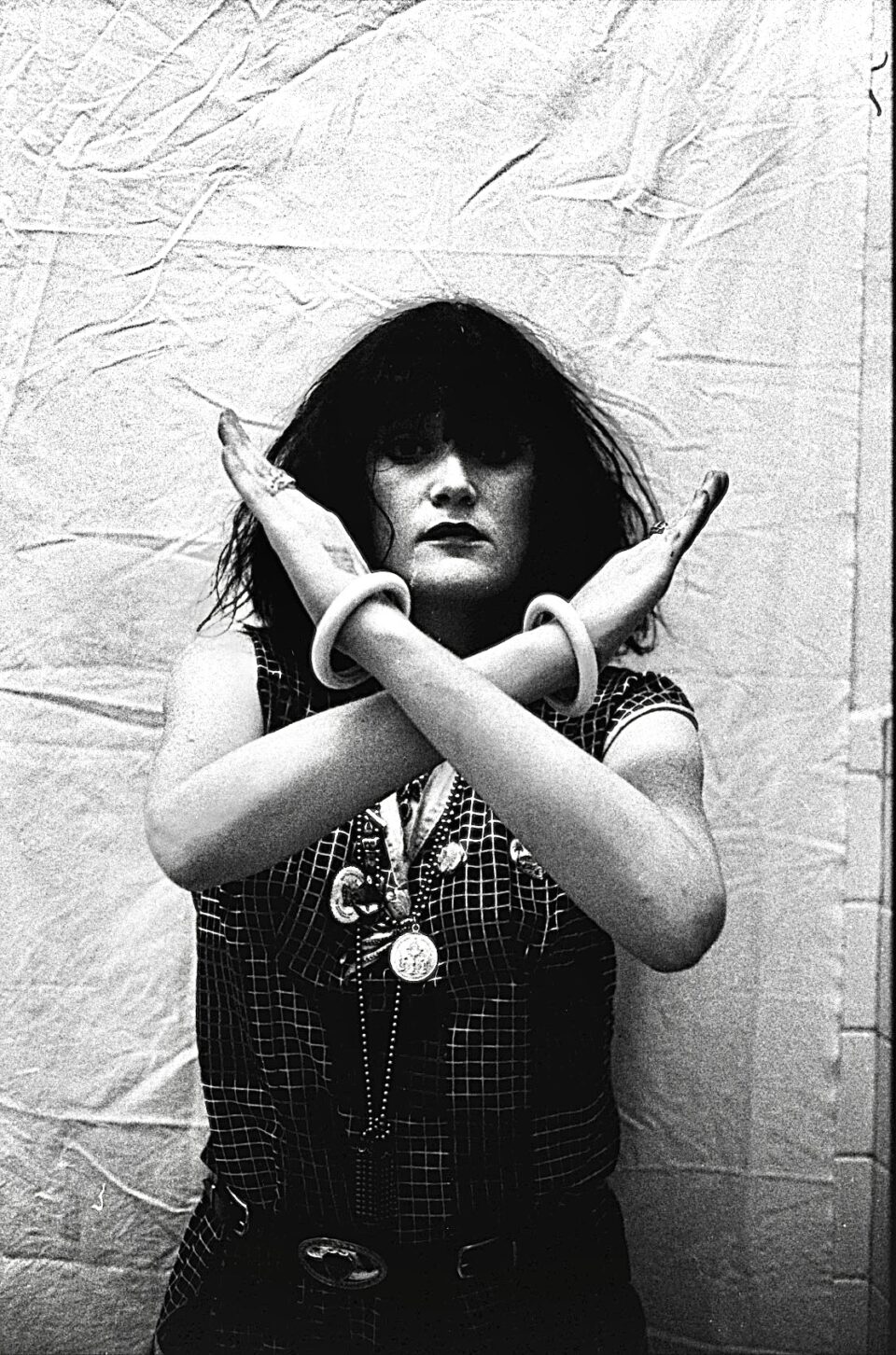

At a time when he was often the only photographer in the room, Colver was not only capturing the scene, he was part of it. He was in the pit, on the stage, or crushed against barriers, with his camera often just inches away from the action. Shot mostly in black and white with a 50mm lens, his photos provided a cinematic view into the period and a blueprint for the look of punk rock to this day.

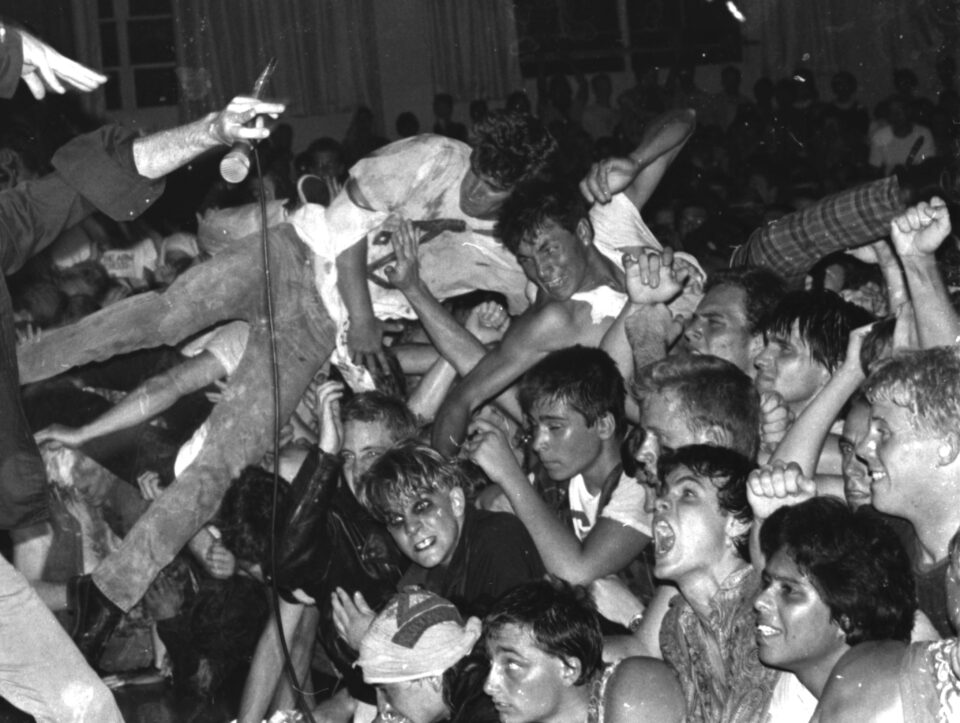

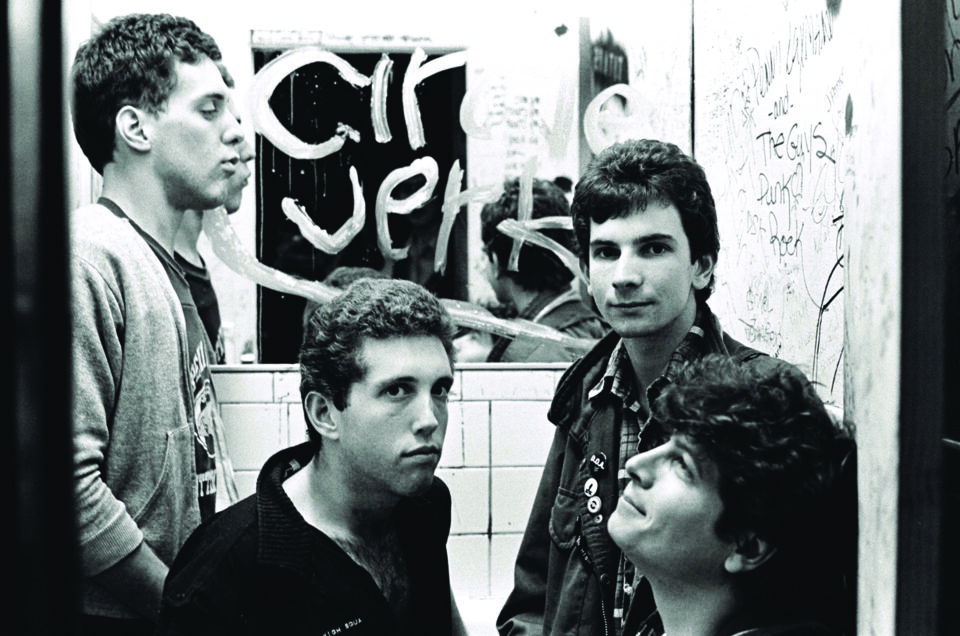

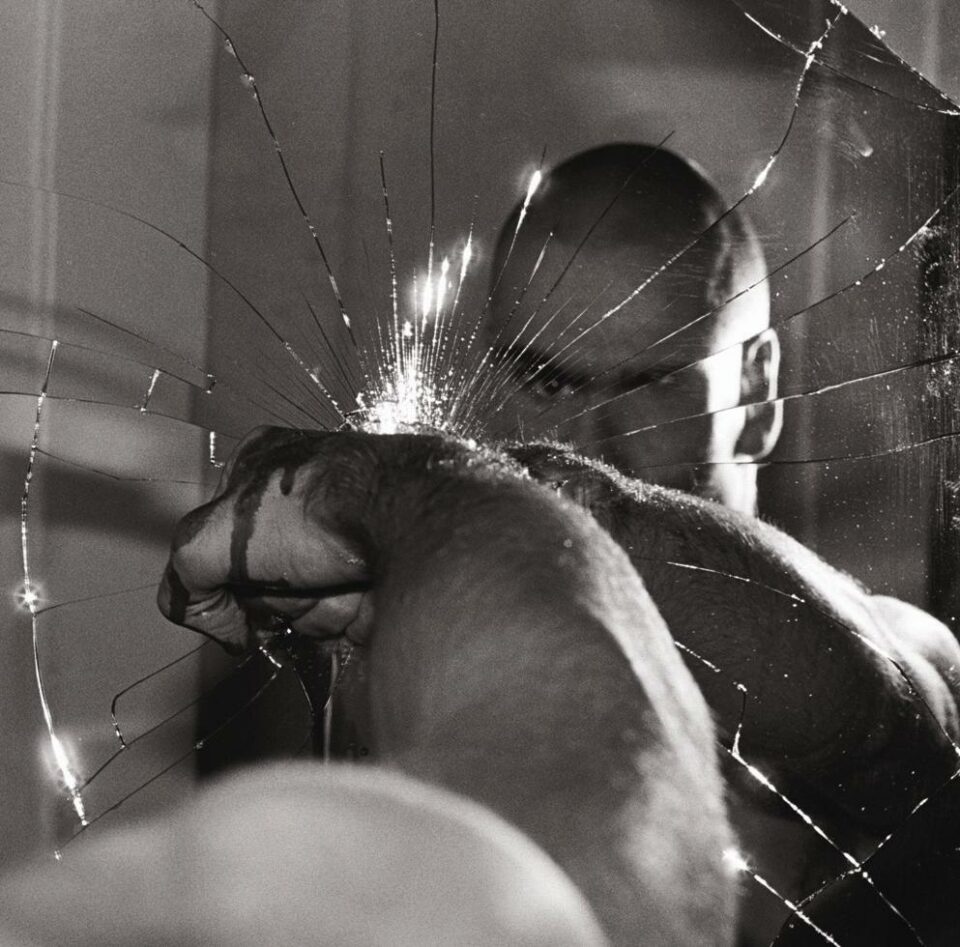

In 1980, Colver photographed his first album cover, the crowd shot that emblazoned Circle Jerks’ seminal debut Group Sex. Covers followed for Black Flag (Damaged), Adolescents (Welcome to Reality), Bad Religion (How Could Hell Be Any Worse?), Red Cross (Born Innocent), and countless others. His photographs have since been featured on over 500 album cover packages.

