Whether as the co-founder of Pink Floyd or on his own in the darkness of abstract art-rock as a solo act, guitarist, songwriter, and vocalist Syd Barrett was a bold anomaly. With his clipped, deadpan voice, his free-guitar scrawl and its reliance on feedback, echo, and distortion, and a lyrical, strictly stream-of-consciousness melody-making style—to say nothing of his wooly fashion—Barrett all but invented British psychedelia in his image; an English eccentric equivalent to stateside psychotropics such as Roky Erickson, Mayo Thompson, Paul Kantner, and Skip Spence.

For all of the whimsy, woe, and spaced-out oddity of his music with Pink Floyd (1967’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and, to a far-lesser degree of contribution, 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets) and his threadbare, childlike solo efforts (The Madcap Laughs and Barrett, both 1970), Barrett’s inventions are often thrown under the bus of his personal struggles with mental health issues and druggy, psychogenic fugue states. With the newly released, emotionally immersive documentary Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd from director Roddy Bogawa (with the late Storm Thorgerson, the legendary album cover designer and Hipgnosis co-founder), the music of Barrett is given greater clarity (as if clarity was necessary) and import while putting his magical (and not-so-) story in perspective courtesy of the people who knew and loved him.

While Have You Got It Yet? gains that perspective from Bogawa’s shaping of the film’s rare footage, and from on-camera interviews with Barrett-era contemporaries such as Peter Townshend and remaining Floyd members (the otherwise-never-unified David Gilmour, Nick Mason, and fellow co-founder Roger Waters), Barrett’s wild-eyed aesthetic vision gets its fullest portrait in my brief conversation with the director, alongside one of Barrett’s greatest acolytes: Robyn Hitchcock. For Hawaiian-born, one-time Angelino punk Bogawa (his first documentary, I Was Born, But, was dedicated to that LA existence) the post-Syd Pink Floyd was the very first concert he caught as a teen. “My father drove a friend and I to Anaheim Stadium, dropped us off in the parking lot, and said, ‘I’ll meet you here in 11 hours or so.’ Ahh, the ’70s…” he recalls of the night’s surround-sound effects and pigs with laser light eyes floating overhead.

“Growing up in Los Angeles, I was an early swimming pool skateboarder—skating with Tony Alva, Jay Adams, and the Z-Boys at Paul Revere, Kenter, and various pools,” he says. “My friends and I were heavy into Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, and Black Sabbath. I remember Ted Nugent was played a lot at the pool sessions back then, before Black Flag, and when I started going to clubs in Hollywood to see all the new punk bands at the Starwood. It was there that I suddenly started thinking about my identity. Being among the misfits in the punk scene and its whole ethos of ‘just go out and do it’ altered how I thought of the world.”

“To me filmmaking is about relationships. So I think it’s always important that somehow that comes out through the material. Emotion is often more important than information.” — Roddy Bogawa

Looking at identity and what happens when it melts away as a starting point for Have You Got It Yet?—named for Syd’s repeated queries to his fellow Floyd members after being unable to play a song the same way twice—allows me to question whether Barrett’s descent into madness is more of a finite, bracing feature than Pink Floyd’s ascent without him. “You do have two things that happened in parallel,” says Bogawa. “While Syd becomes more of a cult figure, Pink Floyd becomes one of the biggest bands in the world, writing some of their most beautiful music—some of it about their long-lost friend. That’s utterly fascinating; myth-making to the core. Pink Floyd were always fairly private about their personal lives, but certainly Syd’s ‘disappearance’ from the music industry while leaving these two rather poetic, raw, and exposed solo records is fascinating on many levels. At the core, the story of Syd is a story that’s unresolved.”

As it was Barrett who co-founded Pink Floyd with Waters, welcomed Mason, then brought in Gilmour when Syd slowly disintegrated, it’s perfectly natural that—among the old-friend interviews, grainy British television footage, and black-and-white band photos that litter Have You Got It Yet?—the most poignant moments of Bogawa’s documentary come in conversation with the remaining band members who never speak with each other beyond lobbing insults.

“Roger Waters says in the film how Syd was the most ‘curious’ person he ever knew, and Storm told me once he thought Syd was channeling some muse that even he didn’t understand,” Bogawa says. “That Roger, Syd, David, and Storm all grew up together in Cambridge as childhood friends is definitely something which unites them going through the typical experiences of growing up together, and that shared moment is something that bonds all of them. Certainly Syd’s musical ‘curiosity’ was something that pushed Pink Floyd into another realm of possibility as a band. If you mean uniting them in the present, yes, in some way, the shared memory of Syd is about their youth, too.”

