Of all the sacred and secular poetic classics that the enigmatic Leonard Cohen has committed to the tower of song, none is considered to be as potent and poignant as “Hallelujah.” You could argue for days that “First We Take Manhattan” is wryer, or that “Bird on the Wire” is more sheerly poetic, or that “Amen” is as holy as “Hallelujah,” yet more musically complex—but it matters not. The song has become that rarified thing: a classic that touches all from the cradle to the grave, with its branding as the soundtrack to weddings, births, and funerals well secured.

From his original sanctified version on 1984’s Various Positions (an album unreleased in America upon its recording, with Columbia’s label president famously saying, “Leonard, we know you’re great. We just don’t know if you’re any good”) to Cohen’s own more secular versions, to the history of artists who covered it (from Bob Dylan to Jeff Buckley, Rufus Wainwright to Brandi Carlile—not to mention the casts of American Idol and The Voice), the journey of “Hallelujah” is as epic as the song itself.

Premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival with a theatrical release in July and a companion anthology available digitally now (with CD and limited-edition translucent blue vinyl releases due out October 14), Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine’s documentary feature Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song puts forth more questions, bleak and buoyant, than it answers. As Cohen was an artist who never saw reason to over-explain his myth or his magic, the enigmatic aspects of his craft are mostly what live on with his legacy. And with as many opinions as to the song’s might, the riddle grows deeper and more mysterious. Two of the many people interviewed for the documentary—journalist Larry “Ratso” Sloman and vocalist/collaborator Sharon Robinson—offered their own various positions on Cohen and “Hallelujah” when questioned after the documentary’s screening.

