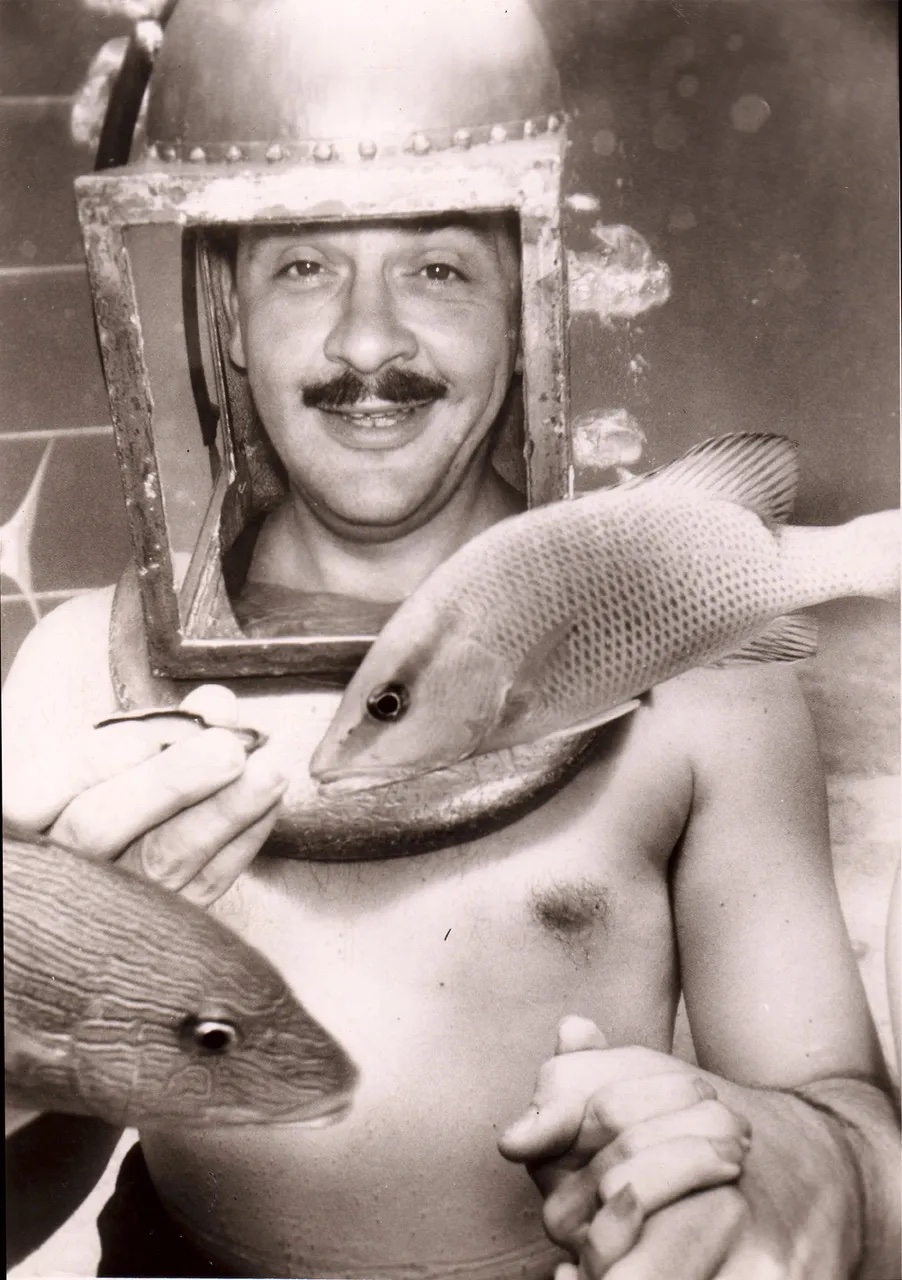

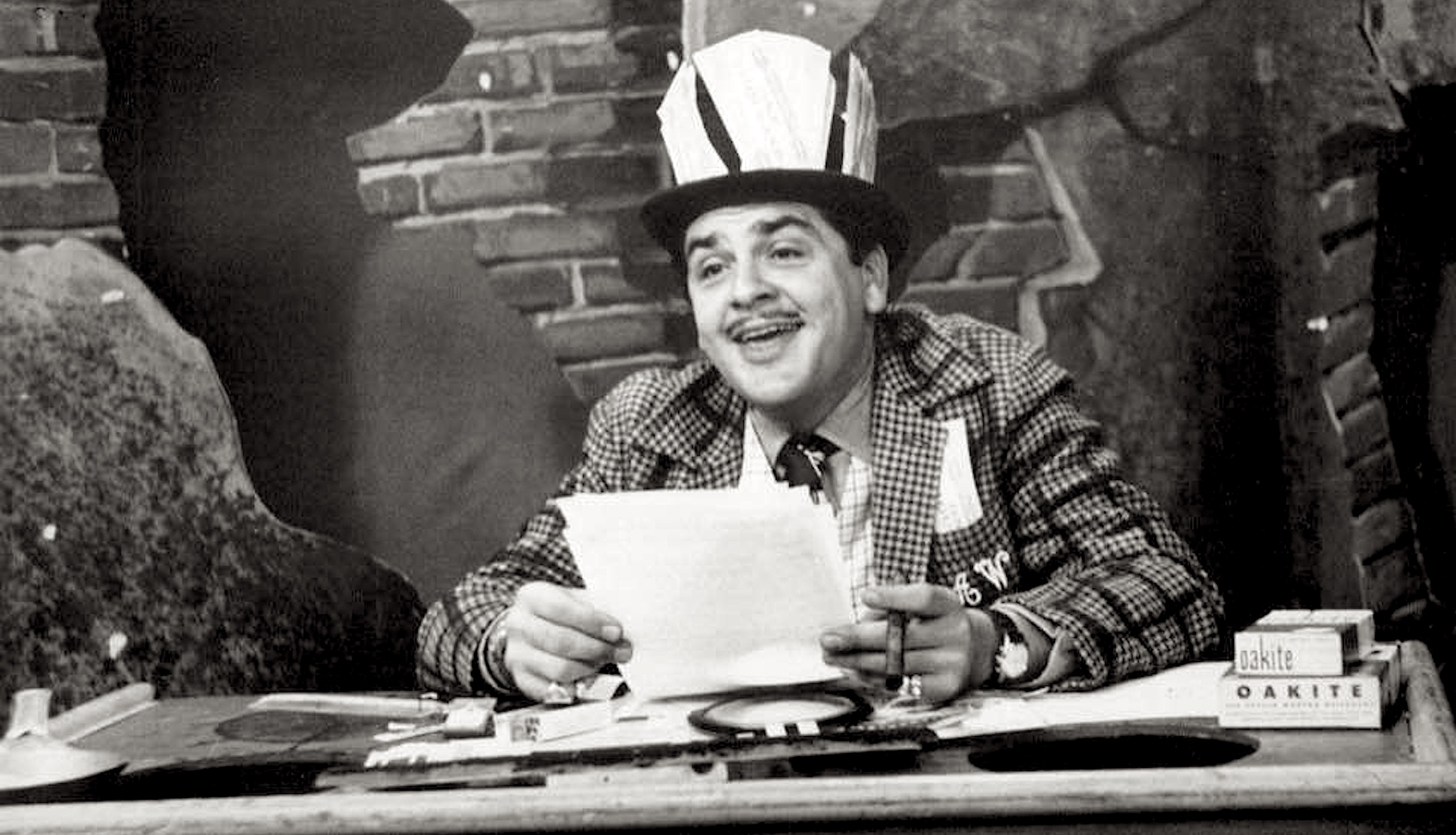

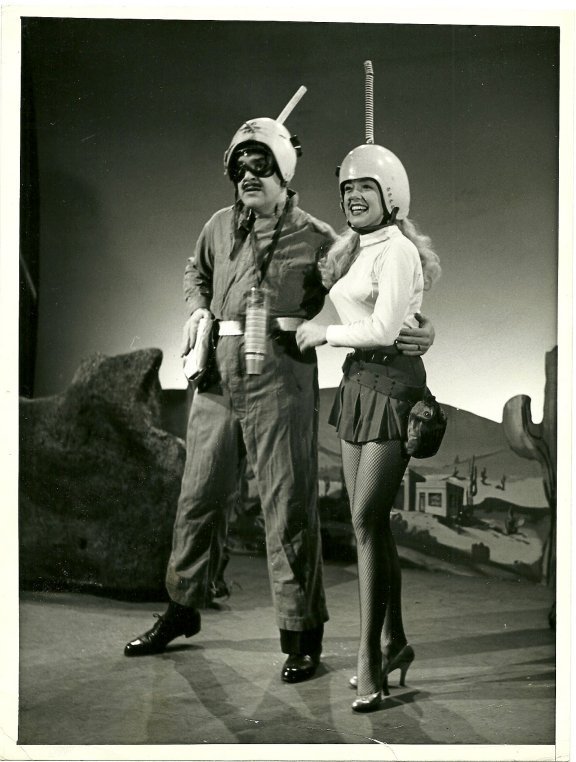

If you could roll every experimental corner of comic (and not-so-comic) video media—from Gary Panter’s look for Pee-wee’s Playhouse, to the frantic kids programming of The Electric Company, to the abstract design of The Residents’ earliest work, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Mystery Science Theater 3000, and SNL—into one flash of light, you’d trace the source of its brilliance all to the early television work of Ernie Kovacs. Pulitzer-winning TV critic William A. Henry III once stated that “Kovacs was more than another wide-eyed, self-ingratiating clown. He was television’s first significant video artist.”

Along with his wife Edie Adams, writer/director/producer Kovacs broke 1950s black-and-white television’s third, fourth, and fifth walls with primitive, effective, improvised electronic design and colorful staging concepts and an avant-garde brand of impromptu humor that would make Ionesco and Beckett green with envy. By 1962, Kovacs had passed suddenly, and the weird mirth of his video artistry would seemingly get lost due to the temporal nature of early TV kinescopes, re-tapings, and lousy storage systems. But comedian/actress Adams and her son, Josh Mills, would never let the as-yet-untested world of fast multimedia forget its roots in everything Kovacs.

Along with making it the stuff of exhibited, curated museum fare—available to researchers at the University of California and the Paley Center for Media—Mills himself became a one-stop shop of Kovacs (and Adams) expertise and salesmanship, editing and selling the mayhem of the marrieds to networks such as Comedy Central, then on DVD and Blu-ray to Shout! Factory. Mills’ Ernie & Edie store alone is a wealth of comic invention that must not be ignored, whether you’re a performer, writer, or burgeoning DIY director.

