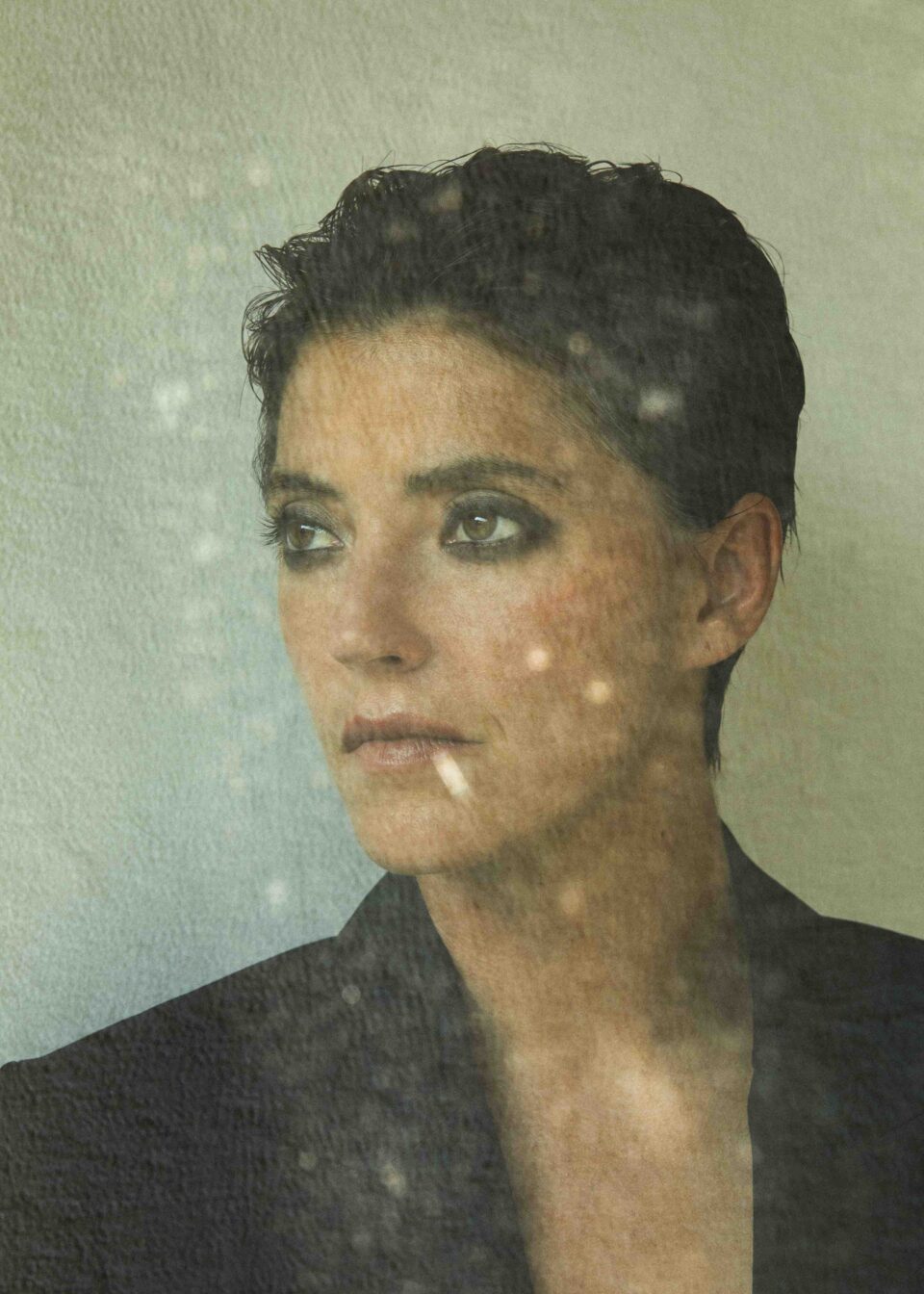

The emotional scale of We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong, Sharon Van Etten’s sixth album, initially threatens to overwhelm. The songs veer from delicate frailty to volcanic release, bulldozing unblinkingly through subject matter including but not limited to familial turmoil, emotional distance, death, civil unrest, and fiery apocalypse.

