Jean-Michel Basquiat and his culture-jamming, hip-hopping, neo-expressionist, post-punk, end-of-days, Warholian-pop-art, death-knell brand of graffiti-inspired art has so long been the province of New York City and its 1980s that to consider it elsewhere—namely Los Angeles—is disconcerting. Yet according to Jeanine Heriveaux, one of Basquiat’s two sisters (Lisane Basquiat being the other) behind the familial vibe and curatorial vision of Basquiat: King Pleasure—opened at The Grand in Downtown LA in time for April Fools—the painter and musician she called brother loved the sun and shadow of the City of Angels.

After the installation’s lengthy run at the Starrett-Lehigh Building in New York City, Heriveaux believed it was the West Coast’s turn at everything SAMO. “We always stated that the intention of the exhibition was to show parts of Jean-Michel’s journey that haven’t really been discussed before,” says Heriveaux. “Since Jean-Michel spent some time in Los Angeles, we thought it was important to weave this part into the narrative. As we started talking with people he was around during his time spent here, we learned quite a bit and decided to share it.”

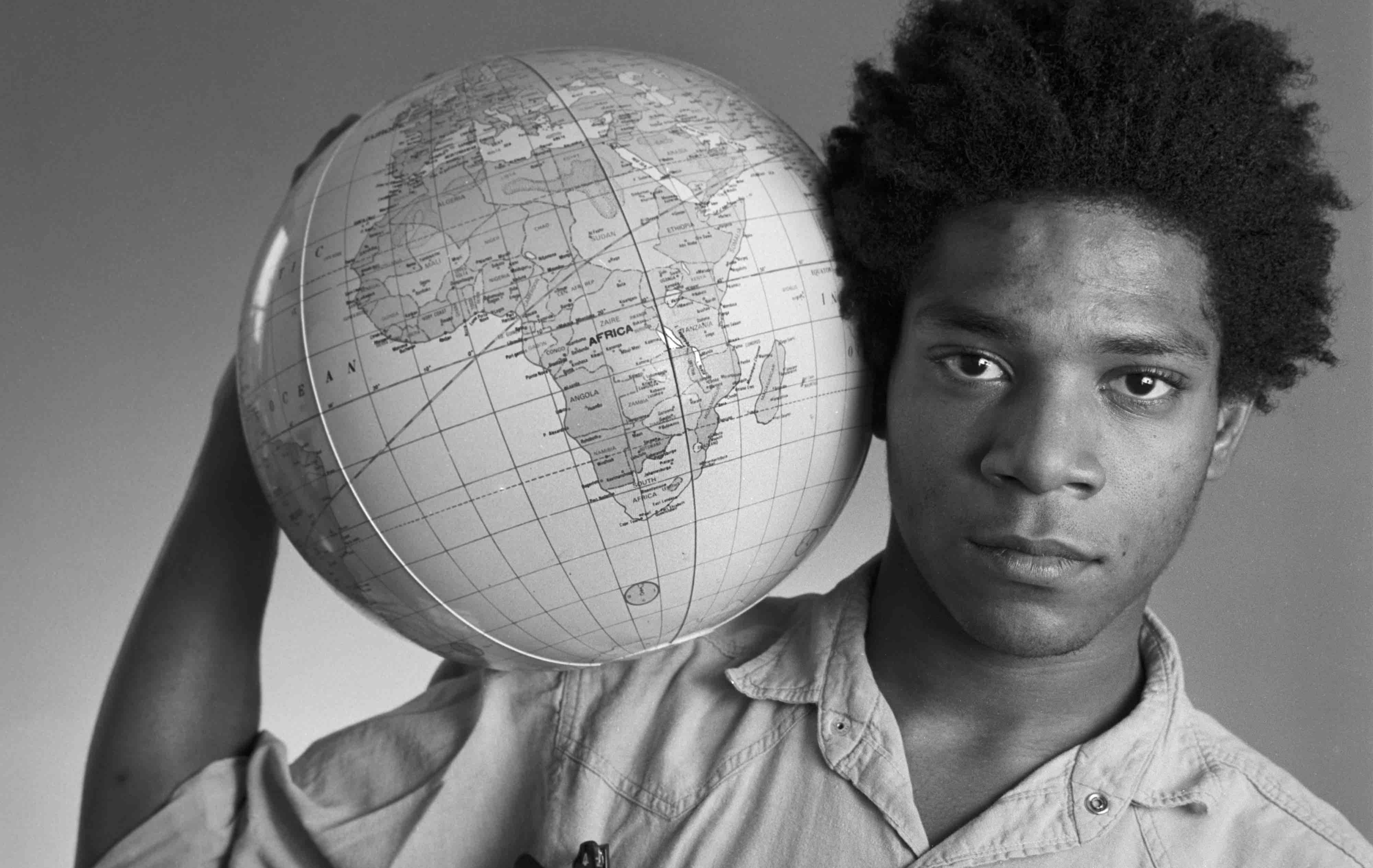

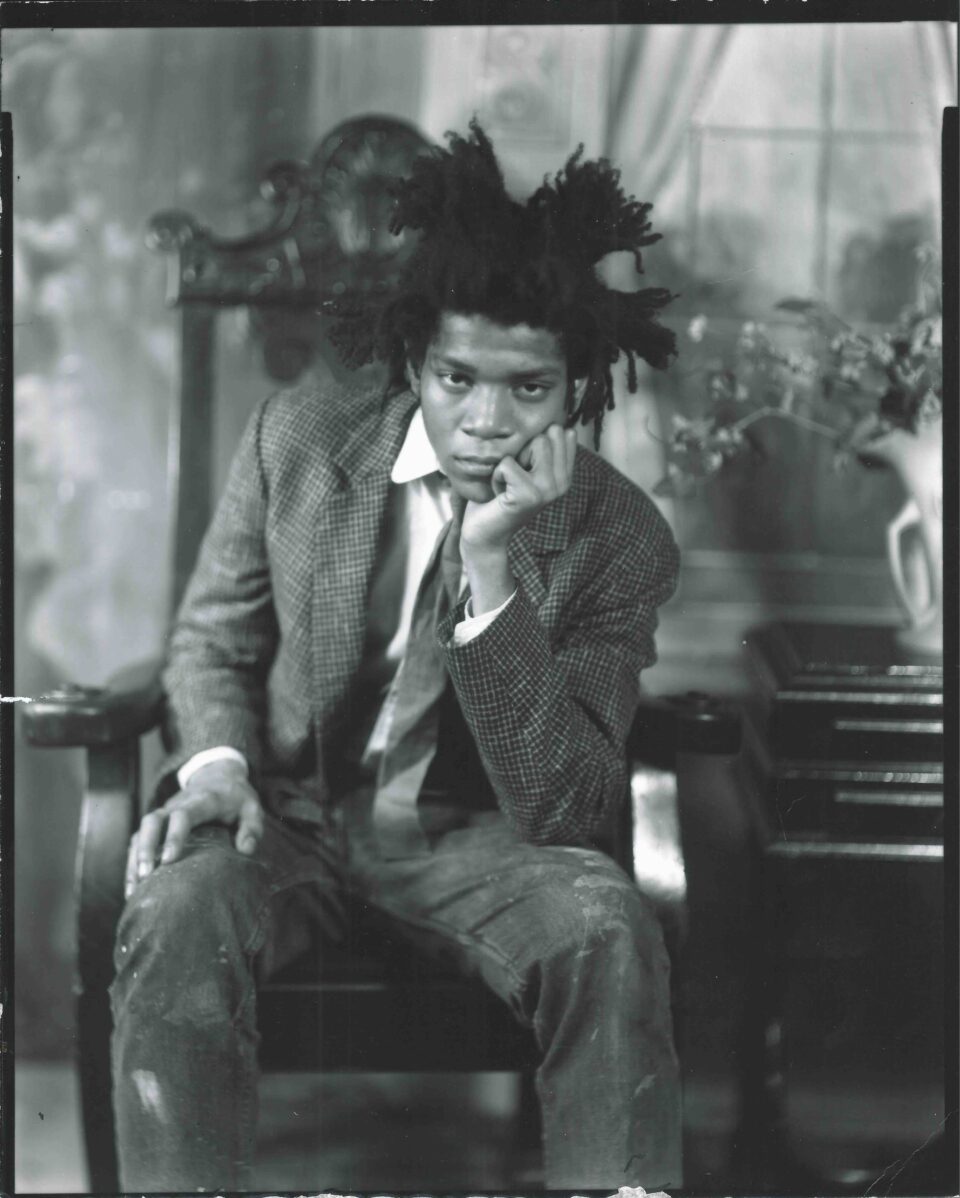

photo by Lee Jaffe

Considering the breadth and length of NYC’s seemingly unending display of colorful paintings, sketches, and re-created environments crucial to the artist’s raison d’etre, Heriveaux wanted to make Downtown LA’s Basquiat: King Pleasure an equally sensory-overloaded experience. “The main difference of the exhibition in Los Angeles is the layout and flow,” says the young sister Basquiat. “Instead of being in one 14,000 square foot space, the exhibition is spread between four spaces with a courtyard, and the guest has the ability to freely roam between each space. There are also small Easter eggs added from his trips here.”

To this writer, there is no finer Easter egg when it comes to presenting King Pleasure in LA than welcoming hometown-hero-turned-Basquiat-friend-and-contemporary Kenny Scharf to speak as the first part of the “Live from the Palladium” roundtable conversation series with Larry Gagosian, Tamra Davis, Jeffrey Deitch, Fred Hoffman, and more. While their first two panels take place on July 14 and August 9, the exhibition/installation itself has been extended through October 15 due to popular demand.

“Since Jean-Michel spent some time in LA, we thought it was important to weave this part into the narrative. As we started talking with people he was around during his time here, we learned quite a bit and decided to share it.” —Jeanine Heriveaux, Jean-Michel’s sister

