Synth virtuoso Vince Clarke is arguably one of the most influential musicians in electronic rock: he co-founded Depeche Mode and was a main songwriter on Speak & Spell, the group’s 1981 debut album (including writing “Just Can’t Get Enough,” their first single released in the US). Later that year he formed the band Yazoo (a.k.a. Yaz in North America) with singer Alison Moyet, scoring hits such as “Situation” and “Don’t Go.” Then, in 1985, he created Erasure, a duo with singer Andy Bell; together, they’ve had numerous international hits, including “Oh L’Amour,” “Chains of Love,” and “A Little Respect.” Erasure have remained together ever since, releasing 19 studio albums to date.

One thing Clarke has never done in his long and prolific career, though, is branch out entirely on his own—but that changes this week when he releases his debut solo album, Songs of Silence. During a recent Zoom chat from New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood, he tells me that he created this album while isolated in his home studio during the darkest days of COVID, which accounts for the way it sharply departs from the often exuberant work he’s done with his various bands. Instead of catchy choruses and traditional pop-rock arrangements, this is an ambient album that’s almost entirely vocal-free (aside from some wordless contributions from opera singer Caroline Joy). Still, even this somber mood can’t obscure Clarke’s knack for intriguing melodies and evocative soundscapes, putting these 10 tracks on par with the rest of the work he’s done over the past four decades.

Clarke shares why he finally decided to go solo—and how he got into music in the first place—in the conversation below.

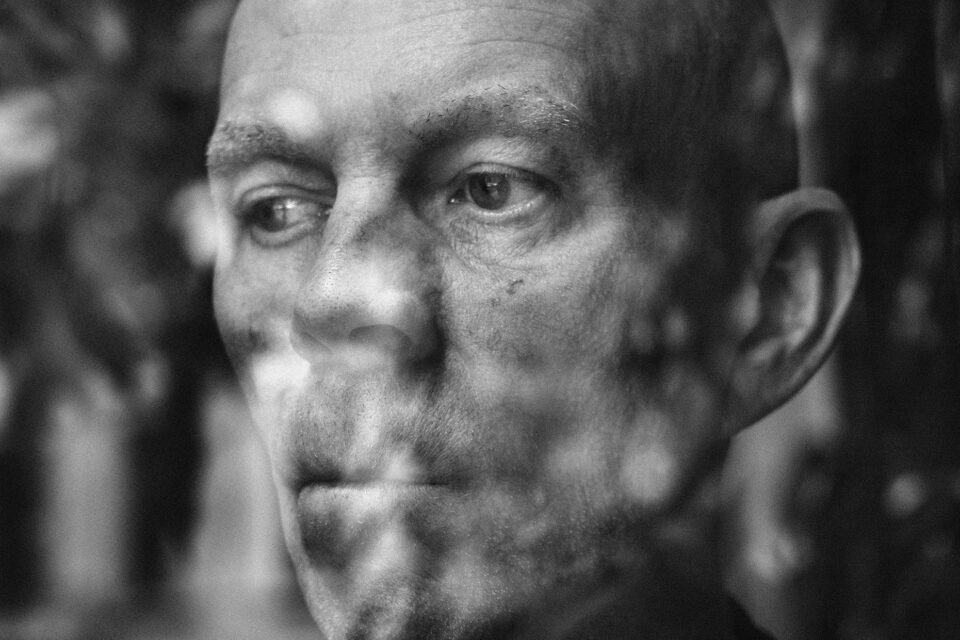

©Eugene Richards

What made you decide that it was finally the right time to do a solo album?

I had some time on my hands, and I just started experimenting, making tracks. There was no real intention to actually turn those tracks into an album—it was really just for my own sanity, especially over COVID, when everything was shut down. I’m not very good at watching TV, so I tend to spend a lot of time in the studio. And this was just a challenge: I was trying to do something obviously different from the stuff that I’ve done in the past, and create something that would be interesting without having to rely on traditional pop song arrangements with verses and choruses. The record company was curious to see what I was up to, so I sent them the tracks and they suggested that I release it as a record.