Which is why it’s more than a little disarming to hear Van Etten reveal the genesis of the album’s thematic core to be the 1993 coming-of-age baseball comedy The Sandlot. Her family kept returning to the film for comfort during the pandemic’s most uncertain days; on their umpteenth viewing, one particular moment resonated. It comes as the film’s adolescent protagonists are attempting to retrieve a baseball signed by Babe Ruth, currently stranded in a backyard guarded by a particularly uncompromising English Mastiff.

Over Zoom, Van Etten describes the scene in which the boys attempt to retrieve the ball with a vacuum, culminating in an explosion that forces the crew to weigh a course correction. “He’s covered in dirt, and he shakes himself off and he looks at his friends and he says, very deadpan, ‘We’ve been going about this all wrong,’” Van Etten tells me. “It was the point in the pandemic where you feel like you’re hopeful and then something else happens. There was something so simple about it that got me all choked up and I wrote it down. And from all the songs I recorded from the last couple of years, with that umbrella as my mantra, it helped me pick out the songs that I thought fit under that category.”

“The way I cope with stress or depression or anxiety or whatever it is I’m managing, I tend to sing—even if it’s nonsense, if it’s just stream-of-consciousness, it always makes me feel better.”

It's that need for a reset that animates We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong, an album with no shortness of unease that nevertheless is notable for its underlying strains of optimism. Its thematic terrain, heavy as it is, reflects the grim conditions under which the album gestated. The title of Remind Me Tomorrow, Van Etten’s staggering 2019 LP, was a reference to that error message that permits us to avoid updating our computers in perpetuity; it reflected her manic schedule and inability to focus on essential priorities. With All Wrong, the ground beneath Van Etten has shifted; she suddenly has all the time in the world to focus not just on the most pressing of her priorities, but all of them. And she recognizes she has some work to do.

At the start of the pandemic, Van Etten and her family were only a few months removed from relocating from New York to Los Angeles. When the world shut down, she was still finding her footing in a new city, but the circumstances granted her some additional breathing room. “We would have been in an apartment in Brooklyn with a toddler and I wouldn’t have had a place to work,” she explains. “So in a lot of ways we felt very fortunate with the timing, because we did have an outdoor space.”

The bulk of the album originated from those early days of the pandemic, with some key exceptions. “There were two songs that I had written prior to moving to California, and I didn’t want to share them with the world yet because I thought they were too heavy,” she says. “One was ‘Darkish,’ and one was ‘Far Away.’ Because one deals with the end of the world and the other one deals with dying. So I was like, ‘Well, maybe I’ll wait on those.’ But it’s funny that in the collection of the work I made the last couple of years, they seemed lighter in the mix.”

“People don’t talk about albums anymore in the way that they used to. It’s like when you see a trailer when you feel like you’ve already seen the movie. I wanted to give people permission to sit down and enjoy it in its entirety.”

Everything else, though, was developed during lockdown, and often originated as private therapy, a means of treading water as the world around her crumbled. “The way I cope with stress or depression or anxiety or whatever it is I’m managing, I tend to sing—even if it’s nonsense, if it’s just stream-of-consciousness, it always makes me feel better,” Van Etten says. “And most of that shit I don’t share with people, because it either doesn’t make any sense or it’s too heavy or it’s not relatable or universal. And that’s just for me, I file it away. Maybe I can edit it later [to the point] where other people can connect with it.”

As Van Etten began to shape the album, she couldn’t shake the sense that a different release strategy was warranted. She ultimately opted to share the album all at once, with no songs revealed in advance of the release date; she believed the slow-drip promotional strategy could cheapen the experience of digesting the album holistically. “People don’t talk about albums anymore in the way that they used to. Talking to fans, being a fan, it’s like when you see a trailer when you feel like you’ve already seen the movie. I wanted to give people permission to sit down and enjoy it in its entirety.”

