We’re all different people than we were before COVID. For many of us, the changes have been radical. Stuck indoors, we started taking longer, harder looks at ourselves, and while the world outside spun increasingly out of control, we tried to regain a sense of groundedness through reinvention. We cut our hair or grew it out. We broke up with partners. We started new careers, hobbies, podcasts. We joined quasi-mystical conspiracy cultists or became radical leftists. We got sober. We transitioned.

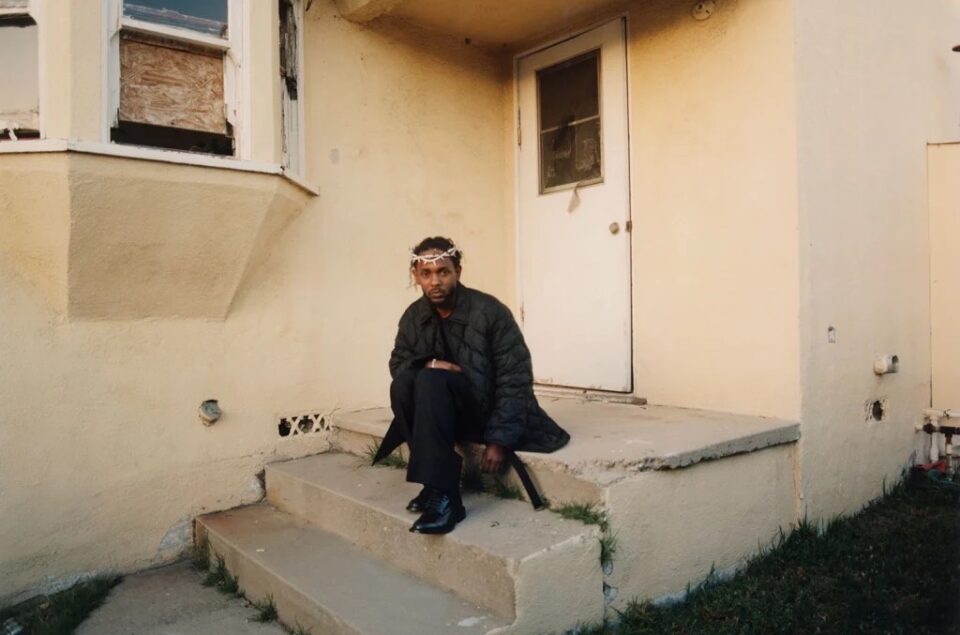

Even rap superstars have been feeling the pressure. “I’ve been goin’ through something,” are the first words we hear from Kendrick Lamar on his fifth full-length. Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers is an 18-track double-LP that lets us look over Kendrick’s shoulder at what he saw during his own deep look in the mirror: How fame had blown his ego up to toxic proportions. How his chronic pussy-hounding had jeopardized his relationship with his long-term romantic partner. How he’d fed his material greed instead of confronting the insecurities beneath it. We watch him break down and finally start doing the hard work on himself that he’s been avoiding.

We also meet the person who emerges after he embraces therapy, the teachings of celebrity New Age spiritual philosopher Echart Tolle, and the nutritional regimens of controversial cult herbalist Dr. Sebi. The new Kendrick is more honest, vulnerable, and, ironically, humble, more willing to see himself from the perspectives of other people which might not be as flattering as his own, or those of the millions of fans and Pulitzer nominating committee members who hold him up as rap music’s savior and America’s conscience. He’s still as righteously angry as he was on To Pimp a Butterfly, but he’s shifted his anger from the specific systems of racial oppression in America to the broader spiritual deficit in our society that prevents us from helping each other. The real pandemic, he’s saying, is the lack of love we have for anyone but ourselves, and the love we have for ourselves often isn’t healthy.

Mr. Morale follows in the footsteps of albums like John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Eminem’s Marshall Mathers LP, career-defining works by superstar voices of a generation who reached the highest possible levels of global celebrity and found out that money, fame, cars, and sex on demand couldn’t heal their souls, then turned the subsequent reckoning and rebuilding into complex but vulnerable music. Like those albums, it’s an often-unsparing self-portrait by an artist talented enough to justify their stratospheric fame, working at the peak of his abilities.

Mr. Morale lets us look over Kendrick’s shoulder at what he saw during his own deep look in the mirror: How fame had blown his ego up to toxic proportions. How he’d fed his material greed instead of confronting the insecurities beneath it.

