For a genius of immersive installation art and postmodern multimedia that touches on macabre magic realism and the phantasmagoric, Tony Oursler is remarkably grounded. In conversation, the NYC-based artist is down to earth when discussing his freshly commissioned works found within a new group show, Smoke and Mirrors: Magical Thinking in Contemporary Art, taking place in Palm Beach County at the Boca Raton Museum of Art through May 12, which features works that speak to (but refuse to converse easily with) 21st century concerns such as the duplicity of deepfakes and AI.

Yet if you’ve followed Oursler’s creations in his variety of chosen mediums—sculpture, performance art, painting, and his signature video dolls—since his start in the 1980s, no matter how creepy or otherworldly his aesthetic, there’s something tactile and fleshy about that which he exhibits. Along with warm and touchable intimacy comes a willingness to collaborate, a playful conviviality he’s shared with the likes of Jim Gibbons, Kim Gordon, Tony Conrad, and, most famously, David Bowie.

Thinking about how the sinister spirit of his early video tape works such as 1980’s The Loner and 1984’s EVOL, or primitive installations like 1982’s Son of Oil, touch on his newer pieces, Oursler is quick to connect the dots between his past and the present. “The molecules in your body change every seven years, and I value evolution a lot, but there’s something about the primary visual base that I developed on the idea of willing suspension of disbelief where I trusted the viewer’s interpretation of things over the canon,” says Oursler. “The early works were heavily in response to popular culture—like having EVOL look at romance and images from Hallmark cards to the psychedelic agent that the US military used to experiment on the troops and freeforming the content in the moment.”

Exploiting pop culture through social phenomena, examining the high-low relationships of industrial design, and turning mass-media concepts on their head with frozen images and a playful painted iconography going back to the caves of Altamira led Oursler to create kaleidoscopic, all-media installations. “That kaleidoscope vibe certainly carried into everything I do now,” he says of the idea of “using a palimpsest to look at the cultural moment, which has stayed with me from those early video tapes up until the present. Only now, my work has a wider range, looking at deep histories about the future and collapsing it all into one work, for better or worse.”

“I think the work I was doing freed the moving image from its cage. The dolls were electronic escapees that found their way into the world.”

The thought of suspending disbelief reminds me of where I came into Oursler’s work: that of the spectral video doll or “electronic effigies”—ratty, hand-fashioned cloth figures brought menacingly alive through genuinely creepy techy video projection, ragged totems such as Judy that looked deep into the close relationship between multiple personality disorder and mass mediation. “It did turn audiences on its collective ear,” says Oursler in regard to the magic moment of the video doll. “I’d all but given up on the art world as I felt it would never accept the moving image of it all—and this was at the beginning of computer stuff in art. Photography, video art, computer art…it was all still segregated. But second-generation conceptual artists like myself don’t think that way, and the video doll allowed me to stop teaching in Boston. I think the work I was doing freed the moving image from its cage. The dolls were electronic escapees that found their way into the world.”