She did release two singles ahead of the album, “Porta” and “Used to It,” neither of which was included on the final tracklist. But she bristles at the perception that these songs are inferior. “People assume that B-sides are throwaway songs that were the fluff of the record. For me, it’s a struggle every time, because I record all these songs and I love them all,” she tells me. “Sometimes there’s just one song that plays this one role and there’s two songs that you have to pick from because they fill that role. ‘Porta’ was one of them; that would’ve been where ‘Mistakes’ was on the record. But I just thought it was such a beautiful song. ‘Used to It’ would’ve been where ‘Far Away’ is.” Rather than let these songs languish on a hard drive somewhere, she released them to signal to fans that music was forthcoming without revealing any of the finished product.

“I pepper these little messages throughout the record that are to my kid that I know he can’t understand yet, and that maybe one day he’ll listen back to it and hear the apologies or the acknowledgements, knowing that it’s hard right now.”

This speaks to the care with which Van Etten assembles her work. “I love sequencing. I think there’s an art to it. I think transitioning from song to song—from the mood, the pivots, the fade-ins, the fade-outs, the key signatures, the tempos, the emotions from one song to another, pulling and playing with the listener—I have so much fun doing that.” Each new phase of We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong signals this level of attention without ever feeling stuffy or overdetermined.

Take the mid-album centerpiece, “Born.” This started off as one of Van Etten’s private therapy sessions, a song she made about a situation with a friend that was gnawing at her. But then, Van Etten says, “it started spiraling into this bigger tension that’s more global. It represented the time that had passed since the incident with the friend to what was happening now, and how meaningless that one incident was in the context of what’s actually happening in the world.” You can hear the song uncoil into something grander in real time, building to its towering climax, a tidal wave that subsumes the modest ballad that preceded it.

While Van Etten does make space for levity (“Mistakes” is “a song about being a bad dancer and being OK with it”), the above dynamic is a recurring motif throughout the album: white-hot emotion boiling over into cinematic release. Opener “Darkness Fades” is an ominous march that builds steadily, with Van Etten at one point invoking the wildfires that ravaged California shortly after she moved there. “Come Back,” one of several instant hall-of-fame SVE songs on the album, aches to its bones for reunion with an unnamed subject; its relative restraint out of the gate makes way for Van Etten’s fiery howl of a hook.

“Home with Me,” which Van Etten wrote for her five-year-old son, is more understated but no less impactful. Her son loves her music, but he’s only beginning to process the nature of Van Etten’s celebrity. That doesn’t stop her from feeling guilt about the nature of her job and the distance it can create with her loved ones. “I pepper these little messages throughout the record that are to my kid that I know he can’t understand yet, and that maybe one day he’ll listen back to it and hear the apologies or the acknowledgements, knowing that it’s hard right now. It’s about to be super hard,” she says, referring to her upcoming tour. “It’s not that I don’t feel guilty, but it’s also hopefully going to help shape him and how he connects with the world and how he connects with people and how he looks at relationships in his life.”

“During intense times, you realize who your real friends are. There are those people you can rely on, and [Angel Olsen] became a lifeline for me during all this.”

