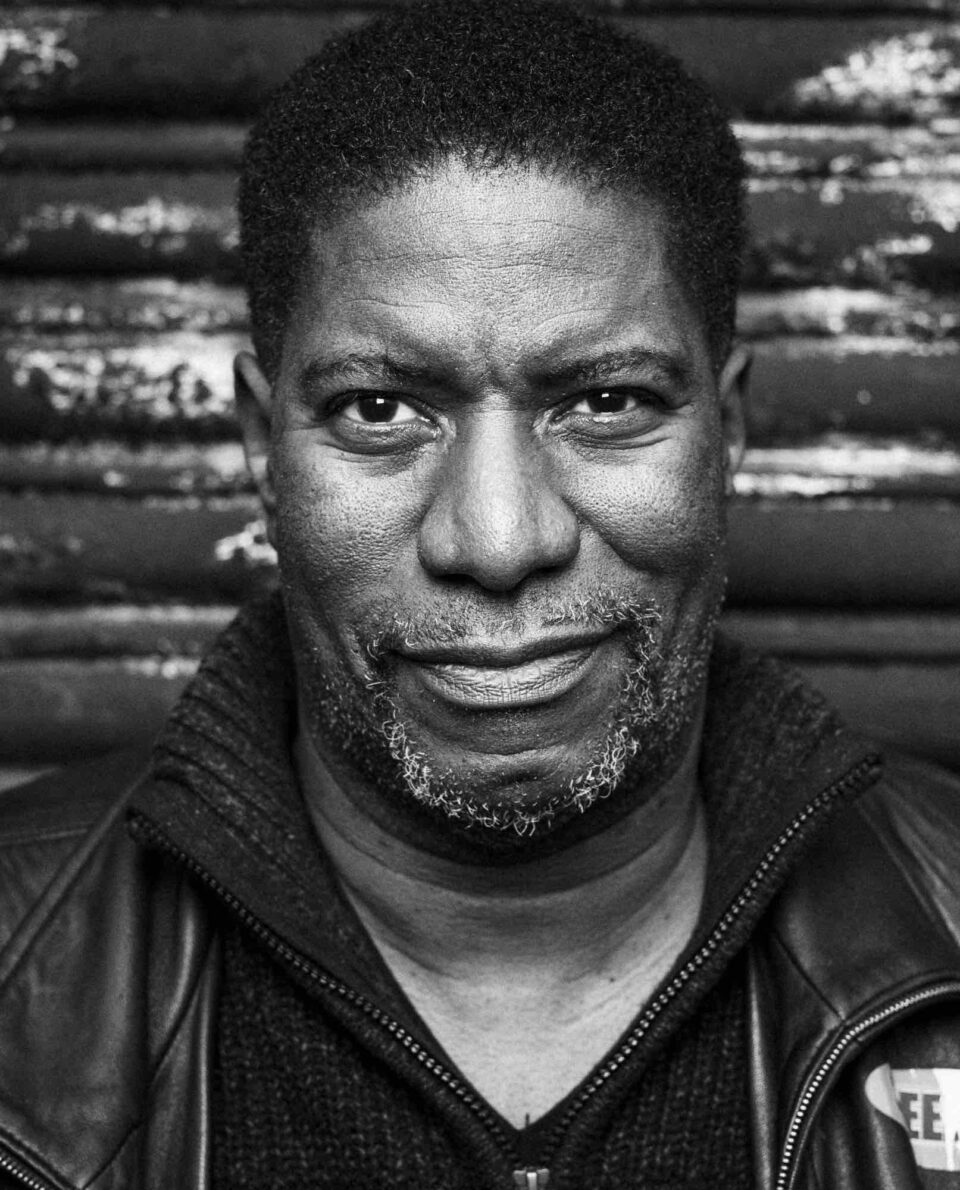

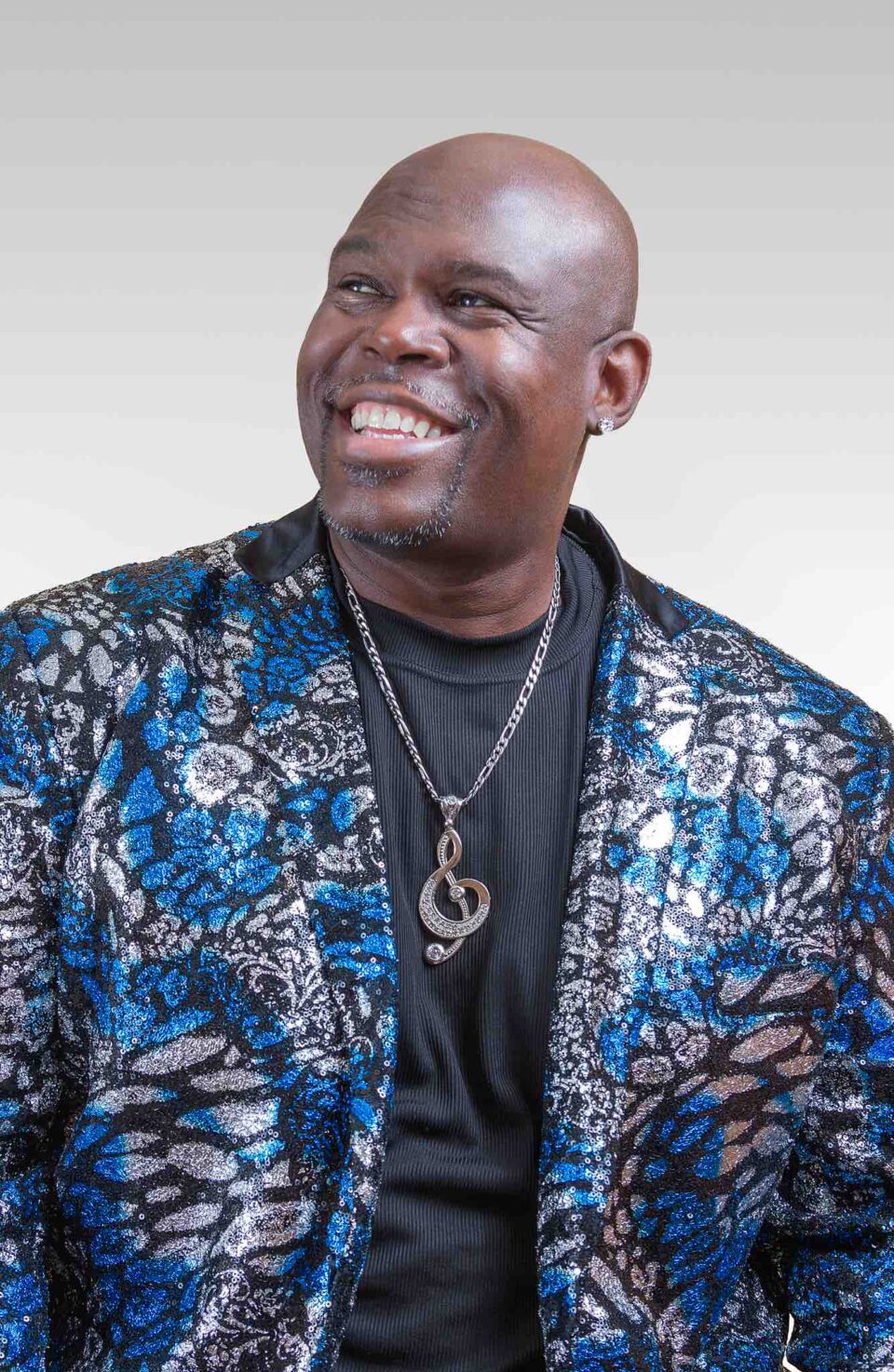

If Beyoncé, Drake, and Ava Max are all that millennials know of house music, it’s a moment for reflection and real schooling from two masters of heavenly electronic dance music who continue to ply their wily trade today: Ten City. Comprised of vocalist/lyricist Byron Stingily and producer/composer Marshall Jefferson, the duo have been working their richly melodic magic since 1987 with early Chicago house hits such as “Devotion,” “Right Back to You,” and “That’s the Way Love Is.”