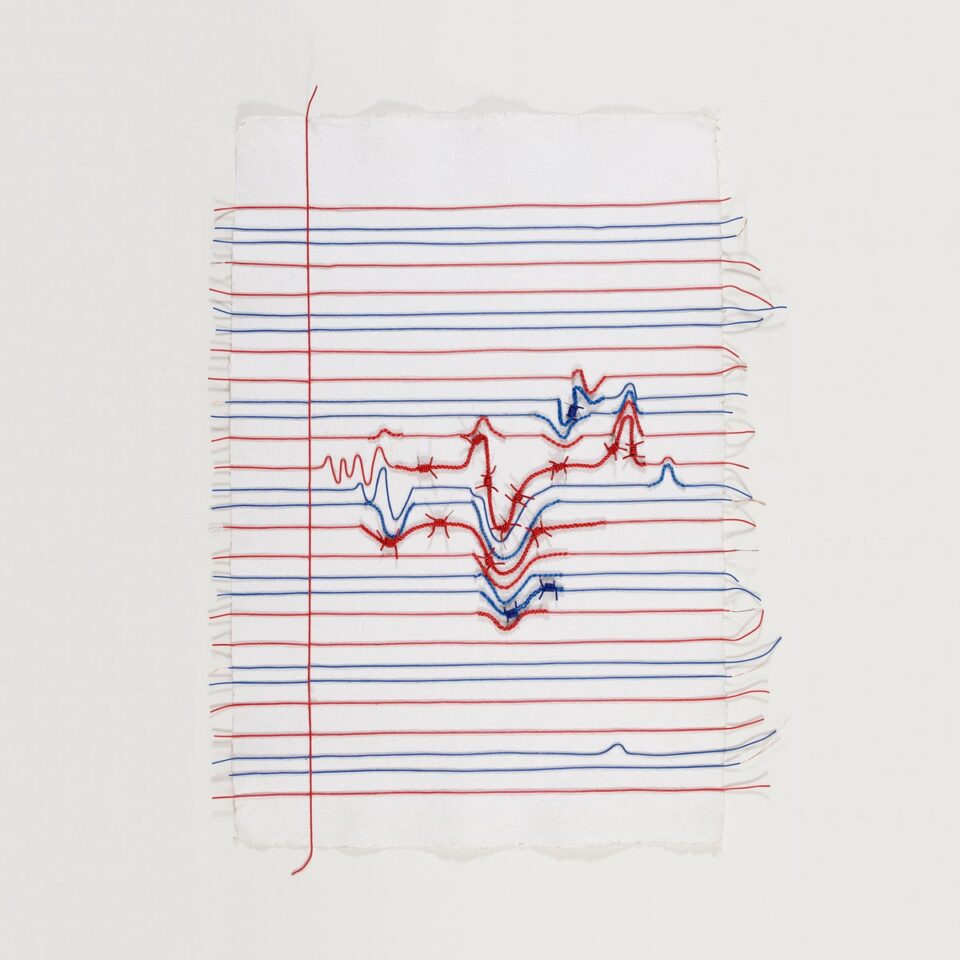

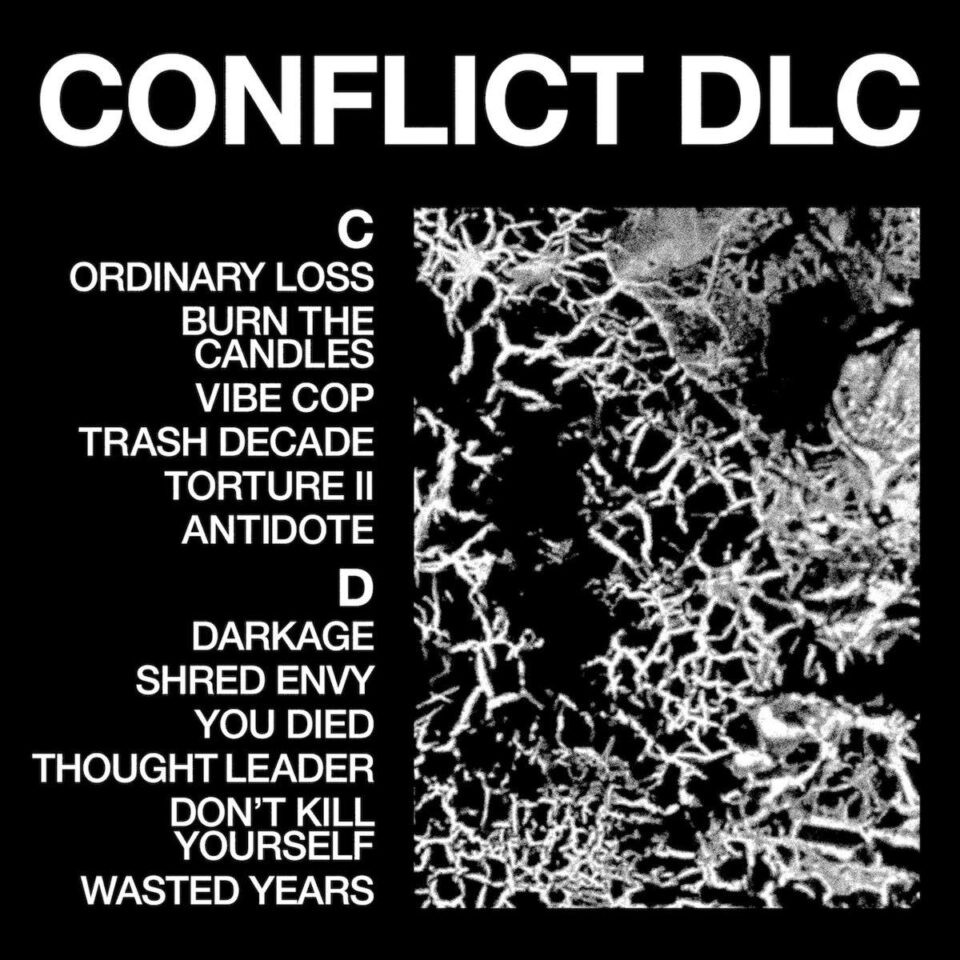

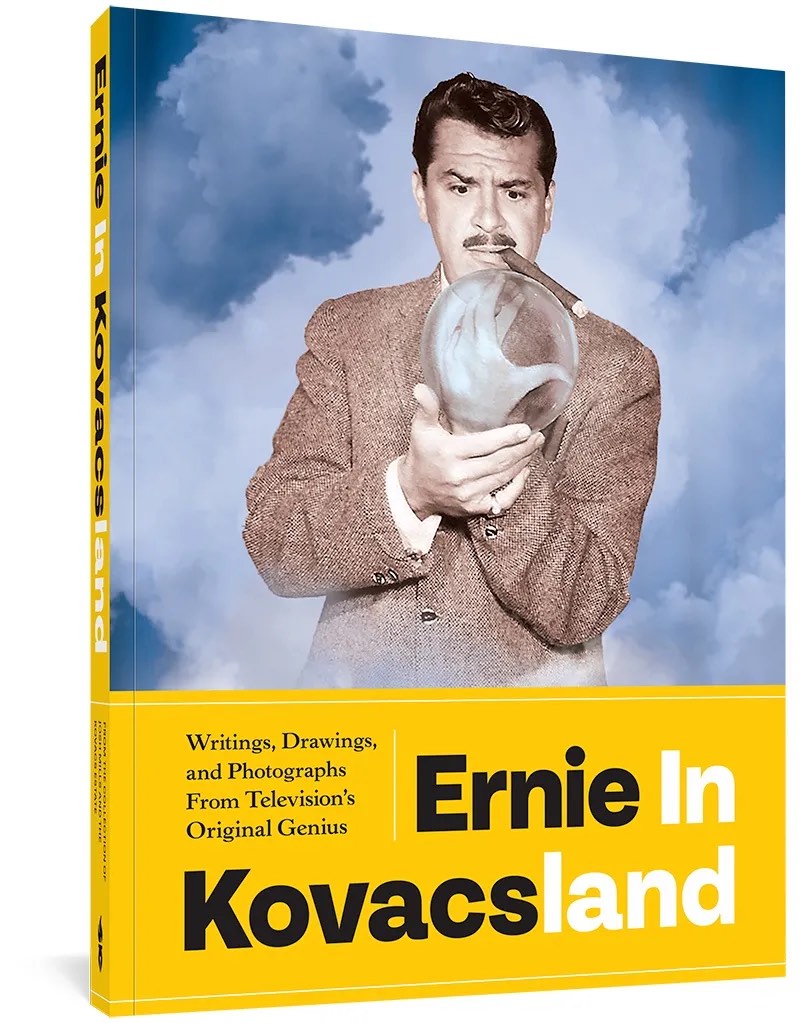

Now, Mills is off to new adventures in Kovacs-land. Shortly after a recent evening at the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s Billy Wilder Theater for a screening and conversation event, Mills released his new book (with co-author Pat Thomas and a forward writer Ann Magnuson) Ernie in Kovacsland: Writings, Drawings, and Photographs from Television's Original Genius through Fantagraphics. We sat down with Mills ahead of its release in late July to discuss all things Kovacs.

Your wealth of knowledge about and dedication to all things Ernie Kovacs runs so deep that I always forget he’s not your blood father. Can you discuss why this adoration is so enduring?

It’s my mom. She worked so hard for so many years preserving the physical legacy of Ernie Kovacs and keeping his name alive via that preservation that there was no way I could just decide not to do it. I’m trying to keep my mom’s legacy alive, too—she