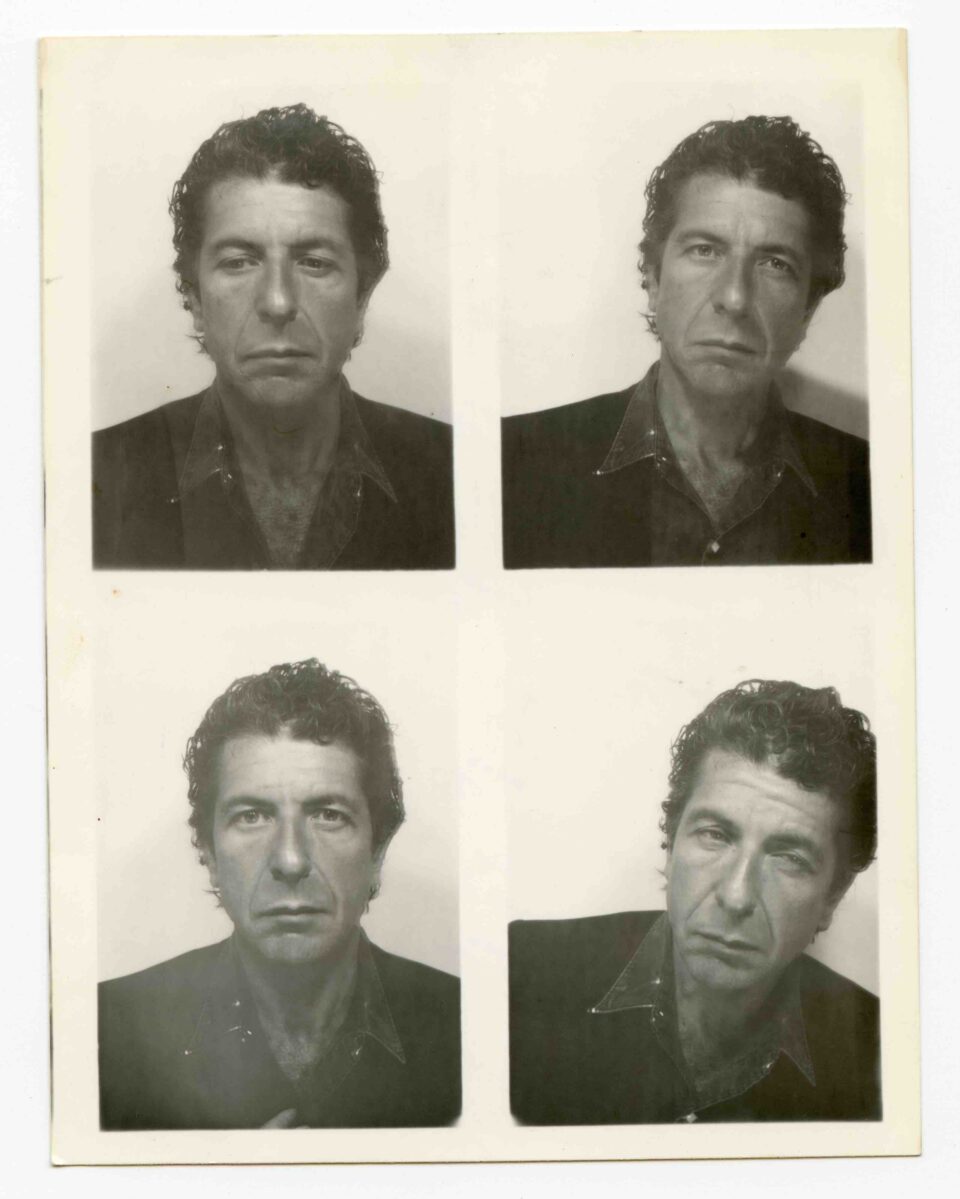

The NYC-based author Sloman—as famous for his travels with Dylan during the Rolling Thunder Revue as he is for being a literary device in songwriter/detective novelist Kinky Friedman's Manhattan mysteries—was onto Cohen’s case before 1974’s New Skin for the Old Ceremony and the interviews shared between them for that album. Their intimate, in-person conversations could and should be the basis for their own film, perhaps a My Dinner with Andre–like docu-dramedy. How the two got to that level stems from a simple assignment from Rolling Stone magazine and Jann Wenner, and the fascination never faltered. “I had just come back from graduate school in Wisconsin, to New York, and was writing features that were actually very cool—Lou Reed’s Berlin album, which nobody liked but me, and touring with George Harrison, who Jann wanted to trash,” says Sloman. “All this, and Leonard was a plum assignment.”