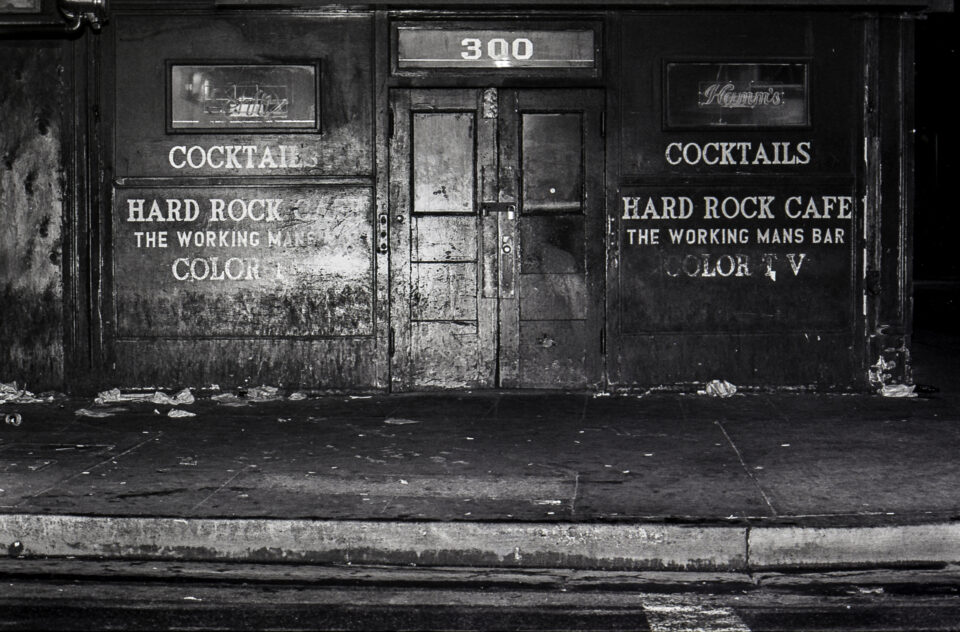

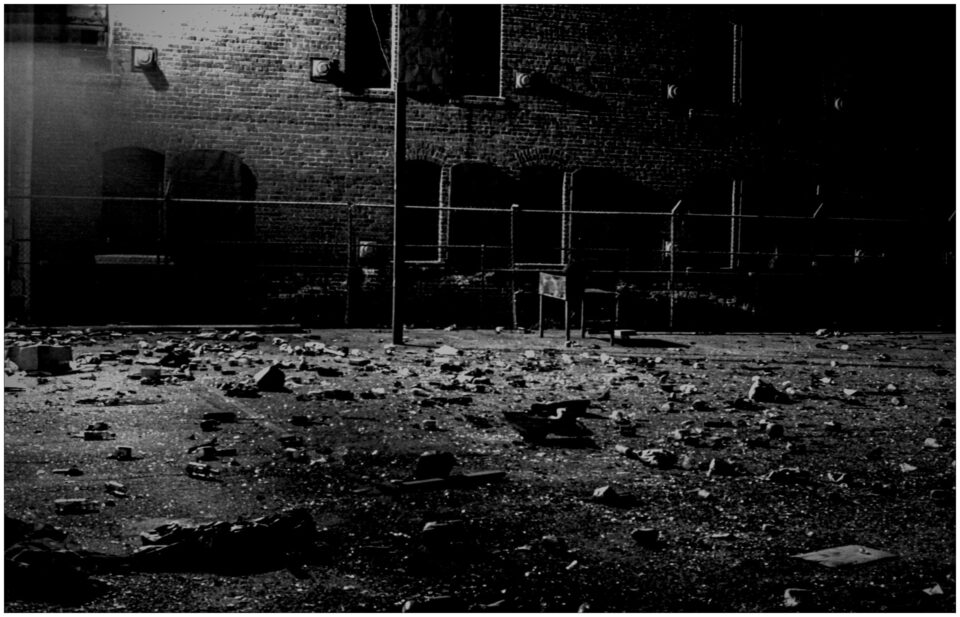

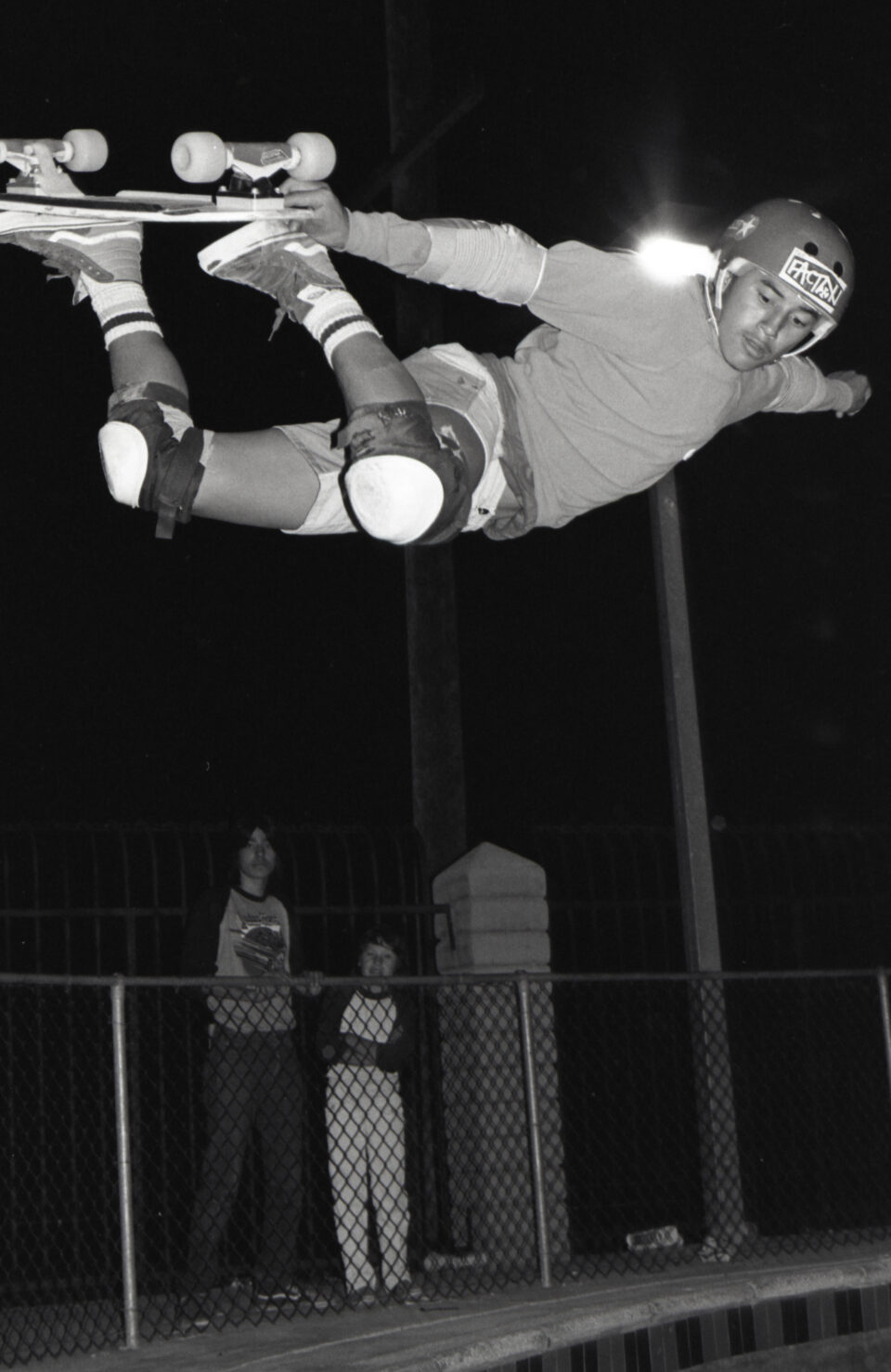

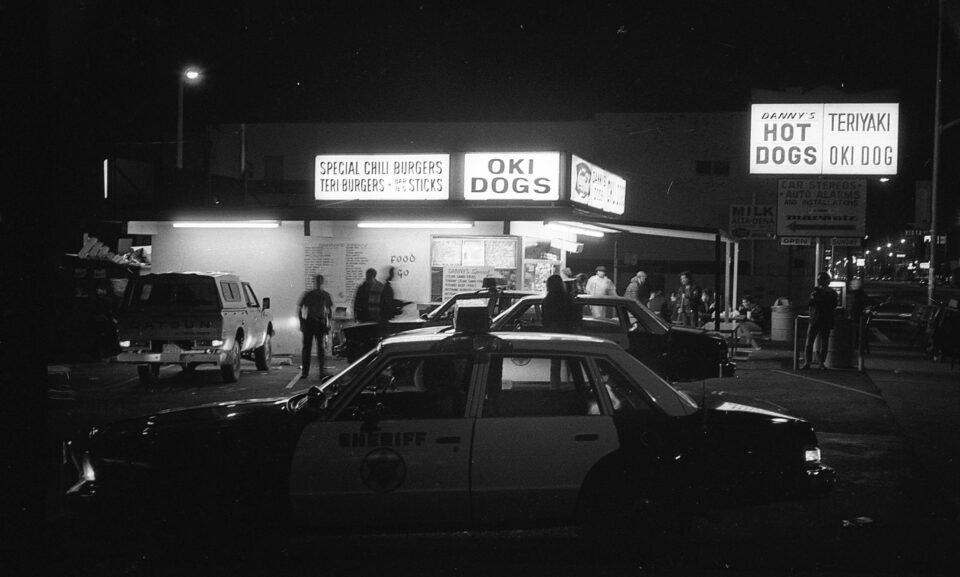

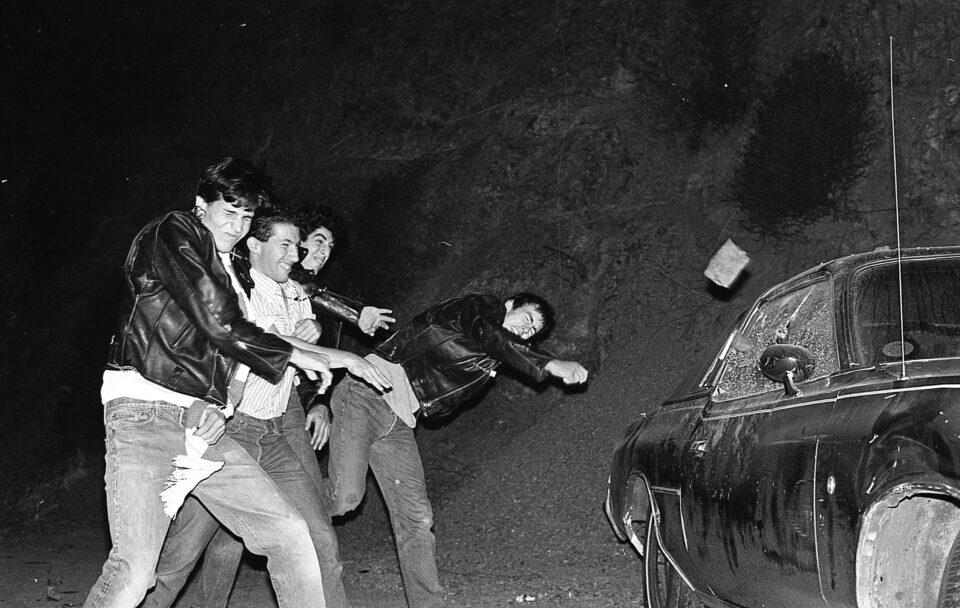

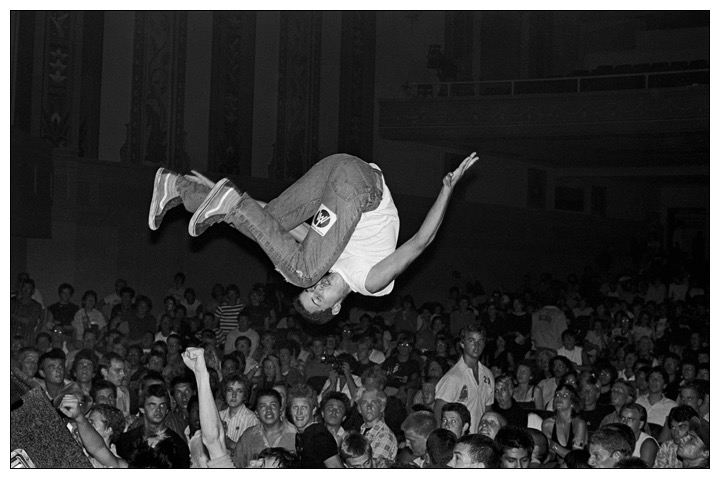

It wasn’t just the bands. It was Colver’s striking images of police activity outside of venues, dimly lit streets in Skid Row shot in the middle of the night after shows, boots adorned with chains and accessories at punk hangout Oki-Dog, weathered gig flyers encrusting old telephone poles, and graffiti splattered on backstage walls. His iconic 1981 “flip shot” of skater Chuck Burke stage diving during the Adolescents’ set at Perkins Palace has become one of the most well-known punk images ever.