First released by major labels such as Atlantic and Columbia, Ten City busted apart by the 1990s, only to reunite three decades later—first for the Ultra label in 2021 with Judgment, and now with Love Is Love on Helix Records. In both cases of 21st-century house, Stingily and Jefferson are playing to the music’s traditions while upping the ante of modernism and pop-chart songcraft.

With Jefferson calling from London and Stingily from Chicago, my conversation with Ten City starts the day after Beyoncé’s Renaissance wins a Best Electronic Dance Album GRAMMY. (“Having Beyoncé get that GRAMMY is positive,” Jefferson says. “Renaissance is excellent. She works just as hard, if not harder, than everybody else. Seniority in electronic dance music doesn’t mean a thing unless you’re jamming.”)

Throughout our conversation, the two old friends talk over each other, finish each other’s sentences, and are as charming as they are effervescent.

House music was built in Chicago as a communal process dedicated to all manner of under-served peoples. Do you still see what Ten City does as serving that community?

Marshall Jefferson: Yes, definitely. Not only are we playing to the community, but in terms of guest artists, we’re doing our best to fit as many of them on this album as we could.

Byron Stingily: When house started, Chicago was one of the most segregated cities in the country—not just Black from white, but Mexican, Puerto Rican, Polish, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, and so on. House music, where it was playing, was the one place of desegregation.

MJ: We even had people pretending to be gay just so they could fit in.

BS: And even if you look at our new album, it’s all inclusive—we have old-school house on Love Is Love as well as some Afrobeat, some pop, tech-house, Euro-house, R&B. We wanted to bring as many people and sounds together on this new album [as we could].

“After one of our closest friends in the house scene died, we knew we had to get together on something. Time is fleeting. Let’s do it, by any means necessary.” — Marshall Jefferson

Going back to the roots of Ten City, what made you want to be a band, as opposed to a solo act?

BS: Honestly, it was because, growing up, so many people would tell me that I didn’t fit the look of what an artist was. I’m 6'3", 240 [pounds], a one-time athlete, and built like a football linebacker. I’m a big guy. When we started, there was Prince and Michael Jackson, both small-built and slender with model-like features.

MJ: He didn’t have confidence in himself. That’s why he formed a group. The original record deal was supposed to be me and Byron, but he wanted to have a group. We had to split the money up 25/25/25/25.

BS: Marshall’s right about that. I’m more introverted than I am extroverted, and I thought that a group would be more interesting than just me standing in front of Marshall.

MJ: We actually had the deal, so his lack of confidence was unnecessary. We wrote our first hit, “Devotion,” on a double date. Byron just started singing to impress the women that night.

BS: Marshall doesn’t like me telling this part of the story: Marshall’s date actually stole my date that night.

MJ: Anyway. It’s all good.

Marshall, considering you were already a big-deal producer, what made you want to get involved with Byron?

MJ: “Funny Love.” He did this track with a group called Dance 7. I heard him sing, asked if he wrote the words, and when he said “yeah,” I said “let’s go.”

Walk me through the evolution of your four albums before Judgement and Love Is Love.

MJ: While the first album was great with everyone at the label and the band contributing, I think Byron once said that the second album was just…sometimes you just have to stay on the ride. Everyone was jockeying for the driver’s seat on that second album.

BS: On the first album, Atlantic gave us a small budget, told us to do that little thing you do, and get back to them when we were done. So we were in the studio having fun. After we did that first album, it became business. They kept throwing the success of Soul 2 Soul in our face. And Black Box—they kept telling us that we had to add elements of what they did into what we did.

MJ: The thing was that these other bands were copying off of us.

BS: We were the innovators of that sound, and honestly, it became very frustrating. I hate to sound cliché like this, but the music stopped being fun.

