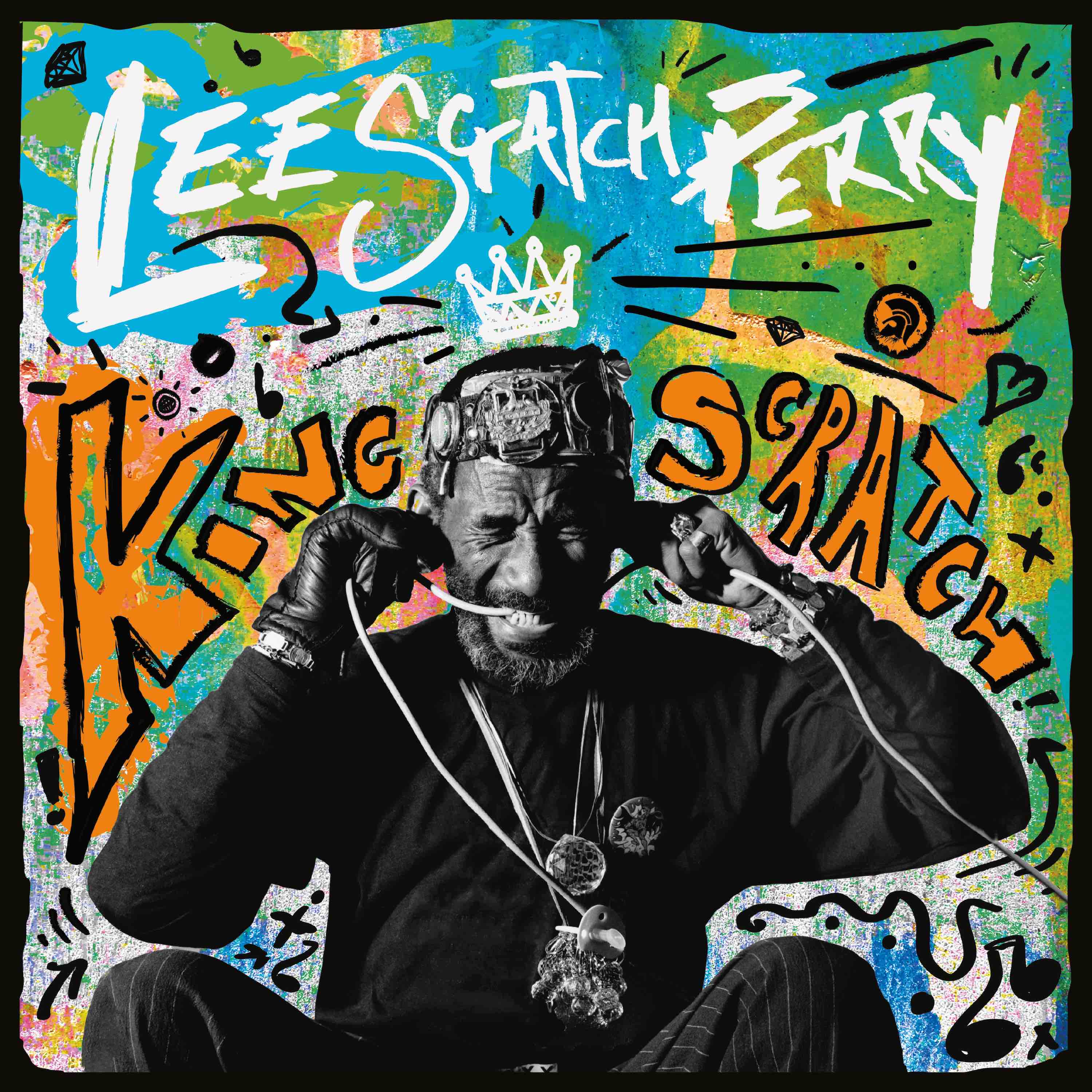

Lee “Scratch” Perry

King Scratch (Musical Masterpieces from the Upsetter Ark-ive)

TROJAN

To craft a four-LP, four-CD, 109-song collection from the unwieldy, amorphous career of dub maestro/punky reggae party starter Lee “Scratch” Perry is like carving into a cumulus cloud and finding the sun. Where to start? What to focus on? From 1968’s early sampling example “People Funny Boy” through to his continued silken and stony music making until passing into space in 2021, the Saturn-bound producer and toaster made weirdly spiritual, bass-bin-rattling, ganja-referenced sounds the likes of which could’ve made Sun Ra green with envy while inspiring everyone from Bob Marley to the Beastie Boys.

With King Scratch, the story of Perry—his Ark-istry, his relationship to every important reggae music maker from Coxsone Dodd to Adrian Sherwood, his love of weed and God, and the bad juju that caused him to burn down his own studio in Jamaica—is historic and stuffed into a handsomely illustrated, tenderly penned book-in-the-box from biographer David Katz and photographer Adrian Boot.

Still, it’s Perry’s peerless track record that tells the best, scariest, and silliest stories—everything from the rubbery skanking ska of his 7-inch mix of “Jungle Lion” and the menacing classic “Return of Django” (both by Lee & the Upsetters), to the rub-a-dub space funk of latter-day solo cuts such as “I Am a Madman” and “Jamaican E.T.,” to Scratch’s work for loping, politicized reggae vocalist Junior Murvin’s “Police and Thieves” (in a previously unreleased mix) and the sweetly, sonorous “Hurt So Good” by Susan Cadogan.

Perry’s round, rubbery productions are raw, sumptuous creations—the harsh yet soulful likes of “Beat Down Babylon” from Junior Byles, the charmingly clunky “Three Blind Mice” by Max Romeo, the warmly homespun “Back Weh” by Faye Bennett—with each take capturing Perry’s sense of roomy ambience, passion, and menace in one bass drop. The two studio-centric CDs of Black Ark Adventures from 1974 to 1976, then 1976 to 1977 (13 cutting tracks from one 12-month period alone), are worth the price of the entire box just to have in one place. Though long familiar with his charges’ tracks, listening again to how Perry finessed his artists to fit into his spacious, loopy vibe makes me want to pull out every individual artist’s album and dig in.

Yet it’s the Perry tracks, with his Upsetters ensemble early on or his pure and prickly solo work, that stand out on King Scratch. From the mumbling young buck to the screaming lion in winter, from the aptly titled “Bucky Skank” and “Stay Dread” to the deeply grooving premonitions of “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and “I’ll Take You There,” this box is the best reggae history lesson you could own.