Ed Colver, self-portrait

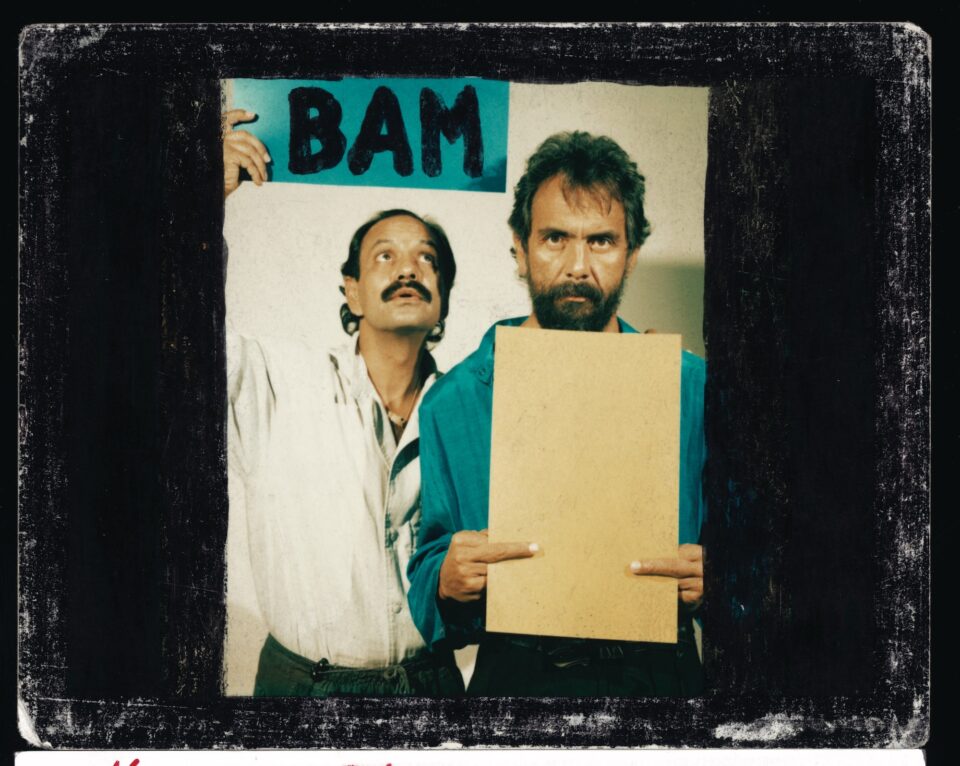

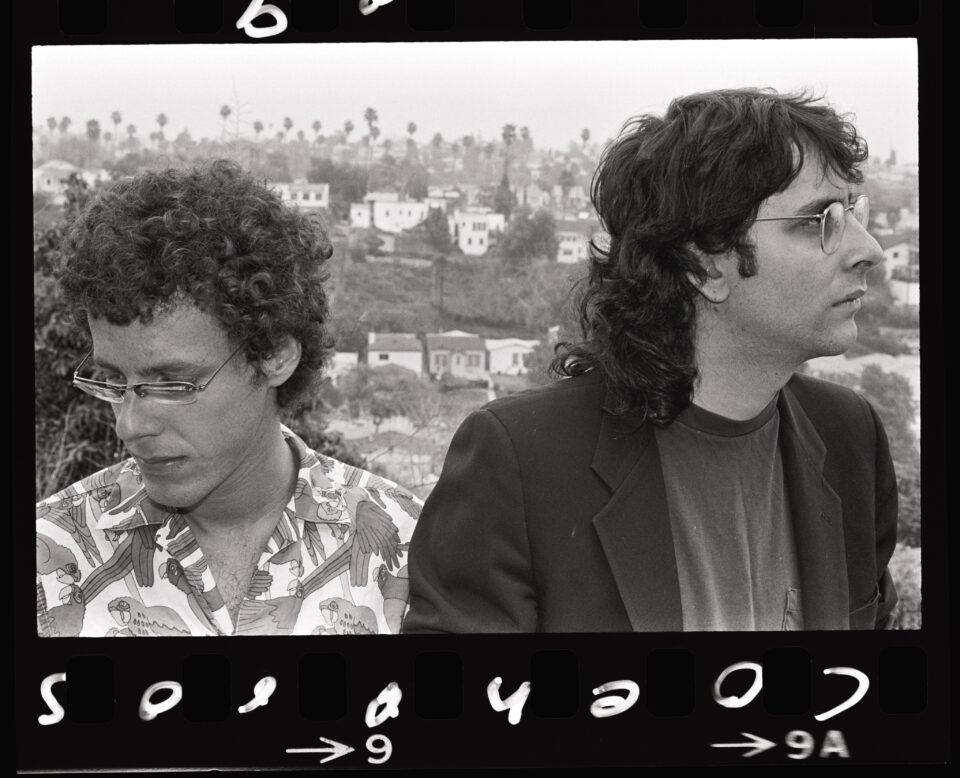

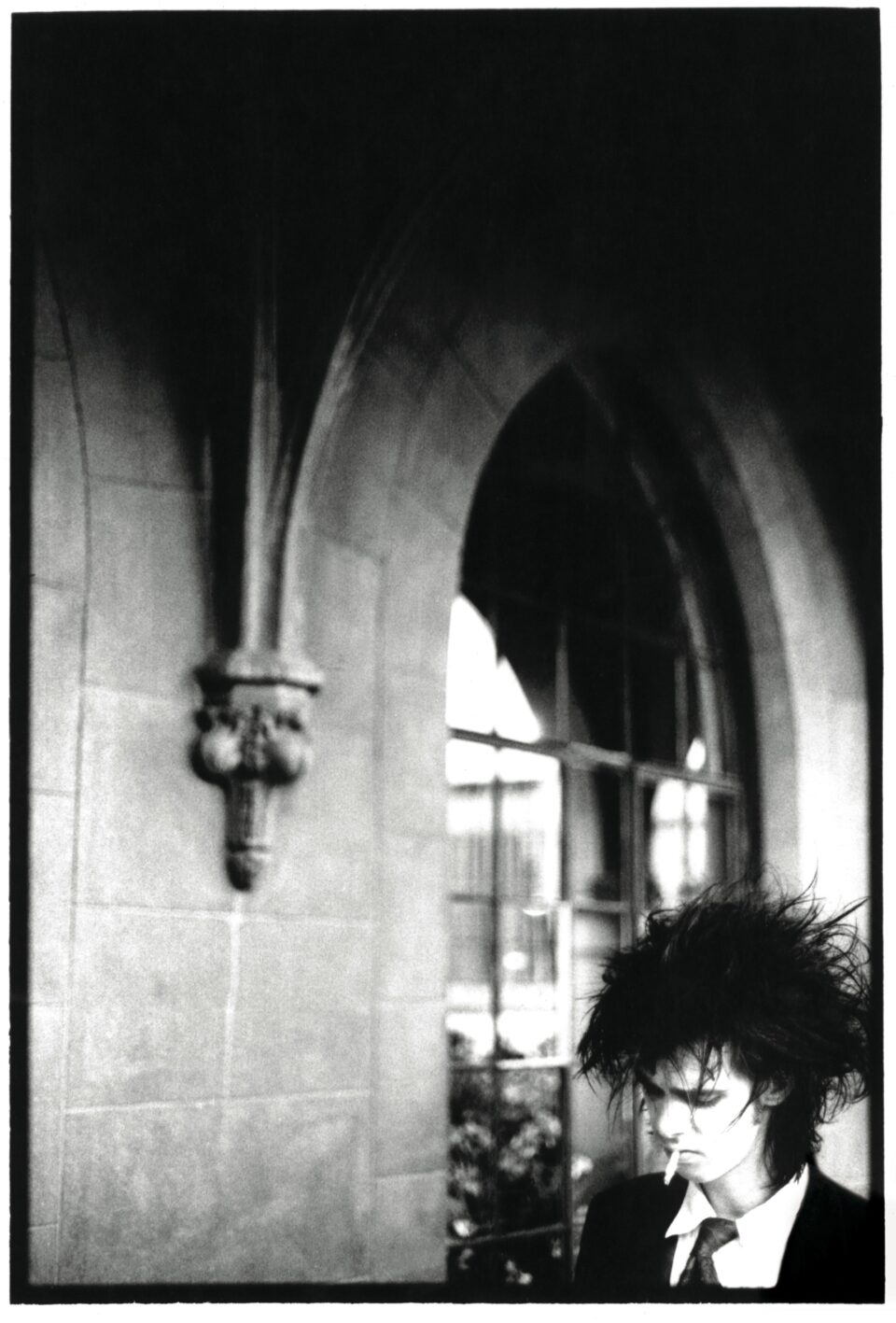

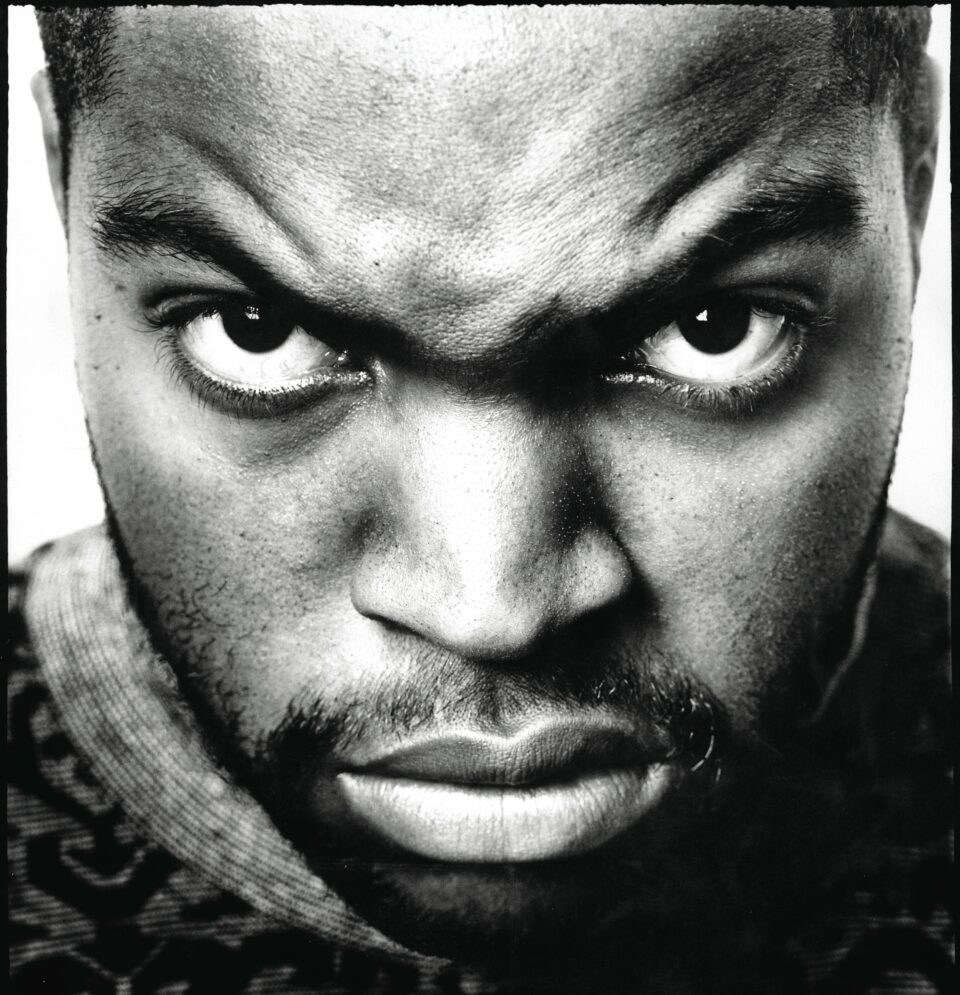

It wasn’t just punk rock. There’s Danny Elfman on the set of Weird Science, Nick Cave on the porch of the Chateau Marmont, the Coen brothers promoting their first film, Wall of Voodoo’s Stan Ridgway in the middle of an abandoned downtown street, Cheech and Chong on the cover of BAM Magazine, Ice Cube’s intense glare on the rapper’s Greatest Hits album, and countless photos of a young R.E.M. on tour in the early 1980s.

When we first started discussing an LA issue, Colver was one of the first people we wanted to include. “What made you think of me?” he asked, after I reached out to feature him. “My photographs have gone around the world without credit. Many people know the photographs but have no idea I shot them.” Hopefully we can have some small part in changing that.

We meet for our interview at Colver’s 1911 Craftsman-style home in Highland Park, where he greets me at the door with four small dogs fluttering about. He welcomes me in and points to stacks of prints, negatives, flyers, ticket stubs, and other punk paraphernalia piled on a table. “I’ve been digging through stuff for my next book,” he says. His first book, Blight at the End of the Funnel, is long out of print, and routinely sells for over $500 on the secondhand market. We head to the back porch to talk, overlooking a backyard filled with gothic sculptures, skeletons, chimes, lanterns, wooden ladders, and a very large 20-year-old sulcata tortoise named Shim. He tells me he’s never used a computer—all of his photos were hand-printed—but his wife Karin got him an iPad, and he has thousands of photos scanned on there. We start the interview, regularly stopping to flip through a never-ending scroll of classic photos, with hundreds of rare or unpublished images of everyone from Dead Kennedys and Red Hot Chili Peppers to relative unknowns like Mau-Maus and Super Heroines.

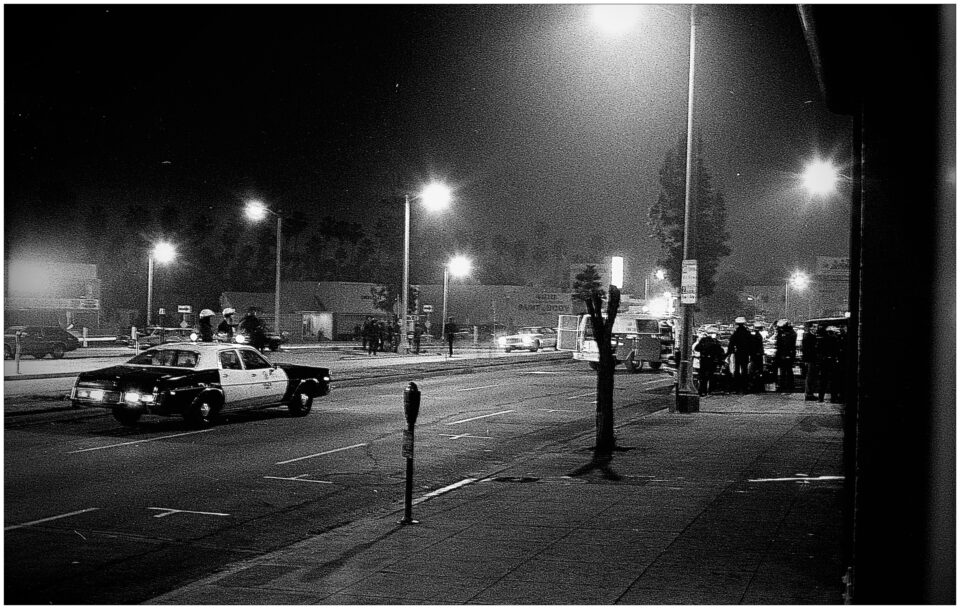

Opening night of The Decline Of Western Civilization on Hollywood Blvd., 1980. Photo by Edward Colver

