It felt like journalist Lizzy Goodman was looking out for us millennials back in 2017 when she published her long-gestating oral history of the early-aughts NYC garage-rock revival a few years ahead of the 2022 reality of regularly waking up to find music sites publishing 20-year anniversary articles about our favorite albums from our formative years. Reading Meet Me in the Bathroom cushioned the bizarre existential blow that comes with realizing that The Strokes’ Is This It, Interpol’s Turn on the Bright Lights, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Fever to Tell are all college-aged, with Goodman’s reporting extensively documenting the scene for the first time in a way that felt less like gossipy blog content (well, OK, it’s pretty gossipy) and more like the type of rock and roll history etched into the genre’s canon by documentaries like The Decline of Western Civilization and other films about now-iconic scenes built from the ground up.

And if that canonization still doesn’t feel guaranteed five years later, filmmakers Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern (who previously brought us Shut Up and Play the Hits, the concert film of LCD Soundsystem’s first-ever final show) are ensuring we treat it as such with their new documentary adaptation of Goodman’s account, which takes that fly-on-the-wall reporting and embellishes it with raw footage of the scene mixed with montages that explicitly slot these bands into the same rich cultural tapestry that includes artists like Andy Warhol and The Velvet Underground.

“For sure I see that,” Goodman tells me, agreeing with the filmmakers that Julian Casablancas and Karen O comfortably fit into the lineage of rock figures such as Lou Reed and Patti Smith. “This is the story of New York, it’s the story of American identity, and it’s deeply the story of punk rock in the city in the ’70s. When I arrived it was like, ‘I don’t know if this will ever happen again, but if it does I want to be there for it.”

“This is the story of New York, it’s the story of American identity, and it’s deeply the story of punk rock in the city in the ’70s. When I arrived it was like, ‘I don’t know if this will ever happen again, but if it does I want to be there for it.”

The book, Goodman adds, was intended to “put bookends on that period of time” (which, per its subhed, spans from 2001 to 2011) rather than present it as distant history, though the film is at least superficially a historical account of the changes New York underwent over the course of the early ’00s as technology and politics (more specifically: 9/11 and dramatic changes within the music industry ushered in by file-sharing sites) rapidly reshaped the cultural landscape.

Yet Goodman and the filmmakers seem to agree that the subject they’re capturing is entirely unmoored from its place in time—even beyond the familiar sonic and stylistic motifs alluding to past decades. “I don’t think of it as, ‘Oh, the sounds of New York City during this particular time were especially revisionist,’” Goodman says. “I think of it as, ‘This is just our version of that thing that’s the nature of music and culture, which is to pull on a thread that goes throughout culture and history.’”

Much like the simultaneous punk movements carried out across the globe in the 1970s, the one Goodman’s covered was a necessary response to what felt like a cultural dead-end at the time. “If punk is born out of a need for punk, our scene was also born out of a need for punk, because nu metal fucking sucked and everyone wanted to kill themselves,” she elaborates. “Our scene was a reaction to feeling like the 20th century was ticking into the 21st century, and all we had as young people as a stand-in for that rebellion and sexuality was fucking Fred Durst, Mark McGrath, some spiky, gel-haired pretty boy from the TLR world—it felt really offensive.”

“Our scene was a reaction to feeling like the 20th century was ticking into the 21st century, and all we had as young people as a stand-in for that rebellion and sexuality was fucking Fred Durst.”