Larry “Ratso” Sloman

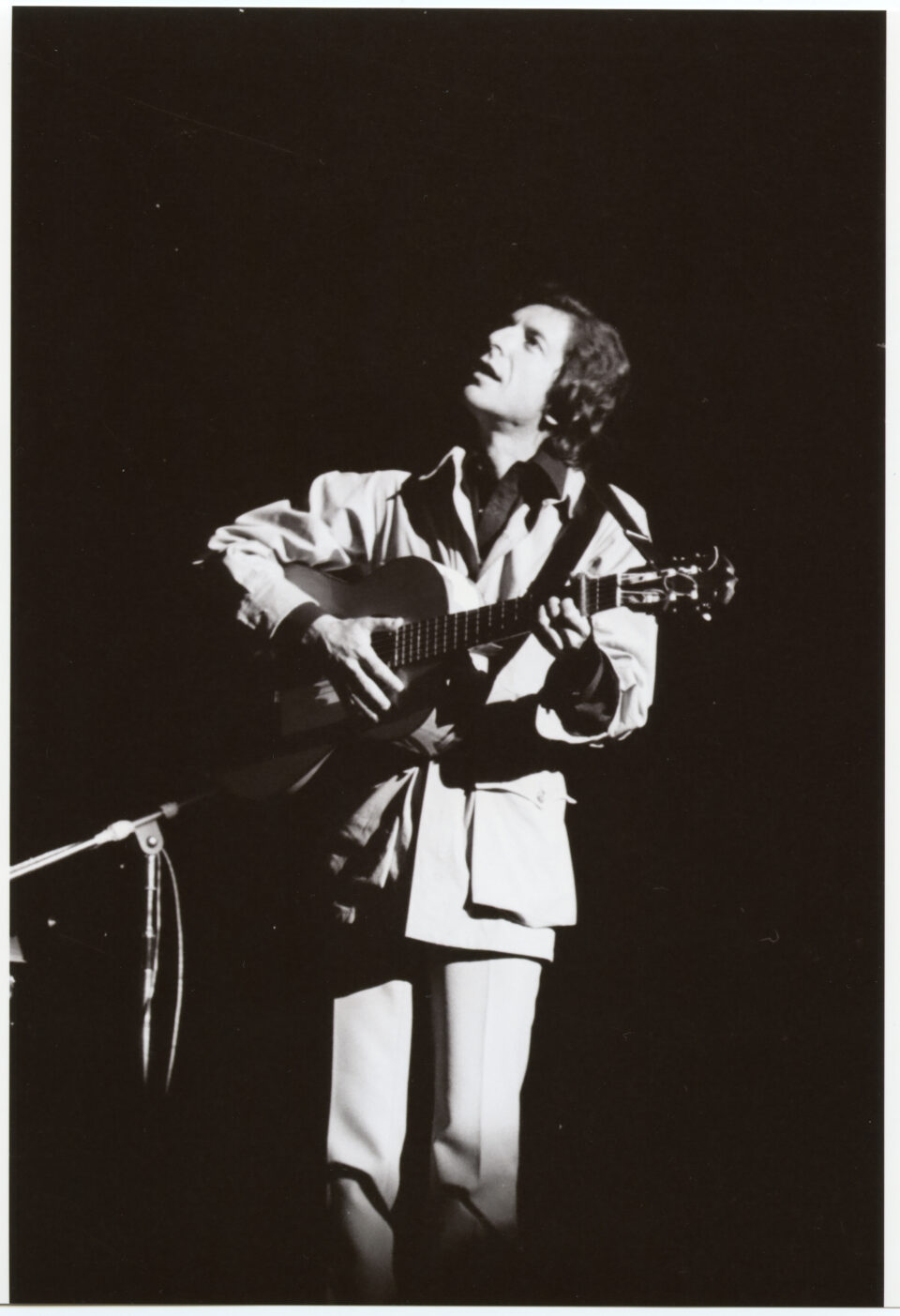

By 1974, at age 40 but with merely three albums behind him, the Canadian poet and burgeoning songwriter was a quiet mystery to most. “But we bonded immediately, because we were two Jewish workaholics,” says Sloman. “As you can see in the documentary, he had such attention to detail when it came to writing. It’s true that ‘Hallelujah’ took six years. I had that same obsession to my pieces.” From dressing rooms at NYC’s Bottom Line to stops at coffee shops to hotel rooms and more, Sloman and Cohen were tethered to each other’s words. “I remember him telling me something prescient as to his life and career after those Bottom Line shows: he wanted to play all night, he was so appreciative of the audience and their response. He grabbed a piece of cold chicken, opened up a bottle of wine, and said, ‘I want to do a lot of work, make songs that will stand for this moment, the age of 40, this season of winter.’ Remarking on the lines on his hands, the crumbling of his nails, Cohen said, ‘How many years do I have? If one’s health holds out, doing this forever would be marvelous.’”

“Every man should become an elder in his mind. And that’s what Leonard did: he became an elder to generations’ worth of music and lyric fans.”

