Here comes Skip. Pedaling his bike through a sunny, San Fernando Valley suburb. At first all we see is him, resplendent in early-’80s shopping mall fashion. Blue sweater vest, waaaaaay too tight chinos. We hear the clicking of his bicycle chain as he cruises the empty afternoon streets.

We’re about halfway through Martha Coolidge’s 1983 masterpiece Valley Girl. It’s got a terrific, wall-to-wall soundtrack from the likes of The Plimsouls, The Payolas, Josie Cotton, Men at Work, The Flirts, and, of course, that gorgeous falling-in-love montage set to Modern English’s “Melt with You.”

But now here’s a scene featuring a side character who doesn’t figure into the overall plot at all. Skip, played by David Ensor in his one and only screen performance. You see, he’s been having this flirtation with a suburban mom, a sultry-as-hell Mrs. Robinson type played by Lee Purcell. Her daughter—played by the criminally underused pixie sex bomb Michelle Meyrink—is about to snake this young buck right out from under her mom’s talons, once Skip gets over his hesitation and enters the house.

Which he does. But not before wavering for a moment, doing a half-hearted retreat-and-reverse on his 10 speed.

I’m setting this visual up so I can talk about the most startling moment in the scene. Because, after the four seconds of establishing bike-chain-clicking, birds-chirping ambient noise on the soundtrack, Sparks’ “Eaten by the Monster of Love” blasts onto the soundtrack.

And it’s a jolt. Russell Mael’s a cappella vocals, urgently chanting, “Don’t let it get me, don’t let it get me!” almost in rhythm to Skip’s pedaling. It’s as if Sparks is a horny teenage Greek chorus—how can I get laid without getting snared into a relationship? It’s such a perfect summation of the world our two main characters—punk Nic Cage and Val-gal Debra Foreman—have to navigate on their way to actually falling in, like, for real love.

That was my first introduction to Sparks. Dropped like a sonic grenade into the middle of a wiser-than-it-looked 1983 teen sex comedy. Their more lyrical (if equally cynical) “Angst in My Pants” also shows up on the soundtrack, but the way “Eaten by the Monster of Love” is given its own screen entrance? Like a hopeful young star who proved to be too original, too unmanageable, to ever find a niche and burst through as a major star. They’re unforgettable. They’re also uncommidifiable.

For me, it was fanboy at first listen.

Sparks was always there, for the next 40 years, putting out album after album, building the kind of fanbase that realizes the object of their affection will never go mainstream and thus loves them even more for it.

And even more miraculous? Sparks have remained joyful, hopeful, and giddy about the decision they’ve made. They chose being able to innovate and explore for decades over a more massive fanbase with expectations—the kind of expectations that keep a lot of artists repeating versions of their first two or three years for the length of their professional lives. Sparks’ fanbase—which, now, ironically, can fill the Hollywood Bowl—has zero expectations of Ron and Russell, the ever-shifting, ever-surprising Mael Brothers.

Sparks was always there, for the next 40 years, building the kind of fanbase that realizes the object of their affection will never go mainstream and thus loves them even more for it.

It’s a testament to quietly sticking to your guns, to loving what you’re doing, and to not being afraid to sometimes switch your gun with a spatula or rubber chicken, to see what will happen. Edgar Wright’s superb documentary The Sparks Brothers brought in a younger contingent of Sparks fans. But unlike other niche acts with rabid followings, Sparks fans didn’t resent the late-comers. They were glad to have new friends—new fellow obsessives—and knew that the wildness of the overall discography would chase off the looky-loos sooner than later.

Patton Oswalt and Sparks Brothers director Edgar Wright

Watching The Sparks Brothers documentary at the height of the pandemic was a life preserver. Being locked inside the house for so long, fighting the existential panic of thinking the years were running away and taking my creativity with them, my brain started to eat itself. Would there be anything left when and if I emerged back into the world? Was I burning all of the artist-fuel on dread and confusion?

