Rap has given a lot of young Black men a foot in the door of the booming legal cannabis industry, usually in the form of lucrative endorsements and vanity brands. Yet getting into legal weed was a more personal project with a broader vision for Vic Mensa, who, like a lot of Chicago rappers, has inherited a drive for community service and economic self-sufficiency passed down from the city’s time as a center of the Black Panther movement.

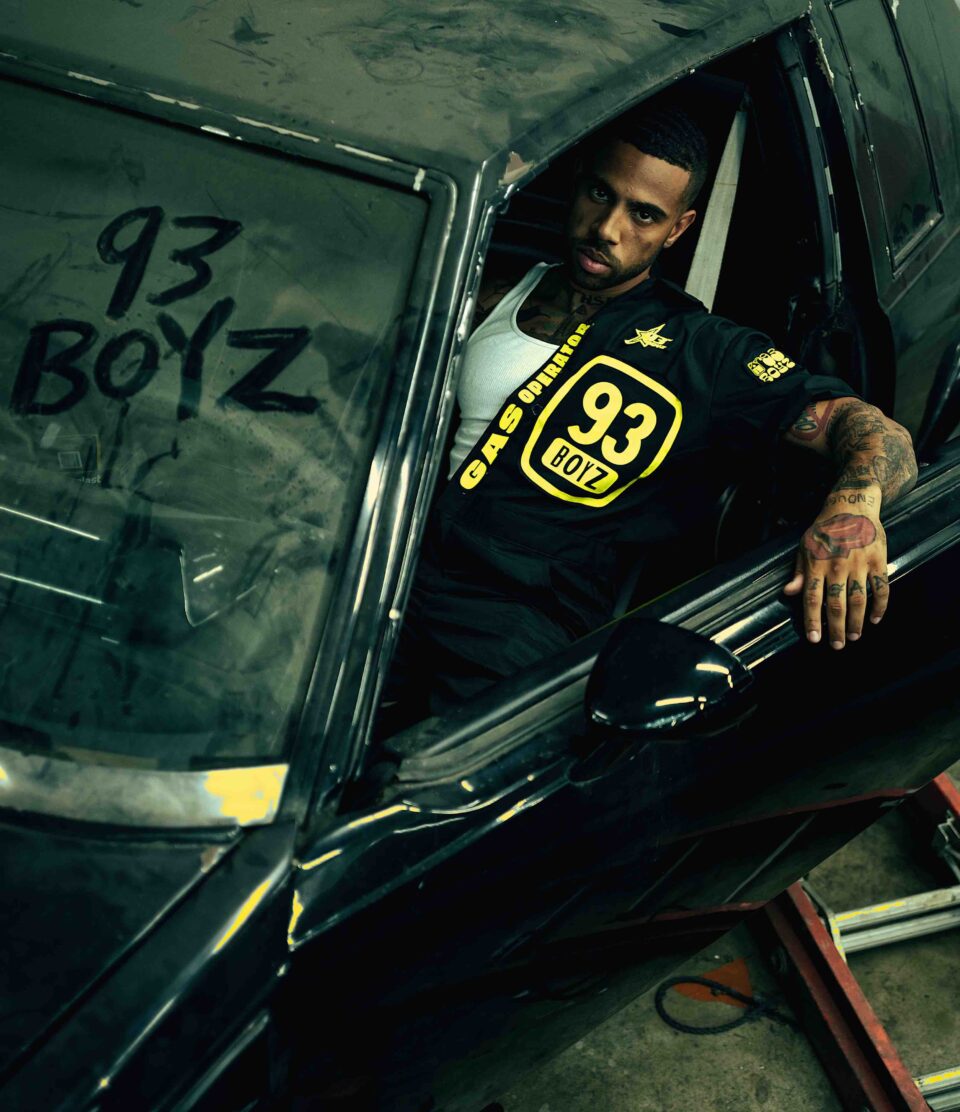

This week he launched 93 Boyz, a brand that combines cannabis connoisseurship with a social conscience. On top of promising “the heaviest, headiest gas available anywhere,” the brand is a collaboration with Mensa’s SaveMoneySaveLife nonprofit, and they’re putting a portion of its profits into prison reform and equity in the cannabis industry. Ahead of the launch, we got Vic on the phone to talk about his foray into the legal weed game, how he’s giving back, and where he’s going next.

Tell me a little bit about what’s going on with the brand.

93 Boyz is the first Black-owned cannabis brand in Illinois. That is at once extremely exciting and also deeply troubling, because the truth is that the criminalization of plant medicine has been used to ravage the Black community, and the fact that there’s little to no representation of that community in this highly lucrative industry is a real issue. So I’m excited to be addressing that, while also in complete recognition that our exceptional ability to be involved does not change the fact that our community’s still being excluded. 93 Boyz is built upon the ethos of giving back to the community that we come from. We’re going to be using a portion of all of our proceeds for different initiatives for the people.

“The entire process for legalization has been really rife with corruption and deception. There’s still no Black ownership in the industry.”

We’re kicking it off with a program I’m calling Books Before Bars, where we’re sending a bunch of books into Illinois jails and prisons. That’s an idea that really just sprang out of my own experience, seeing the way that sending a person a book can free them mentally, even while their body’s still in chains. And I’ve seen these radical transformations take place, sometimes from tiny, 200-page books—just seeing the way that a person has found real freedom amidst a soul-crushing circumstance. I just want to shout out the people who’ve already been doing this work. We’re collaborating with a Black-owned bookstore in Chicago called Semicolon Bookstore. And also shout out to my friend Noname, who’s been sending books into prisons as well, and everybody across the nation that’s been doing that.