Cardiff Giant (working title), 2023, 121in x 33in x 17in

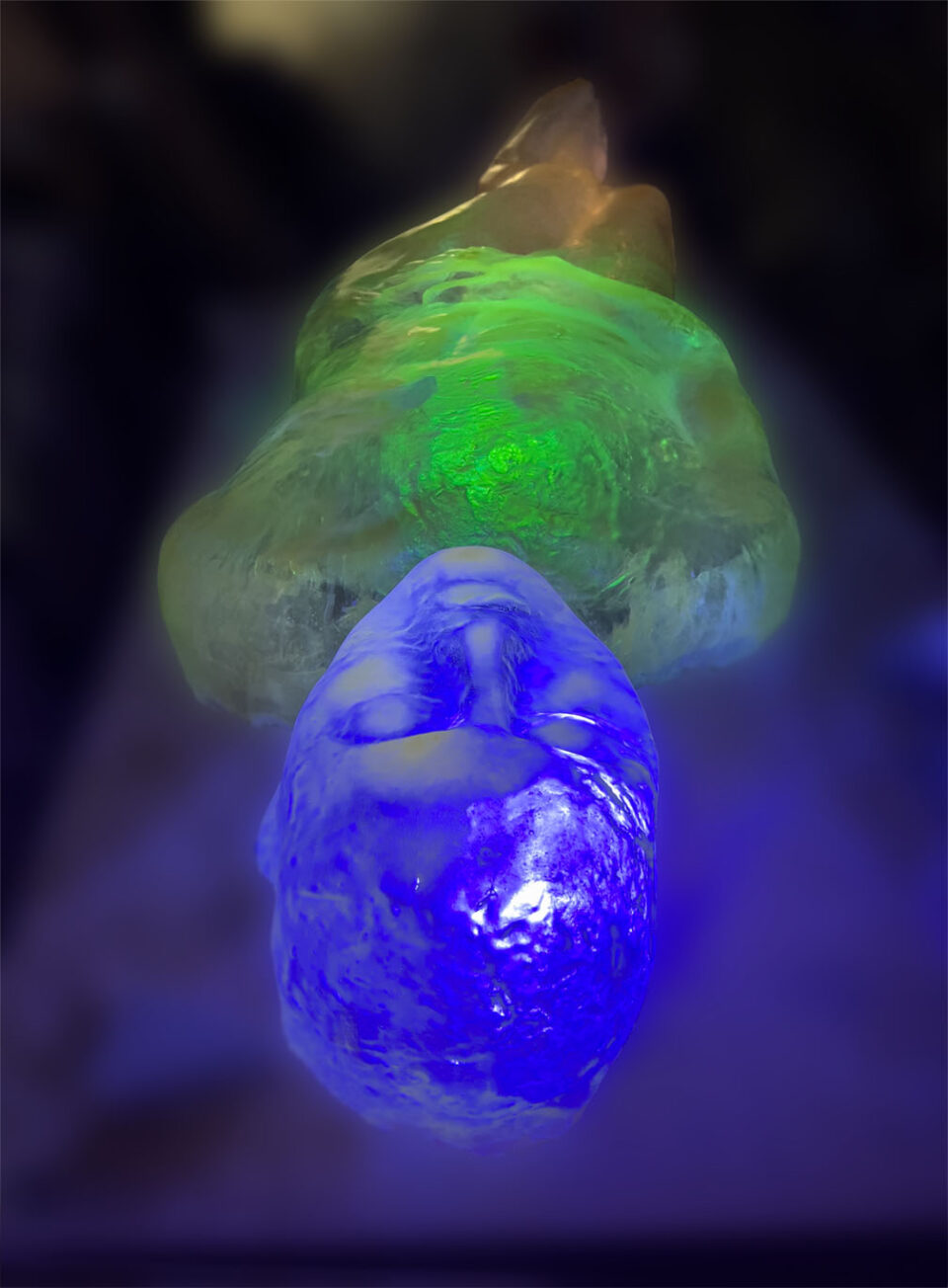

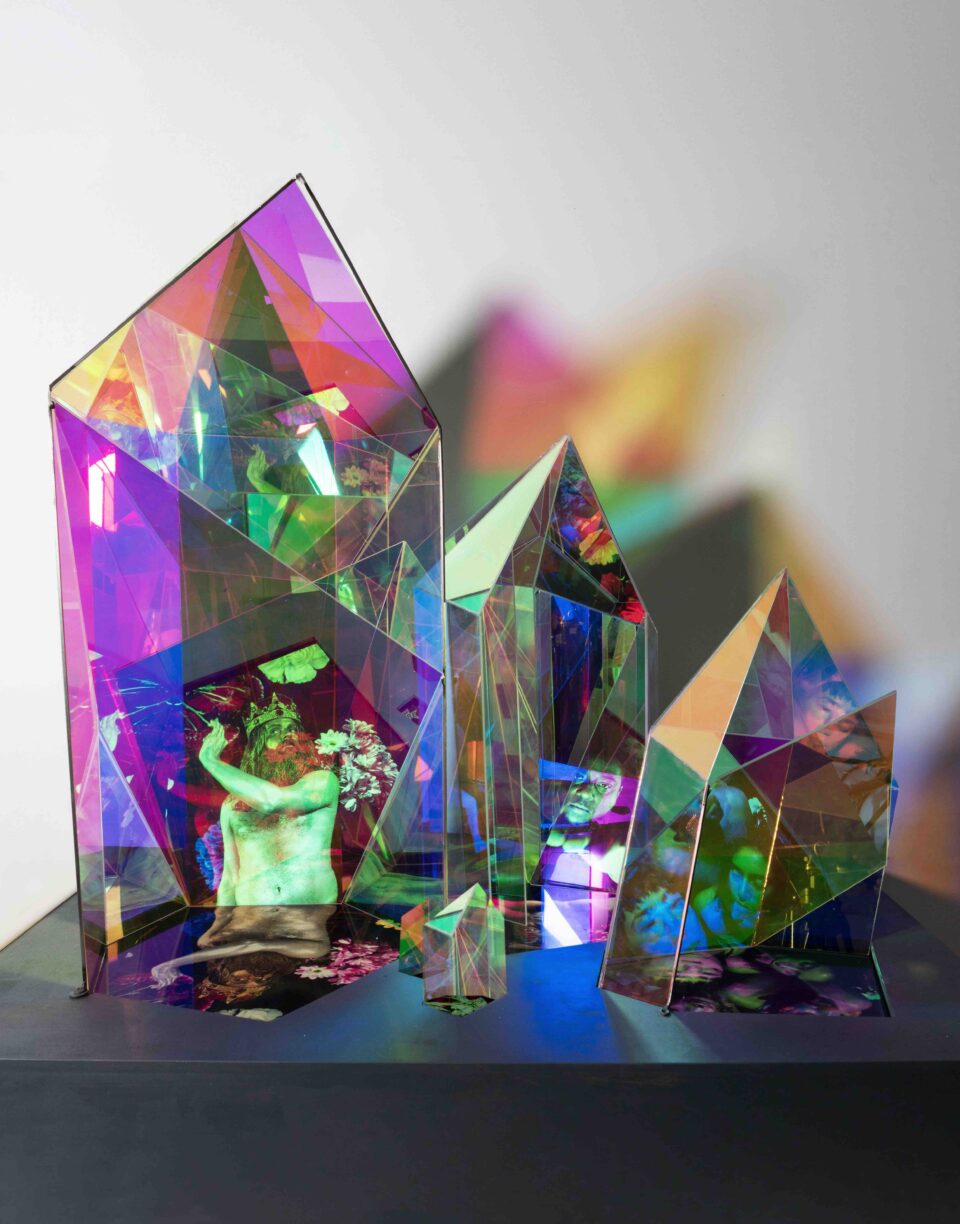

Crystals (working title), 2023, dichroic acrylic, wood, LCD screen

With the line between media and the real world broken by Oursler’s dolls—to say nothing of their projection onto trees, cloth, and other textural, proactive landscapes—its interrupted projection created something that the mind’s eye couldn’t easily process. “The viewer automatically became a collaborator with the dolls, which was always my goal: to stimulate the most visual part of the brain. Plus, I think people were disturbed to have art that spoke back to them, literally. Really aggressive stuff, too.” Additionally, Oursler mentions how he wished younger artists would interact with more friction toward the current technological norms rather than play nice with present-day multimedia, “to utilize the outer edge more often—to use the internet, phones, and streaming as a creative space rather than a null-and-void, passive space. We’re looking at screens for hours a day. It can’t be a corporate top-down situation.”

Transgressively minded audiences have long been thrilled with Oursler’s work. So, too, are old- and new-found collaborators, who, like William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, created a third-mind aesthetic. One such collaborator was David Bowie, with whom Oursler crafted everything from live video backgrounds for the musician’s concerts, to Oursler’s own video shorts (e.g. the now-rare Empty, using Bowie as its eerie bighead narrator) and the video for Bowie’s Berlin-inspired ballad “Where Are We Now?”

