There’s a scene in Before Sunrise, Richard Linklater’s 1995 movie about young romantics exploring Vienna on a whim together, in which Ethan Hawke’s character Jesse recites part of a poem to Julie Delpy’s Celine. The poem is W.H. Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening,” but Jesse imitates two verses from a version he owns, which is a live performance by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. It’s (knowingly) pretentious and romantic and beautiful—Celine lying in Jesse’s arms in the empty early morning as their single night together draws to an end, the poem unfolding first in the space between them, and then the barren city that surrounds them:

All the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.

In headaches and in worry

Vaguely life leaks away,

And Time will have his fancy

To-morrow or to-day.

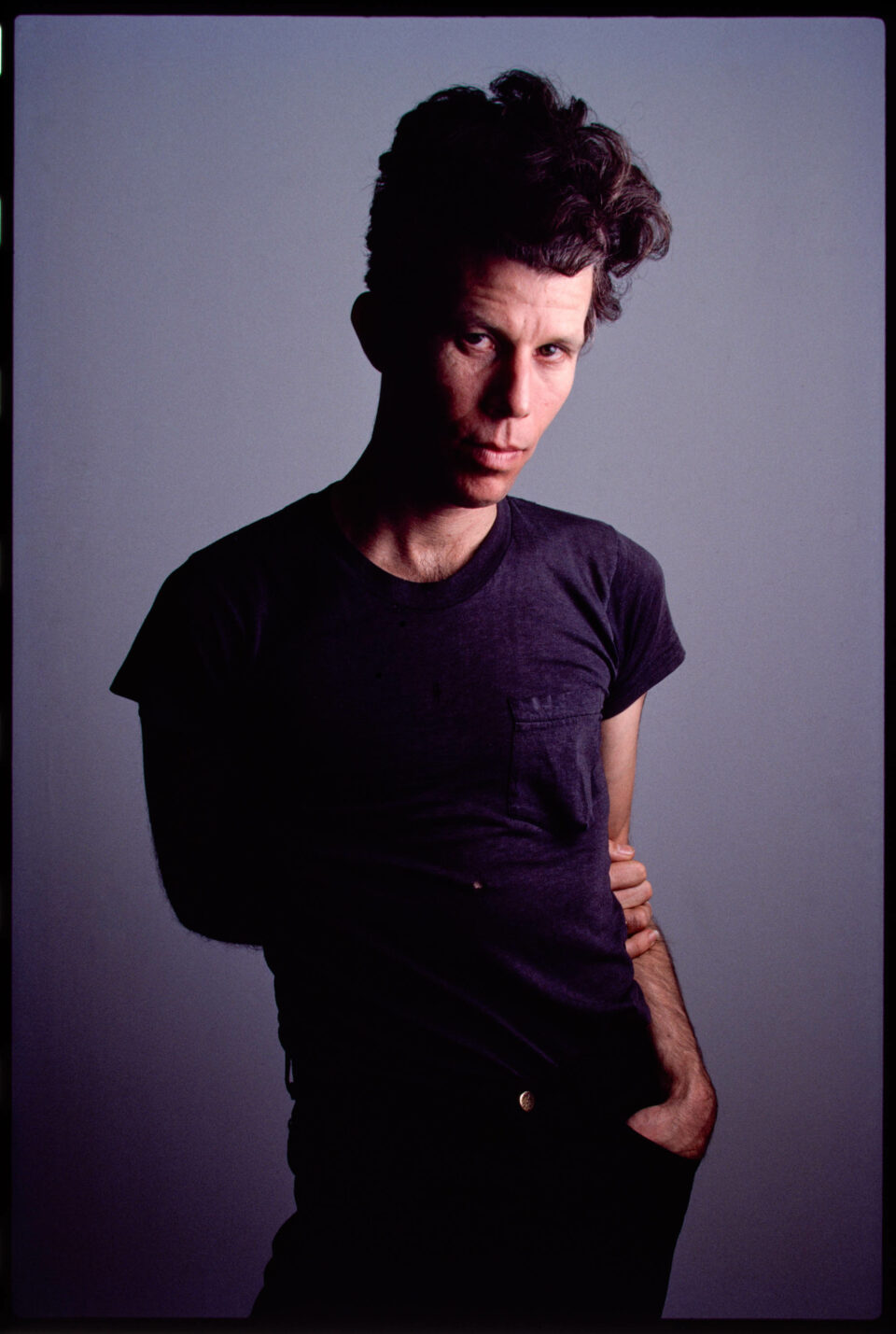

It could, in some parallel dimension, be a Tom Waits song. After all, Jesse’s impression of Auden isn’t too far off from Waits’ distinctive growl, and the poem’s subject matter—the running down of the clock and the mortality that we all face as humans—crops up often in Waits’ songs through the wounded (anti-)heroes they’re home to, who proudly prowl the underbelly of society. In fact, listening to Tom Waits—especially the three ’80s records (1983’s Swordfishtrombones, 1985’s Rain Dogs, and 1987’s Franks Wild Years) that have just been reissued—you’re drawn deep into the lives of the characters that populate the world he creates, many of whom are succumbing—as we all are—to the whims of time, their lives fading like their dreams, their hopes.

