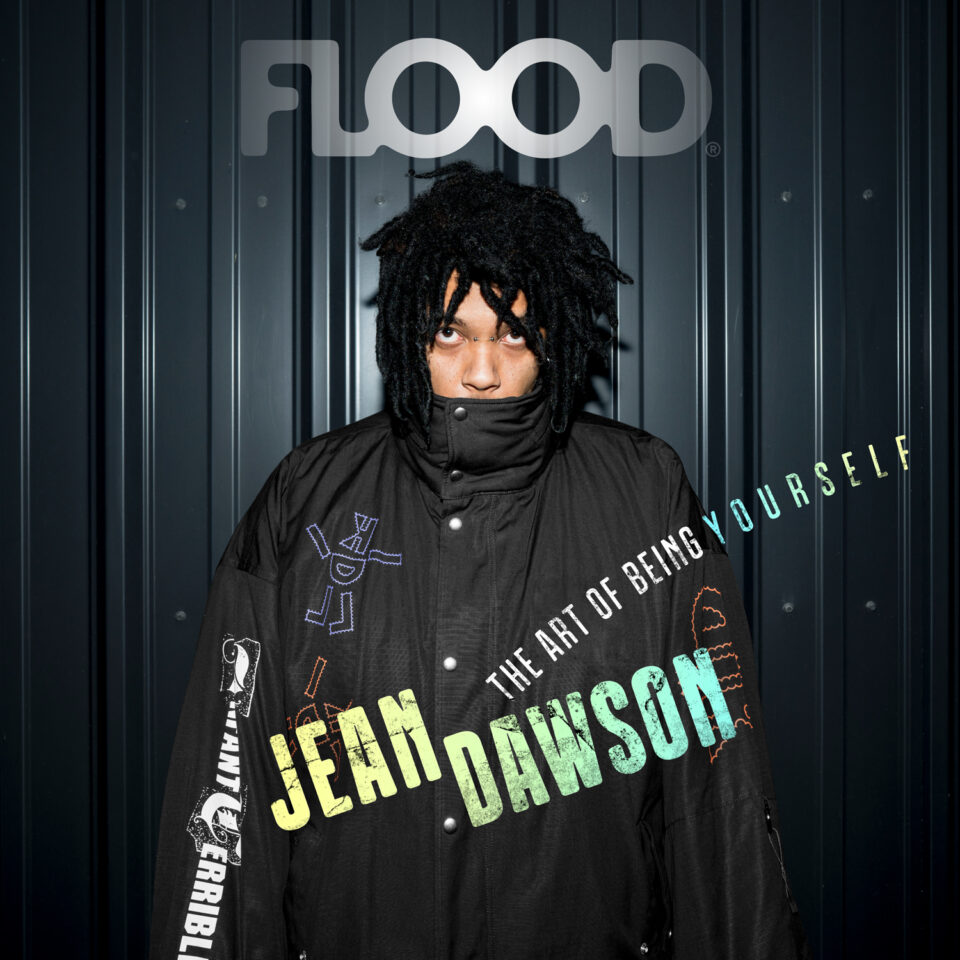

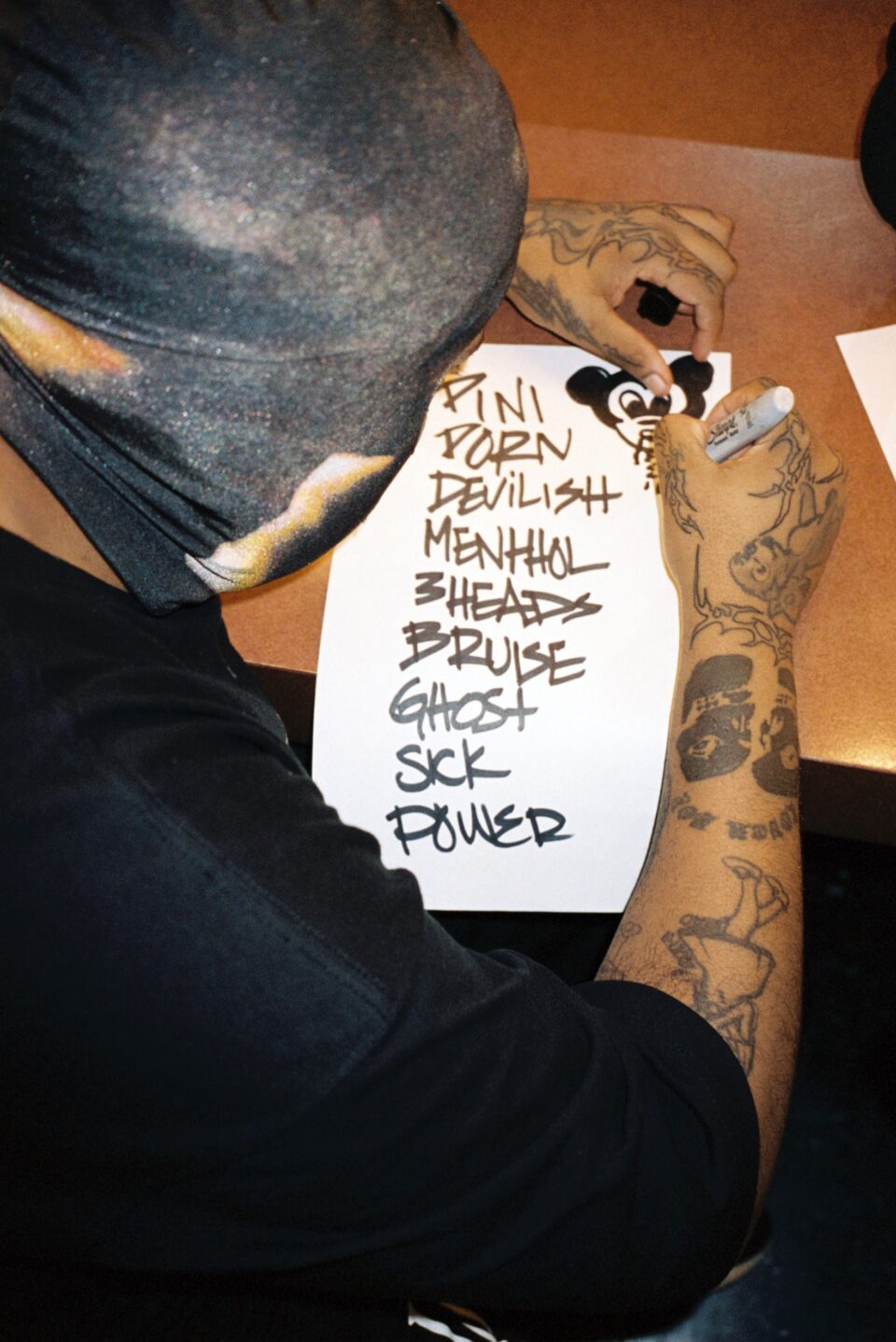

On December 22 of last year, Jean Dawson posted a photo to his Instagram Story for his 28th birthday. The picture, according to its caption, was a surprise Dawson woke up to, and shows a life-sized Mickey Mouse figurine (which is about two to three feet, in case the people in costume at Disney resorts have distorted that) dressed in a Santa outfit and holding a bunch of balloons designed to look like Poké Balls. He’s surrounded by a wealth of presents wrapped in silver or black paper, each one bearing a different nickname, creating a definitive list of everything he’s called. It’s an extensive selection: Bruise Boy, Daze, Nightmare, Him, David, Boohoo, Blame by Me, Brother, Baby Spooky, Twin, Arcoiris, Ghost, Phoenix, Toshi, Toto, Human Boy, Jean, Parlay, Hermano.

People already familiar with the LA-based musician and visual artist should already recognize a few of those. David Sanders is his birth name. Phoenix and Nightmare are both characters he assumed on a couple of EPs he released last year, the first two parts of a trilogy that he said in a recent interview showcase three different “hyper-aestheticized” sides of himself. There’s the name—one he reveals off the record—his close family call him, and some of the monikers (Daze, Toshi) he used to release music before settling on Jean Dawson with the unveiling of 2019’s Bad Sports LP.

As for the rest, that’s for Jean and those close to him to know. But it raises an interesting question: Who exactly is Jean Dawson? And how much difference is there between art and artist, between the person who sings his songs and the characters that inhabit them? And how far apart is the distance between the mysterious—if not even mythical—persona Dawson presents himself as online and the real him? The answer, of course, is both simple and complex. Born in 1995 to an African-American father and a Mexican mother, Dawson has straddled different identities from the beginning, both in his life and his music. Half-American and half-Mexican, he grew up in both Tijuana, Mexico and Spring Valley, California, catching a bus from the former to the latter to go to school before moving to Los Angeles at 16. Twelve years later, he’s still there.

