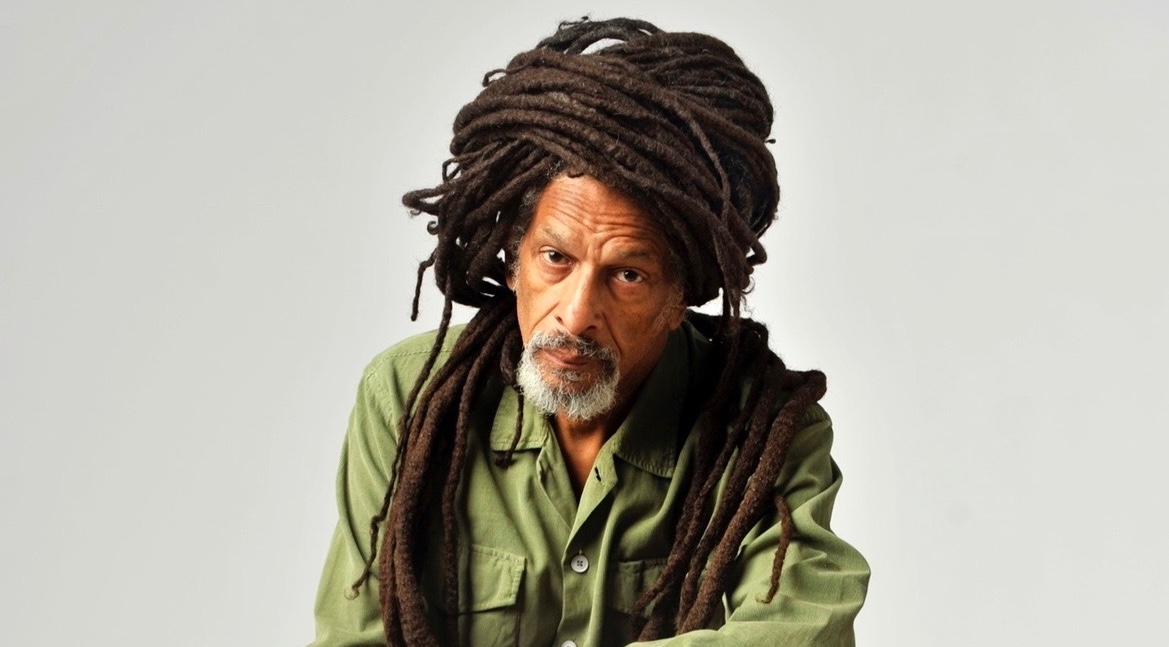

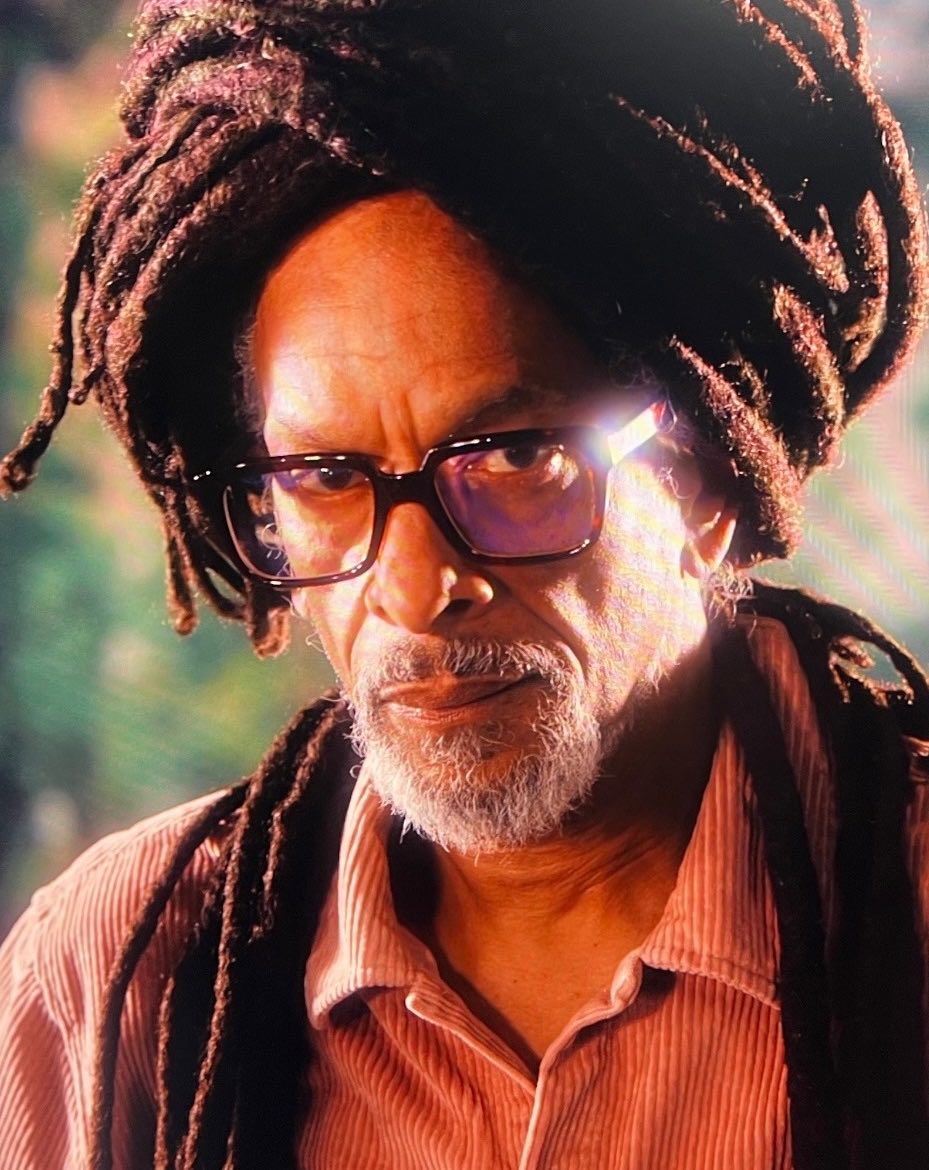

The release of Outta Sync this week may signal the full-album debut of London-born artist Don Letts, but the 67-year-old has been part of Britain’s musical fabric since the mid-’70s when he ran a London clothier that supplied fashion to the elite of the burgeoning punk scene—including members of The Clash, with whom he cinematically made his bones, and as a creative with Mick Jones’ Big Audio Dynamite outfit.

There were a million jobs in between that clothing shop and his familial relationship with The Clash (DJ, party promoter, Slits manager), with Letts always making the most out of being a man of style and taste whose focus centered on all things dub and dancehall. There were a million jobs after BAD, with more music videos and documentaries to be directed, art to be made, autobiographies to be written—even plants to plant, as his green thumb became renowned via the BBC’s Gardeners’ World.

Creating jobs for himself is what Letts has always done, acting as a self-starting, self-stylized ideas man. Why not do an album such as Outta Sync, surprisingly topped as much by pop as it is the punky reggae party of his youth with new guests and old friends such as producer Youth and the late, great Terry Hall from The Specials adding to the positive vibe and its pragmatic, ancient-conscious lyrics?

We spoke with the punk icon from London about his, well, don’t call it a career. Call it a lifetime.

You once told The Guardian that “a good idea attempted is better than a bad idea perfected.”

Yeah, I’ll stand by that quote.

How does that pertain to everything you’ve made—from films through to the new album?

I would say that we need to cite the things I’ve done and how I’ve done them. For instance, my very first film—my so-called film The Punk Rock Movie—was never intended to be a film. I was filming bands who’d just turn up on my Super 8 movie camera. Next thing, I read that I was making a punk-rock movie. Good idea. I’ll call it a film. Even calling that a film is a stretch. It documented a period, and its content overrode its technical faults.