It can be rare to find someone in LA who’s from here, but you’re actually a third-generation Southern Californian.

Yeah, my great-grandfather and grandfather raised oranges in Covina and my father was a forest ranger in the San Gabriel foothills for 43 years. When he retired they named the tallest peak on the ridge below Mount Baldy after my father: Colver Peak on Sunset Ridge. Bush Sr. gave him the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Award at the White House. Thought that was pretty cool.

Did you grow up in Covina?

We lived in San Dimas Canyon in a ranger station, then Glendora, and then Covina. I lived in Upland and La Verne for a little bit, then back to Covina, and then downtown in ’84. I’ve been down this way ever since.

When you first started photographing shows, you were driving in from Covina.

Yeah, I’d go to Riverside, down to the beach, to Hollywood, to the Valley. I drove and drove and drove all of the time.

What year did you first start venturing out to discover the music scene in LA?

1966, when I was 16.

Oki-Dog, circa 1979-80

Dead Kennedys grafitti car, 1982

Who were you seeing?

Oh, I saw The Seeds. I saw the Mothers [of Invention] when Freak Out came out in ’66. I was a huge Mothers fan. I drew a painting in high school of Frank Zappa, and he saw a Polaroid [of it] many years later through Rhino Records which was kind of funny. I grew up listening to hard psychedelic music and underground stuff. I saw a lot of the San Francisco bands.

So you were going to the Whisky, The Trip, Pandora's Box…

I was standing outside of a club called Bido Lito’s that was on Cherokee. I think The Bees were playing. I could hear them, my brother and his friend and I were hanging outside, and the cops showed up and they were gonna bust me for curfew unless my brother took me home right away. I saw the Cream at the Whisky in ’67. I loved Tim Buckley, saw him four times. I used to see Iron Butterfly at a club called The Galaxy, which was just like a little tiny hole in the wall. I saw Iron Butterfly there at least three times. I fuckin’ loved those guys. Lots of feedback and shit. I love feedback guitar. Saw The Kinks at the Whisky, T. Rex at the Whisky—I’m not a big fan of pop music, but T. Rex rules. Big fan.