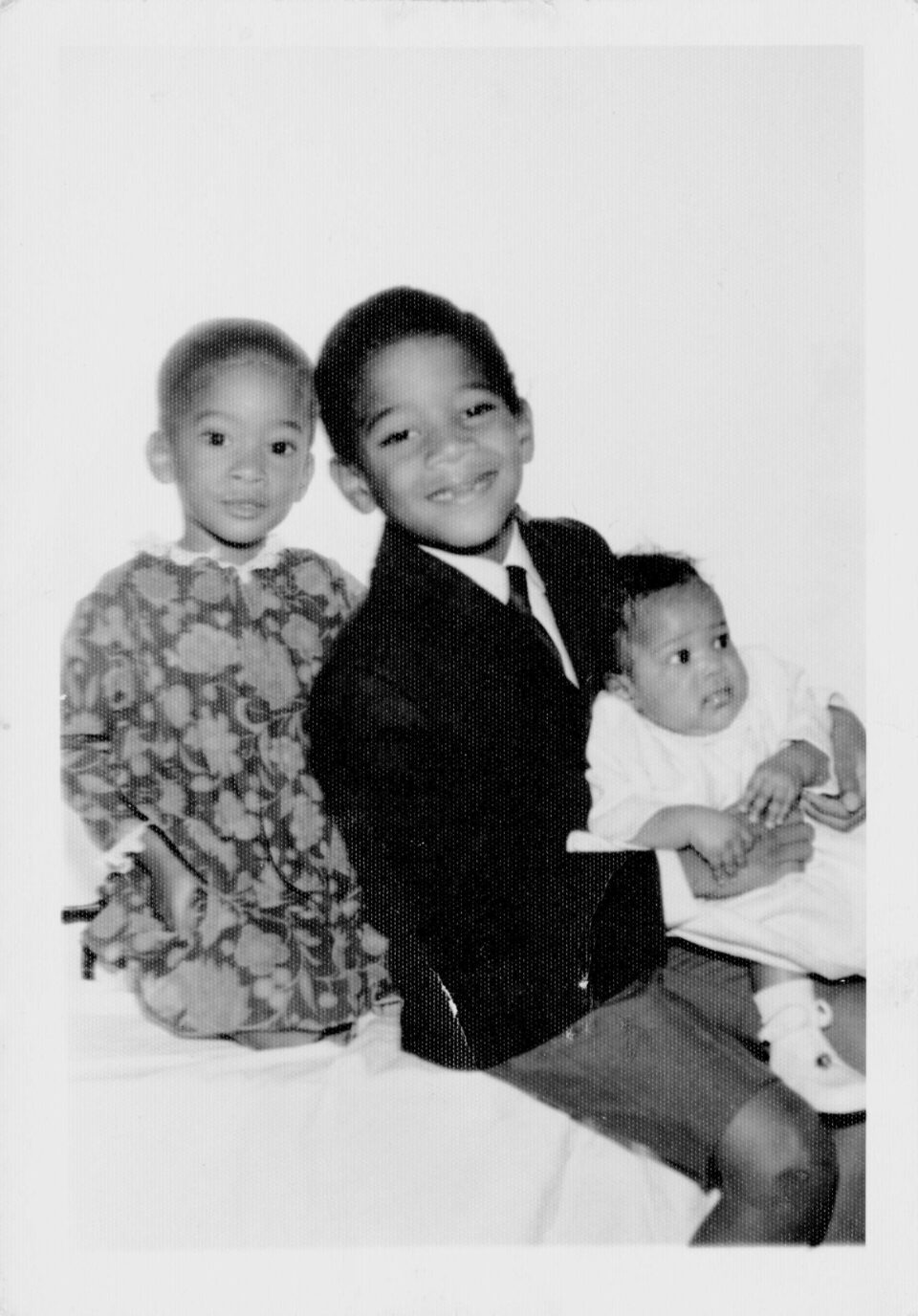

Basquiat family / photo courtesy the estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

Scharf, the last man standing of the unholy East Village trinity that included fellow DIYers Basquiat and the late Keith Haring, left his home in Los Angeles just in time for NYC’s last great nightclub/gallery renaissance. Once there, along with befriending Basquiat and making a roommate out of Haring, Scharf created his signature large-scale walk-in work Cosmic Cavern. These immersive black light and Day-Glo paint installations, along with other blobby, cartoony, graffiti-esque works, were just the start of Scharf’s importance as a crucial new voice in American art—something that would make him into a downtown gallery and uptown museum star at the same time Basquiat’s star was rising. And while Basquiat passed away in 1988, adding to his legend, Scharf stayed alive and did likewise.

We spoke with Scharf about the good old, bad old days, and the effect that his friend and contemporary Basquiat had on the art of the 21st century and beyond. Tickets are still available for King Pleasure here.