They are, in some ways, the real people in movies that you never see, even though they’re mostly figments of Waits’ imagination—characters that are larger than life designed to remind us how small we are and how, whoever and wherever we are, we’re all just sacks of bones and flesh, trapped by our mortality and gently decaying with every second, utterly insignificant, despite how our problems may make us otherwise feel. Take, for instance, the waitress or bartender who has her moment to shine in the spoken word track “9th & Hennepin” on Rain Dogs—but she shines only to rust:

They all started out with bad directions

And the girl behind the counter has a tattooed tear

One for every year he's away she said, such

A crumbling beauty, but there's

Nothing wrong with her that

$100 won't fix, she has that razor sadness

That only gets worse

With the clang and the thunder of the

Southern Pacific going by

As the clock ticks out like a dripping faucet

’Til you're full of rag water and bitters and blue ruin

And you spill out

Over the side to anyone who’ll listen…

And yet, at the same time, Waits likes to fuck with time. Indeed, his songs have always had a timeless quality. They’re so crucially, unmistakable him that they’re not rooted to the era in which they were made, nor the time in which their characters exists, but drawing deeply from a distant past as well as an unforeseen future—that parallel dimension in which that Auden poem read by Thomas read by Jesse exists, layers of existence and time slathered on top of each other, that past and future fighting for dominance but always in a state of perpetual entanglement. These three albums were, to some extent, the start of that, where he transitioned from the down-and-outcast of his early work—the forlorn, drunken, wistful, wounded, late-night jazz/lounge bar romanticism of “Martha” or “Tom Traubert’s Blues”—to a more iconoclastic, experimental musician and songwriter, leaning into his eccentricities and changing the course of his career as a result.

Waits’ characters are the real people in movies that you never see—characters that are larger than life designed to remind us how small we are.