Nick Cave, Château Marmont, 1985

I understand you were primarily self-taught as a photographer?

Yeah, I’d say that I’m self-taught. I took a beginning photo night class at UCLA. I learned a few things, and then I took an intermediate class, and I didn’t learn anything from that guy. One thing that was interesting about that instructor was you’re supposed to bring in some of your work. It was 1982 or something...and the guy stopped the class and said [of my photos], “These come from an insider. These people are familiar and know this guy, none of you could take these photos.” I had never even thought about it, just being omnipresent in the punk scene. Just hanging out with my friends and stuff. And this guy kind of called it like that. I was like, “Oh wow, yeah.”

You know, people fuckin’ hated punk rock back then. I thought, “This shit is amazing, it's great what's going on, this is nuts.” But people hated it. I took thousands of photos. If I had any clue it would become the history it did, I would have taken twice as many. Who would have thunk it?

“You know, people fuckin’ hated punk rock back then. I thought, 'This shit is amazing, it's great what's going on, this is nuts.' But people hated it. I took thousands of photos. If I had any clue it would become the history it did, I would have taken twice as many.”

Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, The Barn at Alpine Village, 1982

At what point did you start taking your camera? What inspired you to start taking photos?

In late ’78 I got a hold of a piece-of-junk 35mm camera and started going to shows again. I kinda sat out the ’70s, there wasn’t much of anything I wanted to see. There was The Stooges and Patti Smith, but not much else. I saw a news report about the underground music scene. I thought, “This looks kind of intriguing.” I went out and started going to shows and made this huge, important distinction early on between punk and new wave. No clue why those two terms are used in the same sentence. They’ve got nothing to do with each other. The new wave is just like modern pop. Punk is a whole other thing. I thought it was strange how they lumped them together. Bands like Talking Heads, Blondie, and stuff—excuse me folks, that's not punk rock. You’re out of your fuckin’ mind. LA hardcore was punk rock. I’d also like to say, since there’s all that debate of where [it started]….it’s Iggy [Pop], fuckheads. Iggy started this shit. It didn’t come from England. Fuck you.

Devo, outside Warner Bros. in Burbank, 1980

What was the first show you photographed?

The Motels at Madame Wong’s in Chinatown. They were cool. The early stuff was dark and moody and sexy and weird. And then Hong Kong Cafe opened up, and I was like, “Oh, there’s my home.”

And that was right across from Madame Wong’s, right?

You could hit them with a rock. In fact, Hong Kong used to run ads: “Right across the alley from Madame what's-her-name.” I only went to see a couple shows at Madame Wong’s. I always said it’s where new wave went to die.

So after you discovered Hong Kong Cafe, do you recall some of the first shows you started photographing?

I started going all the time right away. I was out at least four or five nights a week for five years, shooting shows and seeing shows. I was everywhere. I shot all of my live pictures with a 50mm lense. I was like two, four feet away from these people. No telephoto. I saw some clowns in the back of the hall with these three-foot-long lenses and a tripod and a drink, shooting Iggy at the Palladium. They were like 70 feet away from the stage, probably getting pictures of his nose hair sitting back here. Later, I realized that a 50mm lens is akin to human vision perspective, and there’s no distortion and it's immediate like that. I’m two feet away from H.R. from Bad Brains, I'm three feet away from Henry Rollins when I’m shooting these pictures.

Henry Rolins of Blag Flag on flatbed truck in Downtown LA, circa 1984

That's part of what’s so special about your photos, it feels like you were so immersed in the moment. Like you were either on stage or consumed in the pit, trying to keep your balance.

I was. The 50mm lens is what does that. I was right here. People shoot all this crap with a fisheye lens—the band looks 30 feet away and this guy’s nose is huge. It’s boring.

There’s something also about your photographic style that complements the music so well, the cinematic black-and-white mood you created around each artist.

Yeah, it's kinda like punk noir. I didn’t think about it. A lot of what I do is dark, but it’s funny. Like with my sculptures, they’re all dark, but they’re funny at the same time. It's kind of a weird dichotomy. Somebody was like, “You should shoot color, look at the girl with the pink hair.” That’s irrelevant, peripheral crap in my opinion. This is kinda wild and crazy and dark and angst-filled. It's got nothing to do with pink hair.

Bad Religion, circa 1980-81

Did you have some other photographers that influenced you at the time?

None. I was an art nut ever since I was a little kid. All I cared about was art. Growing up I studied all forms of applied arts: woodworking, sculpting, printmaking, design, ceramics. I never studied art history, I only paid attention to art that spoke to me. I could care less about...like, Rubens—he was a great painter, but doesn’t talk to me at all. I concentrated on the art and art movements that actually spoke to me or that I cared about. More modern art. I like art after the advent of photography in the 1800s, they started doing abstractions and things like that. Prior to that, I like some of the Egyptian art. I like Hieronymous Bosch and Albrecht Dürer, and things like that. After the late 1800s is when I started liking more art. The surrealists, the Dadaists, symbolists, constructionist stuff.

And all of those interests inspired your perception when you’re looking through a lens?

Yeah, that’s the background. I never studied photography, I think calling yourself an artist or a photographer is really ludicrous. It's like, “Who deemed that?” “Well, I did, I took a picture so I’m a photographer.” I always say history will tell. I always say I take pictures and I make things. Deeming yourself an artist is kind of totally hilarious.

“Somebody was like, 'You should shoot color, look at the girl with the pink hair.' That’s irrelevant, peripheral crap in my opinion. This is kinda wild and crazy and dark and angst-filled. It's got nothing to do with pink hair.”