— Larry Sloman

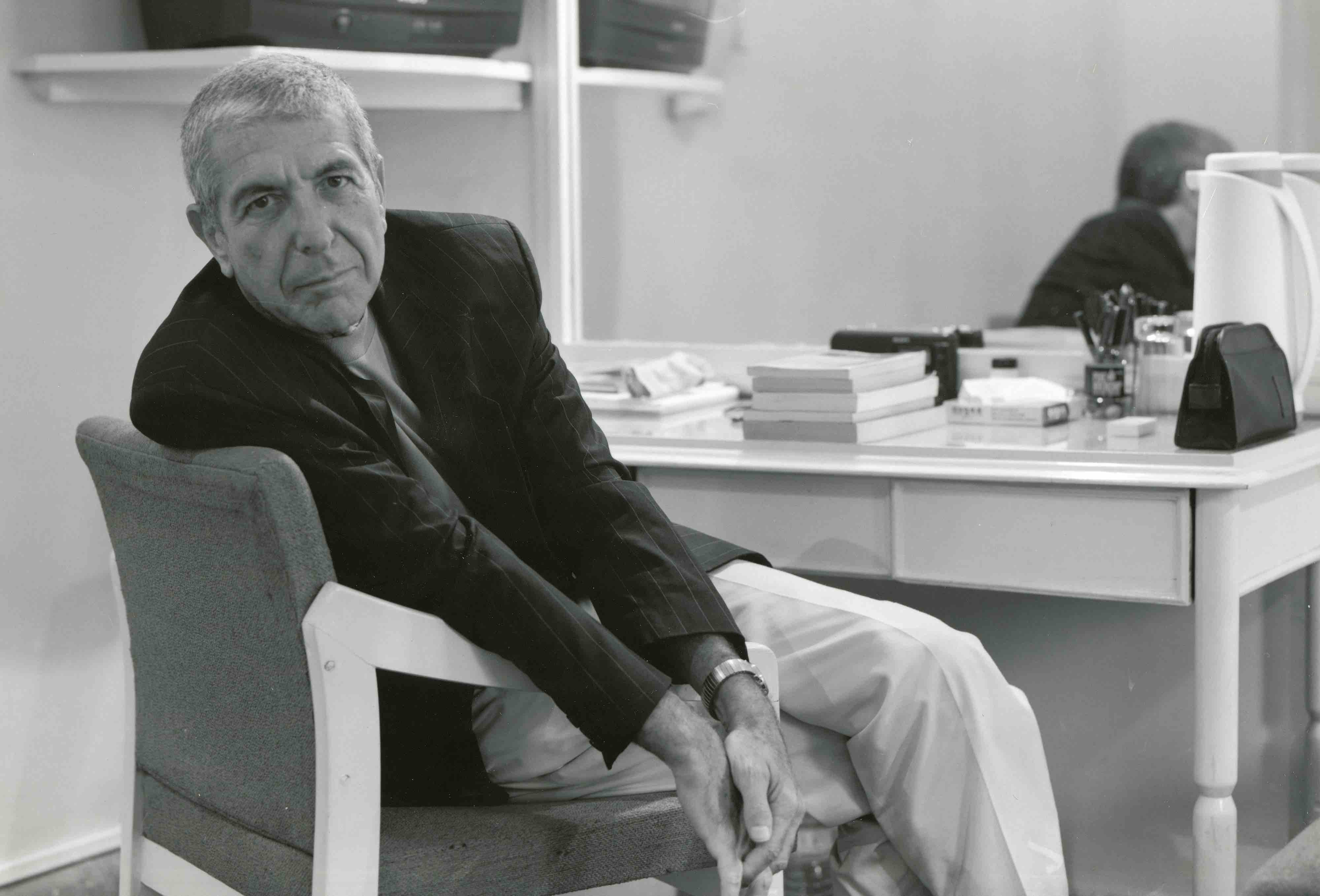

When you consider that he toured endlessly and more magnetically than ever between 2008 and 2013 (if at first only to refill the coffers when his then-manager stole everything he earned in a lifetime) and recorded brilliantly until the age of 82 and his death in 2016, Cohen’s words from 1974 rang true. The experience of maturity is what he strived to impart for the rest of his life. “Every man should become an elder in his mind,” says Sloman. “And that’s what Leonard did: he became an elder to generations’ worth of music and lyric fans. When he wrote, ‘I ache in the places where I used to play’ in ‘Tower of Song,’ by the time I was 60, I knew exactly what Leonard meant.”

