“I had this recurring dream that I was in war,” Nat Ćmiel tells me. “But it wasn’t a World War II vibe. It was very circus-like.” The Singaporean-British artist who records under the name yeule is describing an inspiration for their newest album, the guitar-driven softscars, over a Zoom call. “Everyone was trying to massacre each other, like in Battle Royale. Everyone around me was a loved one, and we were all fighting each other to the death, and I was covered in wounds.” They mention seeing a giant mirror in the dream—and the gashes that coated their body—before a faceless angel salvages them. “I felt like this was actually me trying to save myself. I think this was about how I dive way too much into toxic situations.”

Ćmiel talks with a steadfast attention to their work and how it corresponds to their life, as well as the interpersonal bonds they hold dear. But their panoramic perspective brings other elements into the fold, such as finding inspirations in Aphex Twin and Suzanne Ciani (“They’re not doing music by the book,” Ćmiel says, “they’re doing it by the feeling”), or how their cover of Shunji Iwai’s “fish in the pool” reflects their love for his film The Case of Hana & Alice and its coming-of-age themes of innocence lost.

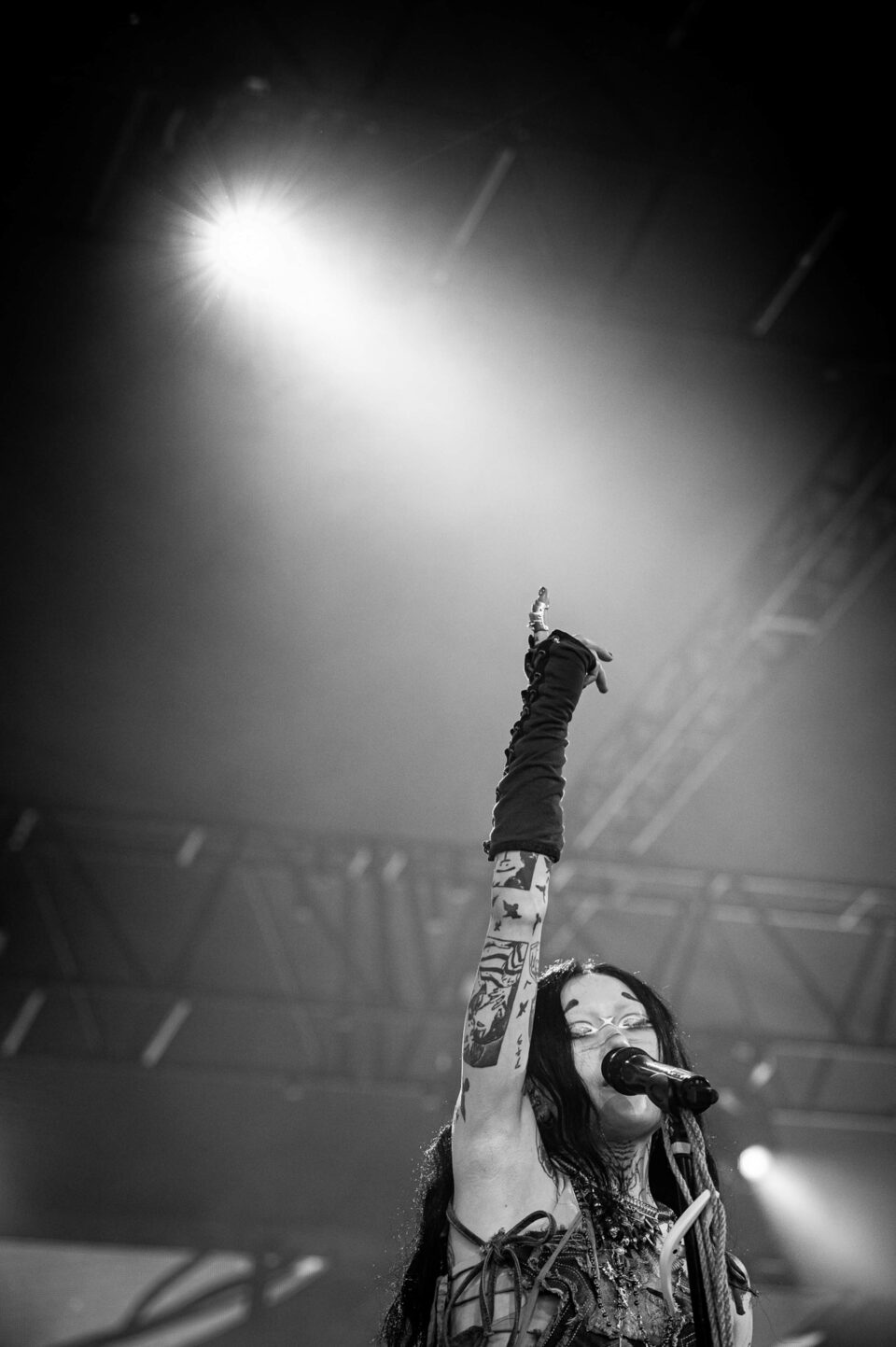

Ćmiel and I chat a few weeks before their softscars tour reaches my city, but whatever anxiety they may have around the production is subsumed by a show that’s immensely confident, gorgeously designed, and a cathartic extension of the album’s core themes. Joined on their US dates by SASAMI and Fitnesss, yeule’s live show recenters their music’s immediacy, sonically and emotionally. Adorned with fake makeup scars—an “X” between their eyes and claw marks by their mouth—Ćmiel’s vocals range from delicate reassurance to grunge-ripper screams.

The live band only adds to their dynamics: on “Electric,” each distorted chord and cymbal crash tears through the venue. It resembles something Ćmiel tells me about the process of recording softscars with their friend and co-writer Kin Leonn: “We wanted to create a ball of fire that would explode, so that everything else could be presented in the wreckage.” In the wreckage, and in their live show, comes a visceral, moving mirror into everything Ćmiel and I discuss about softscars—about connection, expression, and healing.

Read on for the rest of our chat below, and if you’re in LA you can grab tickets for yeule’s show this Sunday at The Fonda here.

What drew you to the guitar-based sounds you’re working with on softscars after the more electronic work in your past?

