Whether viewed from their Dada-esque dystopian worldview or their quirked-out brand of electro-punk, Devo had a pretty good idea that the future was about to be screwed beyond repair. The only thing that Mark Mothersbaugh and Jerry Casale—Devo’s co-founding brain trust—got wrong was how quickly hardcore devolution would take hold, how lasting its effects would be, and how enduring their role among our disintegrating culture will continue to be. At least if their new 50-song retrospective (50 Years of De-Evolution 1973-2023), their early-era box set (Art Devo: 1973-1977), their soon-to-screen documentary (Devo, from Tiger King director Chris Smith), and their 2023 tour are any indication of future-primitive re-degeneration.

“We were consciously optimistic about the future, and hoping that devolution wouldn’t exist,” says Mothersbaugh with quiet concern in his voice. “We were thinking that we were sounding an alarm, and that people would change course—which they haven’t. We didn’t create devolution. We just used it as a forum to talk about the condition of man on planet Earth.” On top of it all, as a buggy visual artist, a constantly composing music-maker for film and TV, and a loving father and husband, Mothersbaugh remains fascinated by all brands of mutation, yet in a far more communal fashion than he did at Devo’s start on the revolutionary Kent State campus of 1970. He sees his history and that of Devo’s as a constantly changing set of circumstances—he refuses to stand still as an artist so that Devo, too, remains an ever-devolving, even revolutionary concept.

Thinking back to Kent State’s incredible art department and being influenced by Nino Rota’s use of ancient instruments on the soundtrack to Fellini Satyricon, it’s clear that radical cinema and other visual art were an important part of his soon-to-be band’s development. Of meeting his partner in Devo, Mothersbaugh recalls Casale coming into the school’s screenprinting studio and asking him, “‘Hey are you the guy that’s sticking up pictures of astronauts holding potatoes on the moon all around campus?’ And I was—on car bumpers, on lockers. I was doing what Shepard Fairey made very famous with his Andre the Giant “Obey” art. But I was doing it in 1969.”

A conversation about potatoes blossomed into a friendship before evolving into a band—something Mothersbaugh wanted to form since the age of 12. “I was really being tortured playing keyboards for years after I had built this home synthesizer. My early stuff sounded like prog-rock and religious music. I played in a strip bar for the women to dance to, and in churches. But I wound up having to play stuff like ‘Court of the Crimson King’ on their church organ because I didn’t know any appropriate hymns.”

“We were consciously optimistic about the future, and hoping that devolution wouldn’t exist. We were thinking we were sounding an alarm, and that people would change course—which they haven’t.”

Talking about each man’s vision of what a band should be while still at Kent State, it wasn’t until Casale happened upon the book In the Beginning Was the End: How Man Came Into Being Through Cannibalism that a theatrical concept came through that both artists could sink their teeth into. “That book talked about devolution,” recalls Mothersbaugh. “And that wasn’t the first time that devolution as a concept reared its head—in the 1930s, there were religious pamphlets that spoke of it. I found one titled ‘Jocko Homo,’ and on its first page was a picture of a devil on a staircase leading to heaven laughing, but with options on each step reading things like ‘World War I,’ ‘atomic warfare,’ ‘drugs.’ On the devil’s chest, there was the word ‘devolution.’ That was 1933. It was a reaction to Darwinism. That just gave us more fuel to formulate what Devo could mean.”

By Mothersbaugh’s way of thinking, rock and roll had already been around for 20 years when Devo started up in 1973. It was about time for something radical and truly new to take shape. “I was looking for new sounds, and primitive synths were the way to do it with their plastic sounds and effects like V2 rocket mortar blasts—the headache sounds from Anacin commercials, or Italian sci-fi film laser beams,” he says. “I wanted to take those abstract sounds and insert them into a musical format. Jerry was doing this raw, basic blues stuff, and I was doing this electronic noise. We referred to our pre-Devo sound as ‘Art Devo.’ It was very bluesy, but with a giant walking-through-the-mud sound to it all. Like Sun Ra playing with his fist. Or the Roxy Music album with Brian Eno taking that synth solo on ‘Editions of You’—an abstract solo that overshadowed the whole album.”

“Those [early] sounds were so hardcore that when we did start playing live in Cleveland and Akron—the only places that had clubs where we were tolerated—people would pay us not to play.”