preserved that as well. She saved her own and Kovacs’ audio and video archive from being taped over, erased, dumped in the Hudson River, so I had to try and keep this going. Plus, Ernie is really funny.

Can you recall the first time your mom ever revealed the secrets of his particular genius?

I have a memory of watching one of Kovacs’ most famous gags, The Nairobi Trio, as a pretty young kid. I found it a little macabre and surreal, even though I didn’t know the words at the time. He was omnipresent in our house—photos on the walls with my mom, Ernie on the cover of TV Guide, his Emmy, his scripts, his archive, and his den just off the house were things I saw everyday. He was physically there in many ways. I thought all kids grew up like this—with a bearskin rug and dueling pistols hanging around. I was so ingrained in this thinking that I was convinced that The Addams Family was based on our family. Gomez [John Astin] looked like Ernie. Our house looked like their house. It made sense. I think I realized then that maybe there was more to it than just a skit. That what he was doing was different. It seemed like it all sprang from Ernie. Even my TV watching habits.

“I thought all kids grew up like this—with a bearskin rug and dueling pistols hanging around. I was convinced that The Addams Family was based on our family.”

What do you know now about Kovacs that you didn’t know when you started this book?

I learn new things all the time looking through the archive—which was a huge reason I wanted to do the book. I thought it was a shame that no one else got to see cool stuff like how he wanted his records to be placed on the shelves, or a dirty joke book given to him by Sid Caesar, or even seeing what the budget was for The Tonight Show when he hosted. I run across things all the time and just marvel at what he did and how my mom saved it all these years. This all exists in 2023. That’s amazing to me.

What do you believe Ernie and Edie offer to the kid on TikTok, the burgeoning filmmaker, the Gen Z person who chooses to rail against the patriarchy, the matriarchy, and everything else?

