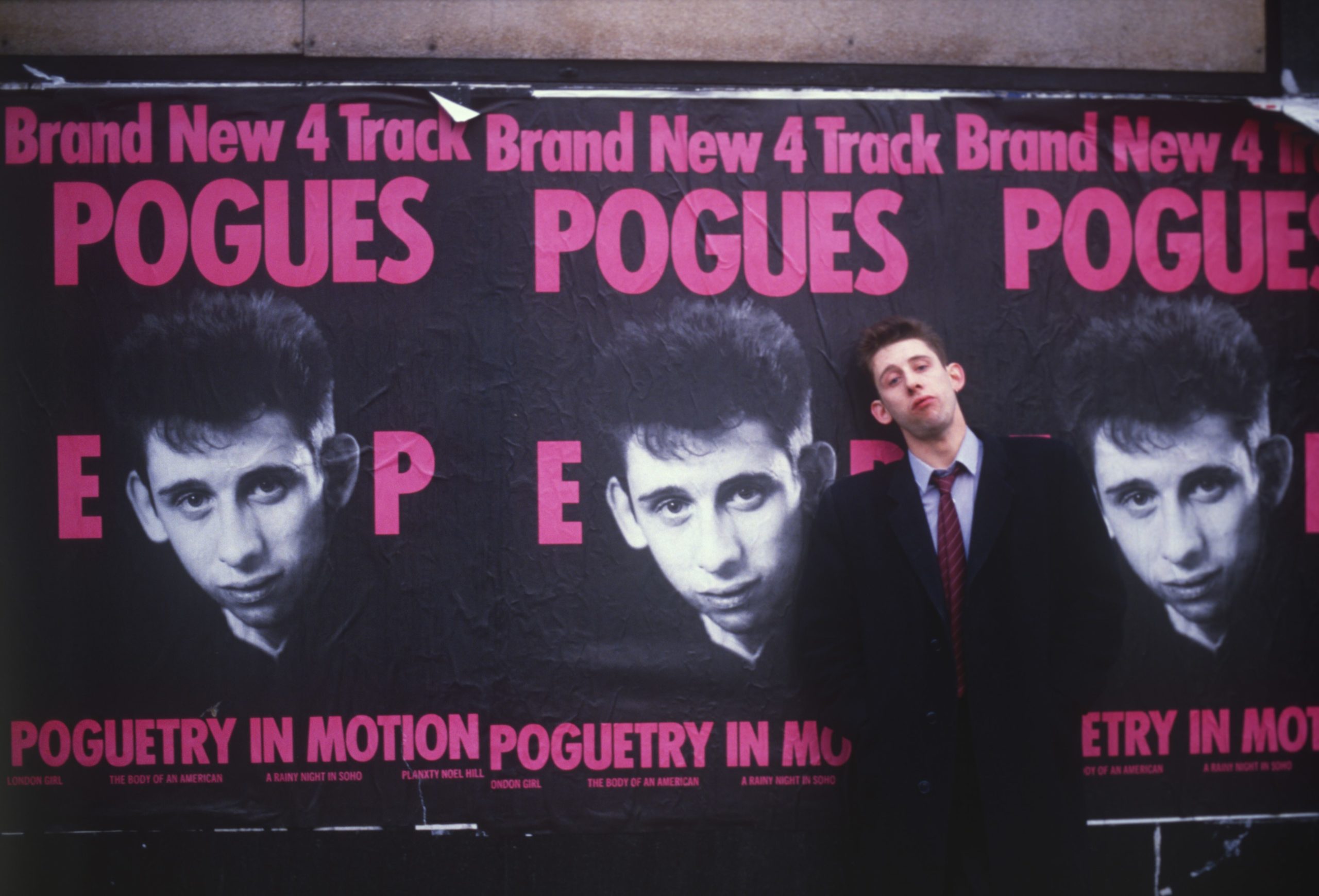

In his lifetime, Shane MacGowan could never have imagined any sort of appreciation in his name, let alone the sobriquets he was afforded at his death at the age of 65 on November 30. Renowned as he was for his prodigious drinking, his jagged smile, and an indecipherable cackle-croon that rivaled Tom Waits gargling razor blades, the Pogues frontman was a rebel, a roustabout, and something of a mess in the grand scheme of liquor-laced carousing and the traditions of fellow Irishmen Peter O’Toole and Richard Harris. MacGowan’s love of the drink was no secret to the British-born Irishman. “The most important thing to remember about drunks,” MacGowan once famously said, “is that drunks are far more intelligent than non-drunks—they spend a lot of time talking in pubs, unlike workaholics who concentrate on their careers and ambitions, who never develop their higher spiritual values, who never explore the insides of their head like a drunk does.”