I heard a little bit about how decrim was rolled out in Chicago, and it seems very biased toward white business people, and not aimed at the Black community.

The entire process for legalization has been really rife with corruption and deception. There’s still no Black ownership in the industry. There’s a social equity program to get the communities that have been most impacted by the war on drugs involved in the industry…it’s really just been social equity in name. In practice, it’s been smoke and mirrors, a big finesse, and a lot of the same people continuing to rake in all the dough. There’s been a couple of very deserving people from the advocacy side of things, such as a woman named Edie Moore and her Chicago NORML organization, who have gotten that necessary foot in the door, but overall it’s left much to be desired. It’s really corrupt. It’s Chicago. At the end of the day, America is as we know it to be, you know?

It seems like even in other cities where there’s been such a vocal push to make things more equitable and give reparations to the communities that were most impacted by the drug war, it just never pans out.

Because within the framework of that headline and that idea, the powers that be are always gonna find the ways to line their pockets. But there are a lot of brilliant people in Chicago who are committed to this shit, and have far from given up. There’s an organization called EAT that’s run by a friend of mine named Rich Wallace. He was in a hip-hop group called BBU who were fucking sick. He’s doing some really great cannabis advocacy work, and his whole angle right now is to push for the tax money generated from cannabis to be used as actual reparations. Rich is ill because he’s talking about actual cash payments to members of disenfranchised communities, and he’s got research and a history of actually trying this shit out and seeing how impactful and valuable it is.

“I’ve been involved in the cannabis industry in a non-legal capacity since age 11. Before I ever sold a rap, I sold an ounce.”

The last time we talked you were saying something about wanting to start a dispensary. Was that part of the plan, or is this a different direction entirely?

93 Boyz was really born of a different inroad. From the jump, when the cannabis industry opened up for recreational use, my friends and I have just been focused on how we enter it because, you know, I grew up with this. I’ve been involved in the cannabis industry in a non-legal capacity since age 11. Before I ever sold a rap, I sold an ounce. And not only that, but historically, the reasons why cannabis has been criminalized are so intrinsically linked to the Black community, and Black musicians in particular. Learning that cannabis’s association with jazz musicians was one of the most influential factors in its criminalization, it just lets you know that there’s a real need here.

So we just came up with this concept and kind of started building it in the streets. My partner in it is one of my guys who’s really just put his hands in the dirt and came up with gold and learned to grow. We connected with a cultivator called Aerīz that does an aeroponic process for their grow. It’s like the most economically conscious cannabis company in the market. One thing I really want to do through 93 Boyz is to build the first indoor skatepark for the kids in Chicago. Growing up skateboarding, we were really limited by the winter. You can’t skate that way, and there’s no indoor skate parks in the city.

So it seems like 93 Boyz is kind of like a channel for you to start doing more community-based stuff and make some projects happen.

100 percent. As far as cannabis is concerned, but also the community projects, I’ve just been kind of immersing myself and studying the art of branding, because an artist today has to be a brand, you know?

Are you resentful at all that for a lot of artists, it’s like, “Why do I have to do this, too? Isn’t it good enough that I’m a good musician, that I’m a good artist, that I’m creating good art?”

The place I am in my life is one of shedding resentment in totality, you know? And I’ve just come to really understand and recognize that the harboring of emotions and sentiments such as resentment and regret are actively working against the manifestation of success and joy and gratitude. I used to feel really resentful of the fact that I had to be on social media and do all this stuff to be an artist, because in all honesty, it’s not my passion. But I’m just cultivating gratitude, focusing on gratitude. I did a show the other day in Brooklyn, and since then, I’ve often gone back to it and thought, like, “Man, if I wanted to, I could be fucking resentful that that show was in Prospect Park and not Madison Square Garden.” But I could also choose, as I have chosen, to be grateful for each and every person at that concert.

“I’ve just come to really understand and recognize that the harboring of emotions and sentiments such as resentment and regret are actively working against the manifestation of success and joy and gratitude.”

Gratitude is so powerful. It will transform you.

It’s everything. I think the age of social media has programmed so many of our minds to exacerbate the “compare and despair,” as my friend would call it. The transformation that I’ve felt in my life from really starting to lean into gratitude has been immense. I’m someone with a lifelong history of mental health concerns, taking maybe 10 to 15 different medicines up until I stopped in January. And what I found to be the most impactful to the betterment of my mental health hasn’t been medication or anything like that. It’s been meditation, and constant vigilance of my thoughts. I’m just grateful that Miles cares enough about what I got going on to sit and listen to me talk about it.

Before we go, I’m curious what else you’ve got in the works right now.

I just finished my album. So this will be my second official full-length, and that’s what I’m most focused on right now. I just got back from Ghana. While I was there, I was shooting a lot of things for an accompanying short film for the album. We shot some brilliant, beautiful shit, like traditional African religious ritual ceremonies. Also, we took a group of eight high school kids from Chicago out there with us. Along with some of my guys, and an organization in Chicago called The Academy Group, we were able to organize this life-changing experiential learning journey for these 17- and 18-year-olds, for these Black kids to touch the continent for the first time in their lives.

Chance and I are working on organizing a festival in Ghana with the intention of just bridging the gap between the diaspora and the continent. And in recognition of the fact that as Black artists, we perform Europe 10 times over, Australia, Asia, South America, all before ever stepping on a stage—or even on soil—on the continent of our origin. So we’re working to change that. It was a lot of work when I was out there. I was filming, so I was trying to catch the sunrise every morning at fucking 5 a.m. I learned a lot about sunrise on this trip, because there are moments when the sky is a certain color, and it’s only that color for five minutes. Yo, I didn’t sleep for shit. But you know, I’ll sleep later on. FL