Whenever lists of “greatest concert films” are compiled, Stop Making Sense usually ends up at the top. Directed by Jonathan Demme, the 1984 film captured Talking Heads at the peak of their powers during four nights in December 1983 at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater.

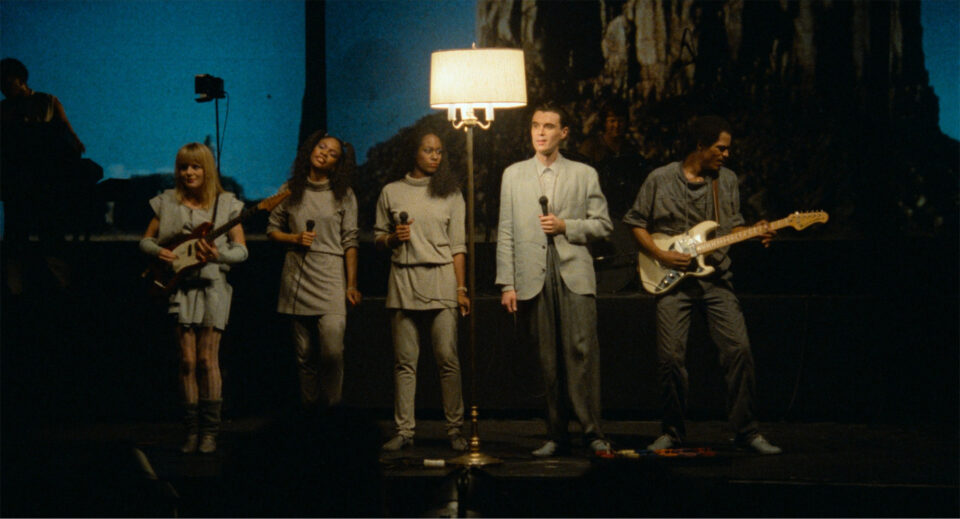

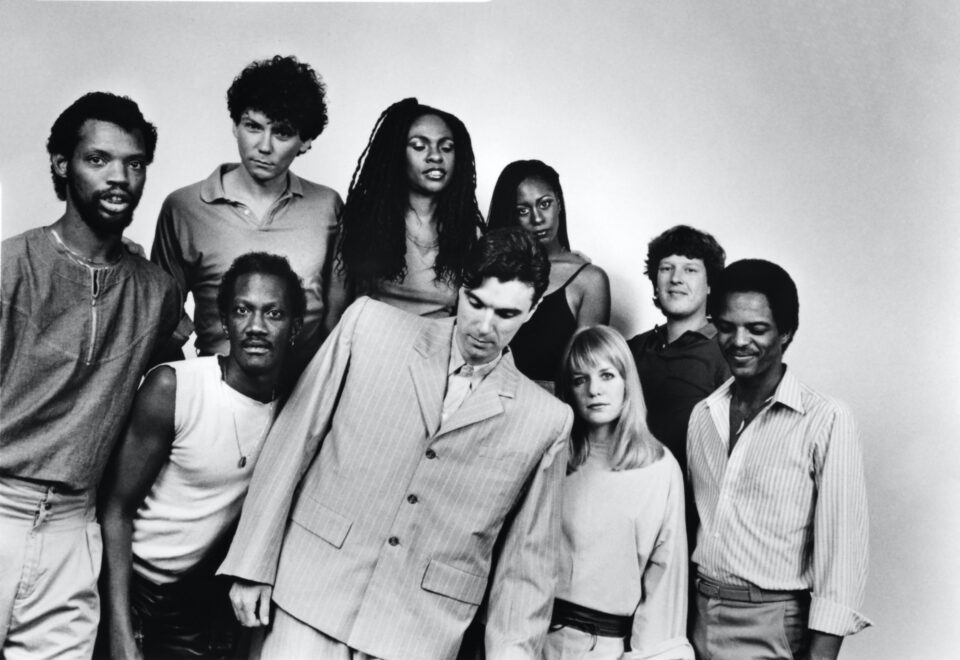

The presentation of the film is simple: For nearly 90 minutes, the core of the band—frontman David Byrne, guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison, bassist Tina Weymouth, and drummer Chris Frantz—plays a joyful, danceable, and career-spanning set of songs abetted by P-Funk keyboardist Bernie Worrell, Brothers Johnson guitarist Alex Weir, percussionist Steve Scales, and backing vocalists Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt. There are relatively few audience shots, no interviews or backstage antics, and—with the exception of the Noh-inspired “big suit” that Byrne dons late in the film—no visual gimmicks.