It’s a complex masterpiece, one that demands deep engagement and front-to-back listens. Kendrick has somehow become an ever better writer and rapper in the nine years since he bodied an entire generation of emcees on “Control.” He’s always been a lyrical artist, and on Mr. Morale the writing reaches the level of a Kerry James Marshall painting, piling up layers upon layers of references to pop culture, LA lifestyle, and spiritual texts, woven together in a way that feels deeply personal. He doesn’t just deliver punchlines, but turns them around and inside out, like the run-on imagery in “Rich Spirit” that begins with fist-bumping frat bros and winds through waves of paranoia before landing on an endorsement of fasting as a spiritual exercise.

He’s also the type of artist who pulls his collaborators up to his level—particularly his longtime beatmakers Sounwave and DJ Dahi, who make a game out of effortlessly deconstructing and recombining hip-hop styles, like mixing 2012 motivational rap with 2022 UK drill on “N95,” or recreating DJ Mustard’s signature style with a luxury sound palette on “Rich Spirit.” (Sometimes they ditch beats altogether, in favor of neoclassically inspired piano and choral pieces that suggest a possible direction for rap music as a form if and when it evolves past hip-hop as a style.)

It’s also a messy album in many ways, which feels true to our very messy COVID era. Never one to pull a punch, Kendrick spills his own tea in high volume and vivid detail, about his cheating, his selfishness, his prejudice, his general egotism—he even calls himself out for the unhealthy catering at a Christmas toy drive he helped put on in Watts. On “We Cry Together,” an entire five-and-a-half-minute dramatic dialogue between himself and Zola star Taylour Paige, he gives us an uncomfortably close look at the kind of fights he presumably had with his partner, Whitney Alford (who, to add to the drama, also appears as a narrator on the album’s interstitials). Kendrick’s spiritual breakthrough hasn’t entirely eliminated his ego, though, and he’s messy even when he’s promoting positivity. “Shut the fuck up when you hear love talking,” he proclaims on the retro-soulful “Purple Hearts.” “If God be the source, then I am the plug talking.” There’s also the dicey proposition of prominently featuring Kodak Black—who has a documented history of violence against women and pled out a rape charge last year—on confessional songs that offer up trauma as a partial explanation, if not an excuse, for his acts.

Trauma shows up frequently on Mr. Morale—how it shapes us, how it influences the way we treat others, how we can resolve it. “Trauma” is, of course, the most overused pop-psychology buzzword of the moment, and the subject has become almost as inescapable on playlists as it is on social media—particularly in hip-hop, where suicidal ideation and compulsive pleasure-chasing have become the default. At its core, though, it’s really an album about forgiveness, which isn’t so popular at the moment. As our lives have become increasingly influenced by social media, we’ve become more polarized in our thinking, and across the political spectrum we’ve become more prone to holding rigid ideals of how people should be and act, and more willing to call out, shout down, or ice out people who violate them.

The real pandemic, he’s saying, is the lack of love we have for anyone but ourselves, and the love we have for ourselves often isn’t healthy.

Self-improvement infographics—whether girlbossified or sigma-male-slanted—encourage us to simply drop people from our lives if they aren’t giving us what we want. We’re a people who pay a lot of lip service to “healing,” but would rather ghost than do the hard work of manifesting it. “Cancel culture” may not be the monolithic menace that Trumpists, TERFs, and standup comedians are trying to sell it as, but it’s also true that in online culture, especially toward the left, there is social value in ostracizing people at the faintest hint of transgression, without offering them the path to redemption.

Forgiveness is messy. It doesn’t give us the same rush of moral clarity and righteousness that quote-unquote canceling someone offers. It takes hard work and a lot of time. Real forgiveness isn’t just letting someone off the hook; it’s an active process that pushes us outside our comfort zones, where we have to interact with people who harmed us, put ourselves in the shoes of someone we don’t like, ask ourselves questions we’d rather not confront. Can we forgive the person who’s hurt us? Can we understand the traumas that underlie their behavior, or even learn to sympathize with their experience? Can we forgive someone like Kodak Black, who details his own traumas in a spoken-word segment on “Rich (Interlude)”? Can we forgive R. Kelly, who, as Kendrick reminds us late in the album on the track “Mr. Morale,” was himself the victim of childhood sexual violence? Can we forgive ourselves?

On Mr. Morale, he argues emphatically, compellingly, that we should—or that we should at least be open to asking these questions. The spiritual guidance Kendrick offers on the album can be hard to swallow, but what he’s saying seems to genuinely come from a place of love. If we can’t treat each other right, he seems to argue, if we don’t allow ourselves to forgive, then we miss opportunities to heal, and to help others heal. We can’t solve the issues of systemic oppression, he suggests, if we’re not able to love each other. To get us there he goads, pleads, models better behavior, and occasionally flat out bullies the listener. He also makes use of one of his greatest gifts: his ability to provoke.

