When director, producer, and film distributor Roger Corman passed away earlier this month, one repeated accolade came courtesy of his legendary taste for so-called “B-movie” cinema and his choice of then-young mavericks to craft them: a powerful list of moviemakers that included Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, James Cameron, Ron Howard, Joe Dante, and Francis Ford Coppola. From stock car races and bikini-filled beaches to monstrous sci-fi-scapes and high school mania, Corman and his talented underlings did it all.

My remembrance of Corman—whether as the distributor who brought foreign classics such as Fellini’s Amarcord to Stateside viewing or as the director behind the darkly colorful Poe-based House of Usher—is how rich and lustrous his films were, how unlike the definition of typical dippy B-movie fare this work wound up being. For an artist renowned for thrift, Corman’s output looked and sounded gorgeous, and it maintains its urgency: an art form unto itself.

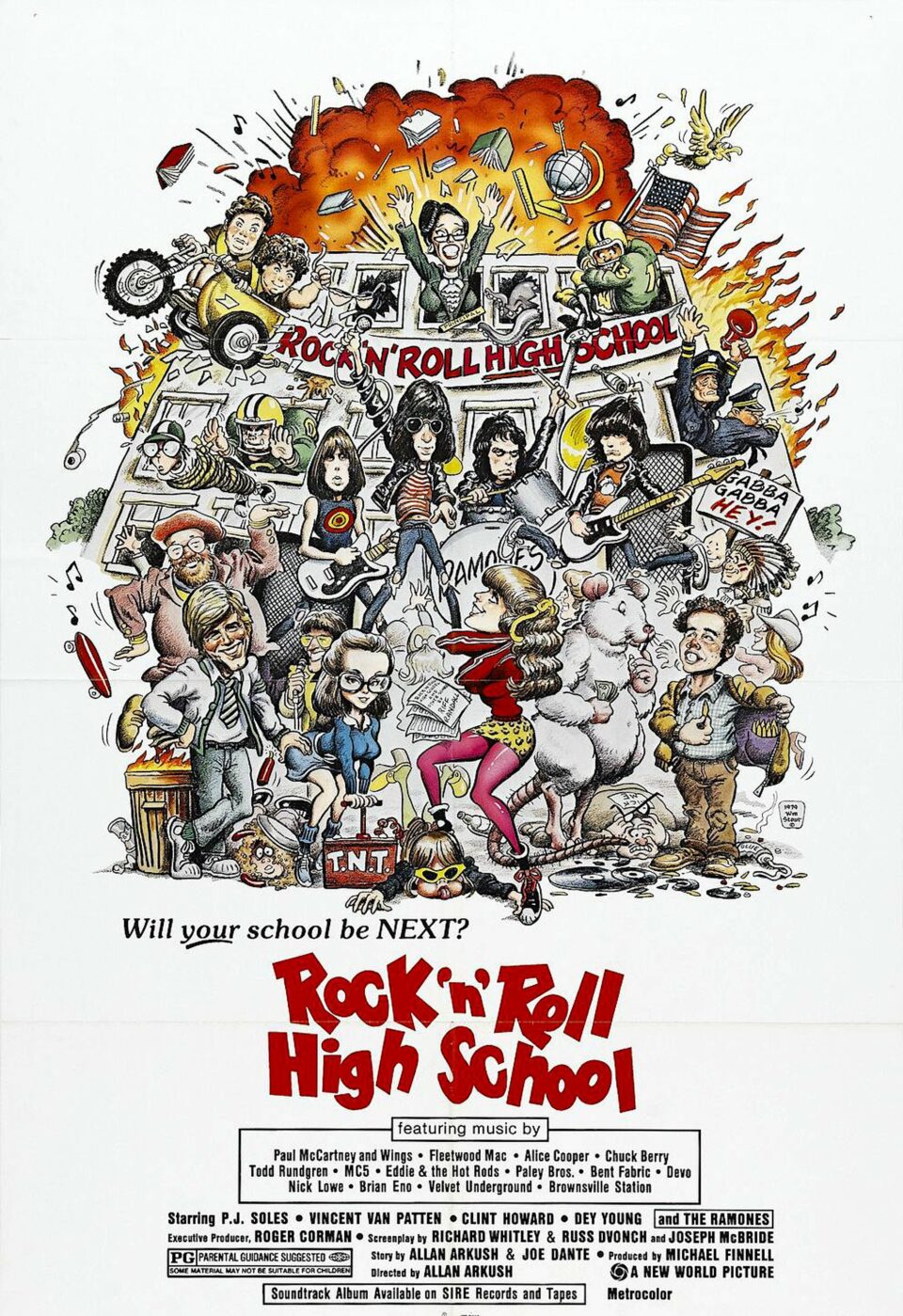

One of Corman’s most deeply entrenched and visionary collaborators, director-writer Allan Arkush, was the man behind 1979’s Rock ’n’ Roll High School, a punk-rock teen flick meant to seem exploitative, but one that came complete with subtle messages of female empowerment and the spirit of rebellious nonconformity, and a film that showed the connective tissue between art, rock, and commerce that hadn’t been witnessed since Arkush’s earliest days on the NYC gallery scene of Warhol and The Velvet Underground, and his work as stage manager and primary psychedelic visualist for the Fillmore East.

With all that, from its agency to its embrace of protest, Rock ’n’ Roll High School is the most relevantly modern—even postmodern—of Corman and Arkush’s collaborations. “One of the things that I think enabled Roger’s ability to reach out across the cultures is the fact that we were going through a period where aesthetics were either about high art or low art,” says Arkush from Los Angeles, prepping for his next gig: a professorial position at the American Film Institute. “Roger showed that both sides are worthy of study—something that’s immediately connected to Pop Art.” Arkush here begins to tie together the disparate elements that united the work of Warhol, Lichtenstein, and other giants of the painterly Pop Arts to the cinema of filmmaker-animator Frank Tashlin and comedian-auteur Jerry Lewis. “Those are all of the same piece that came to inspire me through the visual style that I used on Rock ’n’ Roll High School, and the film I made before that with Joe Dante, Hollywood Boulevard.”