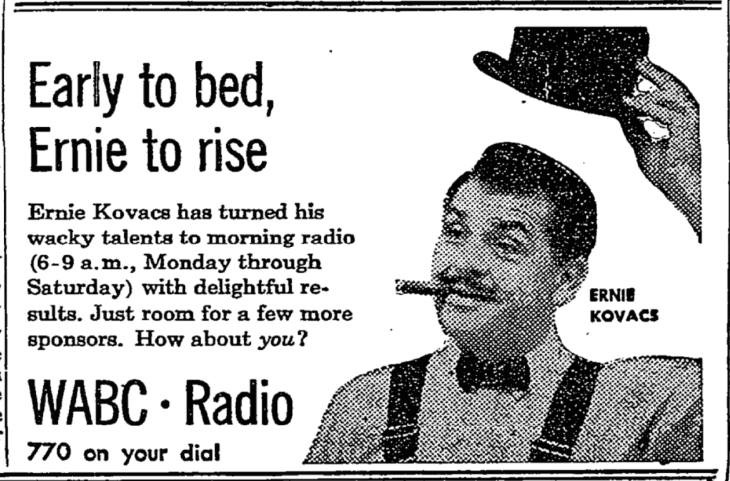

Ernie didn’t like authority. At all. He hated to be told what to do. He had a vision, and no one would tell him what was funny and what wasn’t. So he often clashed with executives. Kovacs was never a huge ratings guy, but he always worked. As fast as one network would hire him for a morning show, he’d be off the air and another network wanted him for a late-night show. So you really had to search out Ernie Kovacs on television—or even radio.

“Ernie didn’t like authority. At all. He hated to be told what to do. He had a vision, and no one would tell him what was funny and what wasn’t.”

So I think that secret of finding Ernie on CBS one day and ABC on another made him special to his fans. He always got terrific press, and the networks wanted that as much as they did ratings. I think for people today with 8,000 choices for entertainment, Ernie appeals to the quiet, slightly offbeat person at the party who couldn’t do a party trick to save his life and impress the room, but he was the guy that could wow you in a one-on-one conversation about any subject. If subtle, thinking, offbeat humor is your thing…Ernie is your guy.

Considering that we’re knee-deep in a writers’ strike and an actors’ strike, what would Ernie have said?

When Ernie was brought out to Hollywood by tough-as-nails Columbia Pictures mogul Harry Cohn, evidently their first conversation went something like this: “So, you’re the offbeat, weirdo New York comic everyone tells me is so funny that I had to pay a king’s ransom just to be in our movie?” To which Ernie said, “And you’re the fat, bald-headed guy who runs this second-rate studio, huh?” Cohn laughed. No one talked to Harry Cohn like that. They were great friends after that. But he didn’t take shit from anyone—even if they were paying the bills. Ernie often bit the hand that fed him. And usually won.

I know that he story-boarded so much of his work—how scripted/drawn was it versus improvised?

It depends on what era. In working on Ernie in Kovacsland there was very little Kovacs left to chance. He even sketched out where his jazz records needed to be in his collection. However there was a time when Ernie was doing both television and radio five days a week. He simply couldn’t come up with enough material for 10 hours of entertainment a week. Which is why he often said, “The best stuff I come up with is 15 minutes before I go on air.” He had to improvise just to get through each show. He hated writers. Not the person, but the job of a writer. He wanted to conceive, write, direct, and produce everything he did. So I would say when he could focus, he was very scripted—his own script. But if he was busy, much of it had to be improvised. That’s a talent.

“We could do another five or more books just on Ernie and they would be just as illuminating. And that’s not counting a book identical to this on my mom as well.”

You’ve published and produced so much written and visual work on Edie and Ernie in the past. What’s the rarest item in Kovacsland?

We tried to put things in there that people might have heard about but never knew existed. For instance, there was a rumored novel he was writing when he died called “Mildred Szabo.” It had never been seen before. We found the 10 or so pages that exist and added it in the book. I’d never seen it, so I know no one else had, besides a few people in the inner circle. Honestly, we could do another five or more books just on Ernie and they would be just as illuminating. And that’s not counting a book identical to this on my mom as well.

Pretend I just fell to Earth and have no idea who Ernie Kovacs or Edie Adams are, or what they did—give me the nickel ride through their necessity.

Ernie was the hippest guy in the room, as Ann Magnuson said in her [foreword]. And my mom was a Juilliard-trained singer who was a Tony winner herself. They were not a comedy team à la Burns and Allen, or even Jake and Elwood. But they were a creative team that were about as dynamic—and different—from anyone in Hollywood or New York that they really were at the apex of their creative and celebrity prowess at the very same time. And both of them were good, honest, funny people. That’s hard to come by. FL