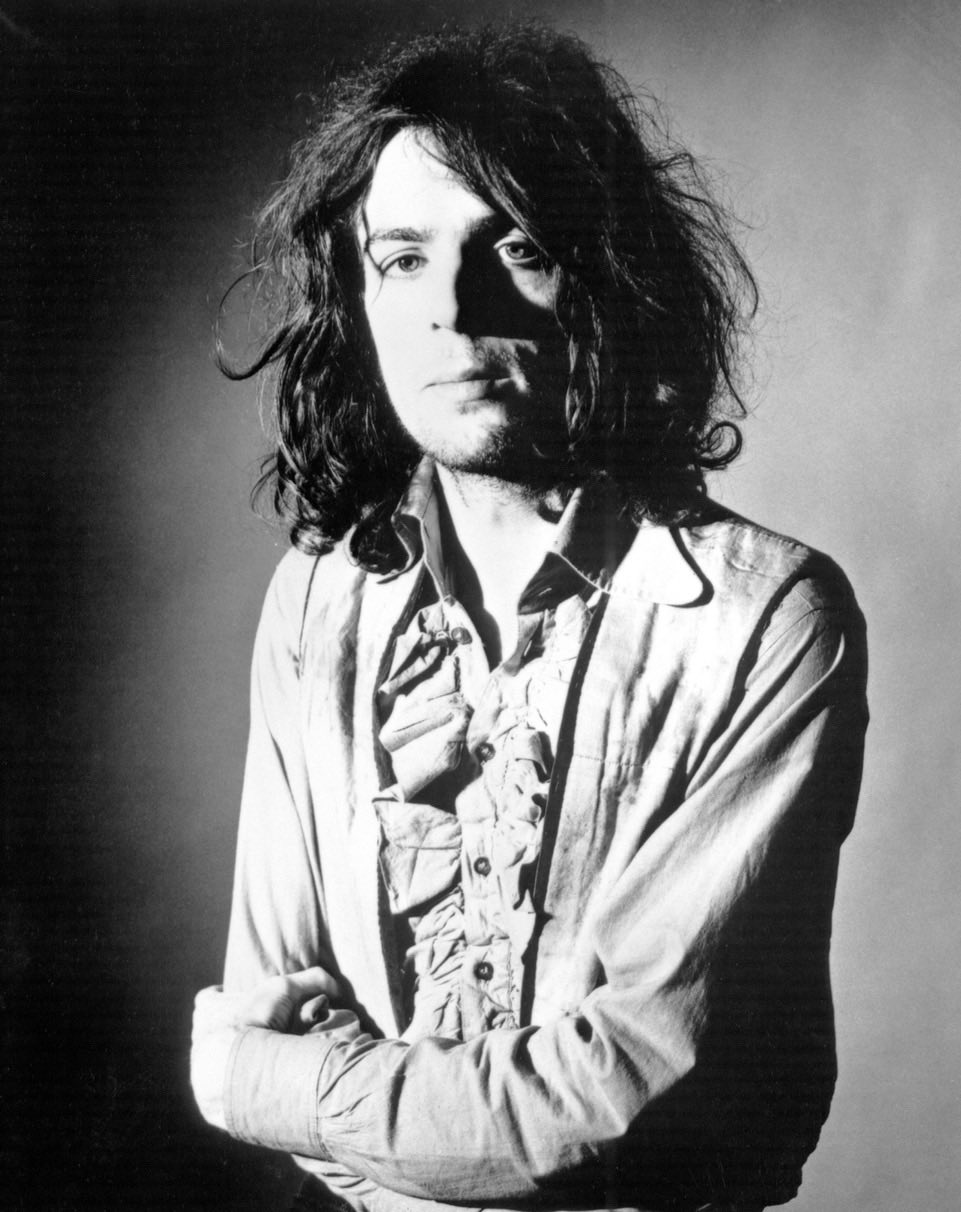

photo courtesy of Syd Barrett Archive

“While Syd becomes more of a cult figure, Pink Floyd becomes one of the biggest bands in the world... That’s utterly fascinating; myth-making to the core.” — Roddy Bogawa