Recalling his start in the film business working in the in-house trailer, post-production, and color-correction department of Corman's New World Pictures, Arkush believed this aided him in creating a personal aesthetic. “Our choices came from the postmodern, Pop Art sensibility that you’re talking about. We didn’t realize that. We just came to that. We were trying to let you know that these women in prison movies or car chase films were to be dealt with on their own terms with a gimlet eye.”

“We were going through a period where aesthetics were either about high art or low art. Roger showed that both sides are worthy of study—something that’s immediately connected to Pop Art.”

Arkush looks to Corman’s work with an up-and-coming group of friends (himself included) who attended Scorsese’s NYU class, American Cinema (“All about the auteur theory”), and made up the Move Orgy, a series of short films that played between bands gigging at the Fillmore East such as The Who and the Grateful Dead. “We were re-contextualizing culture at the Fillmore because we didn’t want the kids in the audience to sit in the dark while the bands on stage changed equipment,” Arkush laughs. “We were a group of film maniacs who grew up on the films Roger made. When we each, separately, landed at New World, we had these films in us. We had the predilection for the same things that Roger liked. That is the trick of history.”

Add in Corman’s work with Warhol Factory faces such as Paul Bartel and Mary Woronov (both appeared in Rock ’n’ Roll High School), John Cale’s soundtrack for Demme’s Caged Heat, and Arkush’s then-fondness for all-things Velvets (“I remember seeing Chelsea Girls with Nico”), and Arkush piles connection upon connection upon connection. “Once you start talking about this, it’s like your version of football talk—there’s real passion,” he says of the rabbit hole of Pop Art’s pop culturalism. Calling Corman a “brutal watcher of money” and a “demanding boss” while laughing about those demands, Arkush insists, too, that the producing legend freely gave of his knowledge, and “could see what mistakes you were making two steps before you made them.”

