Max Roach

We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite [Reissue]

CANDID

Though he was a classically trained percussionist, an avatar of the artist-owning label movement, and a free improvisational giant, few in the bebop scene of the 1950s would’ve considered drummer-composer Max Roach to be a racial revolutionary. A civil rights activist (albeit a quiet one), the accidental death of two of his cherished band members in 1956 shifted Roach’s perspective, heightened his awareness of time’s fickle nature, and made him more intolerant when it came to the plight of Black America. Something changed in Roach. He became bleak, and his music more resistant.

This approach crystallized in 1960, beginning with the album We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, a sharp castigation of global racism and the hoodlums who perpetrate it. This was the year in which Roach would explode in an intellectual and improvisational display of pro-Black sentiment. Along with recording on jazz pianist Randy Weston’s seminal Uhuru Afrika in 1960, Roach also joined up with his friend Charles Mingus to protest the Newport Jazz Festival and his push for a more inclusive (racially and sonically) booking policy in the face of the fest’s increasingly conservative policies. The resulting 1961 album titled Newport Rebels—along with We Insist!, both of which see re-releases via Candid Records this month—remains one of the finest, most abstract expressions of what it means to confront racial injustice in jazz or any other genre.

Along with organizing an alt-Newport fest, Mingus and Roach formed The Jazz Artist Guild with whom they recorded a mix of gently applied free jazz and hard bop that, though ferocious in places (“Mysterious Blues,” with angular alto sax and chill trombonist Jimmy Knepper, is particularly haunting), is surprisingly conventional in its melodicism. That’s not a diss—its sensitivity and desire for change is wrapped in the soulful brass work of trumpeter Roy Eldridge, pianist Tommy Flanagan, and drummer Philly Joe Jones. And hearing vocalist Abbey Lincoln rip through “Tain’t Nobody's Bizness If I Do” is one of that trad-jazz track’s haughtiest renditions.

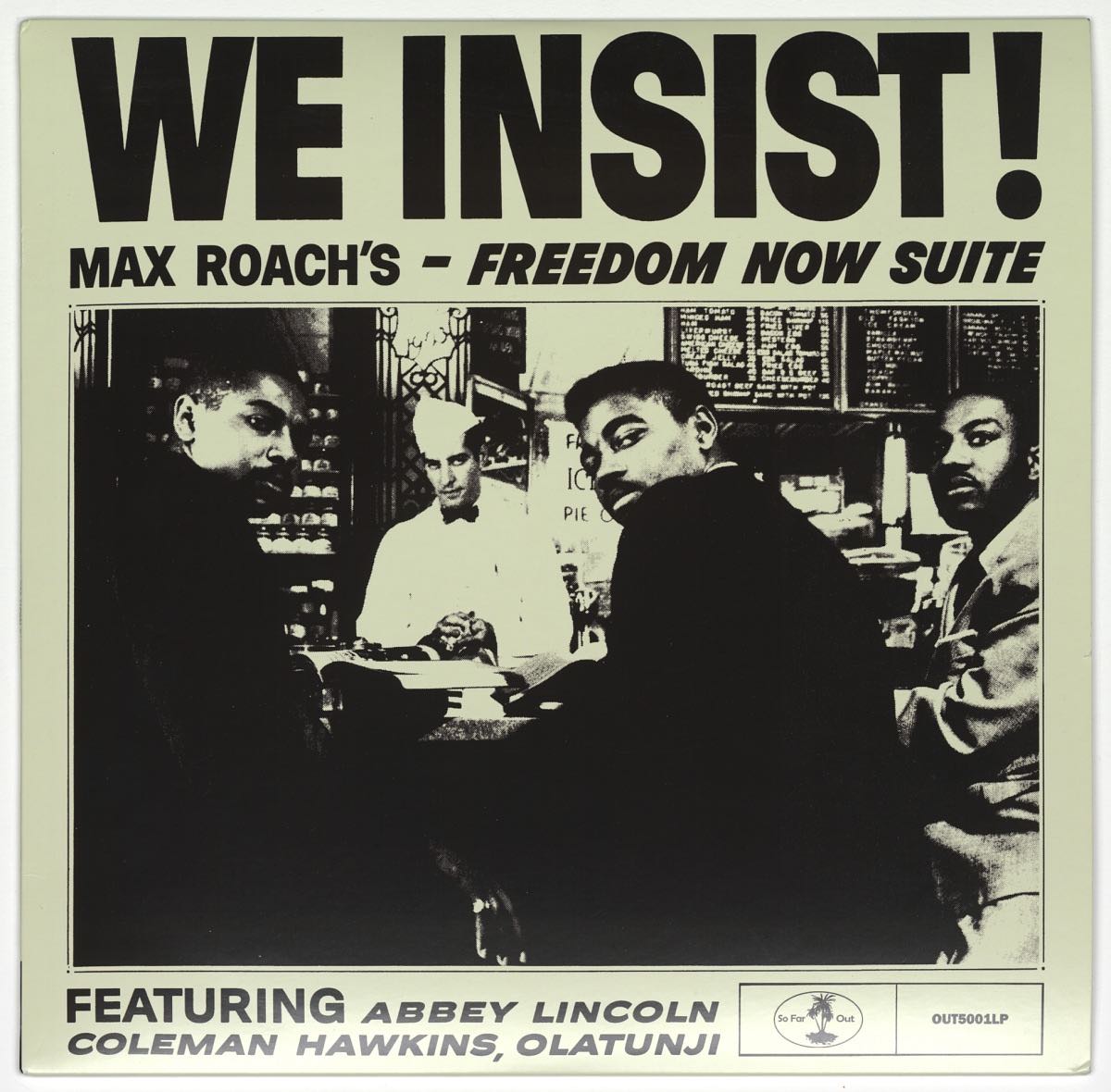

What Roach, his then-wife Lincoln, and author-lyricist Oscar Brown, Jr. had in store for the vehemence and ire of We Insist!, however, changed the game for how music could express rage, and certainly set the table for the soon-burgeoning politicized folk sound. From its stark title font and black-and-white cover (three Black men at a lunch counter with a white restaurant worker, all looking directly into the camera) through to its often-spare (“Driva’ Man” and its snare-only accompaniment), short (36 minutes), but unsparing sound, Roach and company (including tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and conguero Babatunde Olatunji) make no bones about cutting to the heart of what makes racist America tick.

Taking its structural cues from Roach’s classical background, this is an avant-garde Black operatic suite torn into bite-sized bits—the Civil War setting of “Driva’ Man” and “Freedom Day” (both with lyrics by Brown, Jr.), “Triptych” and its focus on current struggles and racial divides, a final movement in “All Africa” and “Tears for Johannesburg” that seeks equality for the motherland—and rendered with passion. In particular, hearing vocalist Lincoln and trumpeter Booker Little tear into the hardcore bop of “Freedom Day” with spite and sorrow; the abstract, free-verse (and often wordless) frenetic soul of husband and wife alone on “Triptych”; the manner in which Olatunji lifts Lincoln’s voice to new heights on “All Africa”; and the blues-based blend of Latin, African, classical, and modal jazz melody on “Tears for Johannesburg” played with ferocious spontaneity—my mouth drops every time I hear it.