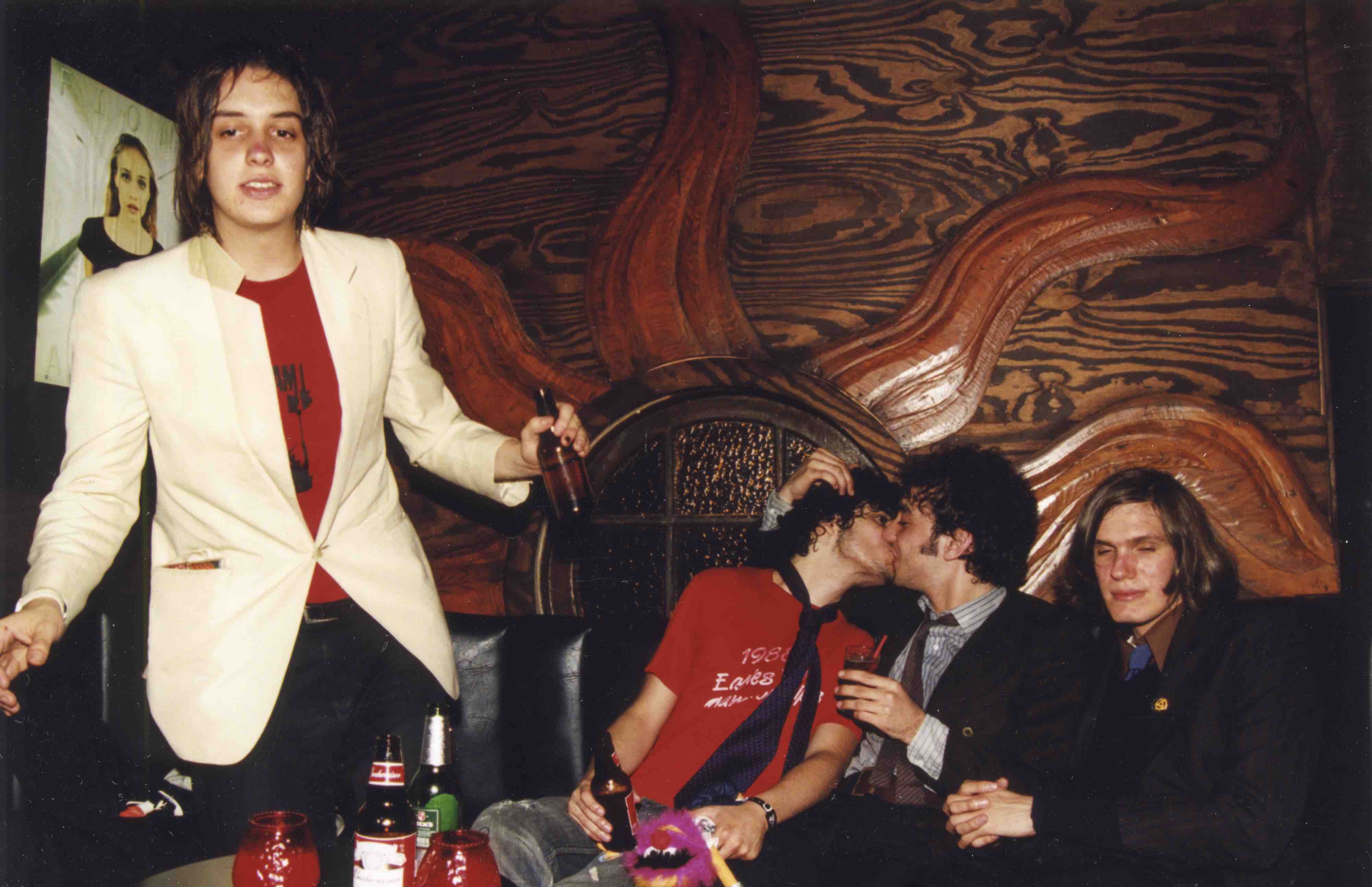

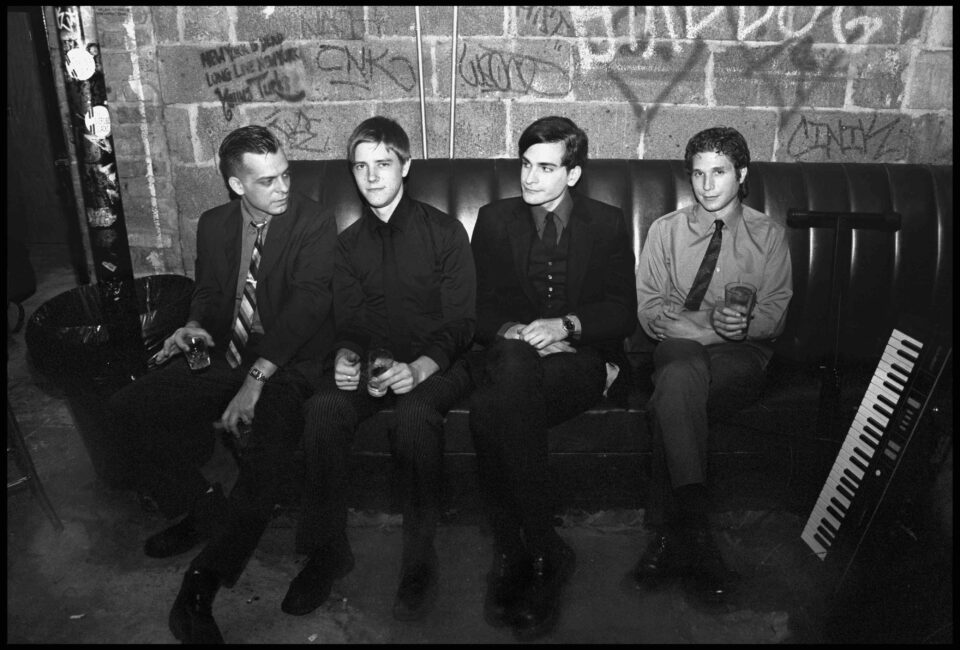

While the bands documented in Meet Me in the Bathroom strayed significantly from this mainstream image, the book and film both implicitly shed light on how manufactured their personas felt when mediated through press photos, TV performances, and other public appearances before social media offered a 24/7 glimpse into their everyday lives. As Goodman’s interviews demonstrated, Interpol’s Paul Banks will be the first to admit that his band’s impossibly suave Bright Lights–era photoshoots and mysterious music videos were far from representative of the youthful ignorance that plagued the band early on, while the documentary presents us with images of the young Strokes’ erratic public behavior that suggests they were just another gaggle of immature twentysomethings inspiring subway passengers to relocate to the next car at the next stop.