Everything I did with Big Audio Dynamite might be another example. The ideas I contributed to that band were based on the fact that I couldn’t play anything. But because I can’t play anything, my ideas come from places other than music. My first entry into the band was me doing that sample and dialogue thing until I quickly realized that you don’t get paid for stealing other people’s shit, so I pushed myself into lyric writing. An Orson Welles quote springs to mind here: “If you want to make an original movie, don’t watch films.”

So, when you ask me about attempting something, to me it’s never about perfection, it’s about the idea. There’s a lot of perfection about in the 21st century, and so much of that doesn’t emotionally connect with me. I like the mistakes, that’s where the magic is. The advances of the digital age are to creativity’s detriment.

“There’s a lot of perfection about in the 21st century, and so much of that doesn’t emotionally connect with me. I like the mistakes, that’s where the magic is.”

So the “happy accident” in your life as a creative has great weight.

That’s an oversimplification, as you also have to put some taste in there. Your radar has to be receptive to the right ingredients. I don’t believe in luck, by chance. I believe you create your own luck by the choices you make. I never had any plans or goals other than I didn’t want to be broke. I spent my whole life just chasing the creative buzz in whatever medium I’m presented with or can afford at the time. My only discernible talent is that I have great taste, which, in this century, is some remarkable fucking currency.

Jamaican music and culture had forever been a part of Great Britain, but you turned a lot of young punks onto the whole Rastafari culture, and that of underground reggae and dub. What was your first turn on?

That’s easy. The thing that made my ears prick up was a track by Lee “Scratch” Perry, the B-side of his “Clint Eastwood” single called “Tackro” in 1968, which featured an early idea of what we now know as dub. It was so different than anything out there—reggae-wise, globally. After that, it was a hop and a skip to things like King Tubby Meets the Rockers Uptown and Keith Hudson’s Pick a Dub.

photo by Josh Hight/Cutler & Gross

It was dub that created my lifelong love of bass culture in Jamaican music. So yes, I used my culture to turn white people on, but, there’s also the duality of me being Black and British to consider. I was digging The Beatles and The Stones as a kid. The first live band I ever saw was The Who. That was truly the band that opened the door to Don Letts being who is he today—the fucking Who. I saw them when I was 15 years old in 1971 in a full production rehearsal. I was 15 feet from the stage and could see the whites of Keth Moon’s eyes. They’re in my life forever.

If I’m being honest, I’ve never been happy being defined by my color. Jimmy Page’s guitar riffs struck a chord with me, and my Led Zeppelin II album sat alongside my Big Youth Dreadlocks Dread record, proudly.

Was that an easy trip, your attempts to open people’s minds and taste?

I’ve never tried to open anyone’s mind. I do my thing, and sometimes it resonates. I’m not a teacher. I don’t have any messages for anybody. In hindsight, I believe that I led by example, at best. But there was never a game plan. That sounds selfish, but yes, my journey has been a selfish one.

Or at least one that satisfies you, first.

If you like it all, cool. If not, we’re speaking a different language—that’s always been my thing. Even with my kids, I don’t try to ram anything down their throats. What comes to mind is a conversation I had with Bob Marley where he was making fun of me for my punk-rock clothes, my bondage trousers. I stood my ground and told him he was wrong. A few months later, the brother released a song, “Punky Reggae Party.”

“I spent my whole life chasing the creative buzz in whatever medium I can afford at the time. My only discernible talent is that I have great taste, which, in this century, is some remarkable fucking currency.”

What is your recall of your first musical escapade, 1978’s Steel Leg vs. the Electric Dread EP with Public Image Ltd.’s Keith Levene and Jah Wobble?

I laugh about it now, but at the time it pissed me off. The guys from PiL had some downtime in the studio and were looking for a way to make more money—or rather take some more of Richard Branson’s money. They decided to go down and work on some solo stuff and asked if I would come down and work on some lyrics. So I’m in the studio’s toilets, doing guide vocals—I’d never written song lyrics before—laying them down for a start. I told them if they were serious, I’d come back and do the vocals for real.