As a result, Stop Making Sense connected immediately with both diehard Talking Heads fans and those largely unfamiliar with the band who could appreciate a concert film that was driven by music instead of spectacle. A critical and commercial success at the time of its release, the film has since been selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, and its soundtrack has sold over two million copies.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the concerts filmed for Stop Making Sense, a newly restored 4K version of the film will return to theaters later this year for a global theatrical run. Rhino has also released a deluxe version of the soundtrack which includes the complete concert for the first time; both the soundtrack and film now include two previously unreleased songs—“Cities” and the medley of “Big Business/I Zimbra” from the concerts—as well as a new Dolby Atmos mix overseen by Jerry Harrison and Eric “E.T.” Thorngren, who also mixed the original release.

We spoke with Harrison about Stop Making Sense and its legacy, as well as the buzzed-about upcoming “reunion” of the four Talking Heads members, which takes place today at the Toronto International Film Festival. Read more about the event here, and find our full interview with Harrison below.

What’s it been like for you to not only watch Stop Making Sense again after all these years, but to also remix the music?

It’s been fantastic. I worked on the Atmos mixes of all of the [Talking Heads] studio albums, but this one was interesting because the mixes for those albums were generally for headphones, whereas we knew that this was going to be in theaters as well. When we were doing the mix for the film, it was like, “Let’s respond to what’s on the screen”—so if it was a shot of Alex Weir doing something on his guitar or something like that, we’d bump it up a little bit so the visual cues were being acknowledged by audio cues. When people go to see it in the theater, there are now so many channels and so many different speakers, you have more ability to go, “What’s Bernie playing on this?” It’s easier to try to pick apart what’s going on, which I think will make it even more fun to see the film more than once.

“This was the time of the cult-like status of The Rocky Horror Picture Show... I always wanted Stop Making Sense to break into that scene, and we succeeded at it becoming something like that.”

Did watching it bring back a lot of memories from the filming?

Very much, and it also made me fall in love—maybe with this level of detachment from years later—with the brilliance of each of my bandmates. I’ve said it a million times about how Chris has just this great groove. I have this thing that it’s not always just about how steady a drummer is; if you believe in their beat enough, then you abandon trying to establish the beat yourself, and you flow with that beat. If you feel uneasy about the person or the device, whatever it is that’s doing it, then you maybe fight it or try to influence it a little bit. So just things like that, and details like a place where David does a yelp in the middle of something, and it’s just like, “Oh, that was unexpected and so cool!”

Watching the film again, I was struck by just how tight and funky you were as a core unit. What do you recall about Talking Heads’ journey to funk?

When we released Talking Heads ’77, I think there was this mystery of, “Wow, this is just unusual, what are their influences?” And when we put out More Songs About Buildings and Food and included “Take Me to the River,” it was like, “Oh, it’s R&B!” We’d always been really influenced by R&B, which then of course became funk; and then we expanded to African music, and Fela [Kuti] in particular, who’d been very influenced by James Brown. So all along, that was something we gravitated toward.

1984: The Talking Heads line-up for the concert film ‘Stop Making Sense’ (L-R Steve Scales, Bernie Worrell, Jerry Harrison, Ednah Holt, David Byrne, Lynn Mabry, Tina Wemouth, Chris Frantz and Alex Weir) pose for a portrait in 1984. (Photo by Sire Records/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Talking Heads actually financed the original film, correct?

We co-financed it with Warner Brothers.

