Ever since her childhood, Nona Hendryx has wanted to be a robot. In accordance with her fandom of TV shows such as The Twilight Zone, and her early adoption of Afrofuturist literary heroes such as Octavia Butler, Hendryx at the very least sought to live a life of alternative, artificial intelligence and virtual realities. Go back to her songwriting for Labelle, the unconventional R&B-rock vocal trio she shared with Sarah Dash and Patti LaBelle. By the time Labelle got to albums such as 1974’s Nightbirds and 1975’s Phoenix, Hendryx’s compositions focused on “Space Children” and “Black Holes in the Sky” in accordance with the trio’s futuristic glam-funk costuming and Saturn-bound soul. Hendryx’s uncategorizable solo albums of the 1980s also made space the place when they weren’t finding room for liberating sexual politics from the norm.

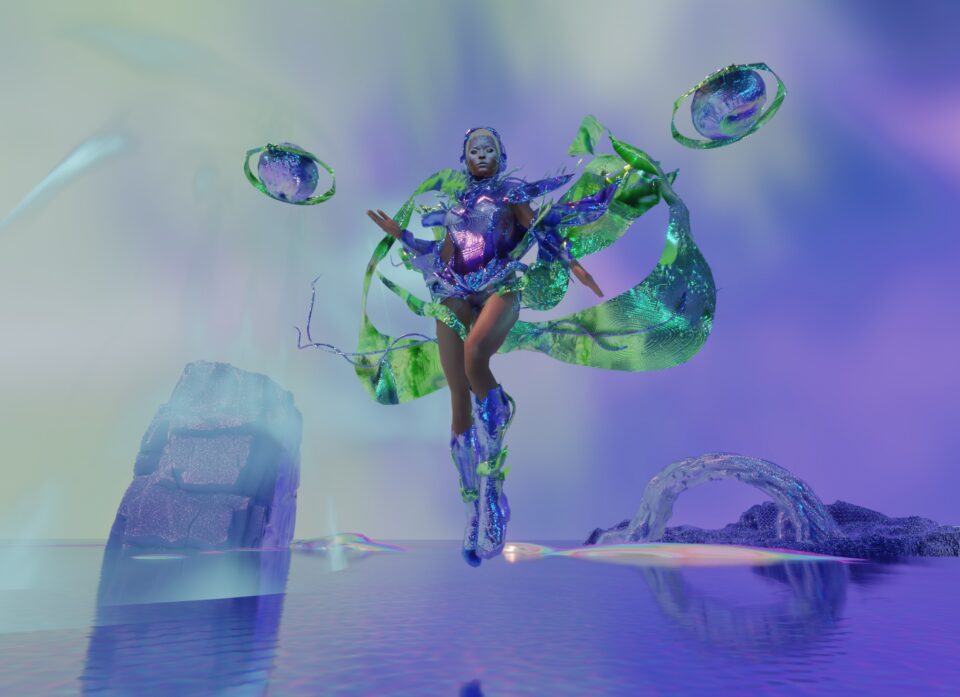

Nothing, however, speaks to Hendryx’s space-and-tech savvy origin story than The Dream Machine Experience: before the before and after the after. Taking over the entirety of NYC’s Lincoln Center campus until the end of June, Hendryx’s Dream reality is often a virtual one, as it presents distinct, colorful segments combining the physical and digital worlds via Afrofuturist art, music, and storytelling with everything from AI-powered humanoid robots to an AR journey guided by Hendryx’s virtual avatar and a proactive stroll through a full-scale VR drama, The Dream Machine, where you can interact with digital George Clintons and Laurie Andersons at play with host Hendryx.

Before the installation and all of its real and surreal components kicked off last week, Hendryx made time to discuss the ins and outs of a lifetime of Afrofuturist ideas and deeds.

Afrofuturism has been part of you since childhood. Can you tell me about what first turned your head about Octavia Butler and Sun Ra?

It goes back even further than that, as I was drawn to television shows such as The Twilight Zone. There was a space-traveling actor named Buster Crabbe who portrayed science fiction heroes such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. Anything that had to do with outer space and science fiction fascinated me, even later with films such as Star Wars and reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. I was captivated by this brand of imagination. Even as a subject in school, I was always interested in science. To be alive long enough that I was able to use computers and its technology to play with and make music…it’s just been a natural progression, an exploration.

Can you recall what first works or songs of your own had the influence of sci-fi as part of their make up?

Some of my early drawings in charcoal had these unknown figures. Some of my early poetry was influenced by authors who were writing about everyday occurrences that became very strange very fast. When I was in Labelle, that’s where I began to have a space to dig into that place—bring those characters to life we could portray on stage in songs such as “The Man in the Trench Coat” and “Cosmic Dancer.” The Afrofuturism that I was exploring really came alive through Labelle. I was looking to express to the physical world what was going on inside my head.

“The Afrofuturism that I was exploring really came alive through Labelle. I was looking to express to the physical world what was going on inside my head.”