I was always curious as to how people make non-vocal music interesting, how a sound or an atmosphere can keep you captivated. So my system, basically, is that I needed to be captivated and interested in the sounds that were coming out. I would listen to these tracks and there would be a point where I’d go, “Well, now I’m bored, I need some change to happen there.” And then the tracks would build up like that. But it was all about keeping me interested.

How does it feel to release something under your own name, as opposed to doing it as part of a band?

It’s very strange. And it’s very naff, really, in a way. I mean, “solo artist”...I don’t know, it’s a bit cringey, I think. Obviously now I’m making a lot more decisions on my own, stuff that I always left to Andy Bell—things like titles and artwork direction and the order of the songs. He was much better at it than I was, and he enjoyed doing it. Even doing interviews about yourself is a bit weird, really.

What drew you to playing electronic-based music in the first place?

In the beginning, when I first started making music, I was playing folk music, really. I was playing acoustic guitar. Very badly. Then we progressed—or digressed, I’m not sure which—to electric guitars. And then, because our guitar playing didn’t seem to be getting any better, we bought synthesizers, which were much easier to play.

“I was trying to do something obviously different from the stuff that I’ve done in the past, and create something that would be interesting without having to rely on traditional pop song arrangements.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, synthesizers were notoriously finicky. Was it ever nerve wracking as you were touring because of that?

Yeah, there was always something going wrong, especially when we played places where the power supply would be erratic. Back then, the synthesizers that we were using, if you switched them off, then they lost their memory. It was that crude. So that presented lots of problems for us in the beginning. But later on we always had a really great team of people around us to make sure those things didn’t happen. But yeah, it was hair-raising sometimes. We did a lot of early shows where the gear would just stop working, and then Andy would have to sing acapella. He’d sing Beatles songs. And then whilst he was singing, we would try desperately to fix the gear.

How did you know that you should be a professional musician in the first place?

I just got fed up with working in factories. When I left school, I had lots of jobs, very-labor intensive kinds of jobs. Then I saw the film The Graduate with Dustin Hoffman. At the time, I’d been learning guitar. I saw that film and I heard the music of Simon & Garfunkel, and I was completely blown away. It was the first time I realized that what I was hearing, I could actually do because it was done on acoustic guitar. So I went out the next day, bought the songbook, and learned every song. Suddenly, music wasn’t something you just saw on Top of the Pops; it was something that was within your grasp, something that you could achieve.

How did you make the leap from learning other people’s songs to creating your own?

I kind of remember the very, very early songs I started writing. They were almost like nursery rhymes, really, because I only knew a few chords, so they were obviously based around just those. I mean, I wasn’t thinking, “I need to be a songwriter.” It just felt like the natural thing to do, and something that I could do. The music that I liked back in the day, like early folk songs, they’re quite simple, really. I would never have gotten into jazz or anything that was too musicianship-ish because I just didn’t have the talent for it, or the patience to learn it.

“I’ve spent more time watching synthesizer tutorials than films on Netflix.”

How did you then make the switch from acoustic guitar to the synthesizer?

Me and [Depeche Mode’s Andy] Fletcher used to rehearse in my mum’s garage. I don’t know why we rehearsed; we never played anywhere. I mean, we may have played at one of the pubs or something once or twice. Martin Gore was a friend of Fletcher’s; they went to the same school, and we knew that Martin had bought a synthesizer. No one else in our hometown had a synthesizer. He started playing with us, and then we realized that we could actually make more interesting sounds with keyboards than our dreadful guitar playing. At the time, people like Gary Numan and The Human League were coming out as well, so that was a big influence on us.

What do you hope people will think or feel when they hear Songs of Silence for the first time?

I don’t really care, to be honest. I mean, I really enjoy the process more than the other bits of making and releasing records. Process means everything, because you’re learning. I’m learning new things all the time. In this particular field of [electronic] music, it’s forever expanding and new things are coming out—new ideas, new sounds, new ways of making sounds—and I love all that. I’ve spent more time watching synthesizer tutorials than films on Netflix. Especially with the new modular synthesizers that are coming out now, the Eurorack stuff. It’s never ending—and I love it. FL