Bowie was different from any of Oursler’s other collaborators. “First off, my parents were vexed,” says the artist with a laugh. “He was intelligent, friendly, funny, and he really knew what he wanted and would call the shots. We used to trade stuff—my material for his stage shows, and for his appearance in some of my short films. No money changed hands. And there’s one unreleased project that Bowie and I did with Glenn Branca that has yet to see the light of day. In many cases, such as ‘Where Are We Now?,’ it was Bowie’s imaginings of my studio and my work that fueled our collaboration.” A recent Oursler collab with Foo Fighters (which started at Bowie’s 50th anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden, where Dave Grohl played in tribute to Bowie’s inspiration), “The Teacher,” carries the DNA of “Where Are We Now?” as the specter of losing his mother and the band’s drummer Taylor Hawkins haunts the recent 10-minute video.

How Oursler got to his newest work—the five-plus pieces and installations of Smoke and Mirrors—is a continuation of the artist’s love of pseudoscience and the paranormal. “There’s a lot more of my friends who are on the other side, so to speak, than when I started out,” says Oursler of those who’ve passed away over the years. “Your relationship to death changes as you get older. Memories change. In my earlier work, I was happy to look at things more abstractly. With time, when you think about how many of your friends are gone, the images and the work derived from it all becomes much more poignant—the idea of being able to connect with those who are gone. It would be great to create a telephone connection to the other side, or a séance table that worked.”

“With time, when you think about how many of your friends are gone, the images and the work derived from it all becomes much more poignant—the idea of being able to connect with those who are gone.”

Until then, there are Oursler’s haunted works such as the spiritually iconographic mAcHiNe ELF, the vaporous Cardiff Giant sculptures, the cartoon horror of the Creature Features gallery, the further adventures in levitation magic and menageries of Imponderable’s film-and-flowchart-filled installation, and the colorfully jagged Crystals that line the Boca exhibit. “I’m very interested in how people are re-enchanting the moment by using things that are newer, high-tech approaches and back-to-nature, older power of sound and color vibrations—these binaural beat meditations and new age vibrations,” he says. “The utopian world has shifted from a technological place where in 2000 everyone thought the internet would free us to now, where people are horrified with what’s on the internet. Utopia now has its back-to-nature paradigm, one with druidic activity. I’m not debunking anything. I’m trying to identify and chart it, through psychedelia.”

Merma, 2022, fiberglass, resin, acrylic paint, glitter, fake hair, gemstones, video projection, sound, 36in x 24.25in x 58in / Performed by Dominique Bousquet

Fairy (working title), 2023, aqua resin, cast acrylic, acrylic paint, bronze, plexiglass, fake hair, steel, inkjet print on canvas, digital moving image with sound, sculpture: 64in x 8.5in x 8.5in, canvas backdrop: 86in x 42in / Performed by Katiana Rangel

Biblical literalism and petrified dinosaurs (at least in the case of the ancient-yet-modern Cardiff Giants) are part of Oursler’s recent mindset in creating for the Boca Museum commissions. But he laughs thinking about the fact that Mike Johnson, the new Republican Speaker of the House, is indeed a Biblical literalist. “It’s more relevant than I thought it would ever be,” Oursler says with a laugh. “My ‘time traveling’ giant exists in several different dimensions and is a great public artwork for our time with all of its conspiratorial stuff from the internet and the footage I shot in front of the courthouse where Trump is being tried. This stuff is what I live for.”

The Amazing Randy—the late, legendary magician who was unafraid to portray the form’s deepest secrets—too, is a big part of why and how Oursler crafted the installations and films of Smoke and Mirrors. “‘The Great Debunker,’ as he was known, was also a part of Alice Cooper’s stage shows, so I vectored off that in talking about illusions, horror, and comedy.”

As for how the genuinely enthused Tony Oursler plays well with others during the Boca group show (which also features 29 additional acclaimed artists), he’s pleased by the company he’s keeping and how they’re all taking to the notions of deception, deepfakes, and duplicity. “It’s a great group of artists, all kindred souls with a love for magic and the creative process.” FL

Flatwoods Monster (working title), 2023, wood, aqua resin, cast acrylic, acrylic paint, fabric, steel, fan, aluminum foil, LED light, video projection, 96in x 36in x 18in