There is no conceptualist more capable of utilizing the free-jazz flow of the Beat Generation and the DIY ethos of graffiti than Mark Mothersbaugh. And the human eye—fragile or God-like, evolved or de-evolved—has long been a focus of his visual art process. The teenaged Kent State student who learned screenprinting before the college’s infamous massacre—certainly before befriending Gerard Casale and forming Devo—had been making works of art ever since he was pronounced legally blind during his childhood. After COVID hit and he was placed in Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s ICU for 18 days, a bizarre hospital accident rendered him completely blind in one eye.

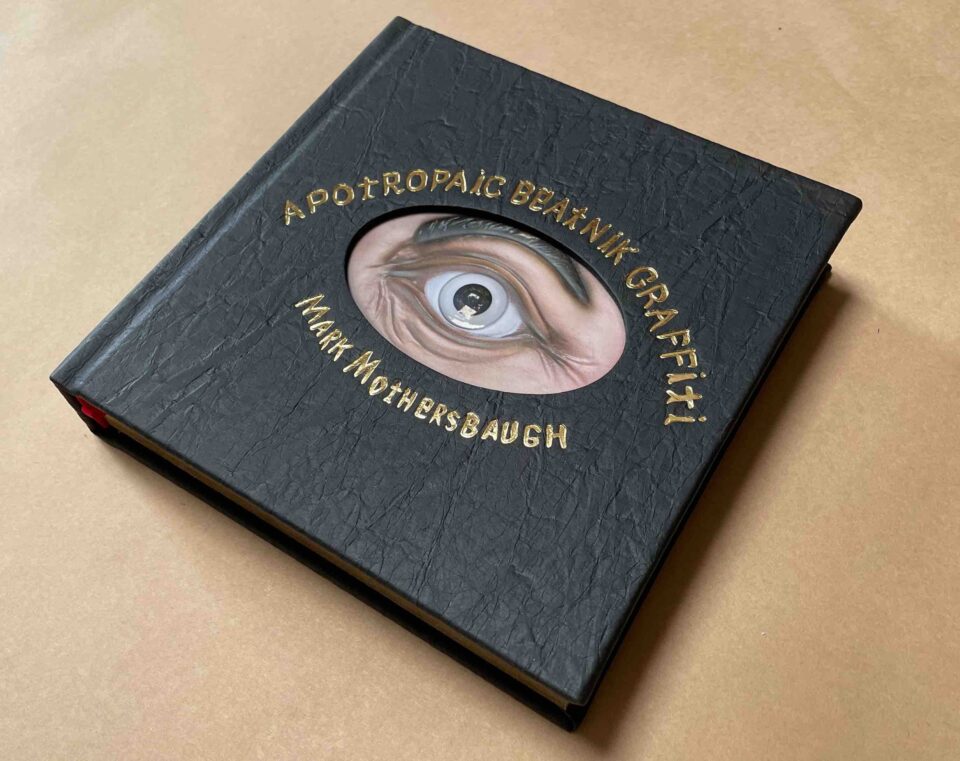

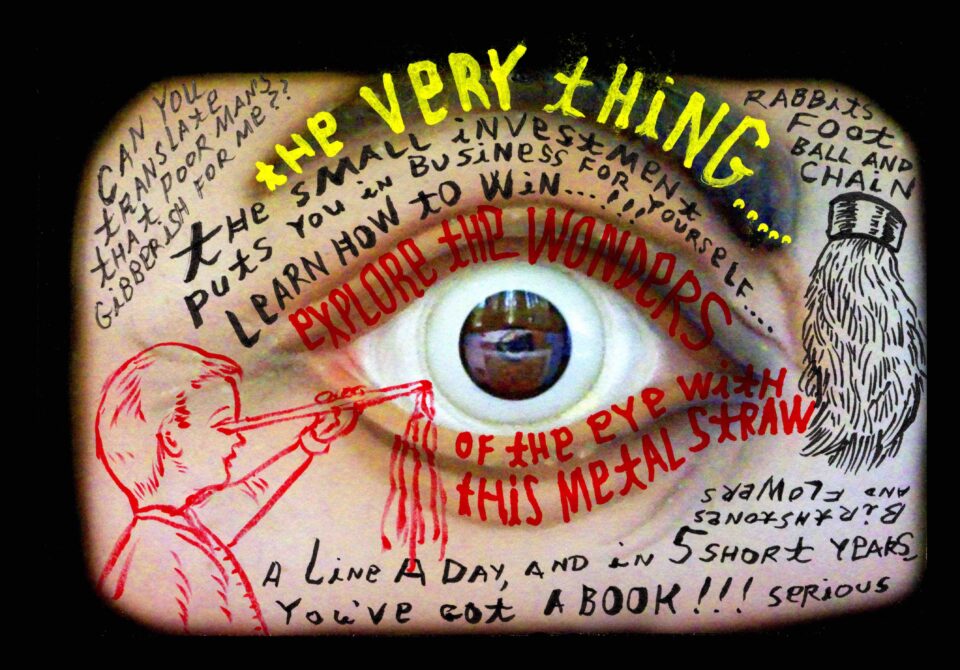

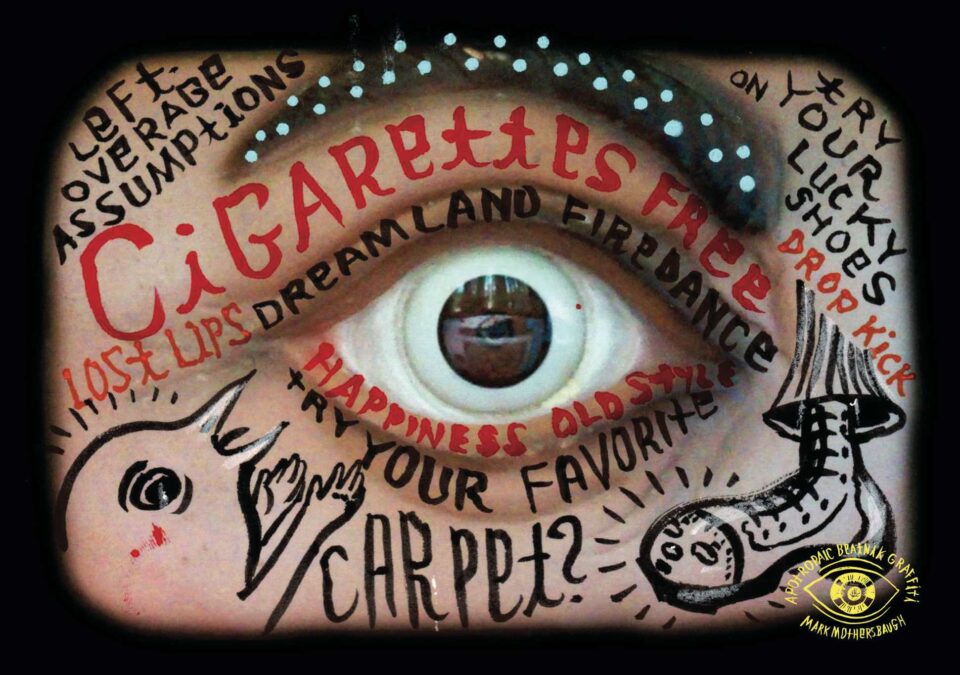

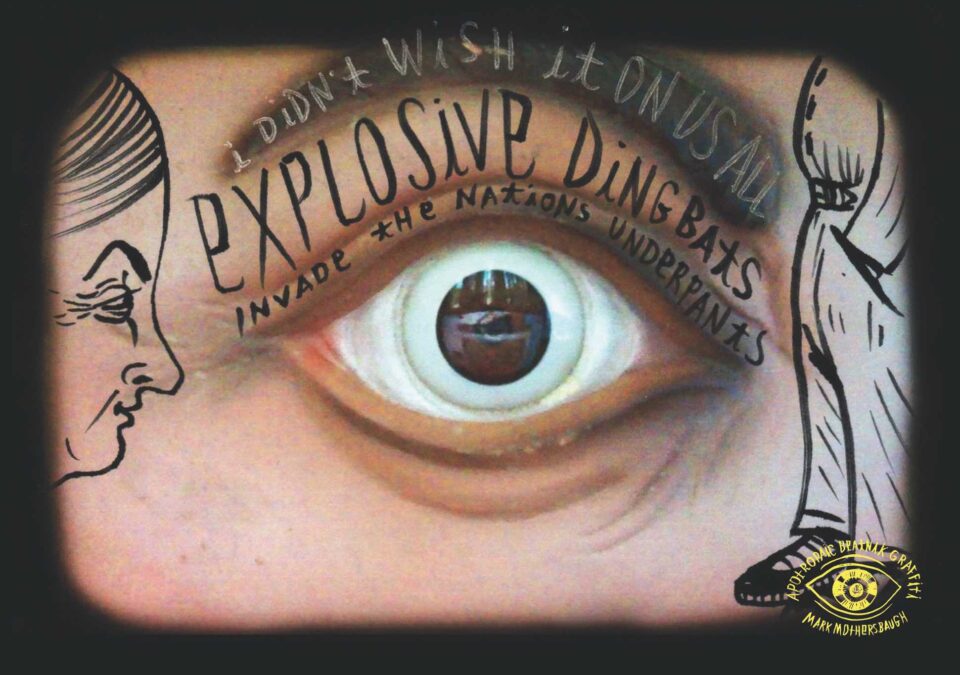

For better or worse, everything begins and ends with the eye for Mothersbaugh—the damaged eyes of his youth and his present day, the protective apotropaic eyes he found in botánicas when he got to California during Devo’s punk-era start, the eyes that filled religious and scientific pamphlets on his road to curating hundreds of volumes of his own optical art. With that, there’s Mothersbaugh’s new book of eye-centric paintings lined with stream-of-conscious poetic rantings and random cartoon