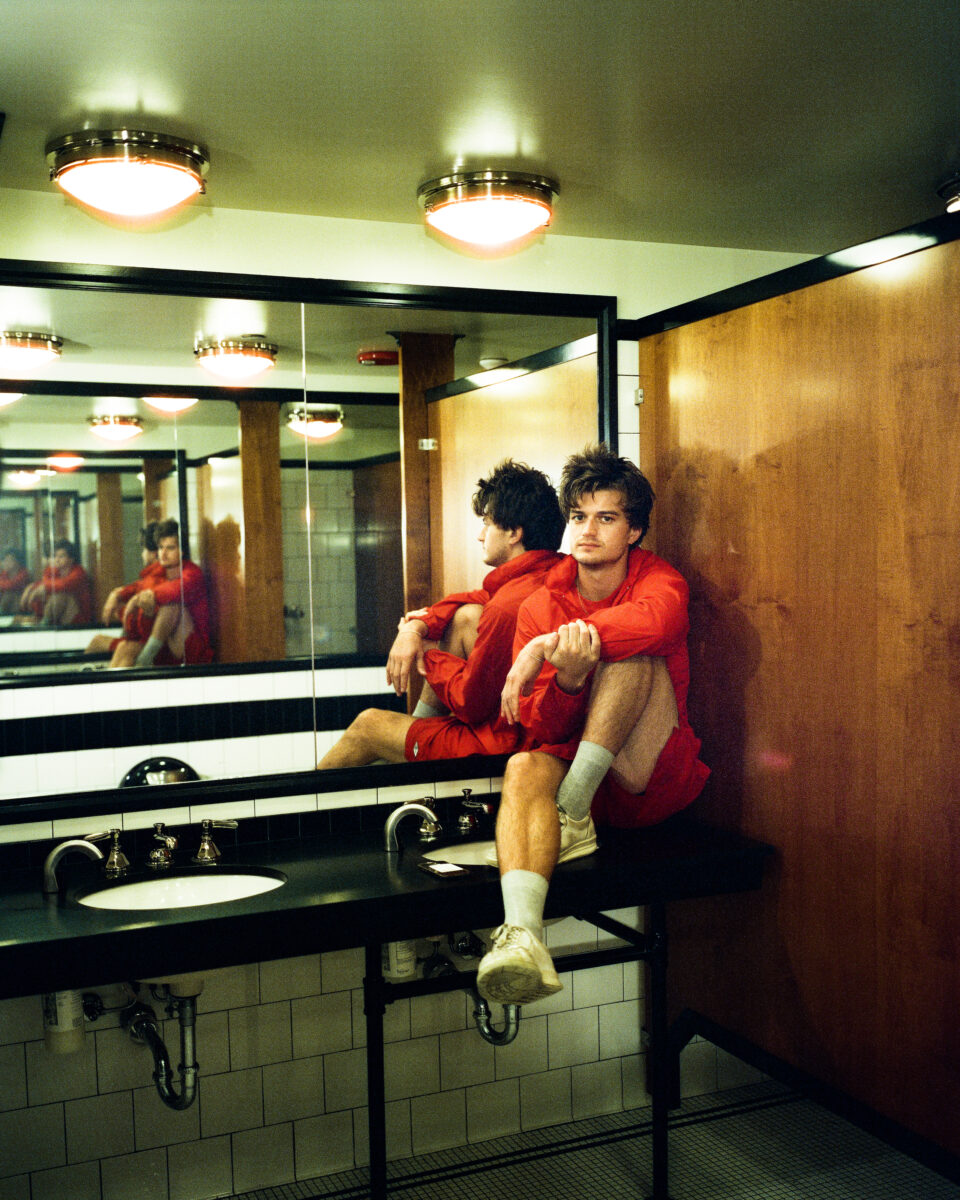

Joe Keery wants to go back to a certain golden age of music. No phones or collabs over Zoom—just himself, studio musicians, and producers wizarding over a massive stripboard, confined to a studio for a few weeks with the challenge of throwing ideas to the wall and seeing what sticks. “It would be nice to see how a different environment affects the music you’re making,” he tells me over Zoom of his dream studio locale: Paris. He sits in front of a royal blue velvet couch as he envisions how he wants to challenge himself with making music in the future.

He invokes a romanticized pressure cooker situation where one is forced to follow their creative intuition in a single studio for a short number of weeks. “Constraints are not necessarily bad,” he says. “Having some outside pressures can be good creatively, because you’re forced to make decisions.” A second passes before a soft smile begins to take shape across his face: A cheesy full-circle moment is about to take place, and he realizes this before the words fly out of my mouth. “You’re forced to decide,” I say, smirking at the namedrop of the album he’s promoting for this interview. “Deciiiiiide,” he says in a sing-songy voice before flailing his arms around in a circle.