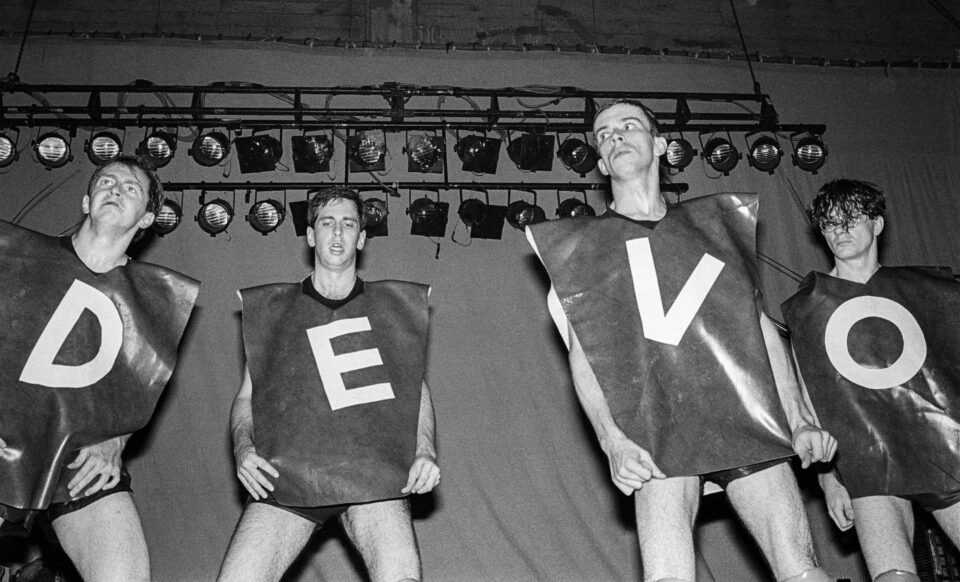

DEVO 1981

The new Art Devo box covers that rough early era with Mothersbaugh recalling that primordial industrial roar fondly. “We hadn’t been playing live gigs yet—we just recorded things in my basement, all purely conceptual, all pure art. It truly was about how far we could take this. Some of it sounds naïve. A lot of it, though, sounds more hardcore than anything we put on any of our official releases. In fact, those sounds were so hardcore that when we did start playing live in Cleveland and Akron—the only places that had clubs where we were tolerated—people would pay us not to play.”

Eventually, Mothersbaugh and Casale took their willingness to repel into consideration and decided that if they actually wanted to have a career in music, something had to change. With that, the Devo of 1976 began to temper their noise. “We learned that rebellion didn’t work at Kent State, that when dictators and the government got tired of you and your antics, they shoot you,” says Mothersbaugh. “Who does change things? One day, I remember hearing Pachelbel’s ‘Canon’ while I was painting. Suddenly there were lyrics, which I never knew existed: ‘Hold the pickle, hold the lettuce, special orders don’t upset us.’ It was the Burger King ad. Oh fuck, that’s how you do it. Just like Madison Avenue did. So we started making our sound more succinct, more palatable, and simpler to understand.”

After decluttering their sound, Devo began touring the country until they wound up in New York City and the heralded Max’s Kansas City nightclub. There, they met avant-garde gods Brian Eno and Robert Fripp at the height of their NYC fame—and both of them wanted to produce the Akron band. “We were in awe of other bands who were getting better responses, so we sped our songs up. My brother Jim moved to being a circuit bender behind the scenes, we got Alan Myers—the human metronome—[on drums], and Bob Casale came on board on guitar so I could be a proper frontman. That changed our reception markedly. The first time we played New York, we became the band to see. Everything changed overnight—our guest list now had Dennis Hopper, Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, all of The Rolling Stones and The Beatles.”

Recalling one particular night at Max’s Kansas City, Mothersbaugh continues: “I remember waiting to go backstage after the show when two guys—totally drunk—come tottering up to us: John Lennon and Ian Hunter. And Lennon comes up to the window of the Econoline van we’re using and sticks his face in the window and begins yelling [the refrain from ‘Uncontrollable Urge’] while spraying me with spittle. Lennon knew it was a permutation of his ‘She Loves You,’ and it was kind of wild—John Lennon just spit in my face and sang my own song to me. At that moment you could’ve run me over with a truck and I would have died happy.”

“My early stuff sounded like prog-rock and religious music. I played in a strip bar and in churches. I wound up having to play stuff like ‘Court of the Crimson King’ on their organ because I didn’t know any appropriate hymns.”

Despite having been spit on by a Beatle and befriended by Eno and Fripp, Devo’s fates were truly changed when they met David Bowie shortly after Eno offered to pay for studio time in exchange for the chance to produce the band. “The next week, Bowie shows up at Max’s, sees the first set, comes back before the second set, then jumps on stage before we came out again and introduces Devo as ‘the band of the future—I’m going to produce their record in Tokyo this winter.’ Which was amazing, but news to us.”

