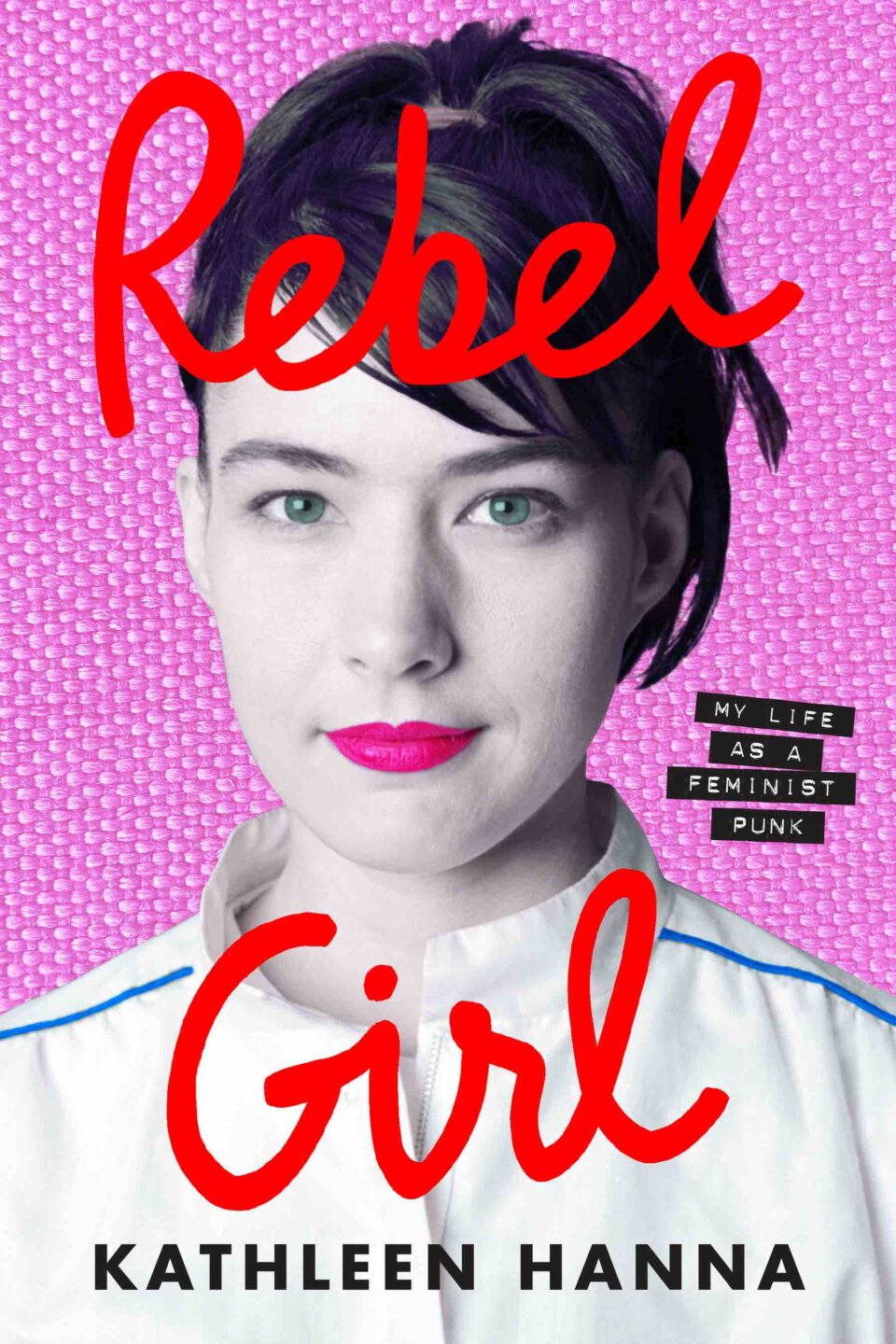

Kathleen Hanna is best known as the pull-no-punches leader of Bikini Kill, the influential group at the heart of riot grrrl’s push to imbue punk with a feminist message—which naturally triggered the everyday sexism embedded in American culture during the ’90s. Now, her memoir Rebel Girl serves as a chance for Hanna to tell her own story amid a narrative that’s often been portrayed from the outside looking in.

Yet this wasn’t the intention behind the book. Instead, it was meant to be a chance for Hanna to re-evaluate wounds from the trauma she faced throughout her life and to find a path toward a greater sense of joy. “I started needing to pack up my emotional and psychological damage, and the way I did it was to turn them into stories,” Hanna tells me over a video call. “I made narratives out of really uncomfortable situations and cried for the person they happened to, and finally admitted that they happened to me and not some character.”