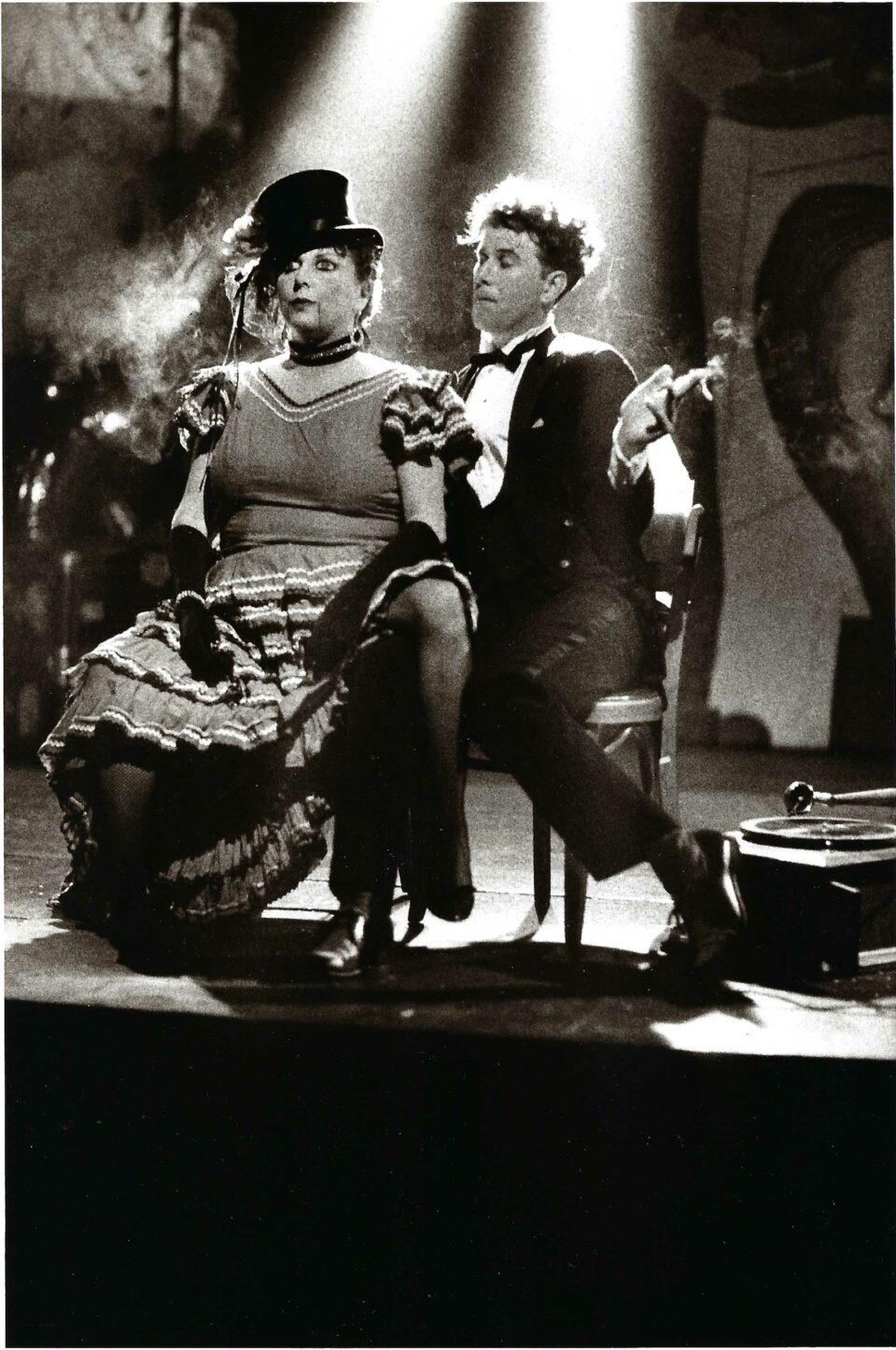

Not that those melancholy, maudlin characters disappeared. Rather, they just lurked more in the periphery, hiding in the shadows and sucking on cigarettes as they became more abstract, less human—though ironically capturing the existential crises of the human condition to an even greater level—as Waits dismantled the notion of time more than ever before. On Franks Wild Years (named for a song on Swordfishtrombones and whose songs were written for a play of the same name), “I’ll Be Gone” both transcends and makes a mockery of time in its first verse (“Tonight I’ll shave the mountain / I’ll cut the hearts from pharaohs”) while its chorus repeats and insists the phrase “And in the morning I’ll be gone.”

It’s surely no mistake or coincidence that this song is followed by “Yesterday Is Here,” whose key phrase, “Today is gray skies, tomorrow’s tears / You’ll have to wait ’til yesterday is here,” disrupts the notion of time even further. And yet, even though it makes no sense on paper, when you hear it and feel it, its meaning couldn’t be clearer. (Similarly, “Way Down in the Hole,” from the same album, is a song from the point of view of a “berserk evangelist.” It’s a stunning song in its own right, but it wasn’t actually included in the play itself, so on the album it’s almost as if Waits himself is the fucked up preacher rather than the character who’s meant to be singing the song).

Of course, the here and now still exists on these albums, too. Perhaps the best example of that is Rain Dogs’ “Downtown Train,” a beautiful rumination on love and youth and the transience of both. It shimmers and shines like the yellow moon and new dime of its first verse, after-hours hopes and dreams flickering like faulty subway lights as they plunge through the drunken night with memories of the past and the hopes to revive it in some distant future. Deep beneath the subway system, however, is the world of Swordfishtrombones’ opener “Underground.” A dark, mysterious, and peculiar subterranean location that’s straight out of Waits’ imagination, it sounds like a goblin chain gang at work, and truly extends the distance between the unreal and the real that exists across these three records—indeed, all three albums feel connected and aligned—composite parts of the same whole.

Beyond that, they also exist in the real world, both in the here and now in their newly glorious remastered form—courtesy of Chris Bellman and Bernie Grundman Mastering and Waits’ longtime audio engineer, Karl Derfler—but also in the past, in memories brought once again to life. For me, there are two in particular that get resurrected frequently. The first is how my dad bought me Franks Wild Years on CD from a second-hand record store in a small town called Hythe in the UK when I was only 11 or 12. It terrified the hell out of me when I first heard it and it took courage, a few years later, to attempt listening to it again. That second time, I fell in love with Tom Waits. I love every era of Waits’ music, but Franks Wild Years remains my favorite record, and every time I listen to it, I remember viscerally the shock of hearing it for the very first time, of never wanting to listen to it again, of thinking I would never, ever like it.

Franks Wild Years remains my favorite record, and every time I listen to it, I remember viscerally the shock of hearing it for the very first time.