The next thing you know, Devo winds up at Conny Plank's studio in Cologne when Bowie shows up to lend a hand. As Bowie had commitments in Berlin to film Just a Gigolo, he relinquished his production duties, leaving Devo in Eno’s capable hands. “Bowie would spend the weekend with us, then head back to Berlin,” recalls Mothersbaugh. “He was great. I’ve been archiving every tape of us, and I found our first album and its original track listing. Eno had such beautiful handwriting. There was one tape marked ‘Brian and David background vocal.’ Then there was ‘David’s guitar part’ and ‘Brian synth part,’ and others just like it. The two of them were playing stuff on top of our stuff when we weren’t there.

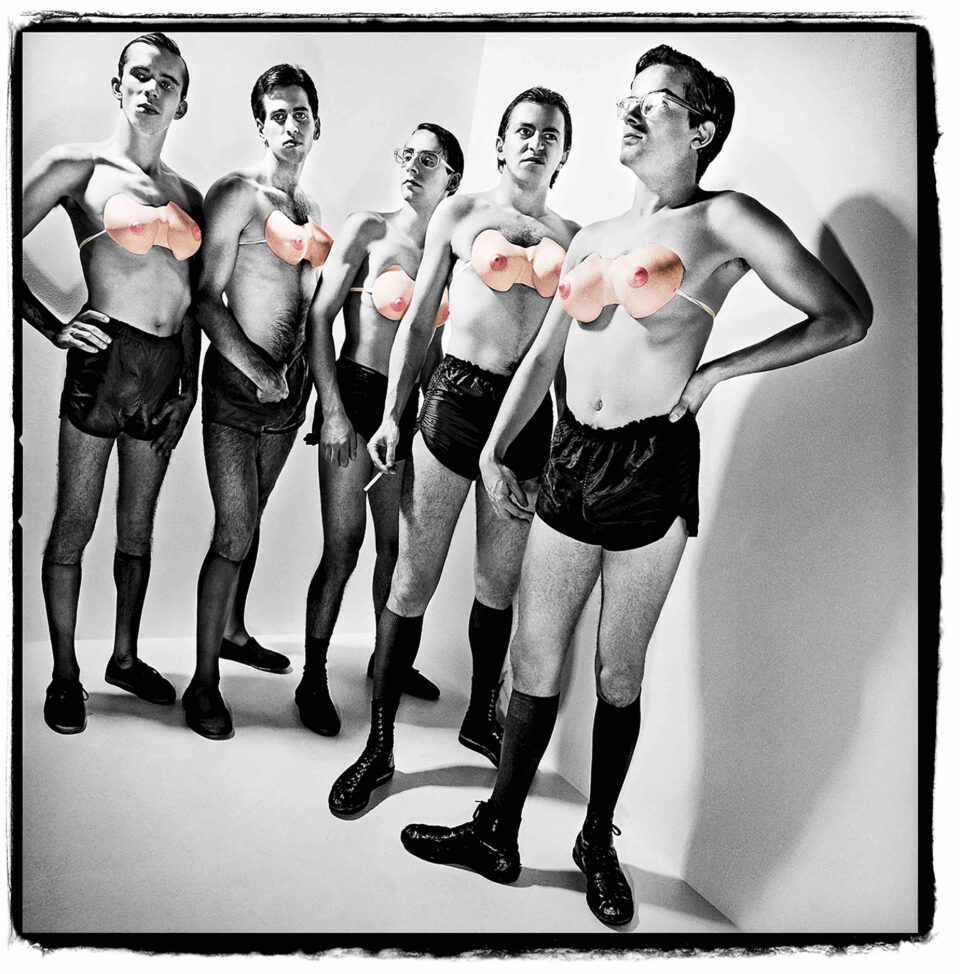

DEVO In Concert London 1978

“Ultimately,” he continues, “Brian and David’s background vocals did make it onto songs like the ‘Nine-nine-nine-nine’ part of ‘Uncontrollable Urge.’ A lot of what Eno wanted to do was make Devo more beautiful with harmonies—not make it wilder, as we expected. In the end, when Devo was mixing with Brian, we would go in and turn the faders down. I didn’t like everything they did. We’d do the playback and I remember reaching down and taking out the things they put on. I would do it while staring straight ahead as if nothing was wrong, and Brian’s head would snap around. He never confronted me, though. It was my version of Oblique Strategies.”