Throughout Rebel Girl, Hanna shares her experiences as a victim of sexual assault and sexism—including revenge porn and slut-shaming—as well as a humiliating abortion experience. One passage describes how, having worked as a stripper when struggling to make ends meet, she attended a talk from the feminist speaker Andrea Dworkin who claimed that stripping was “a decision that will haunt you for the rest of your life.” Similar shaming experiences led Hanna to continue championing the more inclusive ideals she wanted to see in the world. Sexism was rife in her surroundings, from street harassment to the sense of exclusion women would feel from the supposedly progressive punk scene she was involved in. Hanna describes the fact that she needed to “have a reason to be there” when going to gigs, so would often take a camera with her as justification.

The counterculture ideals championed by Bikini Kill can now be found three decades later in mainstream pop. Olivia Rodrigo has spoken about the band’s influence and how it bled into 2023’s GUTS, while CHVRCHES’s Lauren Mayberry has cited Hanna as one of the reasons she’s determined to stand by her own convictions. Even if not influencing artists musically, there’s a legacy here in which riot grrrl assured women that their voices deserve to be heard in male-dominated spaces. “It’s great that we can have more nuanced conversations [now]. I welcome feminist ideas that challenge white supremacy to be out in the mainstream. We shouldn’t be afraid of them being watered down, because people are smart enough as viewers to go, ‘Wait, Olivia Rodrigo is donating to Planned Parenthood?’ and type it into the internet and learn more about what’s happening locally about abortion rights in their state.”

“I made narratives out of really uncomfortable situations and cried for the person they happened to, and finally admitted that they happened to me and not some character.”

Reading through Rebel Girl you get a feel for the feminist lineage that paved the way for the ideas Hanna and her bandmates poured into Bikini Kill. Whether it’s Angela Davis, Barbara Kruger, or Jenny Holzer, there’s plenty of activists, artists, and writers who provided a template for the inclusive feminism Bikini Kill always stumped for. “I’m always trying to pass on these kinds of influences and be part of a continuum—that’s the most satisfying part of being an artist to me,” Hanna says.

Eventually, Hanna realized that riot grrrl had become too closely associated with whiteness, which led to an increased effort from Bikini Kill to incorporate intersectional feminism within the message of the band and the wider scene. It’s an important distinction for Hanna that the message of the genre doesn’t get conflated with her being the poster girl. “People were thinking of me as this ‘super-feminist’—this superhero who just gets up there and is a badass. That’s not my experience of life. In general, societally, I don’t want to see intersectional feminism replaced by a ‘girls kick ass’ bumper sticker.”

At their shows, the band has made an effort to ensure that trans women feel included in their “girls to the front” mantra, while additionally printing flyers reminding audience members to not always assume someone’s gender. When it comes to the current punk and DIY scenes, Hanna feels as though marginalized groups will be the ones who lead them into the future. “I feel like a lot of issues about race and punk that have been raised forever can come to the fore now. On the surface, riot grrrl is now in the mainstream and I think that’s given us more space to grapple with the white supremacy that’s in the underground scene. The future is female, and I just feel like the future of punk is BIPOC people.”

Writing about women’s issues and feminism means that Bikini Kill’s work is treated with a certain degree of seriousness. But listen to “Carnival” or “White Boy,” the latter allowing a guy’s ignorance and misogyny to speak for itself before bubbling over into a hilariously sarcastic tirade from Hanna. Humor is a feature of her writing that’s extended well beyond her time in Bikini Kill—which ended its original run following the release of their second full-length Reject All American in 1996—over to Hanna’s turn-of-the-millennium synth-punk outfit Le Tigre, especially with their most widely known song “Deceptacon” with its brutally funny takedown of another songwriter (namely NOFX’s Fat Mike, who’d previously released a diss track of Hanna).

“Societally, I don’t want to see intersectional feminism replaced by a ‘girls kick ass’ bumper sticker.”

It’s easy to see Bikini Kill as antagonizers, when in reality they were just advocating for the world that they wanted to see. For Hanna, she didn’t want young women to go through what she’d experienced. Starting with the abuse she endured from her father, Rebel Girl follows pivotal events that shaped the author from young adulthood and beyond. At the height of Bikini Kill, Hanna was still touring with the band with all this untreated trauma while being under constant media scrutiny and earning nowhere near as much money as people assumed they were. It sparked an identity crisis, which Hanna has only been recovering from in recent years.

Her new memoir has been vital in exploring the conflict between her trauma and the life she’s lived since that period. “I certainly didn’t deserve to spend the rest of my life avoiding joy,” she writes in the prologue—which speaks to the extent to which trauma can cloud the past. “The book gets really heavy and I was like, ‘Oh god, I have to go back and remember happy moments.’ I would go to my office every day and sit and write every great thing that happened to me, and that was amazing. I realized how much the trauma was blocking out the sunshine. I’m waking up more grateful than I woke up before, because I’m not constantly being triggered by stuff that happened in my past.” FL