That Arkush and his friends all went to NYU, worked at the Fillmore East, then became part of Corman’s New World Pictures was all the more insidiously interconnected in the very best way—and the perfect subject matter for his co-directorial debut, Hollywood Boulevard. A satire of aspiring actresses, B-movie film studio messiness, and the cheapest way to get there (much of the film was made up of footage from other Corman films, with scores of inside jokes also tied to them), Arkush says that Corman “loved that our first film was so self-aware, that we had the chutzpah to make a movie about ourselves—a roman à clef about a small group of film students and a segment of the art world that nobody knows about.”

“We were a group of film maniacs who grew up on the films Roger made. When we each, separately, landed at New World, we had these films in us.”

Not long after Corman produced Summer School Teachers in 1975 (directed and written by Barbara Peeters, one of many women in the producer’s employ), New World was looking to do yet another high school–themed film. At first, Corman considered doing a movie called “Girls Gym,” with women doing naked gymnastics and little more. Arkush in the meantime had been writing a treatment for “Heavy Metal Kids” about, well, just that. While cooler heads prevailed in regard to exploitative nude gymnastics, an idea for real high school rebellion came up—a rebel yell so savage that its students would blow up their classrooms by film’s end. “I didn’t think that was funny, and besides, we were supposed to be making a comedy,” says Arkush about this literally explosive finale.

“What is rock and roll if not the thing that your parents think will make you become evil? That’s the movie: kids taking over the school with the rebellious spirit of rock and roll.”

Corman was dissuaded from his idea of naked gymnastics but, as it was 1977, the producer’s idea of what was popular leaned toward the mainstream of Thank God It’s Friday and Saturday Night Fever. Corman’s next school film was nearly called “Disco High,” but who blows anything up with a 4/4 beat? Arkush’s lightbulb moment came with his work in (and love of) rock and roll. “What is rock and roll if not the thing that your parents think will make you become evil? That’s the movie: kids taking over the school with the rebellious spirit of rock and roll.”