“When people used to go to house parties in Chicago, that was their church. They went to connect. Certain songs were relatable to their lives, and that was a form of release. We want our songs to be a release. To connect.” — Byron Stingily

MJ: The label wasn’t promoting us as they did their other acts—no video, no push for radio play. The first album went gold without any promotion from the label. Atlantic’s Black Music Department made its first profits since 1967 with our first album. That’s Aretha Franklin’s time. Basically, the label was able to earn because our budget was so low. Just our club play was a selling point. The second album? They held promotion over our head. “We’ll promote you if you do like Soul 2 Soul.”

Did things get any better when you did the fourth album at Columbia?

BS: What happened at Columbia is that we got caught up in label politics that had nothing to do with us. We signed, and the week after there was a change in leadership at the label.

MJ: When you lose your A&R backing, that’s the kiss of death. We were out in the middle of the ocean with nothing but a rowboat after that.

BS: The new person who came in for us at Columbia told us they didn’t understand our music. Columbia actually asked me to stay there and do a solo R&B dance album, but I left—went to an independent, Nervous, had top-40 hits in Europe, and actually got a chance to share in the licensing.

“When I was younger and working with Marshall, I used to think he was picking on me because he wouldn’t drive anyone in the same way he drove me.” — Byron Stingily

How did you get from doing nothing for 27 years as Ten City to doing two new albums almost back-to-back with Judgement and Love is Love?

MJ: It was [Helix Records owner] Patrick Moxey believing in us. He wanted to give us a shot.

BS: I called every label to ask if they would release a new album from Marshall and I and they were all like, “Send it to us when you’re done.” I was about to take my own money and record it when I got a call from Patrick saying he was coming to Chicago. I thought he was here to sign some new, young act, but when we sat down, he said he had an urge to record a new Ten City album. The only things he asked us to do was include new versions of “Devotion” and “That’s the Way Love Is” on it, and that Marshall and I had to be completely involved. I joked that I hated Marshall and refused to work with him, just to let him hang for a minute. Marshall’s my brother and I would’ve done anything, anytime with him.

MJ: After one of our closest friends in the house scene died, we knew we had to get together on something. Time is fleeting. Let’s do it, by any means necessary.

What would you say carries the past of Ten City into the present?

BS: We both have a different love of different music. Marshall loves Led Zeppelin and AC/DC. I love Chicago soul classics like Curtis Mayfield. Marshall can write beautiful melodies on his own. I went to school for psychology and I try to write stories that connect people. When people used to go to house parties in Chicago, that was their church. They went to connect. Certain songs were relatable to their lives, and that was a form of release. We want our songs to be a release. To connect.

Byron, can you talk about singing in the eye of the hurricane of Marshall’s music? Listening to your evolution from past to Love Is Love, I’m reminded of Jimmy Scott and latter-day Sarah Vaughn.

BS: Eddie Kendricks. Curtis Mayfield. A group like The Stylistics and Enchantment. Sylvester. Isaac Hayes. The blues. Dirty Mind era Prince. Lee John from Imagination. Talking Heads. I’m channeling different energies. Female energies, too, such as Aretha. I listen to what a song needs. I couldn’t have done this successfully going on 40 years if I had to do songs only one way. Lee John might come up to me and slap me, ask me to leave his vibe alone, but no one wants to have the same look all the time.

Marshall, how do you write differently for Byron or a Ten City song than you would your own solo stuff?

MJ: Byron is more talented than the other singers I’ve worked with. He comes up with great ideas off the cuff. Often, I feel as if I’m trying to catch up, but that’s OK. When we do write together, the stuff is nice.

BS: We push each other. If I have to play a song idea for Marshall, it had better be great. Because he’ll tell me if it’s mediocre, and that we must do better. Fact is, when I was younger and working with Marshall, I used to think he was picking on me because he wouldn’t drive anyone in the same way he drove me. He’s a big bully.

MJ: I knew you could take it. FL