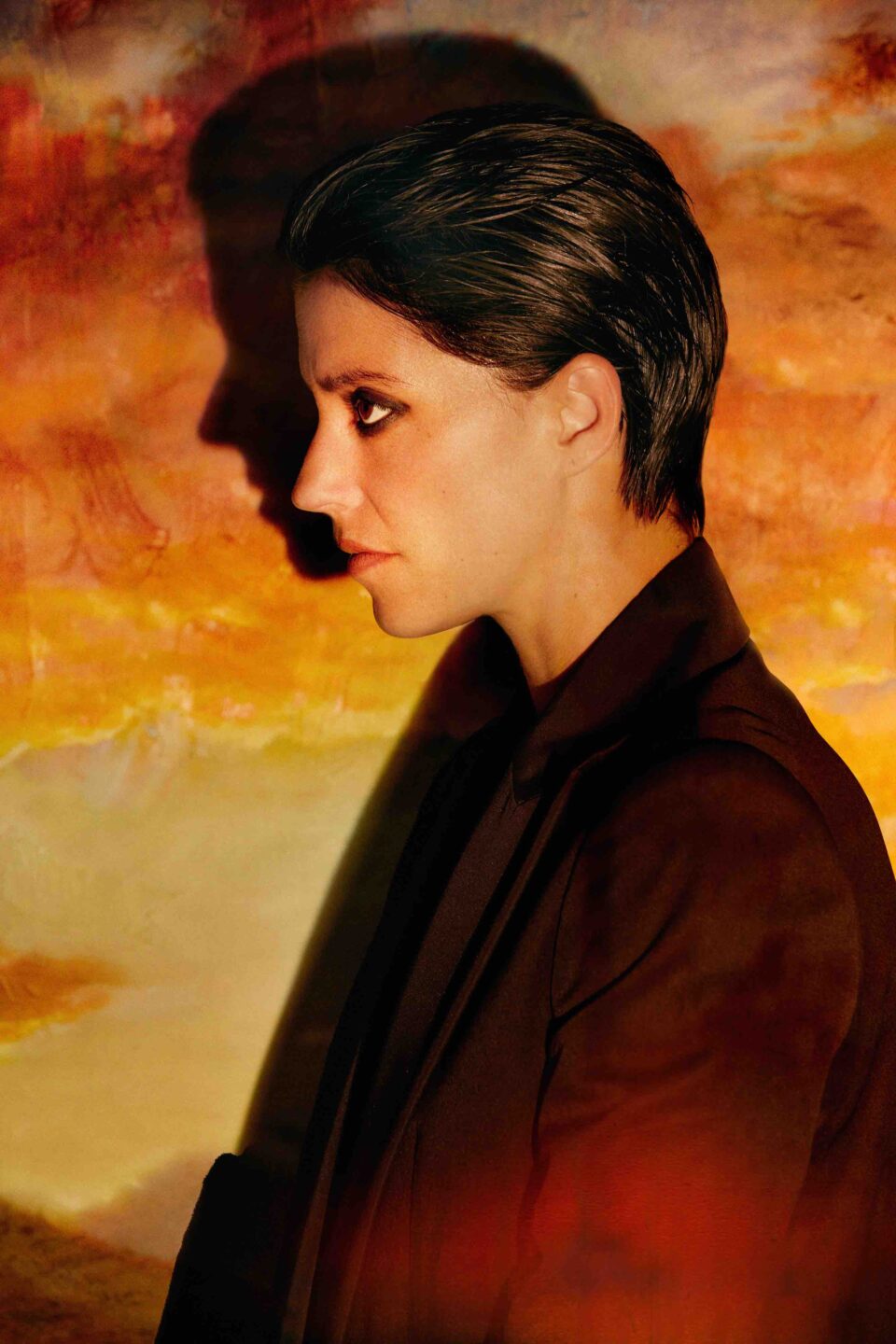

Though Van Etten is dreading the distance from her family, she seems energized at the prospect of hitting the road with Angel Olsen, with whom she collaborated on last year’s anthemic single “Like I Used To.” They became closer during the pandemic, Van Etten says: “During intense times, you realize who your real friends are. There are those people you can rely on, and she became a lifeline for me during all this.” Van Etten shared a skeletal early iteration of “Like I Used To” with Olsen for feedback, planning to potentially gift the song to her since, by Van Etten’s own estimation, it more closely resembled Olsen’s style. Olsen loved the song, and her initial feedback snowballed until the song evolved into a full-fledged duet. “She was just so wonderful to work with and she’s such a beautiful person. I hope we can do more of that down the road.”

Matters of human connection are the beating heart of We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong, and much of its duration is spent navigating the complexities of those connections when confronted with distance and strain. But it is a fundamentally hopeful album, never defeated: “It’s not dark, it’s only darkish,” goes one of the album’s most self-referential refrains. “In real life, I’m a Pollyanna. I’m very optimistic. The struggle was being in a moment where I wasn’t,” Van Etten says, speaking of the mental ruts she fell into throughout the pandemic. “But then you have to move on, you have to get through that, acknowledge it, deal with it. If you don’t address it and you’re stagnant, not a lot of change is going to happen. So I think that was my struggle. If I didn’t write to get through it, I probably would’ve stayed there.” FL