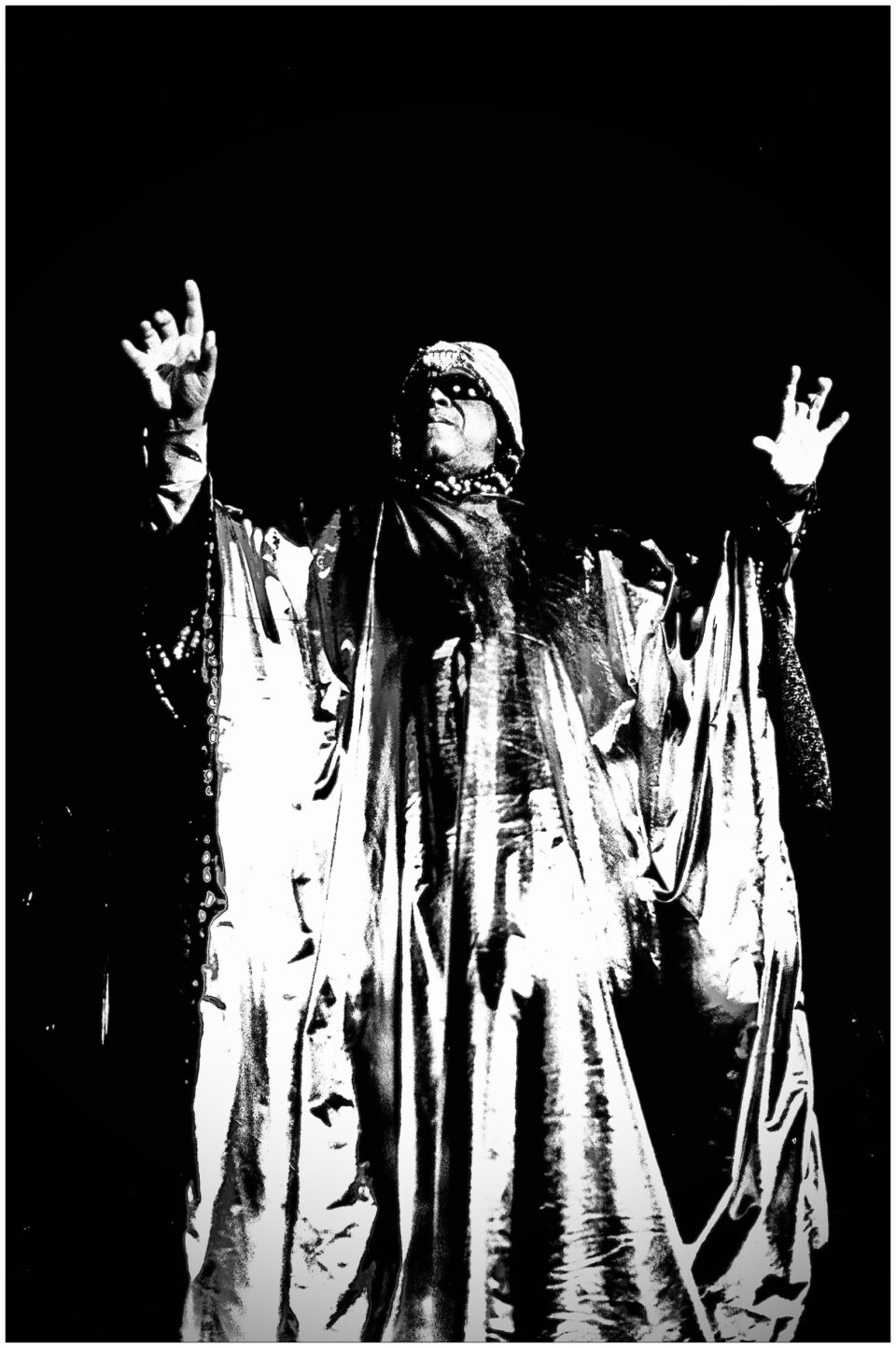

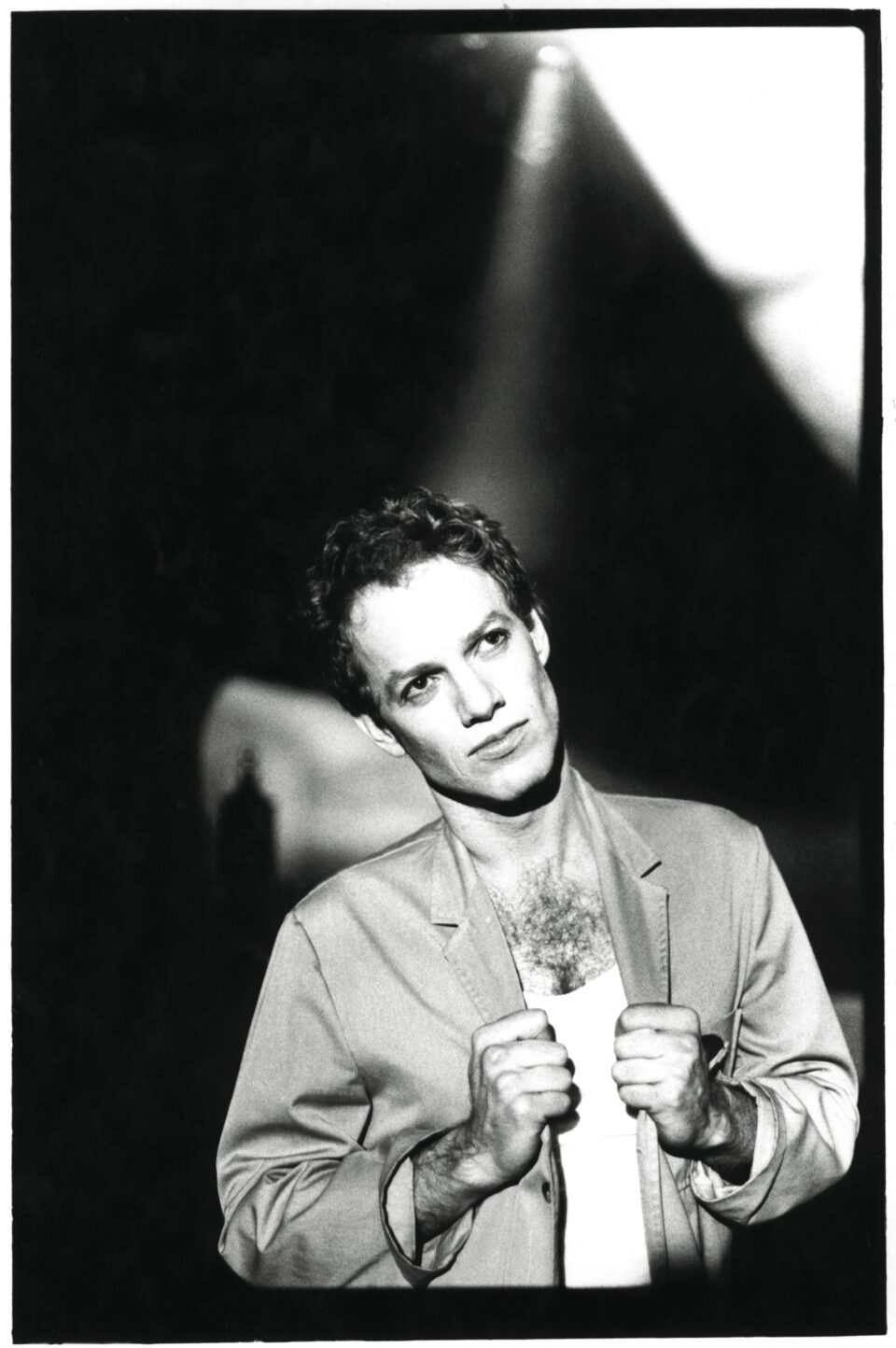

photo by Edward Colver

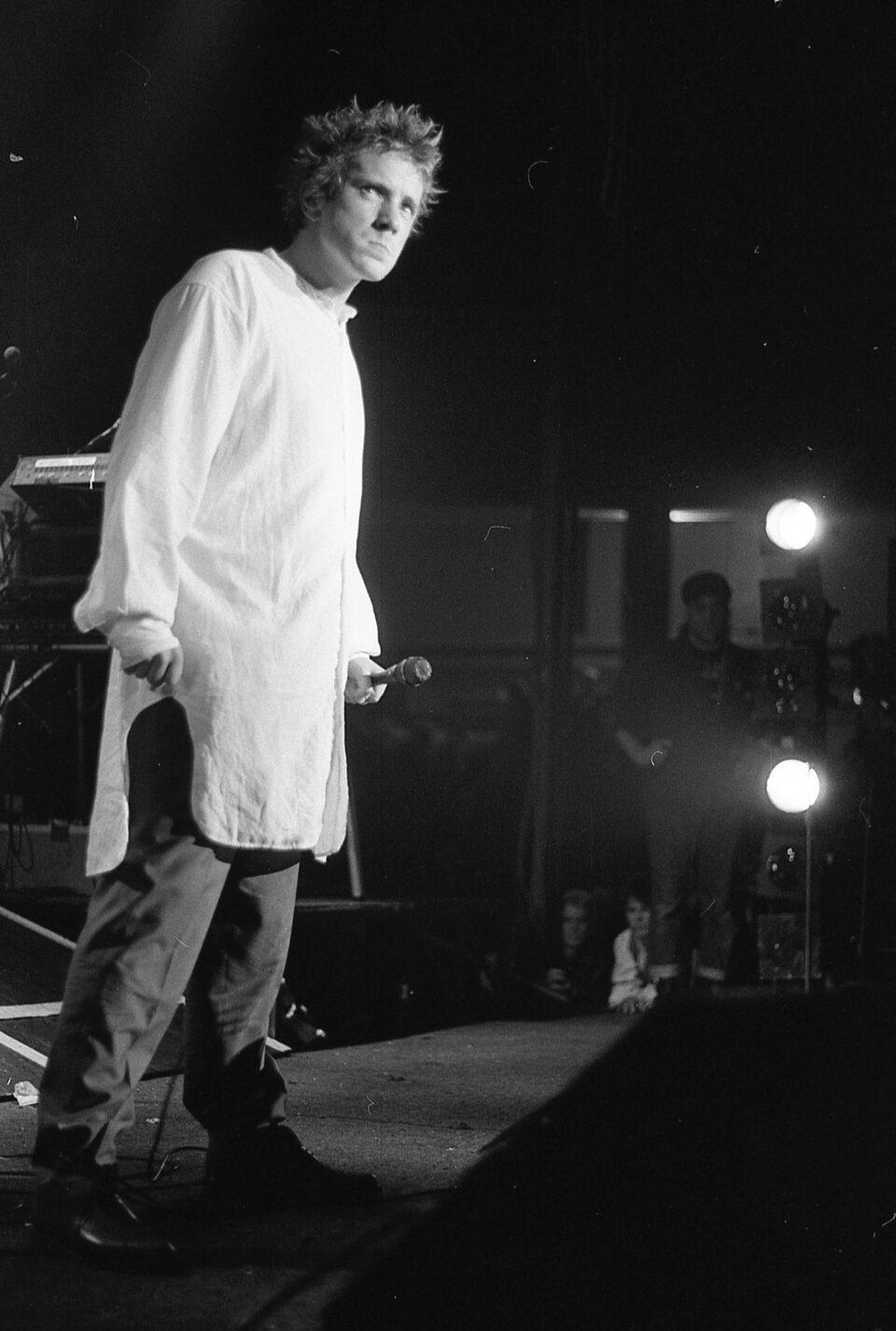

John Lydon of Public Image Ltd, Olympic Auditorium, 1980

Today, of course, everyone has a camera phone. Every show you go to, thousands of photos come out of it because everyone’s taking pictures. For these shows, you were one of the only people photographing them. What drove you to keep going back and taking photos?

What was happening was amazing. It was fun. I’m still life-long friends with a lot of these people. I was older than all of the punks. I was 29 in ’78. I was hanging out with teenagers and stuff like that. We got along just fine, it didn't seem like a gap, we could relate to each other. I did a lot of work in that scene and it’s like, the punks didn’t look in the phone book to hire a photographer. I was there. I did the Circle Jerks album cover and everybody liked that, and I did the [self-titled] T.S.O.L EP—I did the photograph and graphic treatment and typeset on that, and they still use those—they’re icons, you know? Which is amazing, it’s cool. So right away I was in the middle of it. I never asked for work. I never ran an ad. I never had a public phone number. I used funeral sympathy cards with my info on them for business cards. By the end of 1983, I’d worked on 80 punk rock records. If I wanted to get some work, I’d go to a show. “Oh hey, there you are.” Boom, I’d get work.

Who were some of the first bands you forged a strong connection with early on? Circle Jerks?

I shot live photos of them at the Whisky and they liked them, they wanted to use them on their record, and then they had me do their album cover. There’s talk that that was a spontaneous thing, that they thought, “Let’s just get everybody down in here and have Ed do a picture.” [But] I had color film with me, it was set up as a photoshoot. It wasn’t spur of the moment. I didn’t just happen to be there. I went to take the picture. That was a shitty, bad color slide. It was slightly blurred. Then [designer] Diane Sincavage turned it into a high-contrast print and overlaid it and did all of the colors. That was the first album cover I did.

Circle Jerks, backstage bathroom at Whisky a Go Go, circa 1980-81

Marina del Rey Skatepark, same day as cover shoot for Circle Jerk’s Group Sex album cover, 1980

The shot you got that ended up being the cover, how did you capture that photo?

I was on a ladder next to that pool with a bunch of skateboarding punks and drunk punks all running around like chaos. It was kind of scary. Bill Bartell—rest in peace—from White Flag is wearing this shirt that says “Punk Sucks.” People think it got censored out. I think it would have been great if they kept it in there. But it just disappeared with the contrast from the stat print. It wasn’t censored out, it was just printed that way.

You captured so many scenes of police activity outside of shows, like the Black Flag/D.O.A. “riot” at the Whisky or the police presence at the Decline of Western Civilization opening. We’ve seen this over and over again, where cops show up and the situation gets worse.

Yeah, it’s like if you weren’t there nothing would be happening. With the Black Flag/D.O.A. riot at the Whisky, I knew the punk that threw a beer bottle at a cop car, and that set the whole thing off. I have photos of the intersection of Sunset and San Vicente, where it was all blocked off with cop cars. Licorice Pizza is in the background, which is pretty funny.