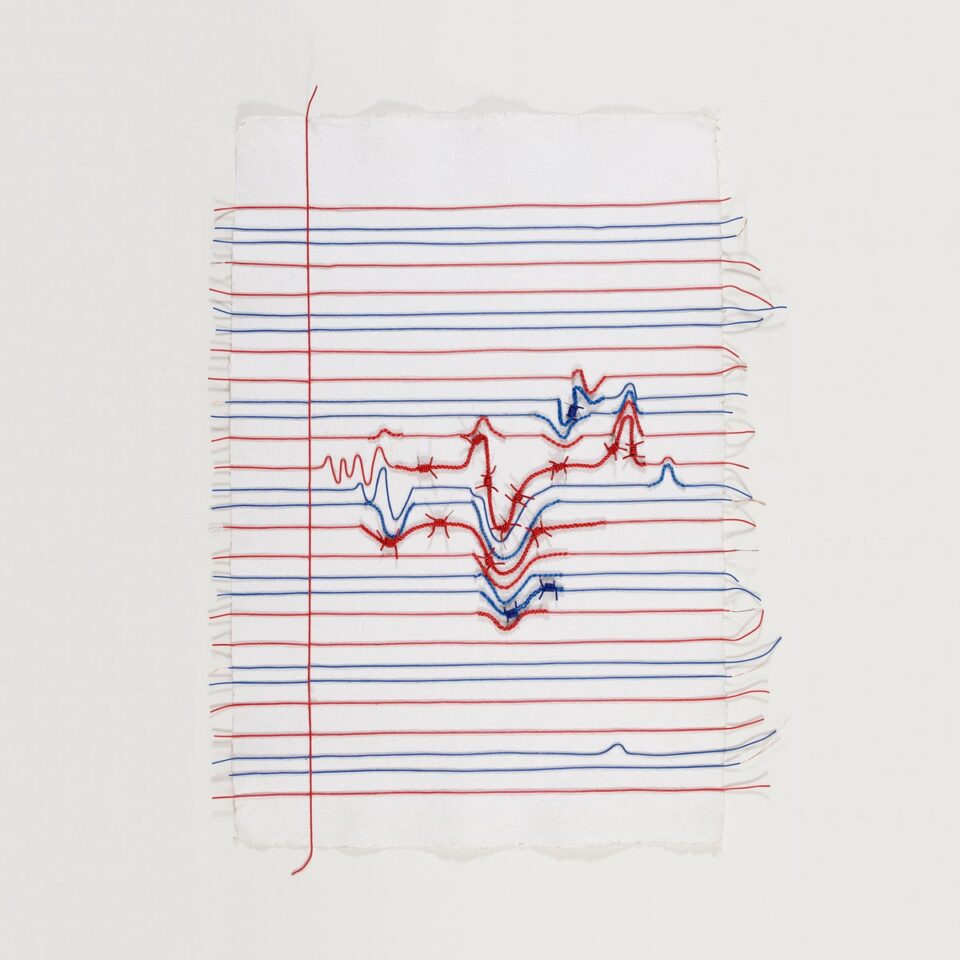

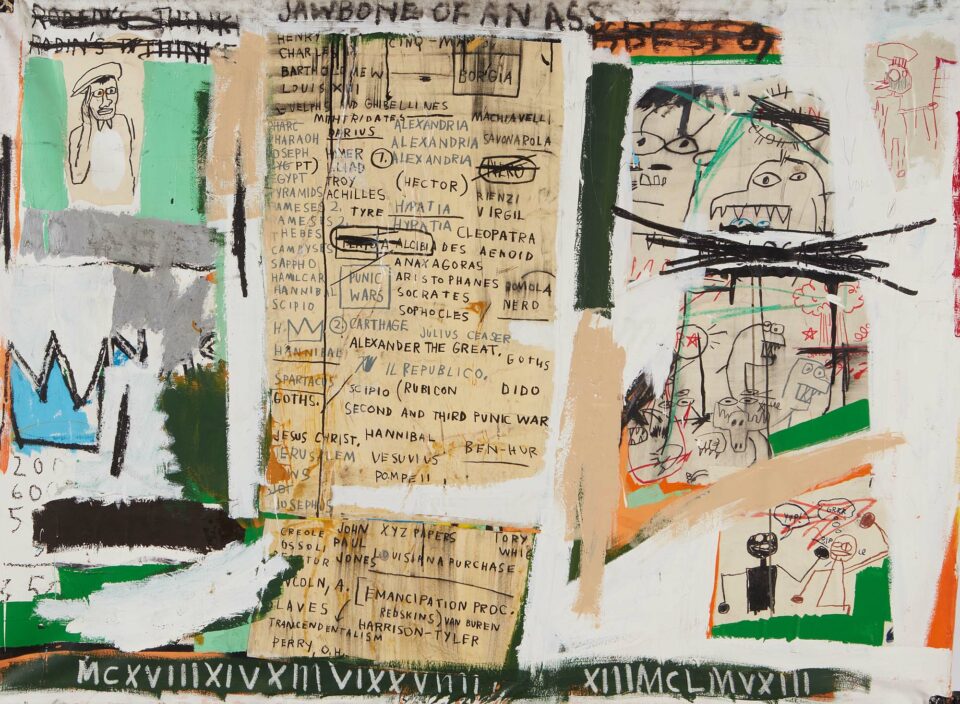

Jawbone of an Ass, 1982 © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York

As the last man standing in the grand graffiti-inspired aesthetic that birthed you, Haring, and Basquiat, what can you say now regarding the kismet or zeitgeist of that visual vibe?

