A few years ago, thinking myself wise in that cocksure way the young often do, I penned the following thought about The Fugitive, a film I’ve seen many times and have always thoroughly enjoyed: “Pedestrian pot-boiler designed to spend perpetuity on network television that’s worth watching for Tommy Lee Jones as a cantankerous, ever-lucky agent who, with his team of colorful companions, always seems to be in the right place at the right time, but can never catch a tired doctor.”

Having recently rewatched the film, which I’d come across on AMC while flipping channels and watching it for the familiar comfort—commercials and all—I had a change of perspective. I ruminated on why I and many others can watch this film again and again and never get bored. It was an immense hit, getting nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars and making $184 million, the second-highest grossing film of 1993 domestically, the year Jurassic Park became numero uno of all-time. It isn’t flashy or bombastic like modern escapist fare, and it wasn’t made by a name-brand auteur (Andrew Davis made the Steven Segal actioner Under Siege, elevated to decent entertainment by an electric Tommy Lee Jones performance as a deranged government-trained hippie terrorist, and went on to direct Collateral Damage, a piece of post-9/11 paranoia and perhaps Arnold Schwarzenegger’s worst film).

Its simple title isn’t uttered during discussions of the Great American films, and Ford doesn’t strike the same indelible image as a man on the run that he does an intergalactic hero or adventuring archeologist with a hat and whip, but it is enduringly popular. I finally realized on that umpteenth viewing that I’d taken its unadorned, unencumbered professionalism for granted. I knew I liked it; now I started to figure out why. I find the “pedestrian” part of my proclamation to be particularly unfair. It’s a modest, thoroughly mainstream middle-brow movie, yes, but today, as moviegoers are smothered with an endless torrent of computer-spawned apocalyptic action and listless bad guys with end-of-world stratagems, something this intimate, this human, this small-scale is a breath of fresh air 30 years later.

Harrison Ford plays Richard Kimble, a respected vascular surgeon who’s convicted of murdering his wife though he vehemently maintains that a one-armed man did it. (Who would make that up? Besides Special Agent Dale Cooper, that is.) When the subterfuge of less-innocent cons ends in a spectacular freak accident in which the bus is obliterated by a train spewing its ashen whorls and bellowing that horrible horn honk, Kimble escapes and sets out to clear his name.

A classic premise and structure, with a Hitchcockian wrong-man narrative suffused with a Pakula-esque paranoia, the film is presented with that ’90s lighting that actually lets you see what’s going on