I was drawing from a lot of alternative, pop-punk, and emo music from the ’90s and early 2000s—the music I was listening to as a teenager. As I got older, I started listening to a lot more electronica, techno, and film scores, but I wanted softscars to be the record I wanted to make when I was a teenager. So I was drawing from Smashing Pumpkins, Sonic Youth, My Chem, Hawthorne Heights, blink-182… It was very much based on nostalgia and sensitivities to my youth and wanting to feel safe again. There’s a lot of people who can argue what emo is, but I feel like it’s mostly hatred and anger turned into sadness. You can hear that in the lyrics. You can have a song like “All the Small Things” or “Fat Lip”—it sounds happy, almost, like boyish vulnerability.

How did you want this sound that you’re talking about to work in tandem with the vulnerability of your lyricism?

For softscars to have so much anger and regret and intensity, it just reflects how much I’ve been holding in—tonally, with the inclusion of electric guitar and a lot more harsh noise. I was already integrating that through effects pedals and fuzz. I think we recorded one of the guitar tracks on “dazies” without a compressor by accident, and I was like, “Wait, it’s actually doing something really beautiful here!” That same intentionality of including stuff that’s not going by the book is a way to express our freedom with how we write music. We don’t really write classically; we write quite punky. It’s this whole ball of mess and emotion. Then we put it into the context of reality and it becomes understandable.

“As I got older, I started listening to a lot more electronica, techno, and film scores, but I wanted softscars to be the record I wanted to make when I was a teenager.”

You’ve talked recently about moving from some of the technological concepts on your previous records to something more human on this album. How did you find yourself reckoning with that when writing these songs?

I had an eating disorder since…I don’t even remember. I realized there was something wrong with the way I was thinking about eating from a very young age—like eight or nine. It wasn’t to do with the act of eating itself, it was about bodily processes. Bodily fluid, bodily function, bodily anything disgusted me up until I was a teenager. It took me a long time to get over it.

I always had this idea that, if you cut me open, I would just be what was inside my computer. That gave me feelings of safety and comfort—to know that there were just wires and circuitry, nothing wet in me. Just all dry and sparks and cables and nodes. I carried that into how I deal with my gender dysphoria. The first time I experienced gender dysphoria, I was around that age. It took me a long time to become comfortable and accepting of my own femininity. Being a nonbinary person, it’s difficult to explain being nonbinary and being femme-passing, androgynous, and wanting to exude my male counterpart through personality rather than through the physical.