Along with talking about the wonderful relationship between Cohen and Bob Dylan, their shared conversations about the writing process, and the times between the literary icons, Sloman seems to be a flashpoint where the song “Hallelujah” is concerned. He talked its virtues up to Dylan—the first person to cover “Hallelujah”—who played it twice on tour in Canada. Sloman talked it up to then-collaborator and Velvet Underground co-creator John Cale who recorded it for a 1991 I’m Your Man Cohen tribute compilation titled I’m Your Fan in a uniquely curated edit. Sloman was with Columbia’s A&R people when Jeff Buckley played a broken, angelic version of “Hallelujah” at Sin-é in New York City.

“I don’t know if Leonard was aware who did his songs—‘Hallelujah’ included—back then,” says Sloman. “I don’t know how much attention he paid to things like that. When Leonard said that thing in the movie that people should give [all the ‘Hallelujah’ covers] a rest, however, that was tongue-in-cheek. He was thrilled to get some sort of retribution for the song being ignored by his label in the first place.”

“I suppose he saw a kindred spirit in me. I got that feeling as soon as I met him. There was a warmth that I felt immediately, even though I was concentrating on remembering my parts.”

— Sharon Robinson

Cohen often told Sloman how tortuous the writing of “Hallelujah” had been, “sitting there in his underwear banging his head while he was working on its countless verses,” and “the betrayal of having it not be released.” In the end, after considering Cohen’s examinations of his devout Jewish roots and all levels of religion and spiritual seeking (“He once said to me that there is no afterlife, that the world is a butcher shop”), Sloman says it’s that level of sacred and secular self-examination that helps build the power of the song.

Vocalist and composer Sharon Robinson started her affiliation with Cohen as his back-up singer for tours in 1979 and 1980, then again during that long run between 2008 and 2013. Additionally, Robinson and Cohen collaborated on writing songs such as “Everybody Knows” and “Waiting for the Miracle,” and working together on his 2001 album Ten New Songs and 2004’s Dear Heather. If anyone has a truly unique portrait of Leonard Cohen, it’s Robinson. “Jennifer Warnes auditioned me to sing back up with her on the I’m Your Man tour for Leonard, and I suppose he saw a kindred spirit in me,” says Robinson regarding how their professional relationship continued. “I got that feeling as soon as I met him. There was a warmth that I felt immediately, even though I was concentrating on remembering my parts.”

Going on to become good friends in her estimation, the chemistry between Cohen and Robinson manifested itself in various ways, including writing songs based on life experiences and spiritual paths. “Like Leonard, I’ve always been something of a seeker, with many religions leading to the same place,” says Robinson. “Philosophically, we were much alike.” And musically, with her own studio and the ability to write melodies, craft rhythms, and provide vocal counterpoints, Robinson was a “one-stop-hop” when it came to collaborating on Ten New Songs and Dear Heather. “Leonard became comfortable with certain people in his life and liked to stick with them,” recalls Robinson. “He wrote many poems when he was away for five years, in retreat on Mount Baldy, and I took those words home, developed melodies, and we went from there. I knew the person I was writing for, and knew what he needed.”

Romantic or not, Robinson muses in the new documentary that Cohen placed women on a pedestal. How Robinson benefitted from such a high stature came down to respect for women’s “spiritual place, far beyond men.” What Cohen also held in high regard, where Robinson was concerned, was that she had a deep musical education—something schooled that Cohen lacked, and a crucial element of her relationship with “Hallelujah.” “When Leonard ran it by me, ‘The fourth, the fifth / The minor fall, the major lift,’ he wanted to make sure that it made sense to a schooled musician,” Robinson says. “It was a brief discussion, but he had to know that it was right. From there, the song evolves, has a life of its own, and grows into something with many sides. Singing that song every night as we did for five years straight, I’m still finding new meaning in the words of ‘Hallelujah.’” FL