Kendrick may be a more enlightened being these days, but he’s still one of rap’s all-time great diss writers, able to zoom in on someone’s most vulnerable spot and poke it in a way that feels not only personal but discomfitingly intimate. (I can only imagine Kanye seething over the phenomenally shady “Father Time” line, “When Kanye got back with Drake, I was slightly confused / Guess I'm not mature as I think, got some healing to do.”) On Mr. Morale he makes the brave (or self-destructively cocky) decision to take aim at the listener for, as he sees it, our own flaws, whether they’re spiritual complacency or engaging in moral hypocrisy online. “N95” opens with a reproachful list of behaviors we need to give up. “Take off the fake deep,” he commands, “take off the fake woke, take off the, ‘I’m broke, I care.’” Get off the internet, he harangues us. Stop obsessing over material things like luxury fashion labels. Do better.

Kendrick makes the brave (or self-destructively cocky) decision to take aim at the listener for, as he sees it, our own flaws, whether they’re spiritual complacency or engaging in moral hypocrisy online.

There are subtler provocations, too. Some of his decisions seem like they were made to intentionally rile up woke moral purists, the same people who raise “intelligent” artists like Kendrick up to savior status. Hence the Kodak features. Hence “Auntie Diaries,” a string-backed ballad where Kendrick recounts his complicated relationships with two trans relatives and his own homophobic and transphobic behavior, using the wrong pronouns for both family members, using one of their pre-transition names, and over the course of the song saying the word “faggot” 10 times.

Kendrick isn’t ignorant, and he doesn’t do shock value. I think he’s getting things wrong on purpose, not to trigger us for his own entertainment, the way Kanye seems to, but to force us to ask ourselves the questions he wants us to. He’s daring us to forgive him, provoking us to see if we can look past what he gets wrong to see what he’s doing right. Because behind the misgendering and deadnaming, “Auntie Diaries” is an incredible example of how to be an ally to trans people: Kendrick listens to trans people, accepts responsibility when he’s wrong, stands up to a figure of power to make space for a trans person, and, most importantly, he loudly, publicly, and emphatically declares his love for trans people in a context where there is actual social risk to doing so.

As a trans person, I don’t care if Kendrick says “faggot” or not (not that I don’t skip “Auntie Diaries” when it comes on; I get that word aimed at me enough as it is). I care that he’s stepping up for us. Etiquette isn’t the same thing as justice. Neither is “visibility,” “inclusion,” or “awareness.” The crisis for trans people in America isn’t that people aren’t using the right pronouns; it’s that there’s a war on our right to exist, and the people who claim to be on our side are too focused on optics and not enough on fighting. I’d rather have one person like Kendrick who’s willing to risk something for us—even if he fucks up sometimes—than a thousand self-identified allies who think posting about trans rights on IG is the same thing as doing something.

Behind the misgendering and deadnaming, “Auntie Diaries” is an incredible example of how to be an ally to trans people: Kendrick listens to trans people, accepts responsibility when he’s wrong, stands up to a figure of power to make space for a trans person, and, most importantly, he loudly, publicly, and emphatically declares his love for trans people in a context where there is actual social risk to doing so.

Mr. Morale doesn’t get everything right. Like a lot of privileged people talking about injustice, his arguments can be heavy on false equivalencies (like on “We Cry Together,” where he compares toxic masculinity’s encouragement of predators like Harvey Weinstein to female R&B singers not featuring each other on their songs). But we shouldn’t need people or the things they make to be 100 percent correct 100 percent of the time. To paraphrase one of the most valuable cliches in 12-step recovery, we should value spiritual progress rather than spiritual perfection. Twelve-step groups don’t kick you out when you relapse; they pull you in closer, give you even more support, keep you on the path of progress instead of pushing you away for not being perfect.

If we’re going to have any hope of succeeding in the fight for the rights and dignity of oppressed people, we need to be able to find the same kind of patience with each other, even if we do or say things wrong along the way. At one point during the weeks of marathon listening I’ve given Mr. Morale, I opened up bell hooks’ All About Love and found this quote: “All the great social movements for freedom and justice in our society have promoted a love ethic.” And we can’t live a love ethic if we’re not willing to do deeper, tougher work than sharing infographics or adding to a Twitter pile-on.

Is that possible? Of course it is. Can we pull it off? That remains to be seen. But there are millions of people listening to Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, and who will continue to soak up what Kendrick’s saying. Out of those millions, how many will actually do the hard work Kendrick’s asking us to do? Who knows, maybe it’ll be enough. FL