I used to go deep into cyberspace. I was literally Serial Experiments Lain. I know that’s a total meme right now, but there’s videos floating around of me building PCs. I was really going through it at the time. I was building computers and gaming for 12 hours straight. I was doing everything by trying to do it perfectly. I didn’t want to do that anymore—I wanted it to be versatile and fluid. I kept a lot of first takes in [softscars]. “aphex twin flame” was all recorded in one go. It was so imperfect to my ears, but I just thought there was something very special about capturing that moment. It was me coming to terms with the fact that I can’t just use my old methods of coping to deal with these things.

With this idea of a “softscar,” does that tie into what you’re talking about with putting this authentic side of yourself onto the record?

All the lyrics came from my journal. One of the tags is “softscars”—scar entries in my life that have traumatic impact. Trauma implies “terrible,” but there are some scars in there as well that are pivotal to my life. Scar entries are really difficult for me to revisit, unless I’ve healed enough to be able to reread them. Scars that have healed over a long period of time become soft and blend in with your skin. There’s some things in my life that were so long ago that I felt like I lived a past life and I’ve been reborn. I still feel it in me, but I can’t really pinpoint what exactly it was. That’s what the scars are about: memory being lost, love being lost, life being lost.

“I always had this idea that, if you cut me open, I would just be what was inside my computer... Just all dry and sparks and cables and nodes.”

As a trans writer, I’m curious to hear about how you feel your art has been a means for exploring gender beyond a binary.

There were a lot of times at the beginning of my career where I felt like I was playing an act. I had long black hair in 2018. I looked like one of those typical shoujo manga characters. I tried to disconnect myself from my physical form when I was writing, but sometimes I couldn’t. I was like, “There’s something I need to heavily change.” And it wasn’t just my hair or physical stuff—it was the way I was singing, the way I was playing the music. Or the way I had the opportunity to have a producer and was like, “No, I’m gonna produce my own music, because I want to be alpha.”

I see that a lot with aspects of your performance, but I’m even thinking about how some of the lyrics on “cyber meat” deal with that.

“cyber meat” was very much me trying to make fun of really cringe music that sounds like that [laughs]. I don’t wanna name names and start drama, but I was trying to imitate that tone while making it about something heavy like gender dysphoria.

There’s a part of me that feels comfort in being able to identify as nonbinary because I find acceptance in the beauty of both sides. I think that carries over to performativity and songwriting and the ways I express things in music. When I sing and perform onstage, sometimes it’s feminine, sometimes it’s very masculine. If I were to dance the way I do onstage at a small group gathering at a church in Singapore, I’d be burned at the stake [laughs]. A lot of people meet me in real life and get surprised at the contrast. They expect me to be this weird fairy-core, mysterious feminine person.

Also, I feel like “cringe” is not a bad thing. I think cringe is just a feeling we get because we’re too afraid to deal with an emotion. That’s why a lot of artists are considered “cringe”: because they dive so deeply into certain aspects of human emotion that it scares people. That’s why people find furries “cringe.” Furries are fucking lit. They’re pivotal to this community and a lot of expression. There’s a lot of really smart furries out there. One of the furries discovered the Pfizer vaccine. That’s crazy! I’m an advocate and ally of furries.

“There’s a part of me that feels comfort in being able to identify as nonbinary because I find acceptance in the beauty of both sides. I think that carries over to performativity and the ways I express things in music.”

What role does translating all this to a live setting play for you?

Performativity wasn’t something that I considered early on. But then, as my trajectory led me to playing a lot live, I realized, “Oh fuck, I can’t sing ‘Pretty Bones’ live.” I had to change a bit of it to hit all the words, because it’s so artificial. “Don’t Be So Hard on Your Own Beauty” has that, too; the live version has breaths so I can sing the lines. I think, compositionally, there’s a lot of planning that goes into integrating what we record and what we write, based on how we envision playing it live. There’s a story to be told in a live set, and I like having a lot of fluidity.

The last shows I did with my band were so cathartic and so explosive. A deep part of my artistry has to do with my own personal struggles, and I tend to be drawn to people who are like-minded. Most of the time, my music brings me to people who are meant to be in my life. [I find] a lot of understanding of myself and my music through queers, or people of color, or trans people who have touched me. I just think that queer voices are so fucking important. This record is not just a collection of songs, but a journey I want to share. FL

yeule