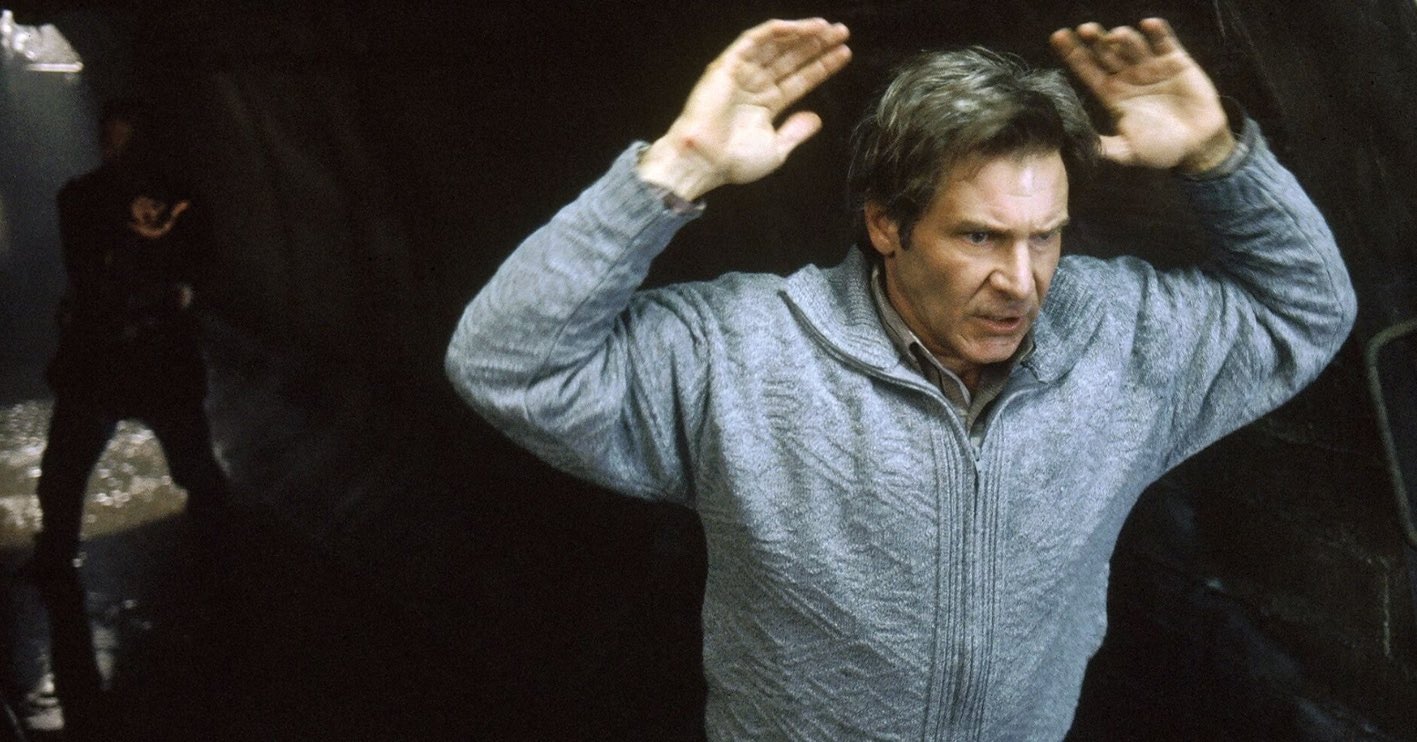

Ford, a speckled-gray swath of beard obscuring his face that is perpetually clenched into a look of barely-contained desperation, a far-cry from the handsome hero’s visage we’re used to, trudges through the dense mess of woods, with the tenacity of true dedication, of innocence, and, using his considerable wits, begins to unravel a terrible tapestry of greed and deadly duplicity, a conspiracy involving doctors and a monstrous pharmaceutical company peddling dangerous pills. Hot on his trail is US Marshal Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones, who won Best Supporting Actor at the Oscars, well deserved), cranky and indefatigable. He doesn’t care if Kimble did it or not—his focus, laser-precise and undeterrable, is to catch his man.

A classic premise and structure, with a Hitchcockian wrong-man narrative suffused with a Pakula-esque paranoia, the film is presented with that ’90s lighting that actually lets you see what’s going on (New Hollywood lensman Michael Chapman knows what he’s doing—he keeps the right parts of a shot in focus, with steady, stable compositions and movements), with the only really bright colors being Gerard’s vermillion scarf and Kimble’s yellow jumpsuit. It’s a prestige picture that spends its decent budget (it cost $44 million, about the same as the previous year’s Patriot Games, and only $20 million less than Jurassic Park) to tell a story, not sell spectacle (though there is that, too).

It’s an exceptionally well-paced film split into clean scenes that accumulate into a prolonged slow-simmer of intrigue and suspense. Being a PG-13 film means a wider audience, more ticket sales; but rather than feel truncated or neutered, The Fugitive makes the rating restriction respectable. It has no need to litter its fine flow of deftly delivered smart dialogue with superfluous curses. There’s little violence, too; Davis doesn’t use gore to sustain the tension rooted in reality. This is—and I don’t mean this derisively—respectable middle-brow entertainment. Davis, Ford, Jones, and the whole cast and crew approach the story seriously, but not overly serious—no grandiose delusions here. It is, assuming suspension of disbelief, not just clever but, as adapted by Die Hard co-writers David Twohy and Jeb Stuart, a smart movie, especially considering its source material: a ’60s TV show of serpentine absurdity.

Another thing about Davis’s movie is that it isn’t aesthetically or formally stylish, and is lacking the potential bravado an auteur, good or bad, might have gone for, with direction more functional than florid. I used to hold that against Davis, but I appreciate it now. It’s sturdy, confident without being ridiculous, which you rarely see today. At the apogee of Spielberg’s popularity, when effects and spectacle were becoming the dominant aspect of mainstream cinema, Davis and co. went small. There’s only one notable set piece in the way we think of it, with old-fashioned analogue awe: when Kimble pulls the guard out of the battered bus right before that inopportunely timed train comes chugging into a fiery crash, metallic shrieking and flames spraying and the hunks of vehicle vestiges chasing Kimble down a dirt hill as he narrowly evades death.

The film has few shots or cuts that still shine in memory: the moments that remain—“I didn’t kill my wife.” “I don’t care.”—are imbued with humanity.

This scene is adroit without being gaudy, and the practical effects have aged splendidly, but the rest of the film has few shots or cuts that still shine in memory: the moments that remain—“I didn’t kill my wife.” “I don’t care.”—are imbued with humanity. There’s a protracted scene in a hospital, featuring a young Julianne Moore, that vibrates with slow, subtle tension as Kimble schemes so slyly to get information on the one-armed man, then saves a boy’s life; Gerard and Cosmo (Joe Pantoliano), always half a step behind, then traipse through the anemic-white halls rife with bodies in distress, coming across a (different) one-armed man, whom they follow to the prosthetics section.

The foot chase down the stone-swoony spiral of stairs in the vast marble splendor of Chicago’s City Hall is also exciting, even though it’s just two middle-aged men running around. Gerard shoots at Kimble, who is saved only by a sliding pane of bullet-proof glass; as Kimble looks at the bullets embedded in the glass, which would have blown his head off, it becomes clear that Gerard is serious. Kimble loses him in the drunken rapture of the city’s raucous St. Patrick’s Day parade, all those staggering drunks topped off with green plastic hats.

In the end, Ford is vindicated, of course, because he’s Harrison Ford and this is a mainstream crowd-pleaser. We never had any doubt. But that doesn’t detract from the satisfaction of reveling in good old-fashioned entertainment. The next time I’m channel surfing and come across The Fugitive, you can be damn sure I’m going to watch it. FL