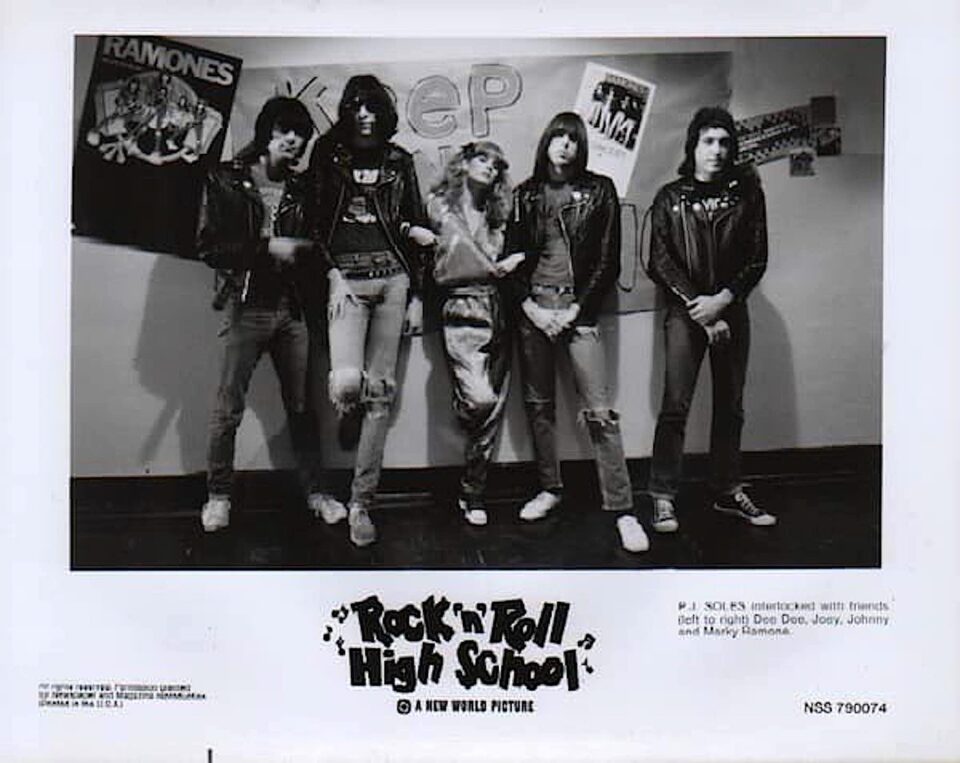

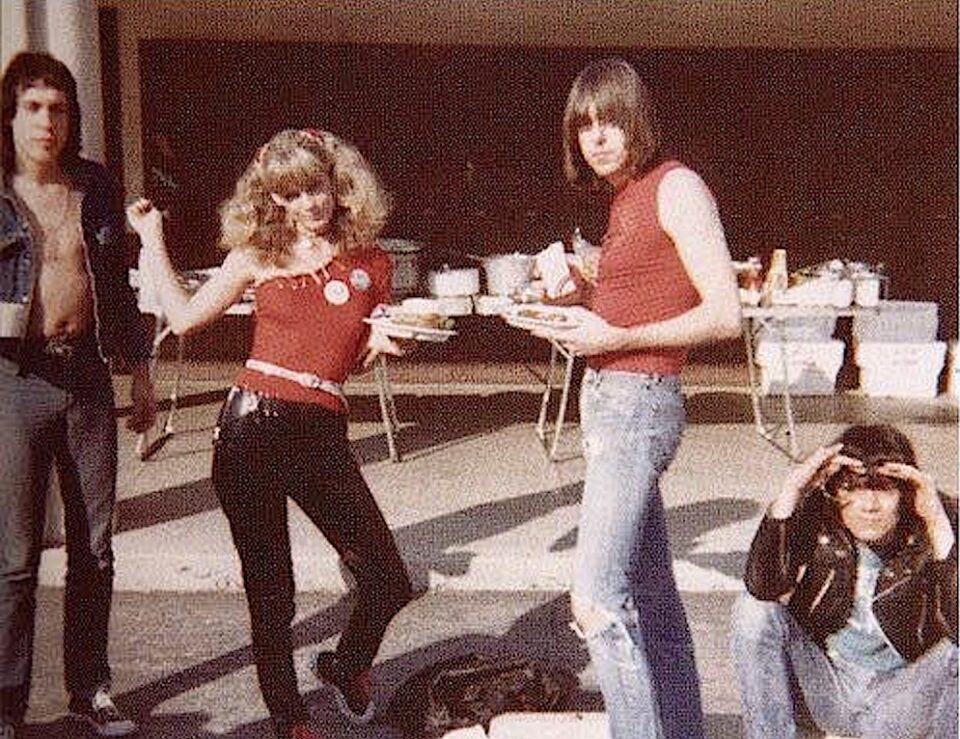

In lieu of scantily clad girls, Arkush wanted to make a film where empowered women ruled the school—“the sort of women who I knew from my time at the Fillmore East, these women who came to every show. Not groupies, just real hardcore fans devoted to music, women who waited three days in line to see The Rolling Stones, young women with agency.” The type of woman that Riff Randall, the lead character of Rock ’n’ Roll High School, might be. “That’s why that movie is a success, and still relevant: It’s about female empowerment,” says Arkush. “Yes, there’s the Ramones, and yes, there’s the unapologetically wacky nature of the movie, but Riff Randall is the character that all the women in the audience identify with. That’s why people returned to see Rock ’n’ Roll High School over and over. That film gives people confidence to talk back to authority.”