Turns out I had nothing to fear. Because there were Ron and Russell, reminding me without telling me that your brain can be a lifelong feast with plenty left over for whatever you might conceive and execute. But you have to be excited about the process of creation first, of the inner moments of discovery and connection that you make before any audience applauds you or critic lauds you. When you listen to the music you can hear the fun they had imagining it and making it real long before you showed up. And they’re as excited to re-experience it again, and you are more than welcome to take the journey with them.

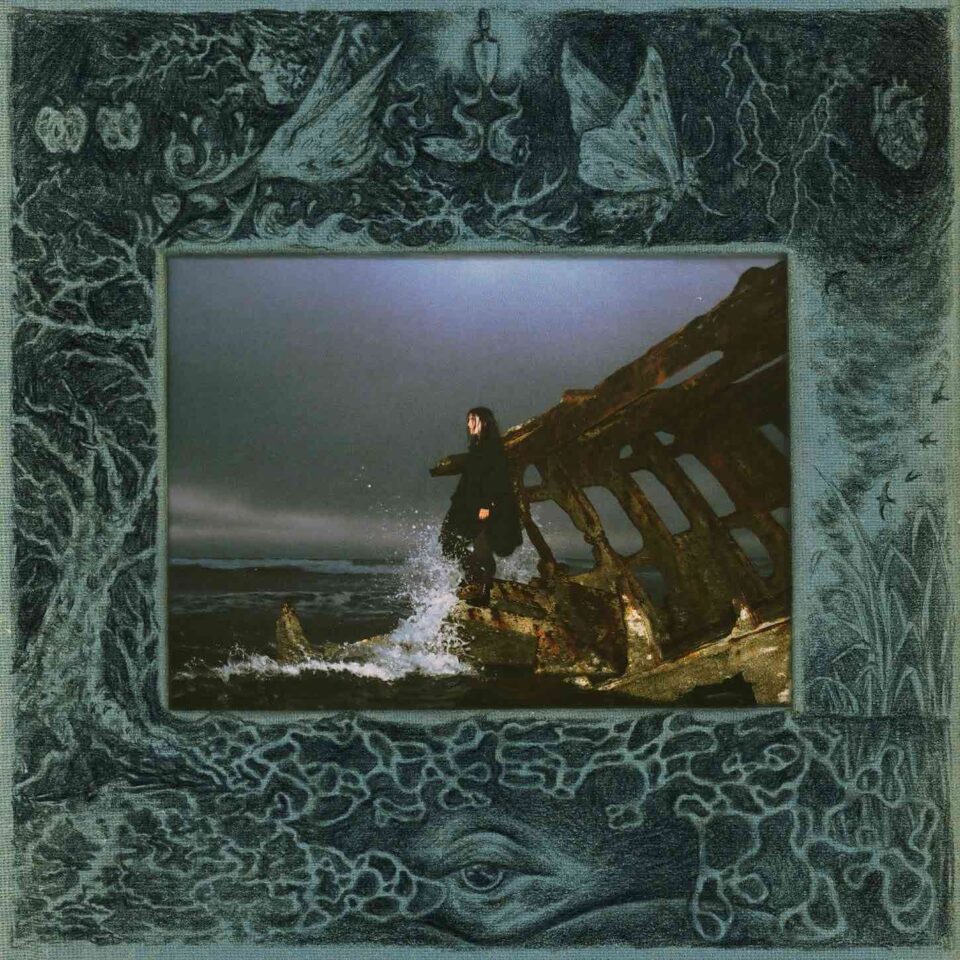

So start listening to Sparks. Start anywhere. Start with their '70s stuff, their '80s stuff, the soundtrack to Annette, or their new album The Girl Is Crying in Her Latte. Go forward and backward—because they did. Their music is a testament to letting your mind roam and reel and combine sounds and ideas that are surprised to find themselves together. Sparks lit a thousand flames—now it’s your turn to burn bright.

Do let them get you. FL