imagery, Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti. Born from his collection of commercial “mail art” that he collected in over 700 archival installments, the book focuses on five of its volumes that Motherbaugh came to realize had been a source of Devo’s lyrics, album titles, and cover graphics, along with working as the basis of larger, more experimental art pieces.

On a brief break from Devo’s 50th anniversary tour—and shortly after discussing that and all things else Devo-related—Mothersbaugh spoke to me again from his LA studio about the influence of the Beat poets, his first corrective lenses, and the eyes that make up Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti.

At the top of Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti you credit Beat poetry. I know William S. Burroughs was something of an influence in Devo’s life and aesthetic, but I never caught on that they played such a formidable role in your art.

The Beats were the first intellectual artists of the post–atomic bomb era. They were critical of the human race, their activities on the planet. I had many bones to pick with mankind during my life in Akron, so I gravitated to the Beats. I liked their expansive poetry and its connection to the English language. In a way, that connection to the Beats matched with other things I was interested in, such as the rantings of homeless people or Christians speaking in tongues.

Pentecostalists, the Assembly of God.

When I was in my teens, I’d gone to one of their meetings by accident. My girlfriend and I got asked to come to a free dinner at this church, so we ate and watched as the people there practiced speaking in tongues. One person would speak gibberish and the next person would interpret it—and their interpretations were always Biblical, and had a lot to do with the end of the world. I was shocked and pleased.

“My mom had one question when Devo moved out to Los Angeles: ‘Honey, are you getting enough to eat?’”

How did your parents help you get into art-making?

Though it was not even a remote dream for him, I think my dad would’ve loved to have been an artist. He was like Timothy Leary to me, another of the most optimistic people I knew. My father believed we could do anything we wanted, so when I chose music and art, he was like, “OK.” They were both very supportive. My dad, on a fluke, got cast in Chuck Statler’s [Devo short film] Truth About De-Evolution and wanted to tour with us. I wish I would’ve had him come. He did wind up writing a few of our lyrics, and wound up in a few Devo videos. My mom had one question when Devo moved out to Los Angeles: “Honey, are you getting enough to eat?” I’m lucky for their support.