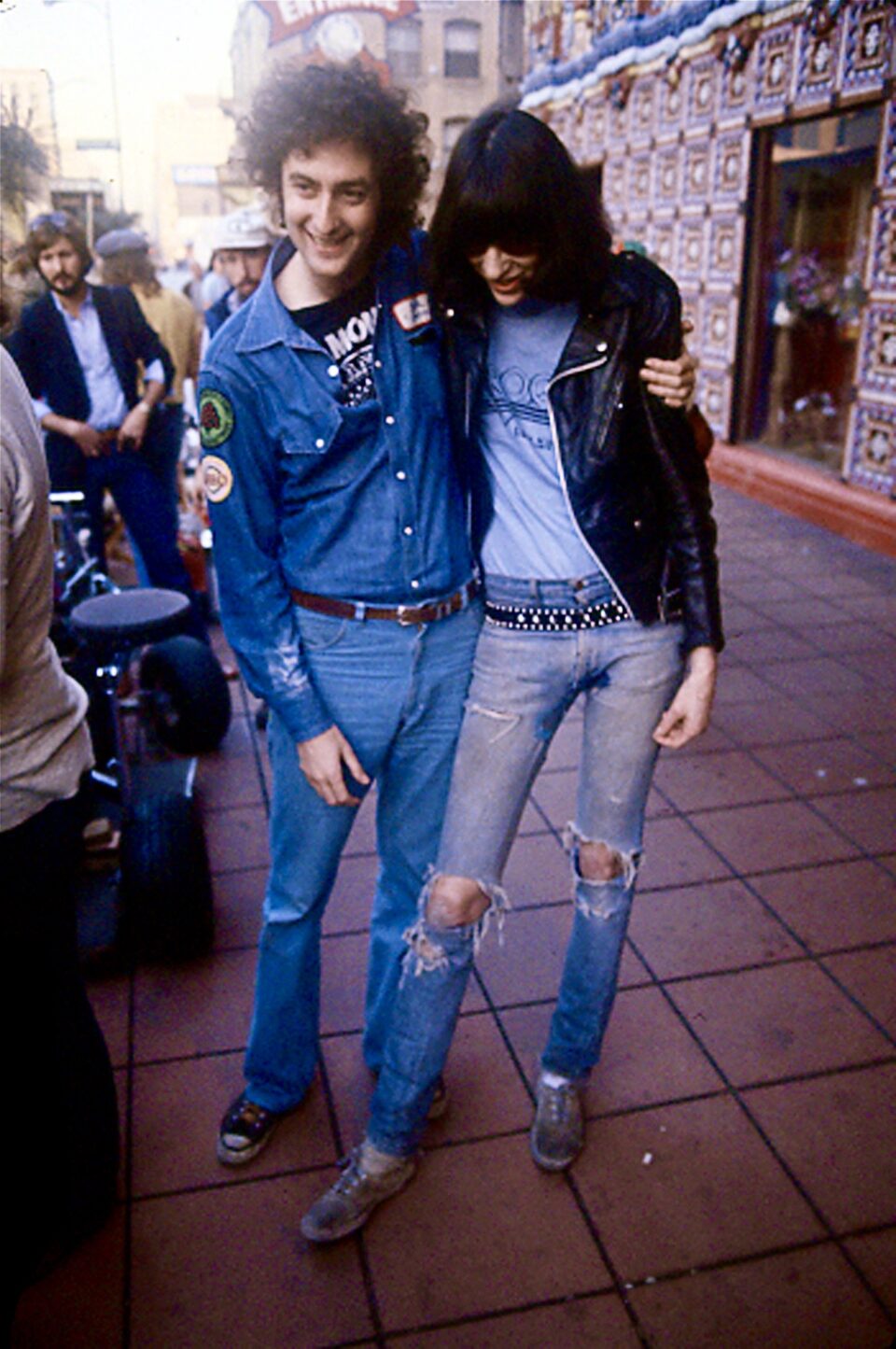

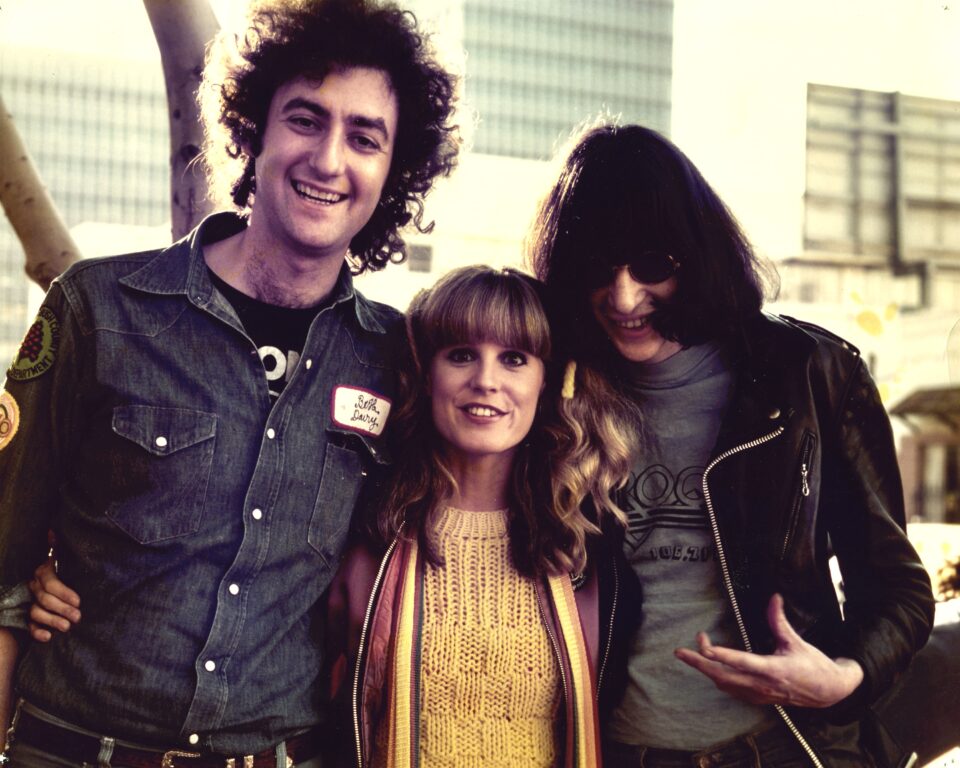

Allan Arkush, PJ Soles and Joey Ramone

Because Corman was a rebel, he realized (at Arkush’s insistence) that its music couldn’t be focused on disco. “Disco then was the music of the middle and the upper class,” says the director. “It wasn’t the sound of rebellion. Remember Pete Townshend destroying his guitar at the end of each set? Metaphorically, that’s the same effect as blowing up a high school at the end of our film.”

“Remember Pete Townshend destroying his guitar at the end of each set? Metaphorically, that’s the same effect as blowing up a high school at the end of our film.”

The last piece in the puzzle of the explosive now-non-disco Corman film was the music at its center: Who would be the band to represent the rebellion of Rock ’n’ Roll High School? While Cheap Trick and Todd Rundgren were part of initial conversations, and Devo and Van Halen were suggested, the Ramones—a band Arkush dug due to its punk rock stance, leather jackets, and sense of humor—prevailed. “When they sang ‘Second verse, same as the first,’ and I heard all of Rocket to Russia, I thought they were the best,” says Arkush. “With all of the exploitative stuff gone, this was now a perfect film. My years with all the bands at the Fillmore East and my love of The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night made it so that when I filmed the Ramones, I wanted it to be slamming. I wanted their concert scenes to pin you back. When Joey sings to Riff in her bedroom, I wanted it to be like that scene in The Girl Can’t Help It—it’s the same scene as Joey Ramone singing ‘I Want You Around.’ And the Ramones sing ‘Do You Wanna Dance?’—that’s my tribute to MGM musicals, although it’s pretty far-fetched.”

Corman’s trust in Allan Arkush—to say nothing of the cinematic pair’s rebellious streak and a sense of female empowerment—is what makes Rock ’n’ Roll High School special still, and the quintessential Roger Corman experience. FL