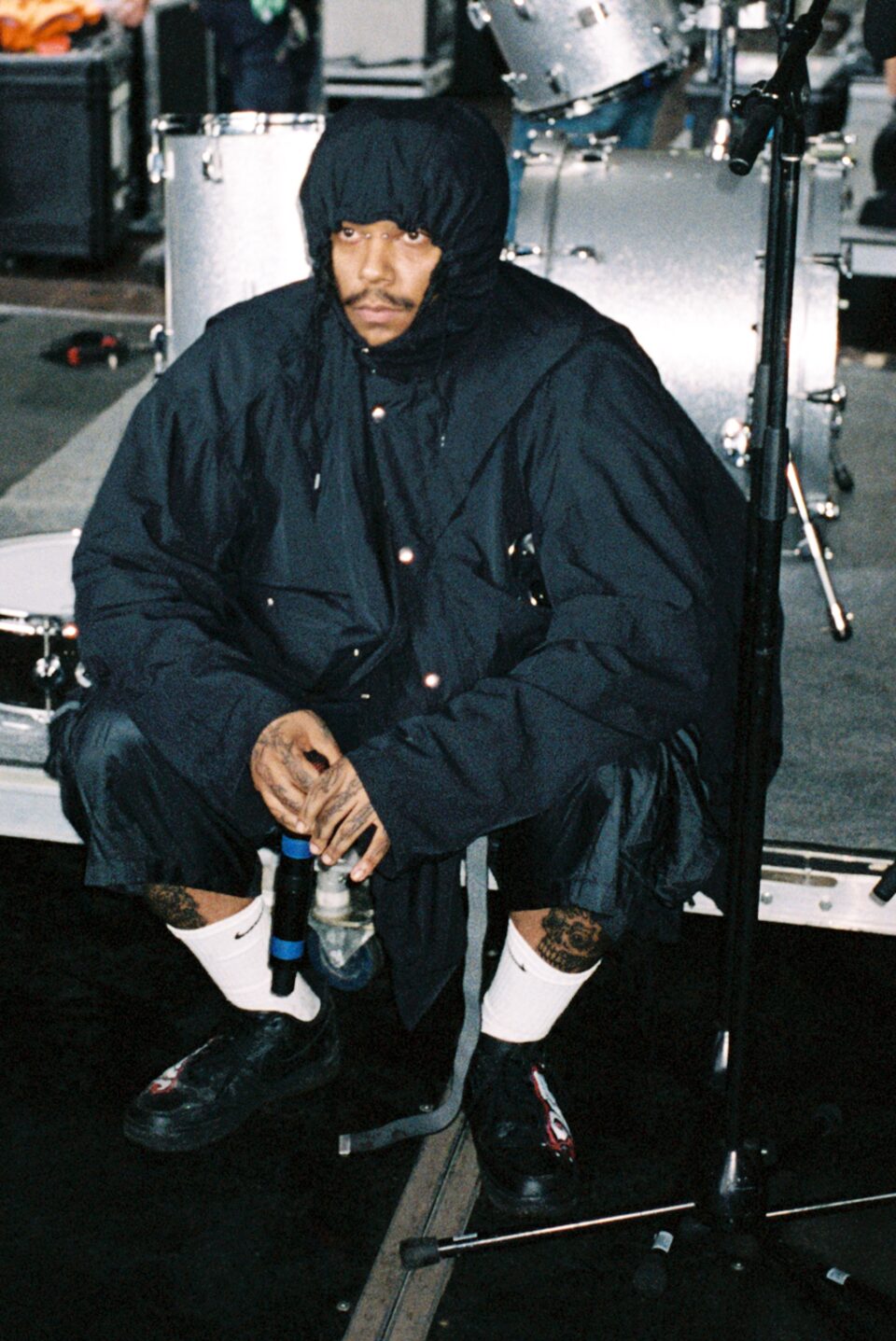

Today, a few weeks before his birthday, he’s outside his home, the LA sky above him unusually cloudy and gray. He walks in circles as he talks to me over Zoom, his restless pacing mirroring his restless mind as his words tumble out of his mouth in a surprisingly uninhibited fashion. It’s surprising because the persona Jean Dawson has cultivated for himself on social media—largely on Instagram, the platform where he seems most active—comes off as truly enigmatic, thanks to its incredibly stylized visuals and oblique/non-existent captions. His is a confident—at times almost arrogant—aesthetic, close-up images revealing the grills on his teeth while others obscure his face and employ the same techniques Marilyn Manson evoked in his Antichrist Superstar era to evoke the unwelcoming, rather hostile, character he turned out to be in real life.