Tell me about merging your musical sci-fi conceptualism with that of Labelle’s costume team and designer Larry LeGaspi’s mix of silver suits, feathers, mirrors, and studs.

Larry was the key to it all. Having all kinds of hair attached to silver, or stones attached to metal. Working with Larry allowed us to create this look, this theme. Larry had a great boutique in the East Village, Moonstone, which he turned into a space-scape. The three of us would go to his shop and dream up what we wanted to wear, find out what Larry’s ideas were—it was a true back-and-forth among us. And each of us were genuine individuals and had to consider what Patti liked, what Sarah felt comfortable in, and what metallic silvers suited her. I really loved working with everyone in this group.

You were an early adopter of computer technologies in your solo music and in your way of thinking. Did you see a future that involved AI and virtualism?

Yes. I had longed to be a cyborg since childhood—at least since the 1960s. I believed that once we got into the 2000s, that I would actually be a cyborg. Obviously, the technology is slow [laughs]. I feel as if, however, we’re finally on our way there, what with artificial hearts and limbs. A friend of mine is working on artificial expanding lungs.

I think of your solo albums The Art of Defense and Female Trouble as you making future-forward tracks with Afrikka Bambaataa and Material, of songs that spoke to free sexual politics. Do you think that audiences understood what you were making then?

I think there were some people who understood and came along with me on my own little personal spaceship. They were kindred spirits, maybe. Artists such as Peter Gabriel and Laurie Anderson were onboard. So were George Clinton and Living Colour. As for the broader audience, it took a while to get there. It took seeing Star Wars, the moon landing, and further space travel for the mainstream to see the possibilities, and why an artist would also create in that space.

I was thinking of what The Dream Machine looks and sounds like, and I have to know if William S. Burroughs is any kind of inspiration, as so much of his work focused on the extremes of virtual reality and artificial intelligence, especially in the dream state.

Burroughs meant quite a bit to me, actually. A huge influence. The Dream Machine could have been born out of a William S. Burroughs moment. I’m working on something new, now, that’s a nod to Burroughs, as well.

“I had longed to be a cyborg since childhood—at least since the 1960s. I believed that once we got into the 2000s, that I would actually be a cyborg.”

Let’s talk about the origin story of The Dream Machine as a staged and environmental work—a forum for your ideas—and its many separate spaces. It’s truly epic in scope.

The Dream Machine evolved over time, and only came into view about seven or eight years ago when I was named an ambassador at the Berklee College of Music. They were interested in me working with the voice and ensemble department, to which I agreed—but only if I could also work with the electronic design and production department [laughs]. There, I met kindred spirits such as Dr. Boulanger, and I began to have the freedom to explore ideas of how to integrate music, technology, and visual arts for performance on stage so that they’re not separate.

What makes Lincoln Center’s complex the ideal location for The Dream Machine?

It’s perfect because much of the vision of The Dream Machine centers on the past, the present, and the future. Because Lincoln Center has its own past, the removal of noble people from a community to build that center, it was important to make that story anew and talk about how we could create a future from that. It was important to talk about Afro-future space that’s looking at the past in the present for the future. It was important to have such a large space, especially the atrium, so as to create an Afro-future garden. BINA48’s Afro Future Garden was designed by Mickalene Thomas with interior and set design by Lutfi Janania, and features a humanoid robot powered by AI, which is the only social robot inspired, created, and programmed with mind files from an African-American woman, Bina Rothblatt. That was an amazing opportunity for actors, writers, students, and poets—to be in residence and conversation.

Then we take people on a trip on The Bridge, telling the story of other famous artists such as Robert McFerrin, Bobby’s father, who was one of the first Black opera singers along with Leontyne Price and Marian Anderson. This is an opportunity to share history into the future.

“The vision of The Dream Machine centers on the past, the present, and the future. Because Lincoln Center has its own past, it was important to talk about how we could create a future from that.”

It seems as if you’re attempting to take away a lot of the perceived fears as to what AI and VR might actually be and do.

That is true. It’s important for me to share and have others share how artists go out on a limb to inform and fight misinformation when it comes to AI and its possibilities and dangers. We make what exists, so it is us and not AI, which is dangerous. What we do with what we make is good or not good. Come and be in the garden, engage with the professors and artists, look at ownership and ownership rights, AI rights—and what will these rights be in the future? You’ll be able to talk about these questions without being spoon-fed information about this technology.

What’s your take on the downside of copywriting in an AI universe? What happens if you want to own or control your own work?

I think we’ve gone way past that point [laughs]. I’ve lived through the argument of synthesizers, for instance, and whether that was a legitimate instrument—that it’s not a musician. I say if the genie is out of the bottle, it’s best to get friendly with the genie.

You have a larger-than-life avatar during the Bridge experience, to go with your Cyber Oracle. How close does all this come to what you wanted for yourself during your childhood?

It feels great. There’s an AR poster of The Dream Experience where, if you use your QR code, I burst forth from that background and engage with you. That’s the life I want to live. I can’t be in that space all the time, but I’m making strides. FL