Calling in from Rome, I catch Keery right before he’s about to go back on set for a new movie he’s working on, acting alongside Willem Dafoe and Lily James. Keery is most known for his acting career, starring in Stranger Things as Steve Harrington and showing his range with comedies like 2021’s Free Guy and thriller-horror films like 2020’s Spree. Although acting has brought him stardom, dethroning Robert Pattinson as Hollywood’s new hair king isn’t his only creative pursuit.

Before Joe Keery was a household name, he gained familiarity in the Chicago music scene playing in the meditative psych-rock group Post Animal. In 2019, it was officially revealed that Keery had parted ways with the band due to scheduling conflicts and the rise of his acting career. Later that year, he released his first single “Roddy” under the name Djo. His growing fame seems to have nurtured his creative output. That same year, he released his debut album Twenty Twenty.

“The imagery of the eight-ball [on the album cover] is asking the universe, ‘What should I do?’ The universe’s answer is just, ‘Decide, dude. Decide.’”

Now, three years later, Djo returns with the sophomore follow-up DECIDE, which demonstrates an exciting progression from mystical psych-rock to punchy ’70s synth-rock. Inspired by Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories, Keery uses that robotic sound to explore existential dread and technological mundanity. “That’s a band that as a really young kid I found and thought, ‘This is insane,’” he says of the French duo, his eyes growing wide. “I didn’t really understand it because my context for bands was Bruce Springsteen and Led Zeppelin. It’s a band you can kind of keep going back to, and the older you get, you glean something different from their music.”

On Twenty Twenty standout “Chateau (Feel Alright),” Keery gets lost in a dreamy, uncertain certainty. “It’s a decision that I’m glad that I made / I’m still uncertain that it happened at all,” he sings alongside a noodling guitar. His voice has a slight echo, which emphasizes his mind’s instability. It’s easy to imagine Keery lost in his memories, adding and subtracting details in a calm daze. Later, on “Mortal Projections,” Keery eerily declares: “I’ve seen reflections of my mortal self projected on the wall.” It wouldn’t have been necessarily accurate to say that nostalgia, the passage of time, and indecision have been themes throughout Keery’s music, but DECIDE makes clear that these concepts are routinely bumbling around his head. At times, Twenty Twenty crept along with an unsettling inconclusiveness; on DECIDE, Keery pushes forward with urgency and resolve.

“I’m an indecisive person,” he says. “A lot of change is based around making decisions. That’s a quality that I appreciate in other people and wish that I could [have].” He looks off to the side and smiles before referring to his album’s cover. “The imagery of the eight-ball is asking the universe, ‘What should I do?’ The universe’s answer is just, ‘Decide, dude. Decide,’” he laughs. “You can take out the ‘dude,’ though. I don’t think it’s ‘Decide, dude.’” But who’s to say what the universe sounds like. Maybe, it can take the form of some hippie surfer bro ushering us toward solutions.