Was one of your parents more tasked than the other with helping you take care of your vision as a child when you realized it was beginning to fail?

My mom had pretty bad vision, so she paid more attention. But it was a teacher during the last month of second grade who pushed my parents to get me a more detailed eye exam and found me legally blind. My dad was embarrassed—he thought I was really intense instead of having eye problems. I used to have to get right in front of your face to see you if I heard your voice. Glasses, then, became my saving grace.

How did further damaging your eye during a hospital stay at the beginning of COVID shift an already fractured field of vision?

There are times when having stereo vision is helpful when you’re writing, drawing, or putting words on paper. You feel more confident doing smaller pieces of art. It’s ironic. The eye that’s damaged sees things very close to what they looked like when I was a kid having extreme myopia. It’s back to the fog, glints of light as if shining off the silver bumper of a car.

What can you tell me about these huge red collections that you’ve gathered together your whole life and how a portion of them forged Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti?

They could’ve been just sketchbooks. Brian Eno does the same thing: one same-sized, black moleskin notebook that he carries everywhere. I’d love to see a collection of those displayed—he never talks about them. When we recorded Are We Not Men? with him and saw his sketchbook, that made me feel closer to him. I like people who have diaries, sketchbooks, photo collections. Now, everybody does it. Often it’s parents with photobooks of their children’s birthday, or their own personal stories, but they’re important. These books collect crucial information.

“I like people who have diaries, sketchbooks, photo collections. These books collect crucial information.”

And several of those red books revealed how interested in the eye you’d become.

Yes, it was a form of tunnel vision where I was motivated to make these cards that had these eyes on them—like 700 to 800 eyes culled from science, medical, and religious work. That interest in religion and its connection to de-evolution is what drove me when I came out to California in 1977. Latin shops—botánicas—in LA were so amazing to me with their rows of tinctures, elixirs, and labels that read “Stop your husband from cheating,” or “Help yourself from drinking.” And there were these impressive glass apotropaic eyes that kept an eye on you while warding off evil eyes, things in the world that made you a victim of schadenfreude or jealousy or anger. Even something like mean bosses—you were protected.

The eyes were beautifully made, on plaster the size of a postcard with a piece of plastic glass painted in reverse, matte-colored, and realistically painted with the eyebrow in place and fleshy eyelids. The eye in the middle gave it this strikingly realistic look. I loved those and kept them around my studio all the time. In the 1970s I started using these oversized printers that would print on cardstock. Instead of using postcards or index cards that I had to flip over, I could buy rolls of archival paper and prep them with anything—scan a photograph of my skin, or multiples of those eyes. I would write words on them, maybe fragments of conversations I heard in person or during the news. I’d add artwork on each of the eyes as well—I still do them. Maybe I do them every day. They protect you from evildoers, people with bad intentions.

The free-flowing texts on so many of the eye cards perhaps stem from your first love of the Beats and their spontaneous poetry.

I got to Kent State too late to be part of those earliest happenings, but Jerry Casale and Bob Lewis were writing poetry—acid beatnik poetry is what it sounded like to me—and when we became immersed in devolution, that became another way to think about things.

The red books are the height of the art of curation, that thing that makes Apotropaic Beatnik Graffiti both singular to you and universal for the viewer. Along with the cartoon eyes you found in religious and science pamphlets and the plastic-and-plaster eyes you purchased in LA botanicas, the entire picture becomes clear.

I’ve had bad dreams where someone crying in black veils allows all of my red books to become landfill. I’m laying at the bottom of a heap at a garbage dump with trucks backing up and creating higher layers of garbage every day. I see all of my red books come tumbling down out of this truck. One of them falls open next to me, randomly, and all I can think is that they served their purpose—they kept me amused while I was alive. Those bad dreams motivated me to want to preserve and highlight these images in books. FL