“It’s not so much that I wanted to pull the wool back from people’s eyes and let them see that, like, Paul is kind of a bro or something,” Goodman laughs, thinking about the unrealistic personalities myself and others always projected onto these bands. “It was a goal of mine to make the story not about the music, and not about these rock stars being fucking fancy rock stars, but about the human beings with all their insecurities and vulnerabilities and giant egos and moments of doubt who created this music that so many people love.”

She reminds me that the project was intended to be a timeless and archetypal coming of age story just as much as it was a historical account of a scene that’s just now starting to enter the annals of rock history. “Really it’s also for someone who says, ‘I hate these bands, I never wanted to hear about them, but I found this story really compelling because it’s about human beings.’”

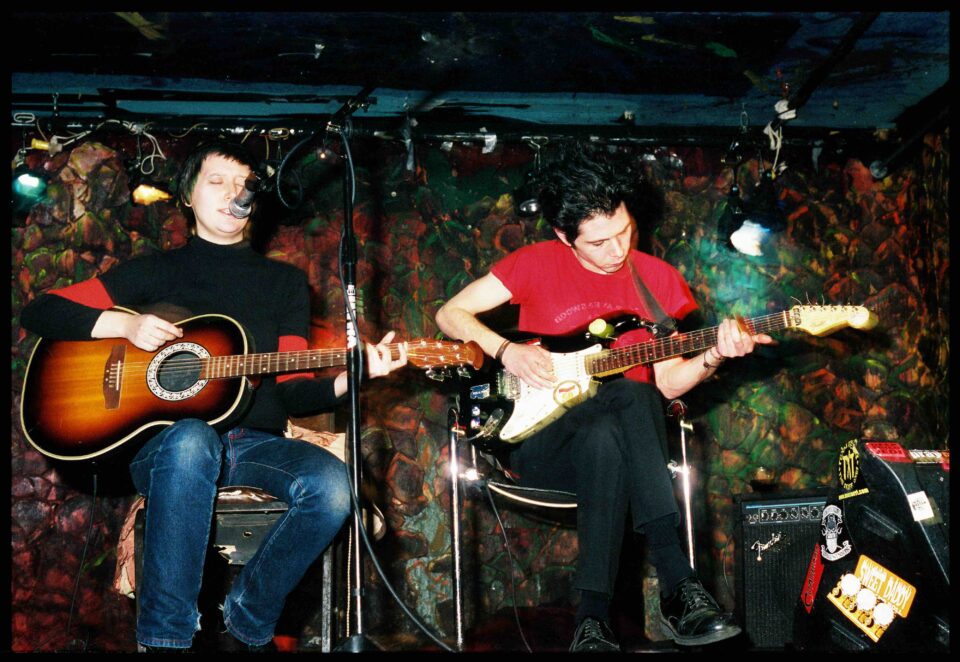

With the film condensing over 600 pages of often-conflicting testimonies (“It’s all Rashomon,” Goodman’s said in interviews) to under two hours, it’s Karen O’s storyline that gets the most screen time—which both illuminates one of the book’s most interesting biographies and tells a hugely important and often overlooked element of most male-dominated creative spaces.

“It was a goal of mine to make the story not about the music, but about the human beings with all their insecurities and vulnerabilities and giant egos and moments of doubt who created this music.”

“There’s this image of ‘the girl in the band,’ and we write whatever high-concept stories about ‘female rock stars,’ but it all feels kind of anodyne and remote,” Goodman explains, recalling her stint as the only woman in the Rolling Stone editorial office at the beginning of her writing career. There’s something powerful, she says, in watching Karen walk us through her experiences, “this person who happens to be female who also happens to be a genius in this incredible band at this incredible moment in time, exploring in this subtle and effective way the particularities of her isolation and vulnerability.”

Twenty years later and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs hardly look or sound like they’ve aged a day, as recently reiterated with their album Cool It Down—their first since 2013’s Mosquito, released only two years after Goodman’s account closes. But there are particular moments in Lovelace and Southern’s film that quietly remind us that these complex stories of sudden fame and the dangers of all its trappings are being carried out by individuals who were approximately the same age their debut albums are now, who injected culture at large with a much-needed course correction that continues to be followed to this day with the next generation of artists planning their own move to New York. “It’s kind of obscene that we were allowed to be let out of the house, to be honest,” Goodman admits. FL