Adding to that sense of shared memory in the film is the direct conversation between directors Bogawa and Thorgerson and the Pink Floyd brain trust. One of their main goals in doing the doc was to do the “inside” story of Syd, since Storm grew up with most of the people in Barrett’s cosmos. “When Storm let me start making the film on him, everyone around thought we had known each other for years, though we had literally just met,” says Bogawa. “There was something in our personalities that just clicked. Though Roger hadn’t seen Storm in decades, they hugged and he gave us an amazing interview. I was friends with Mick Rock [one of solo-Barrett’s earliest photographers], so we already had a relationship and in fact got Storm and Mick together for tea the last time Storm came to New York. It was amazing as they hadn’t seen each other since the ’70s. I also believe part of your job as a director is to go beyond the standard questioning and pat answers, and to me filmmaking is about relationships. So I think it’s always important that somehow that comes out through the material. Emotion is often more important than information.”

Continuing along the lines of catharsis, Bogawa considered that some of his movie’s footage—the British pop shows, a creepy American Bandstand appearance—that portrays Barrett’s rapid decline still falls second to images of cheer and the wonderful whimsy of his lyrics. “Mick mentioned how even during the Wetherby Mansions days, when Syd was becoming more reclusive and withdrawn, there were these photos of him with a beautiful smile,” says Bogawa. “The promo for ‘Jugband Blues’ is emotional for me because there’s an overwhelming feeling that he doesn’t want to be there and he’s becoming ‘the scarecrow,’ but it’s also affecting because of the lyrics he’s singing which show he was aware of what was happening around him. Watching that video saddens me knowing this was probably the last thing he’d do with the band. And the last line of the song: ‘What exactly is a dream? And what exactly is a joke?’”

Ever since his days leading The Soft Boys, English songwriter Robyn Hitchcock has led the charge for freak-folk melodies touched by frenzied psychedelic zeal and elegantly surrealistic lyrics touching either on the caustic or the charmed. And with that, Syd Barrett has been Hitchcock’s North Star, from his start through to his recent album Life After Infinity. “I was drawn strongly to Syd’s later songs: his final album just swallowed me whole,” says Hitchcock of the erudite, eccentric nature of the Floyd co-founder’s odd and childlike lyricism. “I don’t know if I ever came out the other side! The words, the notes he sang, the way he sang them, the guitar he played—it was all so right.

“Word-wise,” Hitchcock continues, “the way he interfused his abstract word-scapes with poignant heart-cries—like ‘Inside me I feel alone and unreal’—it’s so natural and unforced. He had a real gift for beauty, coupled with a drive to maroon himself beyond the reach of human help, and sadly his story often eclipses his amazing work. Where the other guys seemed to labor hard to write and polish their music, Syd’s just landed on him in a flash—or that’s the impression I got. Creativity came as naturally to him as opening a cupboard door. Until one day it wouldn’t open any more.”

“I was drawn strongly to Syd’s later songs: his final album just swallowed me whole... The words, the notes he sang, the way he sang them, the guitar he played—it was all so right.” — Robyn Hitchcock

Recalling his initial turn toward Barrett, Hitchcock first recalls another magnetic lyricist toward whom he looked to as inspiration. “I’d wanted to be Bob Dylan for about five years, but I wasn’t a Jewish kid from Minnesota,” he says. “Then, one damp chilly Christmas in the early 1970s, I got hit by the Barrett bus, and I discovered that we had a British equivalent of Dylan: a curly haired visionary enfant terrible on a burn-out streak—only Dylan never really burned out. And even as Barrett faded, I did my utmost to become him. Not the smartest career move, perhaps, but quite an experiment; and in the end I think I produced some good songs out of it, songs that did justice to my influences yet that were all my own.”

Taking into effect the wealth of differently wonky, yet often pointed Hitchcocks that have emerged since his 1981 solo debut (with 23 studio albums between that and 2023’s Life After Infinity), it would be no shock to imagine moving past his earliest inspirations. So, what of Syd Barrett lingers longest? “Syd remains part of my DNA, like Dylan and The Beatles,” says Hitchcock, noting how “those animal songs of Barrett’s” (“Wolfpack,” “Rats,” “Terrapin,” “Octopus”) are still among his all-time favorites. “There will always be glimpses of him in the songs and music I write. Ironically, Syd himself vanished 50 years ago or more, and he reverted to being Roger, an art student. For the rest of his life, people kept knocking on Roger’s door looking for Syd, but Syd was long gone.” FL