Don Draper, like America, went to war and came back with two identities.

Post-war America dealt with its newfound superpower status by dividing. Half of society embraced the surge of industry and journeyed to new suburbs with steadily growing families. The other half, disillusioned and restless, denied marching orders towards the Cold War and retreated inward on an endless search of self and identity. Commerce and art. John Wayne and Marlon Brando. Culture and counter-culture.

Don Draper appears in Mad Men‘s pilot episode, “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” / photo by Craig Blankenhorn/AMC

Don Draper (Jon Hamm) began life as Dick Whitman, a traumatized child of poverty, and left the Korean War assuming the dog tags of a lieutenant he inadvertently killed. The new Draper entered the booming workforce with an alliterative name reminiscent of comic book heroes and a strong ambition-chin combo to match. As a creative director at a New York advertising agency, Draper funneled a tragic upbringing common among artists into fuel for America’s highest-paying, lowest-regarded creativity. Advertising is society’s most anonymous art form for all its visibility—a dichotomy that reflects the paradox of Don Draper’s secret past and head-turning presence.

Through seven seasons, Draper exhibited a unique knack for crossing between the mainstream culture and alternative counter-culture of the 1960s. His suit screams “enemy” to the early-decade Beat scene, yet people can’t help but talk to him; he speaks the worldwide language of struggle, and everyone wants to be heard.

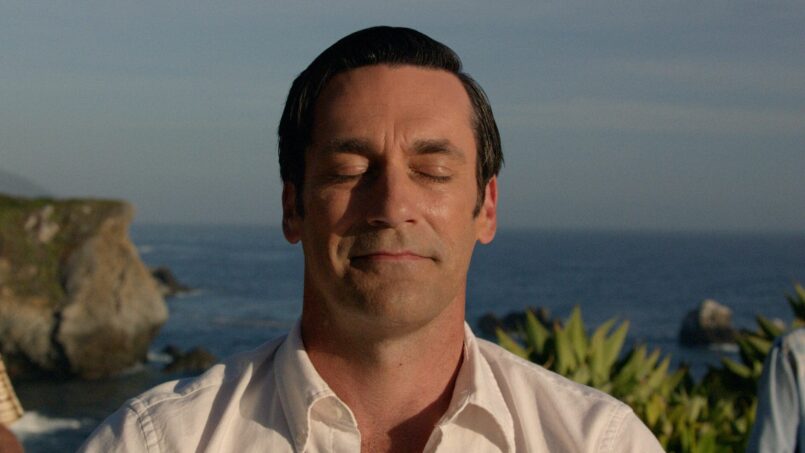

Don Draper zens out in Mad Men‘s final episode, “Person to Person”

He enters the era’s Bohemia for many things: sex, escape, inspiration, oblivion. It exposes him to reflections of consequence and mortality his profession works to cushion. His alcoholism segued from high-functioning to devastating. His Beat mistress, Midge (Rosemarie DeWitt), returns mid-series, ravaged by addiction, to sell her art (drugs are rare products that don’t need advertising). His attempts to reach rock-and-roll personalities (most memorably The Rolling Stones at their peak counter-cultural status) bring him staring into the abyss of the generation gap, and consequently the premature death of irrelevance.

By the Mad Men series finale, “Person to Person,” Don has fallen from New York white-collar society and staggered west into California’s hippie movement; his crisis ballooned from “identity” to full-blown “existential.” A spiritual retreat offers Don another fresh start, a re-established détente for his two identities, and that most crucial of things in advertising: a new idea. The final transition from Don’s mid-meditation smile to the world-famous Coca-Cola commercial, “Hilltop,” implies that Don left the counter-culture once again with a war story and a billion-dollar concept.

“Hilltop” co-opts the hippie movement to depict people from all walks of life gathered in song, each singer holding a Coke. The commercial is the ultimate fusion of culture and counter-culture: a well-intended message and a marketing imperative hand-in-hand. The gentle harmony of the ad is a lullaby to sleep for a beloved show and a complex character, and perhaps the warring twins of America’s culture. It’s death-fearing Don Draper’s bid for immortality. More importantly, it’s his ultimate reassurance to the culture and himself: there is one world, no matter how divided. FL