I can say a million things about it. I can say I knew it was something big, exciting, and important, yet totally free, unplanned, and improvised. Looking back decades later, facing the intense popularity of this time, this work is more relevant than ever. It was so DIY. As we get more technological, people will be romanticizing this moment more and more. I think this is because soon after MTV and the internet arrived, things changed forever.

How do you believe that what you and Basquiat did changed the then-present of art?

I think we were defining a new way of being an artist; making our own rules, and trying to break down some walls. I think artists are always trying to do this. Everyone wants to get in the door.

Charles the First, 1982 © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York

“I always looked to Jean as an artist, to watch every painting and creation that I could. Everything was electrically charged with wonders.” — Kenny Scharf

How do you believe that your friendly camaraderie with him pushed Basquiat for the better?

I always looked to Jean as an artist, to watch every painting and creation that I could. Everything was electrically charged with wonders. I cherish the healthy and sometimes unhealthy competition we had. It’s always lucky to have your competitor/friend be on the level of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Is there something notable you can recall about your first meeting with Basquait that may have been a portent to things to come?

The first time I saw him was in the cafeteria at the School of Visual Arts. I was walking by with my portfolio and I had some small paintings inside. He really locked eyes on me and said, “What’s in the portfolio?” He didn’t even introduce himself or anything. So I showed him this painting and he said, “You’re gonna be famous.” It was very strong and was not something I expected someone to be saying.

Then, the next day or maybe that afternoon, I went over to where Jean was staying and I saw some collage on the wall that I’ve never seen since. It probably doesn’t exist anymore. It was so startling and stunning. It was this image of the assassination of JFK, the Lincoln Continental, Jackie, and, of course, JFK, the gun and all. It was all these cut-out pieces from magazines, drawings, and scratches in paint. I was blown away. There was an energy that bounced off that piece of paper and that continues to stun me in such an exciting way to this day. I can remember it like it was yesterday, and it was 1978.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jailbirds, 1983. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

How do you believe that Basquiat’s relationship with Warhol—which was so much a part of the NYC installation—turned the nature of his art or business around?

Although I was at the show at the opening, and I was very aware of the collaboration and remember so clearly the images, and was frankly jealous of all their attention, I loved it. For real. About the business side, I was so concentrated on trying to get my own business going at the time that I assumed his business was going very well. I’ve never been one to know that much about my own business, let alone another artist’s. So I don’t know if I can answer that.

What is the West Coast view of Basquiat in your opinion—especially as it’s reflected in the Los Angeles iteration of the exhibition?

I remember times when I’d be back in LA visiting my parents and Jean was in town. He seemed to be doing really well. He had his Gagosian studio, and Madonna. Those years my relationship with Jean was sometimes strained, although still laced with occasional ups. I can really recall my fondest memories and times with him to be back when we were both teenagers, wandering the streets of New York.

Untitled (Thor), 1982 © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York

Untitled (100 Yen), 1982 © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York

Can you tell me something about your relationship with Basquiat that most people wouldn’t expect, that may help audiences understand what they’re seeing in LA?

Don’t even go there—I know too much [laughs]. Although Jean was not a student at the School of Visual Arts, he liked to hang out in the cafeteria and meet other artists. So he would get into the building and draw his SAMO all over, and we loved it, Keith and I. Then there was a little bit of a “Watch, don’t let this guy in anymore because he’s writing on the walls.” And so he said to me, “They won’t let me in,” and I said “OK,” and I forged my teacher’s signature and a note, and the guard let him in. He went nuts! All over everywhere, and let’s just say it was even harder for him to get in after that. FL

photo by James Van der Zee Archive / The Metropolitan Museum of Art