RELATED: In Conversation: Julien Temple on Working with Shane MacGowan on His New Pogues Doc “Crock of Gold”

For all that, however, the writer and singer was a wastrel of the highest order, a lover of simple, yet beautifully rendered, loosely knitted language, and magic-realistic imagery conjuring the best and worst of the human condition, all set to music. MacGowan was possessed with a wrenching, charmingly poetic lyric-writing ability (and melody-writing, too—never forget he wrote many of The Pogues’ songs on his own) whose access to his Emerald Isle’s greatest and wordiest concerns (national pride bordering on nationalism, devout religiosity, ever-increasing social blight, booze, bloodied politics, his land’s history mythological and factual) made him a modern-day James Joyce.

MacGowan was, as his close friend and epic lyricist Nick Cave once said of him, an author who “made nightmares into living daylight,” before praising him upon his passing as “the greatest songwriter of his generation.” Ireland’s President Michael D. Higgins eulogized MacGowan as a national totem and “one of music’s greatest lyricists”—“So many of his songs would be perfectly crafted poems, if that would not have deprived us of the opportunity to hear him sing them. The genius of Shane’s contribution includes the fact that his songs capture within them, as Shane would put it, the measure of our dreams.” And just this morning, Jason Kelce, who reinterpreted The Pogues’ iconic Christmas song as “Fairytale of Philadelphia” with his brother Travis with the approval of MacGowan in his last-ever tweet, wrote that “Shane’s prowess as a singer, songwriter and poet was truly a gift to this world. He could make you feel what he was saying, attached his soul to his music.”

MacGowan was a man who could connect the palpably bloody pains of war to a veteran’s humble reminisces on “A Pair of Brown Eyes,” encapsulate the tortured entirety of pre-Christian Irish mythology on “The Sick Bed of Cúchulainn,” portray the most harrowing aspects of alcoholism as thrillingly rapturous on “Sally MacLennane,” make a mournful family wake into a jokey celebration with “The Body of an American,” turn blooming roses and warm summers into something bleak and bold for “Dark Streets of London,” and craft the rotted dialogue of a brutal verbal joust between lovers into the most listened-to Christmas song of the last three decades with “A Fairytale of New York,” his duet with another lost poet, Kirsty MacColl. “I’m just following the Irish tradition of songwriting, the Irish way of life, the human way of life,” he once said. “Cram as much pleasure into life, and rail against the pain you have to suffer as a result. Or scream and rant with the pain, and wait for it to be taken away with beautiful pleasure.”

I can recall interviewing MacGowan several times in person as a harrowing but welcome experience firm with patience for each other’s personality traits, and respect for the craft of writing. But while most of my MacGowan writings on The Pogues and The Popes are lost in the portals of magazines no-longer-online, my 2020 FLOOD interview with director Julien Temple for his MacGowan documentary Crock of Gold stands out as a forever favorite. Talking about the accolades afforded MacGowan with age, and how he was an unlikely uncomfortable recipient, Temple recalled a humbled, teary Shane in action. “He’s Shane MacGowan. It shouldn’t matter, all this wind being blown up his ass. These accolades are for an Elton John, not a Shane MacGowan. But he’s been through a hell of a lot to get there.”

And of the imagination and intelligence MacGowan’s writings held, Temple stated, “Shane is immersed in Irish history through his middle-class father, Dublin society, and prep schools…can be both generous and aggressive, and has made a real point of being Irish. John Lennon and Paul McCartney…you wouldn’t know they were Irish. The Beatles were not an Irish act. With Shane MacGowan, there is nothing but ‘I am London Irish. My roots are Irish. I’m going to give you Ireland. And I’m proud of it.’”

Let’s give the last words of this appreciation to Shane. As a man with as many addictions as he had dashing, robust, and colorful ways to write it all down, it was assumed that MacGowan was a nihilist on a death trip. To me and many others, the bad was the good and he held a lust for life and letters like no other. “If there’s someone who wants a lot more of life,” he once told the New York Times, “it’s me.”

Cheers, mate. FL