In conversation, however, Dawson is anything but hostile. From the get-go, he’s incredibly open and authentic. As he walks around—revealing as he does a giant 12-foot skeleton his brother bought him for Halloween still guarding the house, which he says he might just leave there permanently—the conversation is more like a chat with an old friend than an interview. Indeed, just minutes in, he admits with surprising candor that he’s just come out of a seven-year relationship. “It was a good break-up, though,” he clarifies, his head tightly encased by the hood of his black hoodie, dreads splaying out and over his forehead and eyes as he walks. “It was very mutual. I hate being single though. It’s fucking gross.”

After a brief pause, Dawson continues, his words chasing his thoughts. It’s not that he’s speaking before he thinks, because his demeanor is an incredibly thoughtful one, but there’s no filter, no second-guessing whether he should say something or not. Set him off, and off he goes, indulging in long, philosophical, stream-of-consciousness monologues for which, at the end of the chat, he effusively apologizes. “I know transcribing this is going to fucking suck,” he’ll say, “because you’re going to be like, ‘I have to read all this fucking rambling again.”

“I’ve felt like I’ve died before, I’ve felt like this is like the second or third chance that I’ve gotten at living. I just chose to stop being afraid of an outcome I have no control over.”

In the present, he continues. “I think I’ve always been in relationships. Matter of fact, to a fault—since I was a child. I was with my mom like a week ago and we were talking about how girl-crazy I was. She was like, ‘Yeah, it started around first grade. You had two girlfriends that were twin sisters,’ and I was like, ‘Oh, dude, game was tight—what happened?!’ Now I just fucking go on dates and I’m like, ‘This is horrible.’ I just forget what to say and stuff. I had a date maybe a month back with an actor, and we’re sitting there and I’m like, ‘So what’s your life about besides being in films and stuff?’ And she was like ‘Honestly, it’s just movies and vibes.’ And I checked out immediately. I was just like, ‘Vibes?’ I felt old. I don’t know what that necessarily means.

“It really fucked me up,” he continues. “I was like, ‘Oh man, this sucks.’ And she was awesome. I just feel like I didn’t have the proper response needed to make that interaction viable, so I was just sitting there like, ‘Oh, so like, errr, what, what, errr, what else is, errr...’ I felt like I was fucking Morty from Rick and Morty, just stumbling on it all. And it’s not because I’m not a confident person. I’m pretty confident, but when I can’t draw out the truth from somebody very quickly, I get really over it. A lot of people have walls up for different reasons, but I’m very translucent. So when they ask me a question, I’ll tell them the entire truth really early on. Some people are like ‘Holy shit, this guy’s not afraid to tell me he wet the bed until he was five years old. That’s sick.’ Or it probably scares them and they’re like, ‘This guy’s done a lot of therapy.’”

There’s a lot to unpack from that one spontaneous outpouring of thought alone. With his Rick and Morty reference comes a Morty impression that’s so good it’s a shame it can’t be translated to the written word. Not only does that reveal his twisted sense of humor, but also his unabashed enthusiasm at being a self-defined geek for being very into video games, anime, and storytelling. At one point in the conversation he waxes lyrical about Lord Voldemort’s Horcruxes. Yet while his conversation is peppered with (often self-deprecating) humor, there’s a layer of Vantablack darkness lying underneath the surface. He doesn’t bring up Harry Potter to relay his love of the story, but to illustrate a point about his experience taking anti-depressants in an attempt to battle his persistent suicidal ideation.