And then there’s the converse: trying to convince my dear friend that the original version of “Downtown Train” was infinitely better than Rod Stewart’s cover. It took him a while to come round, but he eventually did. And though I lose myself in the emotion of that song and my own memories of New York City when I listen to it, I’ll also never not think of the arguments about it. It’s another, perhaps more meta, example of Waits bending time, but as these records—which are re-released 40 years to the day that Swordfishtrombones came out—show, he’s one of few artists who can really sculpt it into its own distinct entity, who can make time his own. Now 73, he certainly won’t be able to conquer it, but his music, and these albums in particular, absolutely have. FL

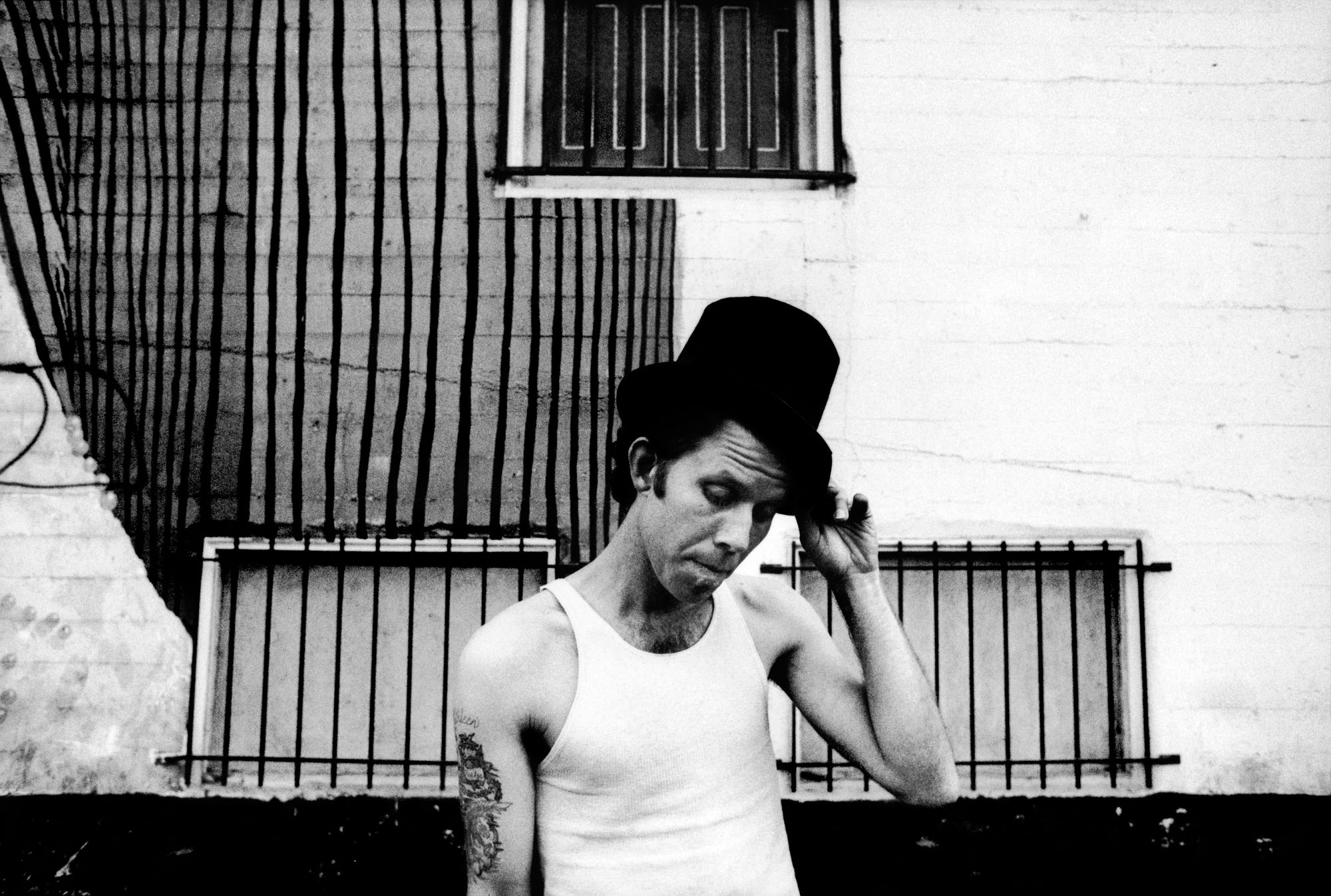

Photo by Michael O’Brien in 1983