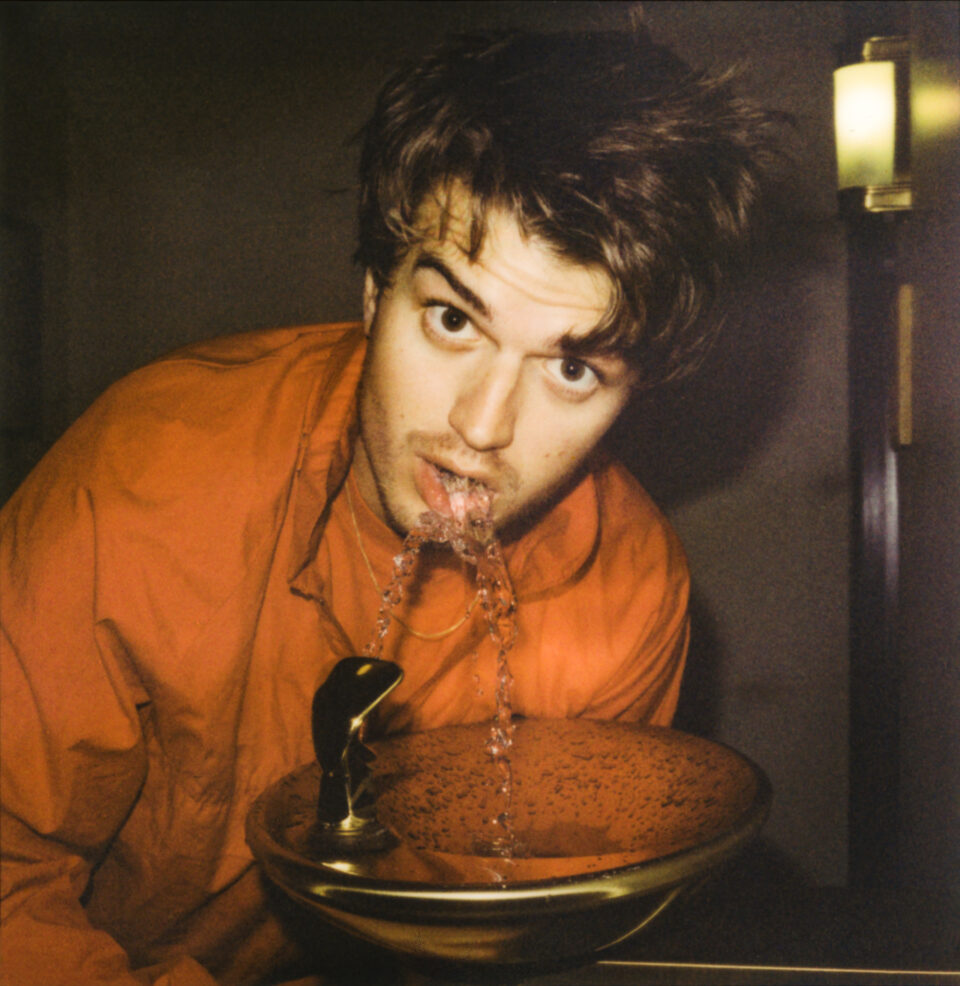

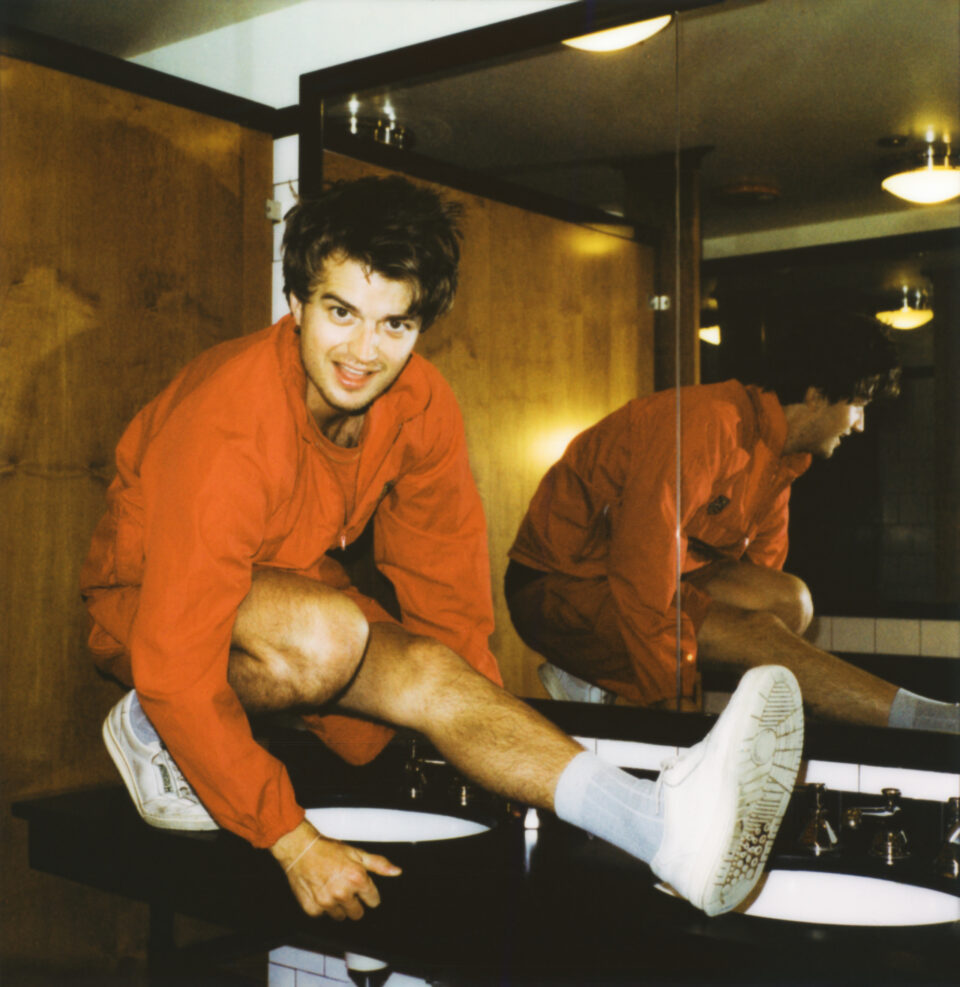

It’s this combination of lightness and existentialism that makes DECIDE worth its runtime. Whether it’s recognizing a shitty friendship, confronting new adulthood, or ignoring the cringey urge to stalk yourself on the internet, Keery doesn’t take himself too seriously, yet doesn’t hold back personal faults and fears. On “Gloom” he sounds like he’s imploding a bit. He bashes someone’s mom and girlfriend, then later frets about not being able to walk his dog. And it’s funny—it’s often hard to tell if Keery is battling a frenemy or himself: “Your insults don’t affect me with my favorite coat on / I know my hair looked good in the bathroom at the bar / Turns out I left my wallet at the bathroom bar,” he sings over a lovechild beat of Devo and Gary Numan.