“When I was like 21,” he remembers as part of another rambling recollection, “I wanted to kill myself every day for three to four months. That’s when I started my antidepressants, and it made my depression worse, which often tends to be the case in the beginning when you’re taking them—it makes your symptoms more dramatic. Around that period, I felt like I had died. And I say this in, really, a non-romantic way, because some of it sounds like, ‘Oh, you’re a troubled artist.’ But it had nothing to do with artistry, and everything to do with me not wanting to be alive. But I came out of that dark place and pulled myself to the other side, and now I’m very fucking good, and I’ve been good for a very long time.”

A wide smile spreads across his mouth, his dreads swaying across his face, before he continues. Freeze-frame it, and that smile is the epitome of pure happiness.

“I’ve done mad therapy and things are great,” he continues. “But during that time, I’d realized that this skin and this body that I possess, and this brain that’s the pilot of this flesh-bag that I am, is the only one I’m ever going to have. So every experience that I’ve gone through in my life is indicative of the person that I thus will become, and I stopped being ashamed of that. There was nothing worse than what I’ve already felt, so there’s nothing a person can say to me that I haven’t said to myself in the mirror. All that is to say I’ve felt like I’ve died before, I’ve felt like this is like the second or third chance that I’ve gotten at living. I just chose to stop being afraid of an outcome I have no control over.”

He goes on to detail the morning he realized, after months of taking them, that the pills had finally started working. Which is to say, he no longer wanted to take his own life. Every day that he’d been taking the pills, he’d woken up overflowing with adrenalin, his hands shaking, he says, the same way they do when you get in an altercation with someone. He’d moved back in with his mother to be under her wing, “because it was like, ‘If nobody watches over me, I’m 1,000,000 percent going to take my own life,’” he explains.

“I get the whole romanticism of the tortured artist, because for some people it is really the only resolution that they have outside of a permanent solution to an impermanent problem.”

It was a long and arduous process, and one that very much got worse before it got better. “I’m just fucking lucky enough that I had all of the negative side effects,” he says sarcastically of his SSRI, “one being an increased depression of, like, 1,000 percent. So for the first time in my life, I felt what people were talking about when it came to depression. And I was like, ‘Holy shit, this is what you guys feel? This is fucked up!’ You think you’re never going to escape it—it’s like a wet blanket on your shoulder. It’s, like, sadness, nothingness, just death incarnate.”

One day, however, he did escape it. “That morning,” he recalls, “everything felt really calm. I didn’t feel anything alarming. I go outside to have my morning fucking cigarette, and then I look up and the sky is fucking blue! I live in California—the sky is always blue. But for three months, I never acknowledged how blue the sky was. And I was like, ‘Holy shit, is it always this fucking beautiful? What is going on?’ And then I’m like, ‘Wait, am I happy right now? Wait, what?’”

It wasn’t quite that straightforward, and there were a few more bumps in the road before getting to how he feels now, but that was the first breakthrough. And it was at this point that Dawson was able to finally focus on writing music again. He’d already begun and then given up on what would become his first release with the Jean Dawson moniker, Bad Sports, which is another way in which Dawson refutes the idea of the tortured artist stereotype—he simply couldn’t finish that record while feeling so existentially low. “I was probably about 40 percent done with it,” he remembers. “It was while I was in college, and then I left and I was like, ‘Well, I’m not going to finish that project because I feel like shit.’ You couldn’t ask me to write a fucking sentence, let alone a song, because of where I was at. I get the whole romanticism of the tortured artist, because for some people it is really the only resolution that they have outside of a permanent solution to an impermanent problem—which is what I was essentially dealing with.

“The reasons why I didn’t commit suicide—for one, I was terrified, and two, I knew that such a permanent solution to something that was in passing wasn’t the answer. But it did feel like the answer for a long time. You know, Kurt Cobain is one of my favorite artists of all time, and people can imagine the pain that you have to go through in order to take your life. It’s an unimaginable amount of pain. Some people think it’s cowardice, and I’m like, ‘Well, I don’t know. You can’t ask me to bungee jump, let alone throw myself off a building without any cause.’ So I don’t know if it’s cowardice. I just think that it’s misunderstood. For me, in that time period, writing music wasn’t even something that I could fathom. But when I got out of it, it let me realize why I needed to write music.”

“In that time period, writing music wasn’t even something that I could fathom. But when I got out of it, it let me realize why I needed to write music.”