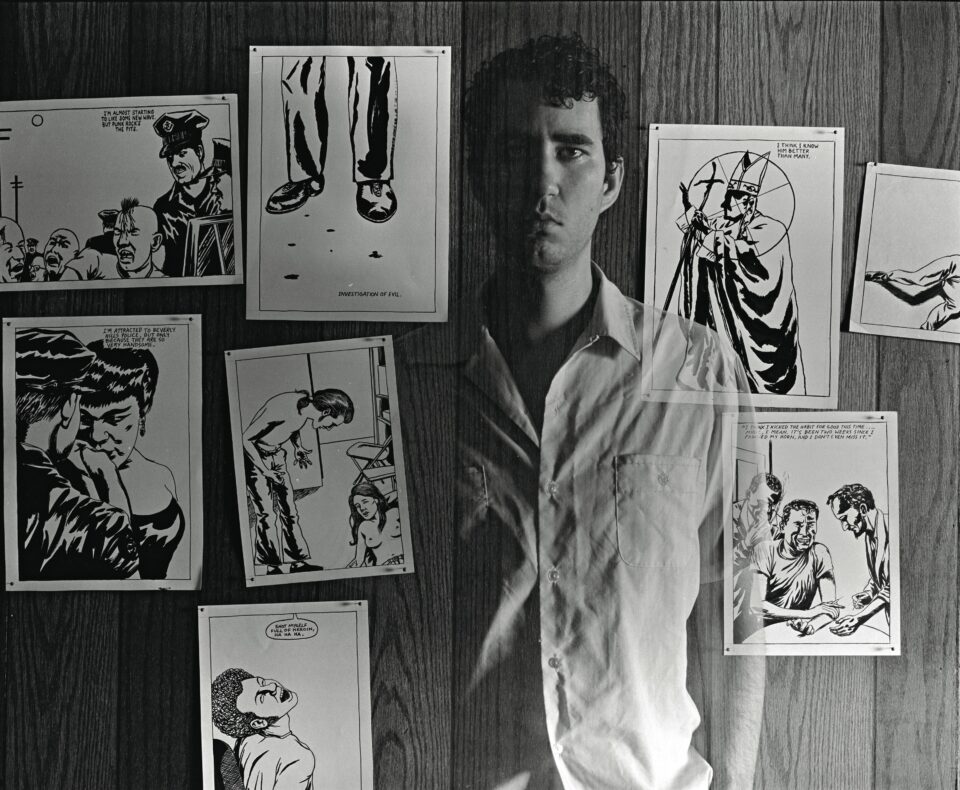

Raymond Pettibon, 1983

How many of those shows did the police actually need to be at?

I would say none of them that I saw. Nothing would happen until they showed up. Black Flag and [former LA police chief] Daryl Gates had a big war, no thanks to Raymond Pettibon and his artwork. And Daryl Gates was kind of a draconian type. It was interesting when I shot all the cops on Hollywood Boulevard for Decline of Western Civilization in 1980. [Director] Penelope [Spheeris] goes, “I can’t use that stuff, nobody would ever book my movie,” but now she loves that I was there and captured that.

What are some of your memories of the Starwood?

It was fun. It was similar to the Whisky for me. The Whisky was a bit smaller.

The Adolescents, Starwood, 1980

What are some of the shows that stand out from there?

The Weirdos, The Alley Cats, The Blasters, the Germs, Fear. I was at the Hong Kong when they closed it down and Fear played. And then I was at the Starwood the night that Fear played when a bouncer got stabbed and then they closed it down. Fear closed down two of the clubs.

Fear seemed to attract that.

Yeah, that’s ’cause everyone was going off and saying stupid stuff and being obnoxious. That spitting shit that was going on for a while was the most obnoxious thing I've ever seen. Lots of crowds where Lee Ving starts spitting at the crowd and the crowd starts spitting back.

Tom Waits, on the set of “The Cutting Edge” at The Travelers Cafe, 1985

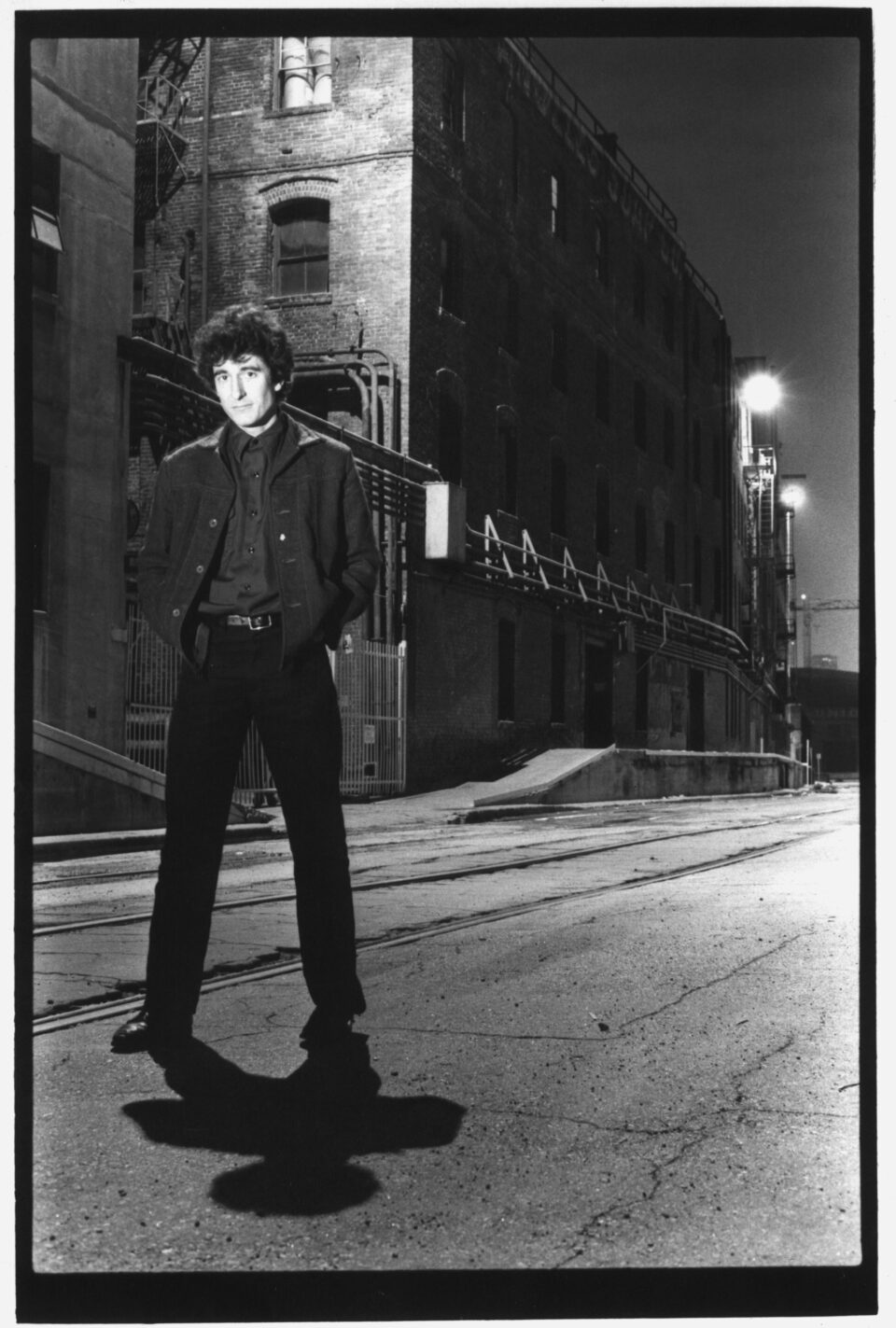

Stan Ridgway, Downtown LA, circa mid-’80s

Danny Elfman, on the set of “Weird Science”

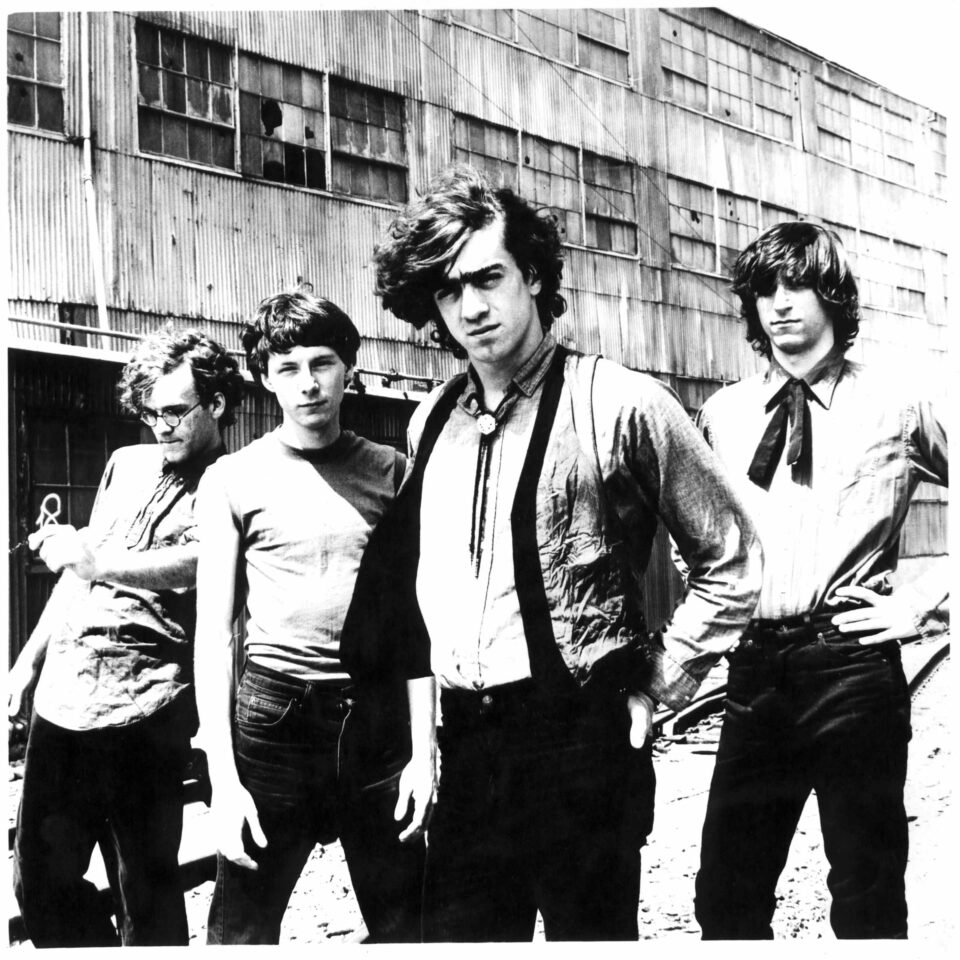

R.E.M, Downtown LA, 1984

So around 1984, did you hit a moment where you were like, “I’m done, I don't need to go to five shows a week?”

Yeah, kind of. I got my first studio in ’84 and you know thrash kinda reared its ugly head, and I wanted to make a living off of photography, and I got a studio so I’d be taken seriously as a photographer. I thought I could make it happen, and it did.

Around this time you were also shooting a lot for I.R.S. Records.

Yeah my friend, Carlos Grasso, the art director, he loved my work and he started using me and I did a lot of work for I.R.S. I was the third person hired on The Cutting Edge [an MTV show produced by I.R.S., which ran from 1983 to 1987] crew.

Working with I.R.S. and on The Cutting Edge, you started shooting a lot of different kinds of artists.

Yeah I was photographing R.E.M., Lords of the New Church, The English Beat, Wall of Voodoo, The Alarm.

Ice Cube, circa 1992

The Cutting Edge was such a great show at the time.