Six weeks later, a record comes out. Which was scary, as I was really sticking my neck out on some of the lyrics. They didn’t know or care. They just wanted to make a quick buck. I never intended [it] for release by any means. What really pissed me off, though, was that on the cover of the record was a picture of a guy with a black bin liner [trash bag] over his head. Anybody who knows Don Letts knows that I wouldn’t have a bin liner over my head, let alone allow a picture of that to be used. That hurt me more than the fact that the record was crap.

Sad as it is, that’s a pretty funny first studio experience.

That’s not as funny as my first stage experience. I used to run this clothing shop on King’s Road in Chelsea. Everyone bought from there, one of them being Patti Smith. 1975 or something: We struck up a friendship based on her love of reggae. One particular artist she loved was Tapper Zukie, a toaster who happened to be a friend of mine and who happened to be in town. So she invited Tapper and I to see her at the Hammersmith Odeon.

So we go, and we’re backstage in the wings watching Patti do her thing. All of a sudden she pulls Tapper on stage and puts a guitar in his hand. Mind you, he’s a rapper. He can’t play guitar. So he looks at me, laughing, and I signal for him to play air guitar. Which he does to thunderous applause. Then she drags me onstage, and puts a microphone in my hand—which is problematic, as there’s no such thing as “air mic.” Luckily I was wearing dark glasses to hide my sheer terror. Never been on stage before. No desire to, either. So with Tapper miming guitar and Patti at my feet writhing on the floor I break into my heaviest Jamaican slanguage in a deep voice so the audience had no idea that I had no idea what the hell I was talking about—and they loved it.

“Music is the last place you’re going to find punk, now. But that spirit of expression, that railing against the mainstream, always pushing things forward, will always exist.”

By the time you got to Big Audio Dynamite were you more stage-ready?

Oh yeah. I loved that time and that band, and I got to write cool songs with Mick Jones. For a little Black kid from Brixton who couldn’t play shit, that’s a big deal. I’m proud of those songs. You have to know what you’re bringing to any equation, otherwise you’re baggage. With Mick’s help, I co-wrote 50 to 60 percent of Big Audio Dynamite’s songs. Especially the mix: we had those Jamaican bass lines, New York beats, Mick’s English rock-and-roll guitar, the samples and dialogue thing—that’s still what I like today.

You’ve documented so much of the British punk scene, past and present, on film and wrote about it in your autobiography. Are you done looking back?

Punk rock is an attitude and a spirit, like the force in Star Wars. Music is the last place you’re going to find punk, now. But that spirit of expression, that railing against the mainstream, always pushing things forward, will always exist. It ain’t some weird anomaly that happened in the mid-’70s. It’s an ongoing dynamic, living and breathing. The music was but one expression of it.

So how did you get to the first songs of Outta Sync? What gelled first?

The whole thing was kick-started by Youth. He was nutting me to do my own thing and gave me four or five basslines. I’m a sucker for bass, so those fired up my imagination, melodies started appearing. But not playing [laughs]. Few months before that, however, I hooked up with an Anglo-Italian producer, Gaudi, and with his expertise I created a soundtrack to my mind. The first track, I’m pretty sure, was “Outta Sync”—me feeling out of sync with the world, with technology, reflecting the duality of my musical and cultural journey. It evolved from there, as I didn’t have any intention of making an album.

“In lieu of an interview, you could just listen to Outta Sync and know about everything I have ever thought about the past, present and future.”

Why new music now?

What was good about the COVID lockdown thing is that it gave you a lot of time to think. But what was bad about it is that it gave you a lot of time to think. Add that dilemma, along with 67 years’ worth of thoughts—not headlines, just internal, ancient things from my perspective. In lieu of an interview, you could just listen to Outta Sync and know about everything I have ever thought about the past, present and future.

For better or worse, unashamedly, this album is very age-appropriate and grown-up. Then again, it’s like I sing on “Outta Sync”: “The young ain’t what they used to be / Neither are the old.” Because music changed the landscape. My generation didn’t become our parents. And it’s a cool place to be. I’m 67 and loving it. Me just being honest about what I like, and trying to make something that had a longer shelf life than a week—because that’s what I grew up on: music that changed your mind, not just your sneakers. FL