Keery reveals his innate ability for comedy no matter what he’s making. “It’s difficult to not do it, to be honest with you,” he says while discussing the humor in “Gloom.” “It’s difficult sometimes not to have humor in songs. That was a song that poured right out. I guess it’s a part of my personality. Life is crazy, and a lot of the time things don’t make sense.” Comedy is part of his art, but not something he wants to make the central point. “For a long time, I was like, ‘I don’t want to make a comedy album.’ So maybe I shied away. But this last time I felt more comfortable in letting what will be, be. The second you censor yourself you start to subtract the thing that makes it unique to you.”

He looks to icons like John Lennon and Paul McCartney when staying true to himself throughout the writing process. “The majority of the time, I’m not like, ‘Ooh, these are nice lyrics,’ then applying those to the song. Something I love about Lennon is that a lot of his lyrics seem very stream of consciousness. It poured out of him in a way, but it means something as well. I’m not the type of guy who’s writing a lyric like a poem then applying it to music that’s already been written. A lot of it’s based around being inspired by the music, listening to it, and laying something on top of that.”

“I felt more comfortable in letting what will be, be. The second you censor yourself you start to subtract the thing that makes it unique to you.”

The humor in Keery’s songs acts mostly to cope or find relief from life’s stresses. “I was mostly trying to be open and true to myself when writing the music. At the end of the process, you kind of have to find the throughline as to what the songs are about.” At 30 years old, that throughline is presented as Keery making sense of his late twenties. “I think universally, it feels you’re at the crest of this wave facing this big sort of abyss before you. You start to question what you really want out of your life, I guess. What is important to you? What do you value? [This album] is the only place where I can talk about those sorts of things creatively. From 25 to 30, I’ve seen the most change with myself. I’m inspired by it and also terrified by it.”

He details what terrifies him most about these changes: “Things not being the way they were. Saying goodbye to things is difficult. Saying goodbye to chapters of your life that you’ll never get to revisit is a sad realization, but a part of life. Not wanting to say goodbyes is a big theme in the record.”

DECIDE came together with the help of what Keery calls a “supergroup of friends” which included Adam Thein, who also worked on Twenty Twenty. The two met as a result of Keery fawning over Thein’s old group Dolores. Keery reached out to Thein after he’d moved to Oregon and the two have gone from collaborators to close friends. Other collaborators include his friend Sam Jordan, who Keery grew up playing with, Slow Pulp drummer Teddy Matthews, and Kainalu’s Trent Prall. His face brightens describing what made him hunger for a small hint of those golden days—four dudes in a room, jamming. “Get Back was coming out as we were recording. We’d get up in the morning, we’d make coffee, watch some of the documentary, and then we’d probably go in around noon and stay ’til midnight, and then come home and talk about what we did and do that for 10 days. It was incredible.”

One of DECIDE’s strongest tracks was born from that period, which comes the closest to what Keery idealizes as the “old way of making music.” It also, ironically, showcases Keery waving goodbye to the past. “And when I’m back in Chicago I feel it / Another version of me, I was in it,” goes the melancholic synth ballad “End of Beginning.” Here, Keery looks back on a younger version of himself in the city he came of age in. He captures the phantom-limb sensation that comes back when you revisit a former home; memories of yourself begin to feel bittersweet, and that past version almost becomes a familiar stranger with a blurred face. “That [song] felt like an introduction to a new way of being creative and making music that I kind of want to continue to pursue.”

“Saying goodbye to chapters of your life that you’ll never get to revisit is a sad realization, but a part of life. Not wanting to say goodbyes is a big theme in the record.”

As a self-proclaimed indecisive, Keery reveals his go-to strategy for battling uncertainty. “My favorite part of the process is being like, ‘Let’s do the opposite of what we think is right in this situation, see if it works. Maybe it won’t, but at least we tried it.’ And so I’d say more often than not some really exciting things come out of that.” He uses this open-ended strategy for his acting as well. There’s recognition that decisiveness isn’t necessarily a perfect trait. In some ways it might lead to stubbornness. “When I started this [album], I had a bunch of different ideas about what I thought it would be, or what it would turn into. It’s completely different. So I think you can plan and you can plan, but at the end of the day, the music is going to be kind of what it is.” He adds that it’s best “being open to change, and realizing that if you try something, it doesn’t mean you’re stuck doing it that way.”

What Keery is getting at, both on his new album and in our conversation, is that revisiting any idealized golden age has its merits—but taking the risks that come up along the way and seeing where you end up may be the only way forward. FL