That’s what he’s been doing ever since, mixing grunge and other alt-rock subgenres with hip-hop to create something that truly represents and captures the many facets of not just who he is, but where he comes from and where he wants to go, whether that’s a beautiful folk song or something more abrasive. His latest EP, Boohoo—released at the start of March, but not part of the trilogy—leans even more heavily into that. Intended as an overture to an album coming out later this year, it not only contains some classical elements, but also Dawson’s first Spanish-language track, “Divino Desmadre.” Each of the three songs probes a little bit deeper into the distinct facets of his personality—expanding his sound (and, by extension, his self-expression) while simultaneously honing in on his identity. In other words: moving away from who he was to more fully become who he is—growing, adapting, evolving as a human and artist hand in hand, reaching into, extrapolating, and then combining all those different but equally important parts of himself.

He’s been engaged in that multi-faceted approach on a staunchly DIY basis, too. Not because he hasn’t had offers from labels (he has—and good ones, too, by all accounts), but because maintaining complete creative control and freedom is paramount. Since Bad Sports, he’s released two full-length LPs, 2020’s Pixel Bath and its 2022 follow-up CHAOS NOW*, plus the three EPs. He’s supported both Interpol and Trippie Redd, and played the 2023 iteration of the emo-nostalgia festival When We Were Young. There’s also the beautifully haunting “NO SZNS,” a song that features vocals from R&B icon SZA, which certainly raised Dawson’s profile, if perhaps not quite as much as one might have imagined.

He kicked off 2024 by revealing tour dates with Lil Yachty—who’s recently also taken to deconstructing genre in a similar way to Dawson—before his name appeared on the track list for the buzzy Stop Making Sense covers compilation A24 will be releasing later this year. And then, last week, the day Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter was released, he tweeted a picture of its cover, announcing that he “Did some arrangement for this album” and confidently thanking her for his first GRAMMY either as a nod to the fact she’s never won one for Best Album, an indication that he feels she should (and will), or as just a huge tongue-in-cheek flex on Dawson’s part.

When talking to Jean Dawson, you never get the sense that he’s not being honest, that he’s not being himself. Not only does he think carefully about every question and every answer, but he’s genuine through and through. While his online persona might be mysterious and, like those EP characters, hyper-aestheticized, in person (or, at least, over video chat), he’s as sincere and friendly as can be. He’s proof you can be enigmatic and transparent, self-assured yet vulnerable, all at the same time—that they’re not mutually exclusive. That’s because he contains—as we all do—multitudes. There both is and isn’t a distinction between Jean Dawson and Bruise Boy and Daze and Nightmare and all the other names written on those birthday presents. All of these monikers are parts of him, and each part helps make him who he is as a whole. He’s all of them together as a whole, but, paradoxically, also each of them separately. They’re within him and he is, in turn, within them.

There is, however, one difference he’s keen to point out. “The relationship between Jean Dawson and David Sanders is a quite funny one,” says Dawson. Or Sanders. Or both. “David Sanders is the son of my father because [my father]’s the only person who calls me David. Then there’s my family name that everybody calls me, so that’s like a third character in this whole thing. And then Jean Dawson is the romanticized, hyper-aestheticized version of David Sanders and my other family name, which allows me to be like a method actor of sorts, where it’s like ‘This girl broke my heart, oh my god, I’m going to write a song,’ and, ‘This girl broke my heart, I’m going to go cry for a little bit.’ So David Sanders is going to go be upset and Jean Dawson is going to go write a song and make a video and express it.

“The relationship between Jean Dawson and David Sanders in my head is that there’s one guy that shares and there’s one guy that insulates.”

“If Da Vinci has two hands and he’s not ambidextrous, if he paints only with his right hand, that’s Da Vinci,” he concludes. “His left hand is who was being carried by his mother and his father, and who was being breastfed. Both hands are important, but they do different things. So the relationship between Jean Dawson and David Sanders in my head is that there’s one guy that shares and there’s one guy that insulates.”

Between the two of them is where Jean Dawson actually exists. He’s all of both and none of one. And while he knows what it’s like to feel dead, he is—perhaps against all odds—thankfully very much alive and kicking. While he is (and let’s hope that’s for a long time yet), he’s surely one of modern music’s most unique and intriguing and brilliant artists. And while that’s certainly something he should be proud of, he’s probably just as pleased that he’s found a loophole to receive a heap of birthday presents every year. FL