Were you forced to do that because Warner Bros considered the project a risk? Or was that a way for you to have as much control as possible over it?

We always wanted to have control of things that we did. I mean, we were a very efficient and cost-effective band, because we didn’t want to get into the position that we owed the record company money; we knew that once we did that, we’d then suddenly be asked to do things that we didn’t wanna do. And we felt that we intuitively had the best sense of what were the right decisions for us, particularly in the earliest days. Fortunately, with Sire, I think Seymour [Stein] saw in the very beginning that it was a band, and it was better that he get out of the way. If he had something he was gonna say, he would say it; but still, that was our attitude.

“We were so individually ‘the Talking Heads’ that the music doesn’t feel dated in some particular way. Which is, I think, why the music continues to be played.”

So when we came to this film project, there was a sense of wanting it to be with people that we trusted and knew. And of course, as it worked out, it was distributed by Island Alive, which was Chris Blackwell. And we knew him from Compass Point [Studios], and Tom Tom Club were on Island, and [Talking Heads manager] Gary Kurfirst had a long, long relationship with Chris. So there was a sense that if we really hated something, we could get to Chris personally and complain; certainly Gary could.

And Warner Brothers Records being the co-financiers rather than the film company, it was people we knew and had a relationship with, as well. I think that they didn’t necessarily want a film company coming in and messing up things for selling records. It was like, if we keep the financing in-house, or with people that are already working together, we won’t run into conflicts of interest, and we can also coordinate the film with audio releases and things like that.

Did you have any idea that the film would be such a critical and commercial hit?

I don’t think anyone had any idea, certainly in the beginning, that the film would end up having the success it did. This was the time of the cult-like status of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which was playing in theaters every weekend at midnight, and people were coming to see it over and over again ’cause it was such a fun date, so to speak. I always wanted Stop Making Sense to break into that scene, and we succeeded at it becoming something like that. And because it’s a film that doesn’t have any interviews, it’s just the concert, it’s not like, “I have to wait around and listen to this interview before I can dance.” You can get into it for the whole thing.

Which is why it’s aged so well.

I also think, to a degree, that the lighting effects that David chose when building this show were all things that really could have been done in, like, 1930. We didn’t use things like Vari-Lites, which had just come out; so, other than our clothes, it doesn’t feel dated to a particular time period. And though the mixes of certain albums really do reflect the time period—the volume of the drums got louder and louder in the ’80s and ’90s, and the drums got more present in our mixes, too—we were so individually “the Talking Heads” that the music doesn’t feel dated in some particular way. Which is, I think, why the music continues to be played.

There’s been a lot of buzz about the four of you reuniting in Toronto for the debut screening. Should we be reading anything more into this?

Well, it is going to be the first time of us all being on stage since…there was a reunion around the time of the re-release of Stop Making Sense in 1999 that we did at the San Francisco Film Festival. And then, of course, we were together at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002. But since then, this will be the first time that we’re all sort of present at the same time. I don’t think that this is us saying, “OK, we’re all going on tour next week,” or something like that. But I do think it’s a great thing. I think we’re all very proud of what we did with Stop Making Sense, and we’re just delighted that it’s getting this attention again—and that it’s getting, you might say, an update.

“I think we’re all very proud of what we did with Stop Making Sense, and we’re just delighted that it’s getting this attention again.”

And really, we’re hoping for it to gain a new audience, as well as satisfy the old audience that’s been there the whole time. I’ve been doing this tour with Adrian Belew, and the kind of shows that I enjoy the most are where we have a mixed stage audience, where I can see that people who’ve been following Adrian and me and Talking Heads for decades, and then there’s people that are younger—sometimes maybe the kids of some of those people, but it’s another audience entirely. And just seeing that whole all-ages group having a great time together is really terrific.

So I think that’s the hope here; and I think that’s something all of us completely agree on. It’s no secret that there’s been some friction at times in the band, but my general feeling is that people have already said whatever things needed to be said. So now, let’s celebrate what we did together and move forward. FL