Mothersbaugh also recalls not signing to Bowie’s Bewlay Bros. management team in the late ’70s because the financial terms of the agreement were not to Devo’s liking. “People from all over the world claimed they were our manager, our label bosses, our agents. All sorts of magazines at the time had printed this stuff as fact. We passed out so many demo tapes—we gave them to everybody, because we were trying to get a deal. When we got that first offer from Bewlay Bros. to manage us, it just didn’t seem tight. There were no upsides for us in the contract. And by that time, we’d already screwed up enough on our own to know what we didn’t want. We could keep screwing up on our own—and trust me, we made plenty of our own mistakes after that.”

“John Lennon just spit in my face and sang my own song to me. At that moment you could’ve run me over with a truck and I would have died happy.”

From that point forward, 1981’s New Traditionalists, 1982’s Oh, No! It's Devo, and 1984’s Shout were all Devo-produced. Did the band taking its own sonic reins mean that these three final Warners albums of the decade were Devo-licious, pure and unfiltered? “On the first three albums, our record company didn’t give a shit about us or what we were doing,” Mothersbaugh recalls. “They signed an art band, just like they had by signing Captain Beefheart. They never paid much attention to us—we weren’t a band to over-budget or throw televisions out of hotel rooms. But once we scored a hit on [1980’s] Freedom of Choice, we’d then get label heads popping into the door of the studio, reminding us, ‘Hey, do what you want, just don’t forget to come up with another “Whip It.”’ That didn’t help us, especially since ‘Whip It’ came from our roots, and certainly not from trying to purposely come up with a hit. Once the record company became intrusive, Devo became less fun. There was a forced artificiality to working on new albums.”

In-between Shout and their first album for the Enigma label, 1988’s Total Devo, Mothersbaugh began work on the first of his soundtrack showcases with the late, great Pee-wee Herman. Starting with Pee-wee's Playhouse in 1986, Mothersbaugh turned his musical vocation to a different brand of collaboration than that of a band, and found great favor and fortune. “Devo would do an album—write for three months, record for a month, spend a month putting together costumes, promo materials, and a live show, rehearse, then tour for six months, come back and do it all again—six times over before Paul [Reubens] asked me to do Pee-wee’s Playhouse. He sent me a videotape of the show on a Monday, and I wrote 12 songs that day. On Tuesday, I recorded them. On Wednesday I put them in the mail to him. On Thursday and Friday, they mixed it into the show—and I did that all again the next week. I got the opportunity to do an album every week without leaving my studio. This was incredible.”

With the summer 2023 passing of Paul Reubens, the happy, lingering memories of working with the conceptual artist and children’s TV icon are fresh. “Paul’s only direction to me when we started working together was to work in extremes. I could do that. It was an amazing project—one where a bizarre artist had total control and final say on a television show for kids. There were things we got into those shows where I was certain the censor would come down on us. Any other kids show, you could just sense that there are lawyers sitting on top of the entire production. Not with Pee-wee. Somehow we circumnavigated that to make this original, fantastic TV show. And we became greater friends after the show ended. We used to hang out together in Palm Springs with songwriter Allee Willis and her girlfriend Prudence Fenton, who produced Pee-wee’s Playhouse. We’d always find the weirdest themed hotels—coal miner hotels, Russian hotels—and go to junk stores. We shared a really kitsch aesthetic.”

“Once the record company became intrusive, Devo became less fun. There was a forced artificiality to working on new albums.”

Getting back to the future-present, rapping about the upcoming tour (“Not our last tour, either—that was an over-anxious promoter’s error,” he assures me) and double box set drop, Mothersbaugh remarks about how the last new LP from Devo—2010’s Something for Everybody—is represented on 50 Years, and what it meant when it came to new music. “We wanted to do something together, but I had different hopes for that record: to go backwards and make something noisier, like the first album, to use those older instruments. Jerry and the two Bobs wanted to go forward and use modern electronics. We tried jamming in the basement, but to no real avail. It was like drinking castor oil. There are some great songs on that record, it just could’ve been different.”

While opening up a carton of Devo’s fresh yellow costumes for the 2023 tour (“We had to find a new company, as the old uniform maker went out of business after 50 years”), Mothersbaugh considers what new Devo music could sound like, stating that it could come in shorter, sharper blasts in the future, a sound more diverse in its tonality but with dramatic visuals and the intensity of youth put into replicant compu-robotic form. Also, surprisingly, any new music that Devo makes going forward will borrow liberally from the noisiest parts of their past. “Playing live was always integral to who we were, even if we go into more esoteric territory,” Mothersbaugh concludes. “Perhaps going forward on tour, in 20 years, I’d like the essence of me to be in a computer so I can be like one of those delivery robots, the cute damn things we have out in West Hollywood. If your sentient being can be put in electronic form, it would free us from all of the physical liabilities and humiliations we go through every day.” FL