Carlos did that show. I never really saw it. I don't think I was watching television at all at the time. I saw little bits in the office sometimes. When I shot the photos of Nick Cave for the filming session at the Chateau Marmont, he tried to read a poem nine times, fucked it up every time ’cause he was drunk, and it never got aired. I shot Tom Waits on the set of Cutting Edge. When I photographed that Ice Cube portrait [in 1990], I spent one minute shooting that, and I’m not exaggerating. I did two Polaroids. That got used for his Greatest Hits. I did it in 60 seconds and the art director said it was the definitive Ice Cube picture.

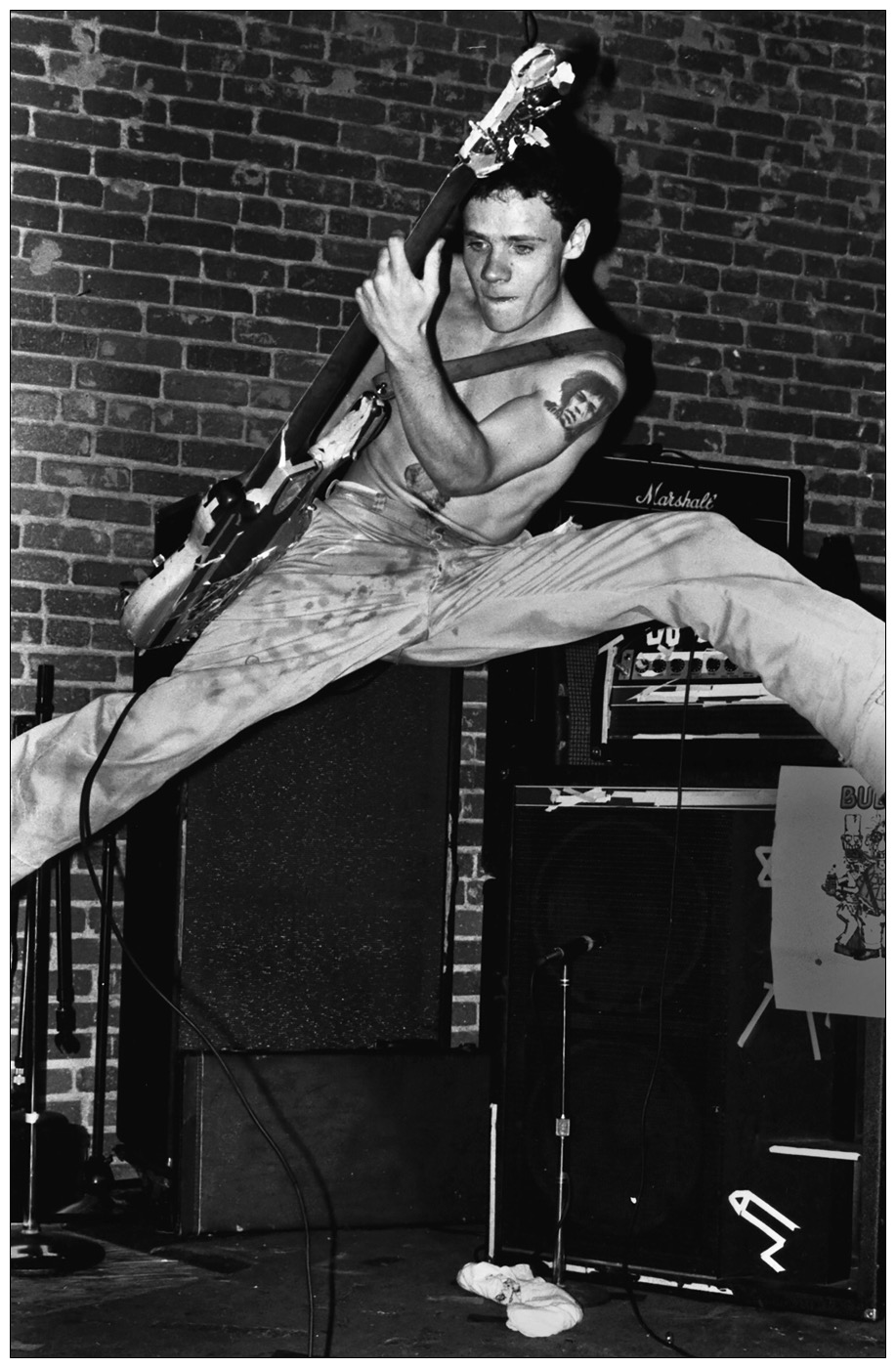

Another iconic photo of yours, your stage diving shot of Chuck Burke, has certainly taken on a life of its own.

That was at Perkins Palace in Pasadena, July 4, 1981. When I was saying I was right next to these people, I was onstage with my friends, I was up front or right onstage. The pictures of H.R., I was right in the middle of the stage taking pictures. I didn't think about it, I was just doing my thing. I could at that time; nowadays someone would knock you off, you couldn’t do it.

What was the show?

That was Adolescents, D.O.A., and Stiff Little Fingers. And I took the photograph during the Adolescents set of Chuck Burke doing a forward flip off the stage. People say it’s a backflip, it’s a forward flip.

Chuck Burke stage-diving at Perkins Palace, 1981

Did you find out later who he was?

Yeah, I met him the next night. I had already developed it and printed it, and I was actually in the process of shooting stuff for Wasted Youth’s first album, shooting some live shows and stuff, getting some stuff together for their first album. I called Danny [Spira] up, I said, “Wait ’til you see this picture I got last night.” I took an 8x10 I made of it with me to a show the next night, I think it was Angry Samoans or something. I fell into some kids, and one of them was Chuck Burke. I never recall seeing him before or after that. He was like “Hey, that’s me!”

So you haven’t heard from him since?

I have his info, but I haven’t bothered him. There was some guy on Facebook claiming it was him. I was like, “You’re full of shit.”

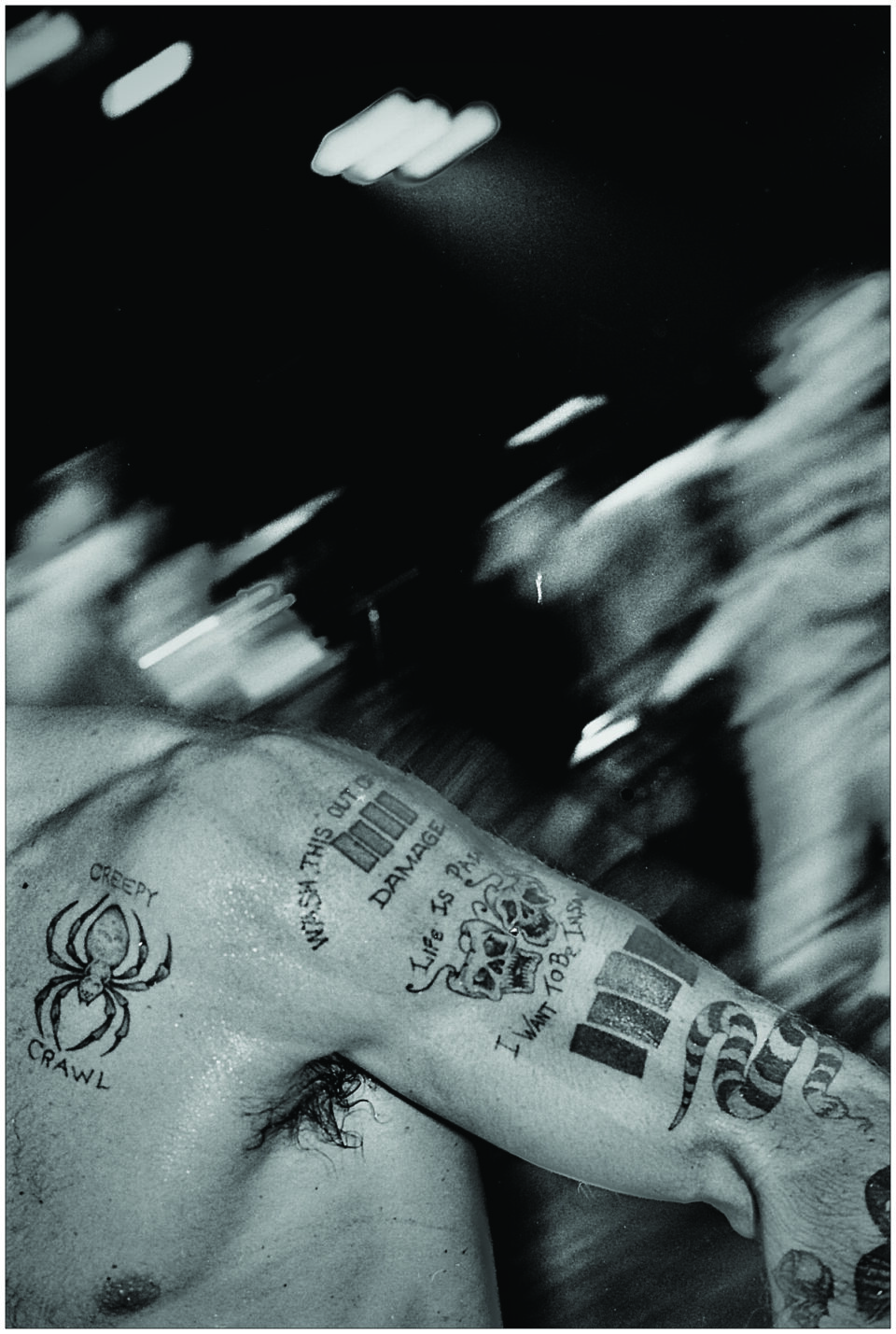

Your cover photograph for Black Flag’s Damaged is another shot that’s been copied and parodied many times over the years.

You know it’s funny, shit like that used to piss me off, and now I save them and laugh at them. And it kind of iconicized my image that much more.

Henry Rollins, Damaged cover photo, 1981

I think people always look at that image in awe that Rollins is shattering that mirror, but it was staged, right

Yeah, I had to. If he just went blam there’d be no blood on his hand. I had to set it all up.

What did you use for the blood?

What I came up with was red India ink, dishwashing soap for consistency, and instant coffee for color and consistency, and it came out perfect. Back then you couldn’t just go buy stage blood. There could have been a place in Hollywood that sold it, but I didn’t know about it so I made it. It looked beautiful, it looked like real blood in the color photo and in the black-and-white.

So tell me about the next book you’re working on.

I want to do this definitive punk thing. I want it to be this bible of the LA punk scene. I want to put The Rim Pests, The Plague, The Decadent, all these other bands [no one knows]. I want at least something of them in there, they were all part of it. I want to do, like, 30 pictures of Dead Kennedys, 25 of T.S.O.L, a bunch of stuff. Not just one or two. That’s the way I’m looking at it. Here they all are...like, everything worth a damn. FL